| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine The classical Carnot heat engine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branches | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Laws | |||||||||||||||||||||

Systems

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

System propertiesNote: Conjugate variables in italics

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Material properties

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Equations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potentials | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientists | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal empirical observation concerning heat and energy interconversions. A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spontaneously from hotter to colder regions of matter (or 'downhill' in terms of the temperature gradient). Another statement is: "Not all heat can be converted into work in a cyclic process."

The second law of thermodynamics establishes the concept of entropy as a physical property of a thermodynamic system. It predicts whether processes are forbidden despite obeying the requirement of conservation of energy as expressed in the first law of thermodynamics and provides necessary criteria for spontaneous processes. For example, the first law allows the process of a cup falling off a table and breaking on the floor, as well as allowing the reverse process of the cup fragments coming back together and 'jumping' back onto the table, while the second law allows the former and denies the latter. The second law may be formulated by the observation that the entropy of isolated systems left to spontaneous evolution cannot decrease, as they always tend toward a state of thermodynamic equilibrium where the entropy is highest at the given internal energy. An increase in the combined entropy of system and surroundings accounts for the irreversibility of natural processes, often referred to in the concept of the arrow of time.

Historically, the second law was an empirical finding that was accepted as an axiom of thermodynamic theory. Statistical mechanics provides a microscopic explanation of the law in terms of probability distributions of the states of large assemblies of atoms or molecules. The second law has been expressed in many ways. Its first formulation, which preceded the proper definition of entropy and was based on caloric theory, is Carnot's theorem, formulated by the French scientist Sadi Carnot, who in 1824 showed that the efficiency of conversion of heat to work in a heat engine has an upper limit. The first rigorous definition of the second law based on the concept of entropy came from German scientist Rudolf Clausius in the 1850s and included his statement that heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

The second law of thermodynamics allows the definition of the concept of thermodynamic temperature, but this has been formally delegated to the zeroth law of thermodynamics.

Introduction

The first law of thermodynamics provides the definition of the internal energy of a thermodynamic system, and expresses its change for a closed system in terms of work and heat. It can be linked to the law of conservation of energy. Conceptually, the first law describes the fundamental principle that systems do not consume or 'use up' energy, that energy is neither created nor destroyed, but is simply converted from one form to another.

The second law is concerned with the direction of natural processes. It asserts that a natural process runs only in one sense, and is not reversible. That is, the state of a natural system itself can be reversed, but not without increasing the entropy of the system's surroundings, that is, both the state of the system plus the state of its surroundings cannot be together, fully reversed, without implying the destruction of entropy.

For example, when a path for conduction or radiation is made available, heat always flows spontaneously from a hotter to a colder body. Such phenomena are accounted for in terms of entropy change. A heat pump can reverse this heat flow, but the reversal process and the original process, both cause entropy production, thereby increasing the entropy of the system's surroundings. If an isolated system containing distinct subsystems is held initially in internal thermodynamic equilibrium by internal partitioning by impermeable walls between the subsystems, and then some operation makes the walls more permeable, then the system spontaneously evolves to reach a final new internal thermodynamic equilibrium, and its total entropy, , increases.

In a reversible or quasi-static, idealized process of transfer of energy as heat to a closed thermodynamic system of interest, (which allows the entry or exit of energy – but not transfer of matter), from an auxiliary thermodynamic system, an infinitesimal increment () in the entropy of the system of interest is defined to result from an infinitesimal transfer of heat () to the system of interest, divided by the common thermodynamic temperature of the system of interest and the auxiliary thermodynamic system:

Different notations are used for an infinitesimal amount of heat and infinitesimal change of entropy because entropy is a function of state, while heat, like work, is not.

For an actually possible infinitesimal process without exchange of mass with the surroundings, the second law requires that the increment in system entropy fulfills the inequality

This is because a general process for this case (no mass exchange between the system and its surroundings) may include work being done on the system by its surroundings, which can have frictional or viscous effects inside the system, because a chemical reaction may be in progress, or because heat transfer actually occurs only irreversibly, driven by a finite difference between the system temperature (T) and the temperature of the surroundings (Tsurr).

The equality still applies for pure heat flow (only heat flow, no change in chemical composition and mass),

which is the basis of the accurate determination of the absolute entropy of pure substances from measured heat capacity curves and entropy changes at phase transitions, i.e. by calorimetry.

Introducing a set of internal variables to describe the deviation of a thermodynamic system from a chemical equilibrium state in physical equilibrium (with the required well-defined uniform pressure P and temperature T), one can record the equality

The second term represents work of internal variables that can be perturbed by external influences, but the system cannot perform any positive work via internal variables. This statement introduces the impossibility of the reversion of evolution of the thermodynamic system in time and can be considered as a formulation of the second principle of thermodynamics – the formulation, which is, of course, equivalent to the formulation of the principle in terms of entropy.

The zeroth law of thermodynamics in its usual short statement allows recognition that two bodies in a relation of thermal equilibrium have the same temperature, especially that a test body has the same temperature as a reference thermometric body. For a body in thermal equilibrium with another, there are indefinitely many empirical temperature scales, in general respectively depending on the properties of a particular reference thermometric body. The second law allows a distinguished temperature scale, which defines an absolute, thermodynamic temperature, independent of the properties of any particular reference thermometric body.

Various statements of the law

The second law of thermodynamics may be expressed in many specific ways, the most prominent classical statements being the statement by Rudolf Clausius (1854), the statement by Lord Kelvin (1851), and the statement in axiomatic thermodynamics by Constantin Carathéodory (1909). These statements cast the law in general physical terms citing the impossibility of certain processes. The Clausius and the Kelvin statements have been shown to be equivalent.

Carnot's principle

The historical origin of the second law of thermodynamics was in Sadi Carnot's theoretical analysis of the flow of heat in steam engines (1824). The centerpiece of that analysis, now known as a Carnot engine, is an ideal heat engine fictively operated in the limiting mode of extreme slowness known as quasi-static, so that the heat and work transfers are between subsystems that are always in their own internal states of thermodynamic equilibrium. It represents the theoretical maximum efficiency of a heat engine operating between any two given thermal or heat reservoirs at different temperatures. Carnot's principle was recognized by Carnot at a time when the caloric theory represented the dominant understanding of the nature of heat, before the recognition of the first law of thermodynamics, and before the mathematical expression of the concept of entropy. Interpreted in the light of the first law, Carnot's analysis is physically equivalent to the second law of thermodynamics, and remains valid today. Some samples from his book are:

- ...wherever there exists a difference of temperature, motive power can be produced.

- The production of motive power is then due in steam engines not to an actual consumption of caloric, but to its transportation from a warm body to a cold body ...

- The motive power of heat is independent of the agents employed to realize it; its quantity is fixed solely by the temperatures of the bodies between which is effected, finally, the transfer of caloric.

In modern terms, Carnot's principle may be stated more precisely:

- The efficiency of a quasi-static or reversible Carnot cycle depends only on the temperatures of the two heat reservoirs, and is the same, whatever the working substance. A Carnot engine operated in this way is the most efficient possible heat engine using those two temperatures.

Clausius statement

The German scientist Rudolf Clausius laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics in 1850 by examining the relation between heat transfer and work. His formulation of the second law, which was published in German in 1854, is known as the Clausius statement:

Heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

The statement by Clausius uses the concept of 'passage of heat'. As is usual in thermodynamic discussions, this means 'net transfer of energy as heat', and does not refer to contributory transfers one way and the other.

Heat cannot spontaneously flow from cold regions to hot regions without external work being performed on the system, which is evident from ordinary experience of refrigeration, for example. In a refrigerator, heat is transferred from cold to hot, but only when forced by an external agent, the refrigeration system.

