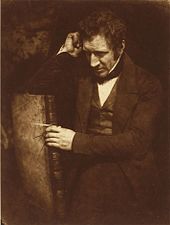

| James Nasmyth | |

|---|---|

Woodburytype print, c.1877 Woodburytype print, c.1877 | |

| Born | 19 August 1808 (1808-08-19) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 7 May 1890 (1890-05-08) (aged 81) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | Heriot-Watt University |

| Known for | Steam hammer Machine tools Locomotives Astronomy Photography |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mechanical engineer Artist Inventor |

| Institutions | Nasmyth, Gaskell and Company,(1836–50) James Nasmyth and Company (1850–56) |

James Hall Nasmyth (sometimes spelled Naesmyth, Nasmith, or Nesmyth) (19 August 1808 – 7 May 1890) was a Scottish engineer, philosopher, artist and inventor famous for his development of the steam hammer. He was the co-founder of Nasmyth, Gaskell and Company manufacturers of machine tools. He retired at the age of 48, and moved to Penshurst, Kent where he developed his hobbies of astronomy and photography.

Early life

Nasmyth was born at 47 York Place, Edinburgh where his father Alexander Nasmyth was a landscape and portrait painter. One of Alexander's hobbies was mechanics and he employed nearly all his spare time in his workshop where he encouraged his youngest son to work with him in all sorts of materials. James was sent to the Royal High School where he had as a friend, Jimmy Patterson, the son of a local iron founder. Being already interested in mechanics he spent much of his time at the foundry and there he gradually learned to work and turn in wood, brass, iron, and steel. In 1820 he left the High School and again made great use of his father's workshop where at the age of 17, he made his first steam engine.

From 1821 to 1826, Nasmyth regularly attended the Edinburgh School of Arts (today Heriot-Watt University, making him one of the first students of the institution). In 1828 he made a complete steam carriage that was capable of running a mile carrying 8 passengers. This accomplishment increased his desire to become a mechanical engineer. He had heard of the fame of Henry Maudslay's workshop and resolved to get employment there; unfortunately his father could not afford to place him as an apprentice at Maudslay's works. Nasmyth therefore decided instead to show Maudslay examples of his skills and produced a complete working model of a high-pressure steam engine, creating the working drawings and constructing the components himself.

Career

In May 1829, Nasmyth visited Maudslay in London, and after showing him his work was engaged as an assistant workman at 10 shillings a week. Unfortunately, Maudslay died two years later, whereupon Nasmyth was taken on by Maudslay's partner as a draughtsman.

When Nasmyth was 23 years old, having saved the sum of £69, he decided to set up in business on his own. He rented a factory flat 130 feet long by 27 feet wide at an old cotton mill on Dale Street, Manchester.

The combination of massive castings and a wooden floor was not an ideal one, and after an accident involving one end of an engine beam crashing through the floor into a glass cutters flat below he soon relocated. He moved to Patricroft, an area of the town of Eccles, Lancashire, where in August 1836, he and his business partner Holbrook Gaskell opened the Bridgewater Foundry, where they traded as Nasmyth, Gaskell and Company. The premises were constructed adjacent to the (then new) Liverpool and Manchester Railway and the Bridgewater Canal.

In March 1838 James was making a journey by coach from Sheffield to York in a snowstorm, when he spied some ironwork furnaces in the distance. The coachman informed him that they were managed by a Mr. Hartop who was one of his customers. He immediately got off the coach and headed for the furnaces through the deep snow. He found Mr. Hartop at his house, and was invited to stay the night and visit the works the next day. That evening he met Hartop's family and was immediately smitten by his 21-year-old daughter, Anne. A decisive man, the next day he told her of his feelings and intentions, which was received "in the best spirit that I could desire." He then communicated the same to her parents, and told them his prospects, and so became betrothed in the same day. They were married two years later, on 16 June 1840 in Wentworth.

Up to 1843, Nasmyth, Gaskell & Co. concentrated on producing a wide range of machine tools in large numbers. By 1856, Nasmyth had built 236 shaping machines.

In 1840 he began to receive orders from the newly opened railways which were beginning to cover the country, for locomotives. His connection with the Great Western Railway whose famous steamship SS Great Western had been so successful in voyages between Bristol and New York, led to him being asked to make some machine tools of unusual size and power which were required for the construction of the engines of their next and bigger ship SS Great Britain.

The steam hammer

In 1837, the Great Western Steam Company was experiencing many problems forging the paddle shaft of the SS Great Britain; when even the largest hammer was tilted to its full height its range was so small that if a really large piece of work were placed on the anvil, the hammer had no room to fall, and in 1838 the company's engineer (Francis Humphries) wrote to Nasmyth: "I find there is not a forge-hammer in England or Scotland powerful enough to forge the paddle-shaft of the engine for the Great Britain! What am I to do?”

