This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

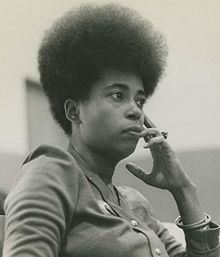

| Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce | |

|---|---|

Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce in class Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce in class | |

| Born | (1934-09-02)September 2, 1934 |

| Died | October 5, 2015(2015-10-05) (aged 81) |

| Occupation(s) | Educator, Mediator |

Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce (September 2, 1934 – October 5, 2015) was an American educator and international and domestic relations mediator.

Biography

Early life

Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce was born on September 2, 1934, at Harlem Hospital in New York, New York. She is the eldest of three children of John Abner DeLeaver of White Stone, Virginia and Flossie Alice White of Kilmarnock, Virginia.

In her youth, Pierce spent a lot of time with her maternal grandparents, Alice Roberta and Luther Doggett White on their 48-acre Kilmarnock farm in Lancaster County, Virginia. Her grandparents, denied a formal education, were dedicated to their children having the opportunity. At a time when the Virginia public school system limited African-American children to a sixth grade education, the White's sent their 6 children out of state to attend Dunbar High School (also known as the M Street School) in Washington, D.C., one of the few black high schools in the country.

Pierce, primarily, grew up in Harlem. The DeLeaver family was among the first to live in the Harlem River Houses in upper Manhattan, one of the first public housing projects in the nation. They attended Abyssinian Baptist Church, where Pierce sang in the choir. At age 9, she was baptized at the church.

Education

Pierce attended P.S. 46 in Manhattan, Edward W. Stitt Junior High School 164, and the Lincoln Park Honor School of the High School of Commerce in New York. She graduated from Brooklyn College and Hunter College in New York with a B.A. and M.S. degrees in education in 1955 and 1963, respectively.

She went on to earn a Juris Doctor degree from Rutgers University School of Law in Newark in 1980. While attending, she became a member of The Association of Black Law Students.

In addition, she received a post graduate certificate in management and administration from Harvard University in 1988. A lifelong learner, Pierce studied Asian and Hispanic art history at the graduate school of Georgia State University, and African art at Emory University and the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies.

Pierce's educational pursuits extend beyond the formal classroom, particularly her studies in the African Diaspora history. Early exposure to Africa was provided when as a child her paternal aunt, Dorothy DeLeaver Gibrilla, who was from the small town of White Stone, Virginia, married Claudius Adelejou Gibrilla of Sierra Leone, West Africa in 1937. When his country declared independence from Britain, Claude Gibrilla was named Consul General for New York. Pierce developed an appreciation of African-Americans' relationship to Africa through her frequent interactions with the Gibrillas. Mrs. Gibrilla gave Pierce the Yoruba name Modupe, meaning “I give thanks to God for watching over me.” Pierce's interest in the condition of black lives throughout the African Diaspora and the effects of African culture on the world later influenced her research projects and lectures.

Early career

Pierce began her professional career in 1955 as an elementary school teacher and guidance counselor in Harlem public schools. In 1965, upon completing her master's degree in educational counseling, she was recruited by Hunter College High School for the Gifted to assist them in the integration of larger numbers of black students into that exclusive institution.

In 1968, she resigned her position at Hunter to accept a position of Assistant to the Dean of the Faculty and Director of Human Resources at Barnard College, the elite women's college at Columbia University in New York. Pressured by the civil rights movement, and student sit-ins at Hamilton Hall, Barnard was faced with the need to enroll a more diverse student body at its Ivy League institution. To assist them with this campus-wide transition, Pierce became the first black administrator at the college. During her 3-year tenure, she negotiated a landmark, peer enforced drug-free policy for black students at this institution. Black women enrolled at Barnard organized under the name of Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters (B.O.S.S.) and became the first organized group of black students at the college. B.O.S.S. urged the college to develop a more culturally inclusive curriculum. As a result, the college newspaper, Columbia Spectator reported that Barnard College would establish an Afro-American major. While there, Pierce coordinated supportive services for these women, and for faculty, and carefully documented the evolution of B.O.S.S, which developed lasting friendships with many of the students. Among the many talented women attending Barnard at the time were author Thulani Davis and acclaimed playwright Ntozake Shange (Paulette Williams).

1970–1990

After her resignation from Barnard College in 1971, Pierce renewed her guidance counselor license and returned briefly to the Harlem public schools. In 1976, she began what would become a long-term association with the Berlitz School of Languages, the world's premier provider of foreign language services. Pierce began as an instructor at the Berlitz Center in New York teaching English.

In 1981, she was recruited as a Berlitz management trainee and was assigned to manage Berlitz operations in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1984, she was promoted to district director of the New England Region (based in Boston) where she was responsible for sales, operations, human resources and the management of a Fortune 500 corporate client portfolio for Berlitz in four states.

In 1990, Lemoine Pierce was recruited as a Senior Associate by D.J. Miller & Associates (DJMA) a management consulting firm, when she relocated to Atlanta. There she researched government procurement policies and programs as a result of a landmark Supreme Court decision in Crosen v. City of Richmond. The case was a result of Mayor Maynard Jackson and his staff launching his Minority Business Enterprise (MBWE) program in 1973. MBWE required that all contractors doing business with the City of Atlanta in the future would have to demonstrate that a percentage of the work would be done by teams that included women and minority contractors. This affirmative action municipal government contracting program (the first in United States history) became the model throughout the country. However, in 1989, the program was successfully challenged and deemed unconstitutional.

Subsequently, cities throughout the nation were required to conduct disparity studies to provide proof of past societal discrimination in the construction industry that would justify the need for MBWE programs. Because of this experience with Maynard Jackson, DJMA was the national expert on the design and implementation of disparity studies. Pierce was assigned to research and write portions of several of the firm's disparity studies.