Kelvin statements

Lord Kelvin expressed the second law in several wordings.

- It is impossible for a self-acting machine, unaided by any external agency, to convey heat from one body to another at a higher temperature.

- It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects.

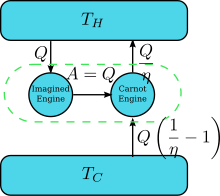

Equivalence of the Clausius and the Kelvin statements

Suppose there is an engine violating the Kelvin statement: i.e., one that drains heat and converts it completely into work (the drained heat is fully converted to work) in a cyclic fashion without any other result. Now pair it with a reversed Carnot engine as shown by the right figure. The efficiency of a normal heat engine is η and so the efficiency of the reversed heat engine is 1/η. The net and sole effect of the combined pair of engines is to transfer heat from the cooler reservoir to the hotter one, which violates the Clausius statement. This is a consequence of the first law of thermodynamics, as for the total system's energy to remain the same; , so therefore , where (1) the sign convention of heat is used in which heat entering into (leaving from) an engine is positive (negative) and (2) is obtained by the definition of efficiency of the engine when the engine operation is not reversed. Thus a violation of the Kelvin statement implies a violation of the Clausius statement, i.e. the Clausius statement implies the Kelvin statement. We can prove in a similar manner that the Kelvin statement implies the Clausius statement, and hence the two are equivalent.

Planck's proposition

Planck offered the following proposition as derived directly from experience. This is sometimes regarded as his statement of the second law, but he regarded it as a starting point for the derivation of the second law.

- It is impossible to construct an engine which will work in a complete cycle, and produce no effect except the production of work and cooling of a heat reservoir.

Relation between Kelvin's statement and Planck's proposition

It is almost customary in textbooks to speak of the "Kelvin–Planck statement" of the law, as for example in the text by ter Haar and Wergeland. This version, also known as the heat engine statement, of the second law states that

- It is impossible to devise a cyclically operating device, the sole effect of which is to absorb energy in the form of heat from a single thermal reservoir and to deliver an equivalent amount of work.

Planck's statement

Max Planck stated the second law as follows.

- Every process occurring in nature proceeds in the sense in which the sum of the entropies of all bodies taking part in the process is increased. In the limit, i.e. for reversible processes, the sum of the entropies remains unchanged.

Rather like Planck's statement is that of George Uhlenbeck and G. W. Ford for irreversible phenomena.

- ... in an irreversible or spontaneous change from one equilibrium state to another (as for example the equalization of temperature of two bodies A and B, when brought in contact) the entropy always increases.

Principle of Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory formulated thermodynamics on a purely mathematical axiomatic foundation. His statement of the second law is known as the Principle of Carathéodory, which may be formulated as follows:

In every neighborhood of any state S of an adiabatically enclosed system there are states inaccessible from S.

With this formulation, he described the concept of adiabatic accessibility for the first time and provided the foundation for a new subfield of classical thermodynamics, often called geometrical thermodynamics. It follows from Carathéodory's principle that quantity of energy quasi-statically transferred as heat is a holonomic process function, in other words, .

Though it is almost customary in textbooks to say that Carathéodory's principle expresses the second law and to treat it as equivalent to the Clausius or to the Kelvin-Planck statements, such is not the case. To get all the content of the second law, Carathéodory's principle needs to be supplemented by Planck's principle, that isochoric work always increases the internal energy of a closed system that was initially in its own internal thermodynamic equilibrium.

Planck's principle

In 1926, Max Planck wrote an important paper on the basics of thermodynamics. He indicated the principle

- The internal energy of a closed system is increased by an adiabatic process, throughout the duration of which, the volume of the system remains constant.

This formulation does not mention heat and does not mention temperature, nor even entropy, and does not necessarily implicitly rely on those concepts, but it implies the content of the second law. A closely related statement is that "Frictional pressure never does positive work." Planck wrote: "The production of heat by friction is irreversible."

Not mentioning entropy, this principle of Planck is stated in physical terms. It is very closely related to the Kelvin statement given just above. It is relevant that for a system at constant volume and mole numbers, the entropy is a monotonic function of the internal energy. Nevertheless, this principle of Planck is not actually Planck's preferred statement of the second law, which is quoted above, in a previous sub-section of the present section of this present article, and relies on the concept of entropy.

A statement that in a sense is complementary to Planck's principle is made by Claus Borgnakke and Richard E. Sonntag. They do not offer it as a full statement of the second law:

- ... there is only one way in which the entropy of a system can be decreased, and that is to transfer heat from the system.

Differing from Planck's just foregoing principle, this one is explicitly in terms of entropy change. Removal of matter from a system can also decrease its entropy.

Relating the second law to the definition of temperature

The second law has been shown to be equivalent to the internal energy U defined as a convex function of the other extensive properties of the system. That is, when a system is described by stating its internal energy U, an extensive variable, as a function of its entropy S, volume V, and mol number N, i.e. U = U (S, V, N), then the temperature is equal to the partial derivative of the internal energy with respect to the entropy (essentially equivalent to the first TdS equation for V and N held constant):

Second law statements, such as the Clausius inequality, involving radiative fluxes

The Clausius inequality, as well as some other statements of the second law, must be re-stated to have general applicability for all forms of heat transfer, i.e. scenarios involving radiative fluxes. For example, the integrand (đQ/T) of the Clausius expression applies to heat conduction and convection, and the case of ideal infinitesimal blackbody radiation (BR) transfer, but does not apply to most radiative transfer scenarios and in some cases has no physical meaning whatsoever. Consequently, the Clausius inequality was re-stated so that it is applicable to cycles with processes involving any form of heat transfer. The entropy transfer with radiative fluxes () is taken separately from that due to heat transfer by conduction and convection (), where the temperature is evaluated at the system boundary where the heat transfer occurs. The modified Clausius inequality, for all heat transfer scenarios, can then be expressed as,

In a nutshell, the Clausius inequality is saying that when a cycle is completed, the change in the state property S will be zero, so the entropy that was produced during the cycle must have transferred out of the system by heat transfer. The (or đ) indicates a path dependent integration.

Due to the inherent emission of radiation from all matter, most entropy flux calculations involve incident, reflected and emitted radiative fluxes. The energy and entropy of unpolarized blackbody thermal radiation, is calculated using the spectral energy and entropy radiance expressions derived by Max Planck using equilibrium statistical mechanics, where c is the speed of light, k is the Boltzmann constant, h is the Planck constant, ν is frequency, and the quantities Kv and Lv are the energy and entropy fluxes per unit frequency, area, and solid angle. In deriving this blackbody spectral entropy radiance, with the goal of deriving the blackbody energy formula, Planck postulated that the energy of a photon was quantized (partly to simplify the mathematics), thereby starting quantum theory.

A non-equilibrium statistical mechanics approach has also been used to obtain the same result as Planck, indicating it has wider significance and represents a non-equilibrium entropy. A plot of Kv versus frequency (v) for various values of temperature (T) gives a family of blackbody radiation energy spectra, and likewise for the entropy spectra. For non-blackbody radiation (NBR) emission fluxes, the spectral entropy radiance Lv is found by substituting Kv spectral energy radiance data into the Lv expression (noting that emitted and reflected entropy fluxes are, in general, not independent). For the emission of NBR, including graybody radiation (GR), the resultant emitted entropy flux, or radiance L, has a higher ratio of entropy-to-energy (L/K), than that of BR. That is, the entropy flux of NBR emission is farther removed from the conduction and convection q/T result, than that for BR emission. This observation is consistent with Max Planck's blackbody radiation energy and entropy formulas and is consistent with the fact that blackbody radiation emission represents the maximum emission of entropy for all materials with the same temperature, as well as the maximum entropy emission for all radiation with the same energy radiance.