Nasmyth thought the matter over and seeing the obvious defects of the tilt-hammer (it delivered every blow with the same force) sketched out his idea for the first steam hammer. He kept his ideas for new devices, mostly in drawings, in a "Scheme Book" which he freely showed to his foreign customers. Nasmyth made a sketch of his steam hammer design dated 24 November 1839, but the immediate need disappeared when the practicality of screw propellers was demonstrated and the Great Britain was converted to that design.

The French engineer François Bourdon came up with the similar idea of what he called a "Pilon" in 1839 and made detailed drawings of his design, which he also showed to all engineers who visited the works at Le Creusot owned by the brothers Adolphe and Eugène Schneider. However, the Schneiders hesitated to build Bourdon's radical new machine. Bourdon and Eugène Schneider visited the Nasmyth works in England in the middle of 1840, where they were shown Nasmyth's sketch. This confirmed the feasibility of the concept to Schneider. In 1840 Bourdon built the first steam hammer in the world at the Schneider & Cie works at Le Creusot. It weighed 2,500 kilograms (5,500 lb) and lifted to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in). The Schneiders patented the design in 1841.

In April 1842 Nasmyth visited France with a view to supplying the French arsenals and dockyards with tools and while he was there took the opportunity to visit the Le Creusot works. On going round the works, he found the steam-hammer at work. By his account, Bourdon took him to the forge department so he might, as he said, "see his own child". Nasmyth said "there it was, in truth–a thumping child of my brain!" Nasmyth patented his design in June 1842 using money borrowed from his sister Anne's husband William Bennett. He built his first steam hammer later that year in his Patricroft foundry. In 1843 a dispute broke out between the two engineers over priority of invention of the steam hammer.

By using the hammer, production costs could be reduced by over 50 percent, while at the same time improving the quality of the forgings produced.

The first hammers were of the free-fall type but they were later modified, given power-assisted fall. Up until then, the invention of Nasmyth's steam-hammer, large forging, such as ships' anchors, had to be made by the "bit-by-bit" process, that is, small pieces were forged separately and finally welded together. A key feature of his machine was that the operator controlled the force of each blow. He enjoyed showing off its capability by demonstrating how it could first break an egg placed in a wine glass, without breaking the glass, which was followed by a full-force blow which shook the building. Its advantages soon became so obvious that before long Nasmyth hammers were to be found in all the large workshops all over the country.

An original Nasmyth hammer now stands facing Nasmyth's Patricroft foundry buildings (now a 'business park'). A larger Nasmyth & Wilson steam hammer stands in the campus of the University of Bolton.

Nasmyth subsequently applied the principle of his steam hammer to a pile-driving machine which he invented in 1843. His first full scale machine used a four-ton hammer-block, and a rate of eighty blows per minute. The pile driver was first demonstrated in a contest with a team using the conventional method at Devonport on 3 July 1845. He drove a pile 70 feet long and 18 inches squared in four and a half minutes, while the conventional method required twelve hours. This was a great success, and many orders for his pile driver resulted. It was used for many large scale constructions all over the world in the next few years, such as the High Level Bridge at Newcastle upon Tyne and the Nile barrage at Aswan, Egypt (Aswan Low Dam).

By 1856 a total of 490 hammers had been produced which were sold across Europe to Russia, India and even Australia, and accounted for 40% of James Nasmyth and Company's revenues.

Other inventions

Apart from the steam hammer, Nasmyth created several other important machine tools, including the shaper, an adaptation of the planer which is still used in tool and die making. Another innovation was a hydraulic press which used water pressure to force tight-fitting machine parts together. All of these machines became popular in manufacturing, and all are still in use in modified form.

Nasmyth was also one of the first toolmakers to offer a standardised range of machine tools; before this, manufacturers constructed tools according to individual clients' specifications with little regard to standardisation, which caused compatibility problems. Nasmyth was arguably the last of the early pioneers of the machine tool industry.

Among Nasmyth's other inventions, most of which he never patented, were a means of transmitting rotary motion by means of a flexible shaft made of coiled wire, a machine for cutting key grooves, self-adjusting bearings, and the screw ladle for moving molten metal which could safely and efficiently be handled by two men instead of the six previously required. Nasmyth's idea of a steam ram for naval warfare was never put into production.

In 1844 he, together with engineer Charles May, patented the first Vacuum brake.

Although milling machines were no longer novel by 1830, an example built by Nasmyth around that time stands out for its prescience. It was tooled to mill the six sides of a hex nut that was mounted in a six-way indexing fixture.

He also worked on a project for the conversion of iron which was not dis-similar to that which was eventually patented by Henry Bessemer. A reluctant patentor, and in this instance still working through some problems in his method, Nasmyth abandoned the project after hearing of Bessemer's ideas in 1856. Bessemer, however, acknowledged the efforts of Nasmyth by offering him a one-third share of the value of his patent for the eponymous Bessemer process. Nasmyth turned it down as he had decided to retire.