Following upon her work at DJMA, and her involvement with the development of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) programs in Georgia and throughout the United States, Pierce was recruited as an instructor by Morris Brown College. In 1996, she became a full-time professor in their newly formed Legal Studies program, the first such degree-granting program for undergraduates at an historically black college. She was tenured as an associate professor of Legal Studies.

1991–2004

In the continuation of DeLeaver's career, she had experience in divorce and child custody counseling. She was a consultant at the National Association of Black Social Workers. DeLeaver went on to be a consultant on the International Conflict Resolution Georgia Council for International Visitor, conducting dispute resolution seminars for visiting delegations across the world.

Pierce presented at the 1995 African American Women on Tour (AAWOT) Conference on conflict management.

She became a domestic violence consultant for the U.S. Naval Air Station, and also went back to teaching as a professor in several Georgia colleges and universities. She was an adjunct professor in the Department of Political Science and International Affairs at Kennasaw State University (KSU). She taught business law at the Mack J Robinson College of Business at Georgia State University (GSU) in 2004.

Research and published works

From the mid-1990s to early 2000s, DeLeaver was working on a research project involving the Georgia Department of Corrections. She was examining and researching the Bureau of Justice's special reports involving women and the impact of incarcerated parents on their children.

Much of DeLeaver's research and lectures were connected to her interests in the African Diaspora. In 1989, she was very curious about a thesis published in Zurich, Switzerland in 1975 by Fredrick R. Gutafuson called, "The Black Madonna of Einstedein: A Psychology Perspective." She wrote to the author requesting a copy of the original manuscript and he responded with a hand written note. He also included suggestions about other books to further her study: Zimmer's "Myths & Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization" and Woodman's "The Pregnant Virgin."

DeLeaver was once the editor of the monthly publication Cues & Views. She has published manuscripts including:

- "Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators" (American Arbitration Association/ American Bar Association/ Society of Professionals in Dispute Resolution. 1994.)

- "The Significance of Silence in the Resolution of Conflict: Western & Non Western Cultures" (College of Law, GSU, 1994)

- "Child Custody Concerns of Sentenced Mothers in Georgia" (a research project commissioned by the Division of Women's Services, Georgia Department of Corrections)

In 2004, Hampton published DeLeaver's biographical essay on Charles Alston in the Hampton University Museum of Fine Arts' International Review of African American Art.

Her most notable book is "Out From the Clusters." It is a monogram of the role of urban counselors. Copies of the book were distributed to every member of Congress and to the mayors in every city with a population over 50,000 as part of a book series review on the "Negro."

- Pierce, Lemoine D; Greene, Stilson. Billy Pierce: dance master, son of Purcellville. Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. OCLC 229161861.

- Pierce, Lemoine D; Greene, Stilson. George Washington Carver: scientist, artist & musician (a monograph prepared for the Black History Committee of Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. Friends of the Thomas Balch Library. OCLC 84907708. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- Pierce, Lemoine D. A research guide to the life and legislative achievements of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. OCLC 47194589. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

Organizations and recognition

DeLeaver became a member of the Phi Delta Kappa sorority in 1957. She joined the Teacher's Retirement System of the City of New York on September 22, 1959. She was a member of the Biglow Society, an honorary organization recognizing the generosity of individuals during their lifetime. DeLeaver went on to receive the Keller School of Graduate Management Certificate for Excellence in Teaching in 1998 and 1999.

She has served on the Boards of: the New York City Mission Society; The West Side Planned Parenthood Association; The Harlem Prep School; and Presbyterian Life Magazine, the national publication of the United Presbyterian Church.

In 1994, DeLeaver received the President's Award for Outstanding Contributions in the Field of Dispute Resolution from the International Society of Professionals in Dispute Resolution.

She was the founding director of the Family Mediation Association of Georgia.

Personal life

Lemoine DeLeaver tended to go by the nickname "Lee."

In 1961, she filed for divorce from her first husband Mr. Pierce in Mexico. At the time, the only grounds for divorce in New York was adultery. Since that was not the case and DeLeaver was on a "tight budget" she took a Greyhound bus to El Paso, Texas, which was in walking distance to a Mexican town. In September 1964, she was having issues regarding child support from Mr. Pierce as recorded by a probation officer, Dorthy Brenton, writing to the then, Mrs. Lee Callender. Deleaver and Pierce had two children together, William and Leslie.

Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce married Dr. Eugene Callender on April 14, 1963, in New York, New York. On Saturday, June 27, 1970, New York Amsterdam News announced a column entitled, "Callenders Split; She Moves Out." In the column, DeLeaver Pierce told Amsterdam News, "it was because of gross incompatibility... an accumulation of many irreconcilable differences."

Their separation agreement was filed January 8, 1974, followed by a file for divorce on August 15 and a divorce judgement March 31, 1975. DeLeaver made no request for financial support because she was employed at Barnard College during their marriage and continued to work after they separated. She left the marriage with her two children William (15) and Leslie (13).

References

| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- "Collection: Lemoine DeLeaver Pierce papers | Archives Research Center". findingaids.auctr.edu. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library. hdl:20.500.12322/fa:082. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "National Conference Features Women of Atlanta". The Atlanta Voice. 12 August 1995. p. 12.

- Picker, Bennett G. (2003). Mediation Practice Guide: A Handbook for Resolving Business Disputes. American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-59031-169-1. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- Pierce, Lemoine D (2004). "Charles Alston: an appreciation". International Review of African American Art. 19 (4): 28–41. ISSN 1045-0920. OCLC 61750591. Retrieved 5 May 2021.