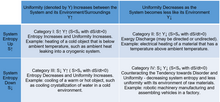

Generalized conceptual statement of the second law principle

Second law analysis is valuable in scientific and engineering analysis in that it provides a number of benefits over energy analysis alone, including the basis for determining energy quality (exergy content), understanding fundamental physical phenomena, and improving performance evaluation and optimization. As a result, a conceptual statement of the principle is very useful in engineering analysis. Thermodynamic systems can be categorized by the four combinations of either entropy (S) up or down, and uniformity (Y) – between system and its environment – up or down. This 'special' category of processes, category IV, is characterized by movement in the direction of low disorder and low uniformity, counteracting the second law tendency towards uniformity and disorder.

The second law can be conceptually stated as follows: Matter and energy have the tendency to reach a state of uniformity or internal and external equilibrium, a state of maximum disorder (entropy). Real non-equilibrium processes always produce entropy, causing increased disorder in the universe, while idealized reversible processes produce no entropy and no process is known to exist that destroys entropy. The tendency of a system to approach uniformity may be counteracted, and the system may become more ordered or complex, by the combination of two things, a work or exergy source and some form of instruction or intelligence. Where 'exergy' is the thermal, mechanical, electric or chemical work potential of an energy source or flow, and 'instruction or intelligence', although subjective, is in the context of the set of category IV processes.

Consider a category IV example of robotic manufacturing and assembly of vehicles in a factory. The robotic machinery requires electrical work input and instructions, but when completed, the manufactured products have less uniformity with their surroundings, or more complexity (higher order) relative to the raw materials they were made from. Thus, system entropy or disorder decreases while the tendency towards uniformity between the system and its environment is counteracted. In this example, the instructions, as well as the source of work may be internal or external to the system, and they may or may not cross the system boundary. To illustrate, the instructions may be pre-coded and the electrical work may be stored in an energy storage system on-site. Alternatively, the control of the machinery may be by remote operation over a communications network, while the electric work is supplied to the factory from the local electric grid. In addition, humans may directly play, in whole or in part, the role that the robotic machinery plays in manufacturing. In this case, instructions may be involved, but intelligence is either directly responsible, or indirectly responsible, for the direction or application of work in such a way as to counteract the tendency towards disorder and uniformity.

There are also situations where the entropy spontaneously decreases by means of energy and entropy transfer. When thermodynamic constraints are not present, spontaneously energy or mass, as well as accompanying entropy, may be transferred out of a system in a progress to reach external equilibrium or uniformity in intensive properties of the system with its surroundings. This occurs spontaneously because the energy or mass transferred from the system to its surroundings results in a higher entropy in the surroundings, that is, it results in higher overall entropy of the system plus its surroundings. Note that this transfer of entropy requires dis-equilibrium in properties, such as a temperature difference. One example of this is the cooling crystallization of water that can occur when the system's surroundings are below freezing temperatures. Unconstrained heat transfer can spontaneously occur, leading to water molecules freezing into a crystallized structure of reduced disorder (sticking together in a certain order due to molecular attraction). The entropy of the system decreases, but the system approaches uniformity with its surroundings (category III).

On the other hand, consider the refrigeration of water in a warm environment. Due to refrigeration, as heat is extracted from the water, the temperature and entropy of the water decreases, as the system moves further away from uniformity with its warm surroundings or environment (category IV). The main point, take-away, is that refrigeration not only requires a source of work, it requires designed equipment, as well as pre-coded or direct operational intelligence or instructions to achieve the desired refrigeration effect.

Corollaries

Perpetual motion of the second kind

Main article: Perpetual motionBefore the establishment of the second law, many people who were interested in inventing a perpetual motion machine had tried to circumvent the restrictions of first law of thermodynamics by extracting the massive internal energy of the environment as the power of the machine. Such a machine is called a "perpetual motion machine of the second kind". The second law declared the impossibility of such machines.

Carnot's theorem

Carnot's theorem (1824) is a principle that limits the maximum efficiency for any possible engine. The efficiency solely depends on the temperature difference between the hot and cold thermal reservoirs. Carnot's theorem states:

- All irreversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are less efficient than a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs.

- All reversible heat engines between two heat reservoirs are equally efficient with a Carnot engine operating between the same reservoirs.

In his ideal model, the heat of caloric converted into work could be reinstated by reversing the motion of the cycle, a concept subsequently known as thermodynamic reversibility. Carnot, however, further postulated that some caloric is lost, not being converted to mechanical work. Hence, no real heat engine could realize the Carnot cycle's reversibility and was condemned to be less efficient.

Though formulated in terms of caloric (see the obsolete caloric theory), rather than entropy, this was an early insight into the second law.

Clausius inequality

The Clausius theorem (1854) states that in a cyclic process

The equality holds in the reversible case and the strict inequality holds in the irreversible case, with Tsurr as the temperature of the heat bath (surroundings) here. The reversible case is used to introduce the state function entropy. This is because in cyclic processes the variation of a state function is zero from state functionality.

Thermodynamic temperature

Main article: Thermodynamic temperatureFor an arbitrary heat engine, the efficiency is:

| (1) |

where Wn is the net work done by the engine per cycle, qH > 0 is the heat added to the engine from a hot reservoir, and qC = −|qC| < 0 is waste heat given off to a cold reservoir from the engine. Thus the efficiency depends only on the ratio |qC| / |qH|.

Carnot's theorem states that all reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient. Thus, any reversible heat engine operating between temperatures TH and TC must have the same efficiency, that is to say, the efficiency is a function of temperatures only:

| (2) |

In addition, a reversible heat engine operating between temperatures T1 and T3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between T1 and another (intermediate) temperature T2, and the second between T2 and T3, where T1 > T2 > T3. This is because, if a part of the two cycle engine is hidden such that it is recognized as an engine between the reservoirs at the temperatures T1 and T3, then the efficiency of this engine must be same to the other engine at the same reservoirs. If we choose engines such that work done by the one cycle engine and the two cycle engine are same, then the efficiency of each heat engine is written as the below.

- ,

- ,

- .

Here, the engine 1 is the one cycle engine, and the engines 2 and 3 make the two cycle engine where there is the intermediate reservoir at T2. We also have used the fact that the heat passes through the intermediate thermal reservoir at without losing its energy. (I.e., is not lost during its passage through the reservoir at .) This fact can be proved by the following.

In order to have the consistency in the last equation, the heat flown from the engine 2 to the intermediate reservoir must be equal to the heat flown out from the reservoir to the engine 3.

Then

Now consider the case where is a fixed reference temperature: the temperature of the triple point of water as 273.16 K; . Then for any T2 and T3,

Therefore, if thermodynamic temperature T* is defined by

then the function f, viewed as a function of thermodynamic temperatures, is simply

and the reference temperature T1* = 273.16 K × f(T1,T1) = 273.16 K. (Any reference temperature and any positive numerical value could be used – the choice here corresponds to the Kelvin scale.)

Entropy

Main article: Entropy (classical thermodynamics)According to the Clausius equality, for a reversible process

That means the line integral is path independent for reversible processes.

So we can define a state function S called entropy, which for a reversible process or for pure heat transfer satisfies

With this we can only obtain the difference of entropy by integrating the above formula. To obtain the absolute value, we need the third law of thermodynamics, which states that S = 0 at absolute zero for perfect crystals.

For any irreversible process, since entropy is a state function, we can always connect the initial and terminal states with an imaginary reversible process and integrating on that path to calculate the difference in entropy.

