(Redirected from Kirchhoff stress tensor )

In continuum mechanics , the most commonly used measure of stress is the Cauchy stress tensor , often called simply the stress tensor or "true stress". However, several alternative measures of stress can be defined:

The Kirchhoff stress (

τ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

The nominal stress (

N

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}}

The Piola–Kirchhoff stress tensors

The first Piola–Kirchhoff stress (

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}}

P

=

N

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}={\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}}

The second Piola–Kirchhoff stress or PK2 stress (

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

The Biot stress (

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

Definitions

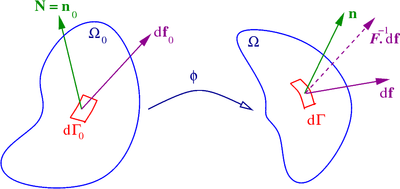

Consider the situation shown in the following figure. The following definitions use the notations shown in the figure.

Quantities used in the definition of stress measures

In the reference configuration

Ω

0

{\displaystyle \Omega _{0}}

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle d\Gamma _{0}}

N

≡

n

0

{\displaystyle \mathbf {N} \equiv \mathbf {n} _{0}}

t

0

{\displaystyle \mathbf {t} _{0}}

d

f

0

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} _{0}}

Ω

{\displaystyle \Omega }

d

Γ

{\displaystyle d\Gamma }

n

{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} }

t

{\displaystyle \mathbf {t} }

d

f

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} }

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

deformation gradient tensor ,

J

{\displaystyle J}

Cauchy stress

The Cauchy stress (or true stress) is a measure of the force acting on an element of area in the deformed configuration. This tensor is symmetric and is defined via

d

f

=

t

d

Γ

=

σ

T

⋅

n

d

Γ

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} =\mathbf {t} ~d\Gamma ={\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} ~d\Gamma }

or

t

=

σ

T

⋅

n

{\displaystyle \mathbf {t} ={\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} }

where

t

{\displaystyle \mathbf {t} }

n

{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} }

Kirchhoff stress

The quantity,

τ

=

J

σ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}=J~{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

is called the Kirchhoff stress tensor , with

J

{\displaystyle J}

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

weighted Cauchy stress tensor as well.

Piola–Kirchhoff stress

Main article: Piola–Kirchhoff stress tensor

Nominal stress/First Piola–Kirchhoff stress

The nominal stress

N

=

P

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}={\boldsymbol {P}}^{T}}

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}}

d

f

=

t

d

Γ

=

N

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

=

P

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} =\mathbf {t} ~d\Gamma ={\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}={\boldsymbol {P}}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

or

t

0

=

t

d

Γ

d

Γ

0

=

N

T

⋅

n

0

=

P

⋅

n

0

{\displaystyle \mathbf {t} _{0}=\mathbf {t} {\dfrac {d{\Gamma }}{d\Gamma _{0}}}={\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}={\boldsymbol {P}}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}}

This stress is unsymmetric and is a two-point tensor like the deformation gradient.

Second Piola–Kirchhoff stress

If we pull back

d

f

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} }

d

f

0

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} _{0}}

d

f

0

=

F

−

1

⋅

d

f

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot d\mathbf {f} }

or,

d

f

0

=

F

−

1

⋅

N

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

=

F

−

1

⋅

t

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot \mathbf {t} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

The PK2 stress (

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

d

f

0

=

S

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

=

F

−

1

⋅

t

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} _{0}={\boldsymbol {S}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot \mathbf {t} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

Therefore,

S

T

⋅

n

0

=

F

−

1

⋅

t

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot \mathbf {t} _{0}}

Biot stress

The Biot stress is useful because it is energy conjugate to the right stretch tensor

U

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {U}}}

P

T

⋅

R

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {R}}}

R

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}}

polar decomposition of the deformation gradient. Therefore, the Biot stress tensor is defined as

T

=

1

2

(

R

T

⋅

P

+

P

T

⋅

R

)

.

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}={\tfrac {1}{2}}({\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {P}}+{\boldsymbol {P}}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {R}})~.}

The Biot stress is also called the Jaumann stress.

