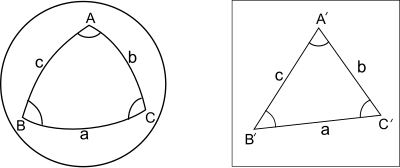

In geometry, Legendre's theorem on spherical triangles, named after Adrien-Marie Legendre, is stated as follows:

- Let ABC be a spherical triangle on the unit sphere with small sides a, b, c. Let A'B'C' be the planar triangle with the same sides. Then the angles of the spherical triangle exceed the corresponding angles of the planar triangle by approximately one third of the spherical excess (the spherical excess is the amount by which the sum of the three angles exceeds π).

The theorem was very important in simplifying the heavy numerical work in calculating the results of traditional (pre-GPS and pre-computer) geodetic surveys from about 1800 until the middle of the twentieth century.

The theorem was stated by Legendre (1787) who provided a proof in a supplement to the report of the measurement of the French meridional arc used in the definition of the metre. Legendre does not claim that he was the originator of the theorem despite the attribution to him. Tropfke (1903) maintains that the method was in common use by surveyors at the time and may have been used as early as 1740 by La Condamine for the calculation of the Peruvian meridional arc.

Girard's theorem states that the spherical excess of a triangle, E, is equal to its area, Δ, and therefore Legendre's theorem may be written as

The excess, or area, of small triangles is very small. For example, consider an equilateral spherical triangle with sides of 60 km on a spherical Earth of radius 6371 km; the side corresponds to an angular distance of 60/6371=.0094, or approximately 10 radians (subtending an angle of 0.57° at the centre). The area of such a small triangle is well approximated by that of a planar equilateral triangle with the same sides: = 0.0000433 radians corresponding to 8.9″.

When the sides of the triangles exceed 180 km, for which the excess is about 80″, the relations between the areas and the differences of the angles must be corrected by terms of fourth order in the sides, amounting to no more than 0.01″:

( is the area of the planar triangle.) This result was proved by Buzengeiger (1818).

The theorem may be extended to the ellipsoid if , , are calculated by dividing the true lengths by the square root of the product of the principal radii of curvature at the median latitude of the vertices (in place of a spherical radius). Gauss provided more exact formulae.

References

- Legendre (1798).

- Delambre (1798).

- Tropfke (1903).

- Buzengeiger (1818). An extended proof may be found in Osborne (2013) (Appendix D13). Other results are surveyed by Nádeník (2004).

- See Osborne (2013), Chapter 5.

- Gauss (1828), Art. 26–28.

Bibliography

- Buzengeiger, Karl Heribert Ignatz (1818), "Vergleichung zweier kleiner Dreiecke von gleichen Seiten, wovon das eine sphärisch, das andere eben ist", Zeitschrift für Astronomie und verwandte Wissenschaften, 6: 264–270

- Clarke, Alexander Ross (1880), Geodesy, Clarendon Press

- Delambre, Jean-Baptiste (1798), Méthodes analytiques pour la détermination d'un arc du méridien, Duprat, doi:10.3931/E-RARA-1836 – via ETH Zürich library

- Gauss, C. F. (1902) , General Investigations of Curved Surfaces of 1827 and 1825, Princeton Univ. Lib; English translation of Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas (Dieterich, Göttingen, 1828).

- Legendre, Adrien-Marie (1787), Mémoire sur les opérations trigonométriques, dont les résultats dépendant de la figure de la Terre, p. 7 (Article VI )

- Legendre, Adrien-Marie (1798), Méthode pour déterminer la longueur exacte du quart du méridien d'après les observations faites pour la mesure de l'arc compris entre Dunkerque et Barcelone, pp. 12–14 (Note III )

- Nádeník, Zbynek (2004), Legendre theorem on spherical triangles (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-16

- Osborne, Peter (2013), The Mercator Projections, archived from the original on 2013-09-24

- Tropfke, Johannes (1903), Geschichte der Elementar-Mathematik (Volume 2)., Verlag von Veit, p. 295

= 0.0000433 radians corresponding to 8.9″.

= 0.0000433 radians corresponding to 8.9″.

is the area of the planar triangle.) This result was proved by

is the area of the planar triangle.) This result was proved by  ,

,  ,

,  are calculated by dividing the true lengths by the square root of the product of the principal radii of curvature at the median latitude of the vertices (in place of a spherical radius). Gauss provided more exact formulae.

are calculated by dividing the true lengths by the square root of the product of the principal radii of curvature at the median latitude of the vertices (in place of a spherical radius). Gauss provided more exact formulae.