Now reverse the reversible process and combine it with the said irreversible process. Applying the Clausius inequality on this loop, with Tsurr as the temperature of the surroundings,

Thus,

where the equality holds if the transformation is reversible. If the process is an adiabatic process, then , so .

Energy, available useful work

See also: ExergyAn important and revealing idealized special case is to consider applying the second law to the scenario of an isolated system (called the total system or universe), made up of two parts: a sub-system of interest, and the sub-system's surroundings. These surroundings are imagined to be so large that they can be considered as an unlimited heat reservoir at temperature TR and pressure PR – so that no matter how much heat is transferred to (or from) the sub-system, the temperature of the surroundings will remain TR; and no matter how much the volume of the sub-system expands (or contracts), the pressure of the surroundings will remain PR.

Whatever changes to dS and dSR occur in the entropies of the sub-system and the surroundings individually, the entropy Stot of the isolated total system must not decrease according to the second law of thermodynamics:

According to the first law of thermodynamics, the change dU in the internal energy of the sub-system is the sum of the heat δq added to the sub-system, minus any work δw done by the sub-system, plus any net chemical energy entering the sub-system d ΣμiRNi, so that:

where μiR are the chemical potentials of chemical species in the external surroundings.

Now the heat leaving the reservoir and entering the sub-system is

where we have first used the definition of entropy in classical thermodynamics (alternatively, in statistical thermodynamics, the relation between entropy change, temperature and absorbed heat can be derived); and then the second law inequality from above.

It therefore follows that any net work δw done by the sub-system must obey

It is useful to separate the work δw done by the subsystem into the useful work δwu that can be done by the sub-system, over and beyond the work pR dV done merely by the sub-system expanding against the surrounding external pressure, giving the following relation for the useful work (exergy) that can be done:

It is convenient to define the right-hand-side as the exact derivative of a thermodynamic potential, called the availability or exergy E of the subsystem,

The second law therefore implies that for any process which can be considered as divided simply into a subsystem, and an unlimited temperature and pressure reservoir with which it is in contact,

i.e. the change in the subsystem's exergy plus the useful work done by the subsystem (or, the change in the subsystem's exergy less any work, additional to that done by the pressure reservoir, done on the system) must be less than or equal to zero.

In sum, if a proper infinite-reservoir-like reference state is chosen as the system surroundings in the real world, then the second law predicts a decrease in E for an irreversible process and no change for a reversible process.

- is equivalent to

This expression together with the associated reference state permits a design engineer working at the macroscopic scale (above the thermodynamic limit) to utilize the second law without directly measuring or considering entropy change in a total isolated system (see also Process engineer). Those changes have already been considered by the assumption that the system under consideration can reach equilibrium with the reference state without altering the reference state. An efficiency for a process or collection of processes that compares it to the reversible ideal may also be found (see Exergy efficiency).

This approach to the second law is widely utilized in engineering practice, environmental accounting, systems ecology, and other disciplines.

Direction of spontaneous processes

The second law determines whether a proposed physical or chemical process is forbidden or may occur spontaneously. For isolated systems, no energy is provided by the surroundings and the second law requires that the entropy of the system alone must increase: ΔS > 0. Examples of spontaneous physical processes in isolated systems include the following:

- 1) Heat can be transferred from a region of higher temperature to a lower temperature (but not the reverse).

- 2) Mechanical energy can be converted to thermal energy (but not the reverse).

- 3) A solute can move from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration (but not the reverse).

However, for some non-isolated systems which can exchange energy with their surroundings, the surroundings exchange enough heat with the system, or do sufficient work on the system, so that the processes occur in the opposite direction. This is possible provided the total entropy change of the system plus the surroundings is positive as required by the second law: ΔStot = ΔS + ΔSR > 0. For the three examples given above:

- 1) Heat can be transferred from a region of lower temperature to a higher temperature in a refrigerator or in a heat pump. These machines must provide sufficient work to the system.

- 2) Thermal energy can be converted to mechanical work in a heat engine, if sufficient heat is also expelled to the surroundings.

- 3) A solute can move from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration in the biochemical process of active transport, if sufficient work is provided by a concentration gradient of a chemical such as ATP or by an electrochemical gradient.

Second law in chemical thermodynamics

For a spontaneous chemical process in a closed system at constant temperature and pressure without non-PV work, the Clausius inequality ΔS > Q/Tsurr transforms into a condition for the change in Gibbs free energy

or dG < 0. For a similar process at constant temperature and volume, the change in Helmholtz free energy must be negative, . Thus, a negative value of the change in free energy (G or A) is a necessary condition for a process to be spontaneous. This is the most useful form of the second law of thermodynamics in chemistry, where free-energy changes can be calculated from tabulated enthalpies of formation and standard molar entropies of reactants and products. The chemical equilibrium condition at constant T and p without electrical work is dG = 0.

History

See also: History of entropy

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its surroundings.

Recognizing the significance of James Prescott Joule's work on the conservation of energy, Rudolf Clausius was the first to formulate the second law during 1850, in this form: heat does not flow spontaneously from cold to hot bodies. While common knowledge now, this was contrary to the caloric theory of heat popular at the time, which considered heat as a fluid. From there he was able to infer the principle of Sadi Carnot and the definition of entropy (1865).

Established during the 19th century, the Kelvin-Planck statement of the second law says, "It is impossible for any device that operates on a cycle to receive heat from a single reservoir and produce a net amount of work." This statement was shown to be equivalent to the statement of Clausius.

The ergodic hypothesis is also important for the Boltzmann approach. It says that, over long periods of time, the time spent in some region of the phase space of microstates with the same energy is proportional to the volume of this region, i.e. that all accessible microstates are equally probable over a long period of time. Equivalently, it says that time average and average over the statistical ensemble are the same.

There is a traditional doctrine, starting with Clausius, that entropy can be understood in terms of molecular 'disorder' within a macroscopic system. This doctrine is obsolescent.

Account given by Clausius

In 1865, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius stated what he called the "second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heat" in the following form:

where Q is heat, T is temperature and N is the "equivalence-value" of all uncompensated transformations involved in a cyclical process. Later, in 1865, Clausius would come to define "equivalence-value" as entropy. On the heels of this definition, that same year, the most famous version of the second law was read in a presentation at the Philosophical Society of Zurich on April 24, in which, in the end of his presentation, Clausius concludes:

The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.

This statement is the best-known phrasing of the second law. Because of the looseness of its language, e.g. universe, as well as lack of specific conditions, e.g. open, closed, or isolated, many people take this simple statement to mean that the second law of thermodynamics applies virtually to every subject imaginable. This is not true; this statement is only a simplified version of a more extended and precise description.

In terms of time variation, the mathematical statement of the second law for an isolated system undergoing an arbitrary transformation is:

where

- S is the entropy of the system and

- t is time.

The equality sign applies after equilibration. An alternative way of formulating of the second law for isolated systems is:

- with

with the sum of the rate of entropy production by all processes inside the system. The advantage of this formulation is that it shows the effect of the entropy production. The rate of entropy production is a very important concept since it determines (limits) the efficiency of thermal machines. Multiplied with ambient temperature it gives the so-called dissipated energy .

The expression of the second law for closed systems (so, allowing heat exchange and moving boundaries, but not exchange of matter) is:

- with

Here,

- is the heat flow into the system

- is the temperature at the point where the heat enters the system.

The equality sign holds in the case that only reversible processes take place inside the system. If irreversible processes take place (which is the case in real systems in operation) the >-sign holds. If heat is supplied to the system at several places we have to take the algebraic sum of the corresponding terms.

For open systems (also allowing exchange of matter):

- with

Here, is the flow of entropy into the system associated with the flow of matter entering the system. It should not be confused with the time derivative of the entropy. If matter is supplied at several places we have to take the algebraic sum of these contributions.