The quantity

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

R

T

d

f

=

(

P

T

⋅

R

)

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}~d\mathbf {f} =({\boldsymbol {P}}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {R}})^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

Relations

Relations between Cauchy stress and nominal stress

From Nanson's formula relating areas in the reference and deformed configurations:

n

d

Γ

=

J

F

−

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} ~d\Gamma =J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

Now,

σ

T

⋅

n

d

Γ

=

d

f

=

N

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} ~d\Gamma =d\mathbf {f} ={\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

Hence,

σ

T

⋅

(

J

F

−

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

)

=

N

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot (J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0})={\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}}

or,

N

T

=

J

(

F

−

1

⋅

σ

)

T

=

J

σ

T

⋅

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}=J~({\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\sigma }})^{T}=J~{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

or,

N

=

J

F

−

1

⋅

σ

and

N

T

=

P

=

J

σ

T

⋅

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}=J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}\qquad {\text{and}}\qquad {\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}={\boldsymbol {P}}=J~{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}^{T}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

In index notation,

N

I

j

=

J

F

I

k

−

1

σ

k

j

and

P

i

J

=

J

σ

k

i

F

J

k

−

1

{\displaystyle N_{Ij}=J~F_{Ik}^{-1}~\sigma _{kj}\qquad {\text{and}}\qquad P_{iJ}=J~\sigma _{ki}~F_{Jk}^{-1}}

Therefore,

J

σ

=

F

⋅

N

=

F

⋅

P

T

.

{\displaystyle J~{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {N}}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {P}}^{T}~.}

Note that

N

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}}

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}}

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

Relations between nominal stress and second P–K stress

Recall that

N

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

=

d

f

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0}=d\mathbf {f} }

and

d

f

=

F

⋅

d

f

0

=

F

⋅

(

S

T

⋅

n

0

d

Γ

0

)

{\displaystyle d\mathbf {f} ={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot d\mathbf {f} _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot ({\boldsymbol {S}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}~d\Gamma _{0})}

Therefore,

N

T

⋅

n

0

=

F

⋅

S

T

⋅

n

0

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}^{T}\cdot \mathbf {n} _{0}}

or (using the symmetry of

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

N

=

S

⋅

F

T

and

P

=

F

⋅

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}={\boldsymbol {S}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}\qquad {\text{and}}\qquad {\boldsymbol {P}}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}}

In index notation,

N

I

j

=

S

I

K

F

j

K

T

and

P

i

J

=

F

i

K

S

K

J

{\displaystyle N_{Ij}=S_{IK}~F_{jK}^{T}\qquad {\text{and}}\qquad P_{iJ}=F_{iK}~S_{KJ}}

Alternatively, we can write

S

=

N

⋅

F

−

T

and

S

=

F

−

1

⋅

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}={\boldsymbol {N}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}\qquad {\text{and}}\qquad {\boldsymbol {S}}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {P}}}

Relations between Cauchy stress and second P–K stress

Recall that

N

=

J

F

−

1

⋅

σ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {N}}=J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

In terms of the 2nd PK stress, we have

S

⋅

F

T

=

J

F

−

1

⋅

σ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}=J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

Therefore,

S

=

J

F

−

1

⋅

σ

⋅

F

−

T

=

F

−

1

⋅

τ

⋅

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}=J~{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\tau }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

In index notation,

S

I

J

=

F

I

k

−

1

τ

k

l

F

J

l

−

1

{\displaystyle S_{IJ}=F_{Ik}^{-1}~\tau _{kl}~F_{Jl}^{-1}}

Since the Cauchy stress (and hence the Kirchhoff stress) is symmetric, the 2nd PK stress is also symmetric.

Alternatively, we can write

σ

=

J

−

1

F

⋅

S

⋅

F

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}=J^{-1}~{\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

or,

τ

=

F

⋅

S

⋅

F

T

.

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}~.}

Clearly, from definition of the push-forward and pull-back operations, we have

S

=

φ

∗

[

τ

]

=

F

−

1

⋅

τ

⋅

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}=\varphi ^{*}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}\cdot {\boldsymbol {\tau }}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

and

τ

=

φ

∗

[

S

]

=

F

⋅

S

⋅

F

T

.