Later life

Nasmyth retired from business in 1856 when he was 48 years old, as he said "I have now enough of this world's goods: let younger men have their chance". He settled down near Penshurst, Kent, where he renamed his retirement home "Hammerfield" and happily pursued his various hobbies including astronomy. He built his own 20-inch reflecting telescope, in the process inventing the Nasmyth focus, and made detailed observations of the Moon. He co-wrote The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite (1874) with James Carpenter (1840–1899). This book contains an interesting series of "lunar" photographs: because photography was not yet advanced enough to take pictures at very high magnification directly of the Moon itself, Nasmyth built plaster relief scale models based on his visual observations of the Moon and then photographed the models under electric illumination, replicating the shadows of the topographic contours he observed on the Moon. A crater on the Moon is named after him.

He was happily married to his wife Anne, from Woodburn, Yorkshire, for 50 years, until his death. They had no children.

They are buried in the north section of the Dean Cemetery in western Edinburgh. The huge memorial stands at the east end of the main east–west path, with the path dividing around it. The monument holds a well-carved model of his steam hammer. James' mother, Barbara Foulis (1765-1848) is buried with them. The monument also stands as a memorial to his brother, Patrick Nasmyth (1787-1831)

Recognition

In memory of his renowned contribution to the discipline of mechanical engineering, the Department of Mechanical Engineering building at Heriot-Watt University, in his birthplace of Edinburgh, is called the James Nasmyth Building.

See also

References

Citations

- Nasmyth & Smiles 1883.

- MussonRobinson 1969, p. 491.

- ^ Boutany 1885, p. 59.

- Chomienne 1888, p. 254.

- François BOURDON: Archives Côte d’Or.

- Smiles 2015, Ch. XV.

- Nasmyth & Smiles 1883, p. 259.

- Nasmyth steam hammer.

- The Repertory of Patent Inventions: And Other Discoveries and Improvements in Arts, Manufactures, and Agriculture; Being a Continuation, on an Enlarged Plan, of the Repertory of Arts & Manufactures. proprietors. 1845.

- Woodbury 1972, p. 24-26.

- Lord 1945, p. 164.

Sources

- Boutany (1885). "Who Invented the Steam Hammer?". Engineering News-record. McGraw-Hill.

- Chomienne, C. (1888). "Notes on Steam Hammers". Railway Locomotives and Cars. Simmons-Boardman.

- "François BOURDON". Archives Départementales numérisées de la Côte d’Or. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Lord, W. M. (1945). "The Development of the Bessemer Process in Lancashire, 1856–1900". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 25 (1): 163–180. doi:10.1179/tns.1945.017. ISSN 0372-0187.

- Musson, Albert Edward; Robinson, Eric (1969). Science and technology in the Industrial Revolution. Manchester University Press. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-7190-0370-7.

- Nasmyth, James; Smiles, Samuel (1883). James Nasmyth Engineer: An Autobiography. London: John Murray.

- Smiles, Samuel (2015). "Ch.XV". Industrial Biography - Iron Workers and Tool Makers. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4733-7118-7.

- "Nasmyth steam hammer, c.1850". The Science Museum. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Woodbury, Robert S. (1972) . History of the Milling Machine. In Studies in the History of Machine Tools. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, and London, England: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73033-4. LCCN 72006354. First published alone as a monograph in 1960.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

Further reading

- Cantrell, J. A. (2006). "James Nasmyth and the Bridgewater Foundry: Partners and Partnerships". Business History. 23 (3): 346–358. doi:10.1080/00076798100000064. ISSN 0007-6791.

- Dickinson, R. (1956). "James Nasmyth and the Liverpool Iron Trade" (PDF). Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Historical Society. 108: 83–104.

- Musson, A. E. (1957). "James Nasmyth and the Early Growth of Mechanical Engineering". The Economic History Review. 10 (1): 121–127. doi:10.2307/2600067. ISSN 0013-0117. JSTOR 2600067.

External links

Works by or about James Nasmyth at Wikisource

Works by or about James Nasmyth at Wikisource Quotations related to James Nasmyth at Wikiquote

Quotations related to James Nasmyth at Wikiquote- Works by James Nasmyth at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Nasmyth at the Internet Archive

- Bibliomania: Full text of autobiography

- 1808 births

- 1890 deaths

- 19th-century Scottish businesspeople

- Scottish company founders

- Alumni of Heriot-Watt University

- Foundrymen

- Hydraulic engineers

- Machine tool builders

- Mechanical engineers

- People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh

- Engineers from Edinburgh

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- People of the Victorian era

- Scottish engineers

- Scottish inventors

- Scottish mechanical engineers