Statistical mechanics

Statistical mechanics gives an explanation for the second law by postulating that a material is composed of atoms and molecules which are in constant motion. A particular set of positions and velocities for each particle in the system is called a microstate of the system and because of the constant motion, the system is constantly changing its microstate. Statistical mechanics postulates that, in equilibrium, each microstate that the system might be in is equally likely to occur, and when this assumption is made, it leads directly to the conclusion that the second law must hold in a statistical sense. That is, the second law will hold on average, with a statistical variation on the order of 1/√N where N is the number of particles in the system. For everyday (macroscopic) situations, the probability that the second law will be violated is practically zero. However, for systems with a small number of particles, thermodynamic parameters, including the entropy, may show significant statistical deviations from that predicted by the second law. Classical thermodynamic theory does not deal with these statistical variations.

Derivation from statistical mechanics

Further information: H-theoremThe first mechanical argument of the Kinetic theory of gases that molecular collisions entail an equalization of temperatures and hence a tendency towards equilibrium was due to James Clerk Maxwell in 1860; Ludwig Boltzmann with his H-theorem of 1872 also argued that due to collisions gases should over time tend toward the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Due to Loschmidt's paradox, derivations of the second law have to make an assumption regarding the past, namely that the system is uncorrelated at some time in the past; this allows for simple probabilistic treatment. This assumption is usually thought as a boundary condition, and thus the second law is ultimately a consequence of the initial conditions somewhere in the past, probably at the beginning of the universe (the Big Bang), though other scenarios have also been suggested.

Given these assumptions, in statistical mechanics, the second law is not a postulate, rather it is a consequence of the fundamental postulate, also known as the equal prior probability postulate, so long as one is clear that simple probability arguments are applied only to the future, while for the past there are auxiliary sources of information which tell us that it was low entropy. The first part of the second law, which states that the entropy of a thermally isolated system can only increase, is a trivial consequence of the equal prior probability postulate, if we restrict the notion of the entropy to systems in thermal equilibrium. The entropy of an isolated system in thermal equilibrium containing an amount of energy of is:

where is the number of quantum states in a small interval between and . Here is a macroscopically small energy interval that is kept fixed. Strictly speaking this means that the entropy depends on the choice of . However, in the thermodynamic limit (i.e. in the limit of infinitely large system size), the specific entropy (entropy per unit volume or per unit mass) does not depend on .

Suppose we have an isolated system whose macroscopic state is specified by a number of variables. These macroscopic variables can, e.g., refer to the total volume, the positions of pistons in the system, etc. Then will depend on the values of these variables. If a variable is not fixed, (e.g. we do not clamp a piston in a certain position), then because all the accessible states are equally likely in equilibrium, the free variable in equilibrium will be such that is maximized at the given energy of the isolated system as that is the most probable situation in equilibrium.

If the variable was initially fixed to some value then upon release and when the new equilibrium has been reached, the fact the variable will adjust itself so that is maximized, implies that the entropy will have increased or it will have stayed the same (if the value at which the variable was fixed happened to be the equilibrium value). Suppose we start from an equilibrium situation and we suddenly remove a constraint on a variable. Then right after we do this, there are a number of accessible microstates, but equilibrium has not yet been reached, so the actual probabilities of the system being in some accessible state are not yet equal to the prior probability of . We have already seen that in the final equilibrium state, the entropy will have increased or have stayed the same relative to the previous equilibrium state. Boltzmann's H-theorem, however, proves that the quantity H increases monotonically as a function of time during the intermediate out of equilibrium state.

Derivation of the entropy change for reversible processes

The second part of the second law states that the entropy change of a system undergoing a reversible process is given by:

where the temperature is defined as:

See Microcanonical ensemble for the justification for this definition. Suppose that the system has some external parameter, x, that can be changed. In general, the energy eigenstates of the system will depend on x. According to the adiabatic theorem of quantum mechanics, in the limit of an infinitely slow change of the system's Hamiltonian, the system will stay in the same energy eigenstate and thus change its energy according to the change in energy of the energy eigenstate it is in.

The generalized force, X, corresponding to the external variable x is defined such that is the work performed by the system if x is increased by an amount dx. For example, if x is the volume, then X is the pressure. The generalized force for a system known to be in energy eigenstate is given by:

Since the system can be in any energy eigenstate within an interval of , we define the generalized force for the system as the expectation value of the above expression:

To evaluate the average, we partition the energy eigenstates by counting how many of them have a value for within a range between and . Calling this number , we have:

The average defining the generalized force can now be written:

We can relate this to the derivative of the entropy with respect to x at constant energy E as follows. Suppose we change x to x + dx. Then will change because the energy eigenstates depend on x, causing energy eigenstates to move into or out of the range between and . Let's focus again on the energy eigenstates for which lies within the range between and . Since these energy eigenstates increase in energy by Y dx, all such energy eigenstates that are in the interval ranging from E – Y dx to E move from below E to above E. There are

such energy eigenstates. If , all these energy eigenstates will move into the range between and and contribute to an increase in . The number of energy eigenstates that move from below to above is given by . The difference

is thus the net contribution to the increase in . If Y dx is larger than there will be the energy eigenstates that move from below E to above . They are counted in both and , therefore the above expression is also valid in that case.

Expressing the above expression as a derivative with respect to E and summing over Y yields the expression:

The logarithmic derivative of with respect to x is thus given by:

The first term is intensive, i.e. it does not scale with system size. In contrast, the last term scales as the inverse system size and will thus vanish in the thermodynamic limit. We have thus found that:

Combining this with

gives:

Derivation for systems described by the canonical ensemble

If a system is in thermal contact with a heat bath at some temperature T then, in equilibrium, the probability distribution over the energy eigenvalues are given by the canonical ensemble:

Here Z is a factor that normalizes the sum of all the probabilities to 1, this function is known as the partition function. We now consider an infinitesimal reversible change in the temperature and in the external parameters on which the energy levels depend. It follows from the general formula for the entropy:

that

Inserting the formula for for the canonical ensemble in here gives:

Initial conditions at the Big Bang

Further information: Past hypothesisAs elaborated above, it is thought that the second law of thermodynamics is a result of the very low-entropy initial conditions at the Big Bang. From a statistical point of view, these were very special conditions. On the other hand, they were quite simple, as the universe - or at least the part thereof from which the observable universe developed - seems to have been extremely uniform.

This may seem somewhat paradoxical, since in many physical systems uniform conditions (e.g. mixed rather than separated gases) have high entropy. The paradox is solved once realizing that gravitational systems have negative heat capacity, so that when gravity is important, uniform conditions (e.g. gas of uniform density) in fact have lower entropy compared to non-uniform ones (e.g. black holes in empty space). Yet another approach is that the universe had high (or even maximal) entropy given its size, but as the universe grew it rapidly came out of thermodynamic equilibrium, its entropy only slightly increased compared to the increase in maximal possible entropy, and thus it has arrived at a very low entropy when compared to the much larger possible maximum given its later size.

As for the reason why initial conditions were such, one suggestion is that cosmological inflation was enough to wipe off non-smoothness, while another is that the universe was created spontaneously where the mechanism of creation implies low-entropy initial conditions.

Living organisms

There are two principal ways of formulating thermodynamics, (a) through passages from one state of thermodynamic equilibrium to another, and (b) through cyclic processes, by which the system is left unchanged, while the total entropy of the surroundings is increased. These two ways help to understand the processes of life. The thermodynamics of living organisms has been considered by many authors, including Erwin Schrödinger (in his book What is Life?) and Léon Brillouin.