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}=\varphi _{*}={\boldsymbol {F}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {S}}\cdot {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}~.}

Therefore,

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

τ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

F

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}}

τ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

Summary of conversion formula

Key:

J

=

det

(

F

)

,

C

=

F

T

F

=

U

2

,

F

=

R

U

,

R

T

=

R

−

1

,

{\displaystyle J=\det \left({\boldsymbol {F}}\right),\quad {\boldsymbol {C}}={\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {F}}={\boldsymbol {U}}^{2},\quad {\boldsymbol {F}}={\boldsymbol {R}}{\boldsymbol {U}},\quad {\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}={\boldsymbol {R}}^{-1},}

P

=

J

σ

F

−

T

,

τ

=

J

σ

,

S

=

J

F

−

1

σ

F

−

T

,

T

=

R

T

P

,

M

=

C

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}=J{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T},\quad {\boldsymbol {\tau }}=J{\boldsymbol {\sigma }},\quad {\boldsymbol {S}}=J{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T},\quad {\boldsymbol {T}}={\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {P}},\quad {\boldsymbol {M}}={\boldsymbol {C}}{\boldsymbol {S}}}

Conversion formulae

Equation for

σ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

τ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

M

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {M}}}

σ

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}=\,}

σ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

J

−

1

τ

{\displaystyle J^{-1}{\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

J

−

1

P

F

T

{\displaystyle J^{-1}{\boldsymbol {P}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

J

−

1

F

S

F

T

{\displaystyle J^{-1}{\boldsymbol {F}}{\boldsymbol {S}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

J

−

1

R

T

F

T

{\displaystyle J^{-1}{\boldsymbol {R}}{\boldsymbol {T}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

J

−

1

F

−

T

M

F

T

{\displaystyle J^{-1}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}{\boldsymbol {M}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

τ

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}=\,}

J

σ

{\displaystyle J{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}}

τ

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}}

P

F

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

F

S

F

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}{\boldsymbol {S}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

R

T

F

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}{\boldsymbol {T}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

F

−

T

M

F

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}{\boldsymbol {M}}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}}

P

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}=\,}

J

σ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle J{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

τ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {\tau }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {P}}}

F

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}{\boldsymbol {S}}}

R

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}{\boldsymbol {T}}}

F

−

T

M

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}{\boldsymbol {M}}}

S

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}=\,}

J

F

−

1

σ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle J{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

F

−

1

τ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {\tau }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

F

−

1

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {P}}}

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {S}}}

U

−

1

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {U}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {T}}}

C

−

1

M

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {C}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {M}}}

T

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}=\,}

J

R

T

σ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle J{\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

R

T

τ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {\tau }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

R

T

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {R}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {P}}}

U

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {U}}{\boldsymbol {S}}}

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {T}}}

U

−

1

M

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {U}}^{-1}{\boldsymbol {M}}}

M

=

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {M}}=\,}

J

F

T

σ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle J{\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {\sigma }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

F

T

τ

F

−

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {\tau }}{\boldsymbol {F}}^{-T}}

F

T

P

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {F}}^{T}{\boldsymbol {P}}}

C

S

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {C}}{\boldsymbol {S}}}

U

T

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {U}}{\boldsymbol {T}}}

M

{\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {M}}}

See also

References

Nonlinear Continuum Mechanics for Finite Element Analysis , Cambridge University Press.

Non-linear Elastic Deformations , Dover.

Theory of Elasticity , third edition

Three-Dimensional Elasticity ISBN 978-0-08-087541-5

Categories :

).

). ).

). ). This stress tensor is the transpose of the nominal stress (

). This stress tensor is the transpose of the nominal stress ( ).

). ).

). )

) , the outward normal to a surface element

, the outward normal to a surface element  is

is  and the traction acting on that surface (assuming it deforms like a generic vector belonging to the deformation) is

and the traction acting on that surface (assuming it deforms like a generic vector belonging to the deformation) is  leading to a force vector

leading to a force vector  . In the deformed configuration

. In the deformed configuration  , the surface element changes to

, the surface element changes to  with outward normal

with outward normal  and traction vector

and traction vector  leading to a force

leading to a force  . Note that this surface can either be a hypothetical cut inside the body or an actual surface. The quantity

. Note that this surface can either be a hypothetical cut inside the body or an actual surface. The quantity  is the

is the  is its determinant.

is its determinant.

is the transpose of the first Piola–Kirchhoff stress (PK1 stress, also called engineering stress)

is the transpose of the first Piola–Kirchhoff stress (PK1 stress, also called engineering stress)

. The Biot stress is defined as the symmetric part of the tensor

. The Biot stress is defined as the symmetric part of the tensor  where

where  is the rotation tensor obtained from a

is the rotation tensor obtained from a

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)

(non isotropy)