To a fair approximation, living organisms may be considered as examples of (b). Approximately, an animal's physical state cycles by the day, leaving the animal nearly unchanged. Animals take in food, water, and oxygen, and, as a result of metabolism, give out breakdown products and heat. Plants take in radiative energy from the sun, which may be regarded as heat, and carbon dioxide and water. They give out oxygen. In this way they grow. Eventually they die, and their remains rot away, turning mostly back into carbon dioxide and water. This can be regarded as a cyclic process. Overall, the sunlight is from a high temperature source, the sun, and its energy is passed to a lower temperature sink, i.e. radiated into space. This is an increase of entropy of the surroundings of the plant. Thus animals and plants obey the second law of thermodynamics, considered in terms of cyclic processes.

Furthermore, the ability of living organisms to grow and increase in complexity, as well as to form correlations with their environment in the form of adaption and memory, is not opposed to the second law – rather, it is akin to general results following from it: Under some definitions, an increase in entropy also results in an increase in complexity, and for a finite system interacting with finite reservoirs, an increase in entropy is equivalent to an increase in correlations between the system and the reservoirs.

Living organisms may be considered as open systems, because matter passes into and out from them. Thermodynamics of open systems is currently often considered in terms of passages from one state of thermodynamic equilibrium to another, or in terms of flows in the approximation of local thermodynamic equilibrium. The problem for living organisms may be further simplified by the approximation of assuming a steady state with unchanging flows. General principles of entropy production for such approximations are a subject of ongoing research.

Gravitational systems

Commonly, systems for which gravity is not important have a positive heat capacity, meaning that their temperature rises with their internal energy. Therefore, when energy flows from a high-temperature object to a low-temperature object, the source temperature decreases while the sink temperature is increased; hence temperature differences tend to diminish over time.

This is not always the case for systems in which the gravitational force is important: systems that are bound by their own gravity, such as stars, can have negative heat capacities. As they contract, both their total energy and their entropy decrease but their internal temperature may increase. This can be significant for protostars and even gas giant planets such as Jupiter. When the entropy of the black-body radiation emitted by the bodies is included, however, the total entropy of the system can be shown to increase even as the entropy of the planet or star decreases.

Non-equilibrium states

Main article: Non-equilibrium thermodynamicsThe theory of classical or equilibrium thermodynamics is idealized. A main postulate or assumption, often not even explicitly stated, is the existence of systems in their own internal states of thermodynamic equilibrium. In general, a region of space containing a physical system at a given time, that may be found in nature, is not in thermodynamic equilibrium, read in the most stringent terms. In looser terms, nothing in the entire universe is or has ever been truly in exact thermodynamic equilibrium.

For purposes of physical analysis, it is often enough convenient to make an assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium. Such an assumption may rely on trial and error for its justification. If the assumption is justified, it can often be very valuable and useful because it makes available the theory of thermodynamics. Elements of the equilibrium assumption are that a system is observed to be unchanging over an indefinitely long time, and that there are so many particles in a system, that its particulate nature can be entirely ignored. Under such an equilibrium assumption, in general, there are no macroscopically detectable fluctuations. There is an exception, the case of critical states, which exhibit to the naked eye the phenomenon of critical opalescence. For laboratory studies of critical states, exceptionally long observation times are needed.

In all cases, the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium, once made, implies as a consequence that no putative candidate "fluctuation" alters the entropy of the system.

It can easily happen that a physical system exhibits internal macroscopic changes that are fast enough to invalidate the assumption of the constancy of the entropy. Or that a physical system has so few particles that the particulate nature is manifest in observable fluctuations. Then the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium is to be abandoned. There is no unqualified general definition of entropy for non-equilibrium states.

There are intermediate cases, in which the assumption of local thermodynamic equilibrium is a very good approximation, but strictly speaking it is still an approximation, not theoretically ideal.

For non-equilibrium situations in general, it may be useful to consider statistical mechanical definitions of other quantities that may be conveniently called 'entropy', but they should not be confused or conflated with thermodynamic entropy properly defined for the second law. These other quantities indeed belong to statistical mechanics, not to thermodynamics, the primary realm of the second law.

The physics of macroscopically observable fluctuations is beyond the scope of this article.

Arrow of time

See also: Arrow of time and Entropy (arrow of time)The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law that is not symmetric to reversal of the time direction. This does not conflict with symmetries observed in the fundamental laws of physics (particularly CPT symmetry) since the second law applies statistically on time-asymmetric boundary conditions. The second law has been related to the difference between moving forwards and backwards in time, or to the principle that cause precedes effect (the causal arrow of time, or causality).

Irreversibility

Irreversibility in thermodynamic processes is a consequence of the asymmetric character of thermodynamic operations, and not of any internally irreversible microscopic properties of the bodies. Thermodynamic operations are macroscopic external interventions imposed on the participating bodies, not derived from their internal properties. There are reputed "paradoxes" that arise from failure to recognize this.

Loschmidt's paradox

Main article: Loschmidt's paradoxLoschmidt's paradox, also known as the reversibility paradox, is the objection that it should not be possible to deduce an irreversible process from the time-symmetric dynamics that describe the microscopic evolution of a macroscopic system.

In the opinion of Schrödinger, "It is now quite obvious in what manner you have to reformulate the law of entropy – or for that matter, all other irreversible statements – so that they be capable of being derived from reversible models. You must not speak of one isolated system but at least of two, which you may for the moment consider isolated from the rest of the world, but not always from each other." The two systems are isolated from each other by the wall, until it is removed by the thermodynamic operation, as envisaged by the law. The thermodynamic operation is externally imposed, not subject to the reversible microscopic dynamical laws that govern the constituents of the systems. It is the cause of the irreversibility. The statement of the law in this present article complies with Schrödinger's advice. The cause–effect relation is logically prior to the second law, not derived from it. This reaffirms Albert Einstein's postulates that cornerstone Special and General Relativity - that the flow of time is irreversible, however it is relative. Cause must precede effect, but only within the constraints as defined explicitly within General Relativity (or Special Relativity, depending on the local spacetime conditions). Good examples of this are the Ladder Paradox, time dilation and length contraction exhibited by objects approaching the velocity of light or within proximity of a super-dense region of mass/energy - e.g. black holes, neutron stars, magnetars and quasars.

Poincaré recurrence theorem

Main article: Poincaré recurrence theoremThe Poincaré recurrence theorem considers a theoretical microscopic description of an isolated physical system. This may be considered as a model of a thermodynamic system after a thermodynamic operation has removed an internal wall. The system will, after a sufficiently long time, return to a microscopically defined state very close to the initial one. The Poincaré recurrence time is the length of time elapsed until the return. It is exceedingly long, likely longer than the life of the universe, and depends sensitively on the geometry of the wall that was removed by the thermodynamic operation. The recurrence theorem may be perceived as apparently contradicting the second law of thermodynamics. More obviously, however, it is simply a microscopic model of thermodynamic equilibrium in an isolated system formed by removal of a wall between two systems. For a typical thermodynamical system, the recurrence time is so large (many many times longer than the lifetime of the universe) that, for all practical purposes, one cannot observe the recurrence. One might wish, nevertheless, to imagine that one could wait for the Poincaré recurrence, and then re-insert the wall that was removed by the thermodynamic operation. It is then evident that the appearance of irreversibility is due to the utter unpredictability of the Poincaré recurrence given only that the initial state was one of thermodynamic equilibrium, as is the case in macroscopic thermodynamics. Even if one could wait for it, one has no practical possibility of picking the right instant at which to re-insert the wall. The Poincaré recurrence theorem provides a solution to Loschmidt's paradox. If an isolated thermodynamic system could be monitored over increasingly many multiples of the average Poincaré recurrence time, the thermodynamic behavior of the system would become invariant under time reversal.

Maxwell's demon

Main article: Maxwell's demon

James Clerk Maxwell imagined one container divided into two parts, A and B. Both parts are filled with the same gas at equal temperatures and placed next to each other, separated by a wall. Observing the molecules on both sides, an imaginary demon guards a microscopic trapdoor in the wall. When a faster-than-average molecule from A flies towards the trapdoor, the demon opens it, and the molecule will fly from A to B. The average speed of the molecules in B will have increased while in A they will have slowed down on average. Since average molecular speed corresponds to temperature, the temperature decreases in A and increases in B, contrary to the second law of thermodynamics.

One response to this question was suggested in 1929 by Leó Szilárd and later by Léon Brillouin. Szilárd pointed out that a real-life Maxwell's demon would need to have some means of measuring molecular speed, and that the act of acquiring information would require an expenditure of energy. Likewise, Brillouin demonstrated that the decrease in entropy caused by the demon would be less than the entropy produced by choosing molecules based on their speed.

Maxwell's 'demon' repeatedly alters the permeability of the wall between A and B. It is therefore performing thermodynamic operations on a microscopic scale, not just observing ordinary spontaneous or natural macroscopic thermodynamic processes.

Quotations

The law that entropy always increases holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations – then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation – well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

— Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

There have been nearly as many formulations of the second law as there have been discussions of it.

— Philosopher / Physicist P.W. Bridgman, (1941)

Clausius is the author of the sibyllic utterance, "The energy of the universe is constant; the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum." The objectives of continuum thermomechanics stop far short of explaining the "universe", but within that theory we may easily derive an explicit statement in some ways reminiscent of Clausius, but referring only to a modest object: an isolated body of finite size.

— Truesdell, C., Muncaster, R. G. (1980). Fundamentals of Maxwell's Kinetic Theory of a Simple Monatomic Gas, Treated as a Branch of Rational Mechanics, Academic Press, New York, ISBN 0-12-701350-4, p. 17.

See also

- Zeroth law of thermodynamics

- First law of thermodynamics

- Third law of thermodynamics

- Clausius–Duhem inequality

- Fluctuation theorem

- Heat death of the universe

- History of thermodynamics

- Jarzynski equality

- Laws of thermodynamics

- Maximum entropy thermodynamics

- Quantum thermodynamics

- Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire

- Relativistic heat conduction

- Thermal diode

- Thermodynamic equilibrium

References

- Reichl, Linda (1980). A Modern Course in Statistical Physics. Edward Arnold. p. 9. ISBN 0-7131-2789-9.

- ^ Rao, Y. V. C. (1997). Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics. Universities Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-81-7371-048-3.

- Young, H. D; Freedman, R. A. (2004). University Physics, 11th edition. Pearson. p. 764.

- "5.2 Axiomatic Statements of the Laws of Thermodynamics". www.web.mit.edu. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- {David Sanborn Scott, The arrow of time, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 28, Issue 2, 2003, Pages 147-149, ISSN 0360-3199}

- Carroll, Sean (2010). From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-95133-9.

- Jaffe, R.L.; Taylor, W. (2018). The Physics of Energy. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 150, n259, 772, 743. ISBN 978-1-107-01665-1.

- David L. Chandler (2011-05-19). "Explained: The Carnot Limit".

- Planck, M. (1897/1903), pp. 40–41.

- Munster A. (1970), pp. 8–9, 50–51.

- Mandl 1988

- Planck, M. (1897/1903), pp. 79–107.

- Bailyn, M. (1994), Section 71, pp. 113–154.

- Bailyn, M. (1994), p. 120.

- ^ Mortimer, R.G. (2008). Physical Chemistry. Elsevier Science. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-12-370617-1.

- Fermi, E. (2012). Thermodynamics. Dover Books on Physics. Dover Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-486-13485-7.

- Adkins, C.J. (1968/1983), p. 75.

- ^ Münster, A. (1970), p. 45.

- ^ Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).Principles of Modern Chemistry, Brooks Cole. p. 617. ISBN 978-1305079113

- Pokrovskii V.N. (2005) Extended thermodynamics in a discrete-system approach, Eur. J. Phys. vol. 26, 769–781.

- Pokrovskii, Vladimir N. (2013). "A Derivation of the Main Relations of Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics". ISRN Thermodynamics. 2013: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2013/906136.

- J. S. Dugdale (1996). Entropy and its Physical Meaning. Taylor & Francis. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7484-0569-5.

This law is the basis of temperature.

- Zemansky, M.W. (1968), pp. 207–209.

- Quinn, T.J. (1983), p. 8.

- "Concept and Statements of the Second Law". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- Lieb & Yngvason (1999).

- Rao (2004), p. 213.

- Carnot, S. (1824/1986).

- Carnot, S. (1824/1986), p. 51.

- Carnot, S. (1824/1986), p. 46.

- Carnot, S. (1824/1986), p. 68.

- Truesdell, C. (1980), Chapter 5.

- Adkins, C.J. (1968/1983), pp. 56–58.

- Münster, A. (1970), p. 11.

- Kondepudi, D., Prigogine, I. (1998), pp.67–75.

- Lebon, G., Jou, D., Casas-Vázquez, J. (2008), p. 10.

- Eu, B.C. (2002), pp. 32–35.

- Clausius (1850).

- Clausius (1854), p. 86.

- Thomson (1851).

- Planck, M. (1897/1903), p. 86.

- Roberts, J.K., Miller, A.R. (1928/1960), p. 319.

- ter Haar, D., Wergeland, H. (1966), p. 17.

- Planck, M. (1897/1903), p. 100.

- Planck, M. (1926), p. 463, translation by Uffink, J. (2003), p. 131.

- Roberts, J.K., Miller, A.R. (1928/1960), p. 382. This source is partly verbatim from Planck's statement, but does not cite Planck. This source calls the statement the principle of the increase of entropy.

- Uhlenbeck, G.E., Ford, G.W. (1963), p. 16.

- Carathéodory, C. (1909).

- Buchdahl, H.A. (1966), p. 68.

- Sychev, V. V. (1991). The Differential Equations of Thermodynamics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-56032-121-7.

- ^ Lieb & Yngvason (1999), p. 49.

- ^ Planck, M. (1926).

- Buchdahl, H.A. (1966), p. 69.

- Uffink, J. (2003), pp. 129–132.

- Truesdell, C., Muncaster, R.G. (1980). Fundamentals of Maxwell's Kinetic Theory of a Simple Monatomic Gas, Treated as a Branch of Rational Mechanics, Academic Press, New York, ISBN 0-12-701350-4, p. 15.

- Planck, M. (1897/1903), p. 81.

- Planck, M. (1926), p. 457, Misplaced Pages editor's translation.

- Lieb, E.H., Yngvason, J. (2003), p. 149.

- Borgnakke, C., Sonntag., R.E. (2009), p. 304.

- Grubbström, Robert W. (1985). "Towards a Generalized Exergy Concept". In Van Gool, W.; Bruggink, J.J.C. (eds.). Energy and time in the economic and physical sciences. North-Holland. pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-0-444-87748-2.

- Callen, H.B. (1960/1985), Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, (first edition 1960), second edition 1985, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN 0-471-86256-8, pp. 146–148.

- Wright, S.E. (December 2007). "The Clausius inequality corrected for heat transfer involving radiation". International Journal of Engineering Science. 45 (12): 1007–1016. doi:10.1016/j.ijengsci.2007.08.005. ISSN 0020-7225.

- Planck, Max (1914). "Translation by Morton Mausius, The Theory of Heat Radiation". Dover Publications, NY.

- Landsberg, P T; Tonge, G (April 1979). "Thermodynamics of the conversion of diluted radiation". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 12 (4): 551–562. Bibcode:1979JPhA...12..551L. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/12/4/015. ISSN 0305-4470.

- Wright (2001). "On the entropy of radiative heat transfer in engineering thermodynamics". Int. J. Eng. Sci. 39 (15): 1691–1706. doi:10.1016/S0020-7225(01)00024-6.

- Wright, S.E.; Rosen, M.A.; Scott, D.S.; Haddow, J.B. (January 2002). "The exergy flux of radiative heat transfer for the special case of blackbody radiation". Exergy. 2 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1016/s1164-0235(01)00040-1. ISSN 1164-0235.

- Wright, S.E.; Rosen, M.A.; Scott, D.S.; Haddow, J.B. (January 2002). "The exergy flux of radiative heat transfer with an arbitrary spectrum". Exergy. 2 (2): 69–77. doi:10.1016/s1164-0235(01)00041-3. ISSN 1164-0235.

- Wright, Sean E.; Rosen, Marc A. (2004-02-01). "Exergetic Efficiencies and the Exergy Content of Terrestrial Solar Radiation". Journal of Solar Energy Engineering. 126 (1): 673–676. doi:10.1115/1.1636796. ISSN 0199-6231.

- ^ Wright, S.E. (February 2017). "A generalized and explicit conceptual statement of the principle of the second law of thermodynamics". International Journal of Engineering Science. 111: 12–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijengsci.2016.11.002. ISSN 0020-7225.

- Clausius theorem at Wolfram Research

- Planck, M. (1945). Treatise on Thermodynamics. Dover Publications. p. §90.

eq.(39) & (40)

. - Denbigh, K.G., Denbigh, J.S. (1985). Entropy in Relation to Incomplete Knowledge, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 0-521-25677-1, pp. 43–44.

- Grandy, W.T., Jr (2008). Entropy and the Time Evolution of Macroscopic Systems, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-954617-6, pp. 55–58.

- Entropy Sites — A Guide Content selected by Frank L. Lambert

- Clausius (1867).

- Gyenis, Balazs (2017). "Maxwell and the normal distribution: A colored story of probability, independence, and tendency towards equilibrium". Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 57: 53–65. arXiv:1702.01411. Bibcode:2017SHPMP..57...53G. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2017.01.001. S2CID 38272381.

- Hawking, SW (1985). "Arrow of time in cosmology". Phys. Rev. D. 32 (10): 2489–2495. Bibcode:1985PhRvD..32.2489H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.32.2489. PMID 9956019.

- Greene, Brian (2004). The Fabric of the Cosmos. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-375-41288-2.

- Lebowitz, Joel L. (September 1993). "Boltzmann's Entropy and Time's Arrow" (PDF). Physics Today. 46 (9): 32–38. Bibcode:1993PhT....46i..32L. doi:10.1063/1.881363. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- Young, H. D; Freedman, R. A. (2004). University Physics, 11th edition. Pearson. p. 731.

- Carroll, S. (2017). The big picture: on the origins of life, meaning, and the universe itself. Penguin.

- Greene, B. (2004). The fabric of the cosmos: Space, time, and the texture of reality. Knopf.

- Davies, P. C. (1983). Inflation and time asymmetry in the universe. Nature, 301(5899), 398–400.

- Physicists Debate Hawking's Idea That the Universe Had No Beginning. Wolchover, N. Quantmagazine, June 6, 2019. Retrieved 2020-11-28

- Brillouin, L. (2013). Science and Information Theory. Dover Books on Physics. Dover Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-486-49755-6. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Ladyman, James; Lambert, James; Wiesner, Karoline (19 June 2012). "What is a complex system?". European Journal for Philosophy of Science. 3 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 33–67. doi:10.1007/s13194-012-0056-8. ISSN 1879-4912. S2CID 18787276.

- Esposito, Massimiliano; Lindenberg, Katja; Van den Broeck, Christian (15 January 2010). "Entropy production as correlation between system and reservoir". New Journal of Physics. 12 (1): 013013. arXiv:0908.1125. Bibcode:2010NJPh...12a3013E. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/12/1/013013. ISSN 1367-2630.

- Baez, John (7 August 2000). "Can Gravity Decrease Entropy?". UC Riverside Department of Mathematics. University of California Riverside. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

... gravitationally bound ball of gas has a negative specific heat!

- Baez, John (7 August 2000). "Can Gravity Decrease Entropy?". UC Riverside Department of Mathematics. University of California Riverside. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Grandy, W.T. (Jr) (2008), p. 151.

- Callen, H.B. (1960/1985), p. 15.

- Lieb, E.H., Yngvason, J. (2003), p. 190.

- Gyarmati, I. (1967/1970), pp. 4-14.

- Glansdorff, P., Prigogine, I. (1971).

- Müller, I. (1985).

- Müller, I. (2003).

- Callender, Craig (29 July 2011). "Thermodynamic Asymmetry in Time". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Halliwell, J.J.; et al. (1994). "6". Physical Origins of Time Asymmetry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56837-1.

- Schrödinger, E. (1950), p. 192.

- ^ "Maxwell's demon | physics | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Norton, John (3 July 2013). "All Shook Up: Fluctuations, Maxwell's Demon and the Thermodynamics of Computation". Entropy. 15 (12): 4432–4483. Bibcode:2013Entrp..15.4432N. doi:10.3390/e15104432.

Sources

- Adkins, C. J. (1983). Equilibrium thermodynamics (1st ed. 1968, 3rd ed.). Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25445-0. OCLC 9132054.

- Atkins, P.W., de Paula, J. (2006). Atkins' Physical Chemistry, eighth edition, W.H. Freeman, New York, ISBN 978-0-7167-8759-4.

- Attard, P. (2012). Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics: Foundations and Applications, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, ISBN 978-0-19-966276-0.

- Baierlein, R. (1999). Thermal Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 0-521-59082-5.

- Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3.

- Blundell, Stephen J.; Blundell, Katherine M. (2010). Concepts in thermal physics (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562091.001.0001. ISBN 9780199562107. OCLC 607907330.

- Boltzmann, L. (1896/1964). Lectures on Gas Theory, translated by S.G. Brush, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Borgnakke, C., Sonntag., R.E. (2009). Fundamentals of Thermodynamics, seventh edition, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-04192-5.

- Buchdahl, H.A. (1966). The Concepts of Classical Thermodynamics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

- Bridgman, P.W. (1943). The Nature of Thermodynamics, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- Callen, H.B. (1960/1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, (1st edition 1960) 2nd edition 1985, Wiley, New York, ISBN 0-471-86256-8.

- C. Carathéodory (1909). "Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Thermodynamik". Mathematische Annalen. 67 (3): 355–386. doi:10.1007/bf01450409. S2CID 118230148. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

Axiom II: In jeder beliebigen Umgebung eines willkürlich vorgeschriebenen Anfangszustandes gibt es Zustände, die durch adiabatische Zustandsänderungen nicht beliebig approximiert werden können. (p.363)

. A translation may be found here. Also a mostly reliable translation is to be found at Kestin, J. (1976). The Second Law of Thermodynamics, Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, Stroudsburg PA. - Carnot, S. (1824/1986). Reflections on the motive power of fire, Manchester University Press, Manchester UK, ISBN 0-7190-1741-6. Also here.

- Chapman, S., Cowling, T.G. (1939/1970). The Mathematical Theory of Non-uniform gases. An Account of the Kinetic Theory of Viscosity, Thermal Conduction and Diffusion in Gases, third edition 1970, Cambridge University Press, London.