| Tripolitanian civil war | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

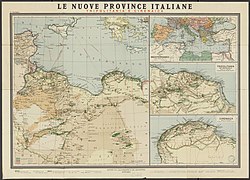

Map of Tunis and Tripoli. | |||||||

| |||||||

|

1790-1793 |

1790-1793 | ||||||

|

1793-1795 |

1793-1795 | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Tripolitanian civil war was a conflict from 1790 to 1795 which occurred in Tripolitania – inside what is today the country of Libya. It involved a war of succession between leading members of the Karamanli dynasty, an intervention by Ottoman officer Ali Burghul who claimed to be acting on the sultan's orders and controlled Tripoli for 17 months, and an intervention by the bey of Tunis Hammuda ibn Ali to restore the Karamanlis to power.

Background

Rise of the Karamanli

The 29 July 1711 Karamanli coup brought Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli into power as the bey of Ottoman Tripolitania, founding the Karamanli dynasty. Two Ottoman expeditions seeking to reclaim Tripolania under direct control of the Porte were sent, but Ahmad repulsed them. However, he expressed loyalty to the Ottoman sultan, sent him gifts and a delegation to Istanbul to re-establish relations, which paid off: in 1722, Ottoman sultan Ahmed III recognised Ahmed Karamanli's rule by bestowing the title of Pasha upon him. When Ahmed Karamanli died on 4 November 1745, his son Mehmed was governor (1745–1754), and after that his son 'Ali ibn Mehmed (1754–1793, also called 'Ali Pasha in some sources).

Looming succession crisis

Dynastic conflicts started in the 1780s, when 'Ali ibn Mehmed neglected affairs of state for 'an indolent life of pleasure'. As there were no well-established government institutions running daily state affairs in Tripolitania at the time, only a ruler's ability to directly assert his authority could secure political stability, which 'Ali did not. The Barbary corsairs, who had provided him with much revenue, got out of control in his absence, and their crimes led to unrest amongst the capital's population. 'Ali had promoted his eldest son Hasan to the position of bey and delegated most affairs of state to him, which enabled Hasan to accumulate power and secure the succession, to the jealousy of his similarly ambitious youngest brother Yusuf. In late 1787, 'Ali ibn Mehmed fell seriously ill, and both Hasan and Yusuf formed armed factions and readied themselves to seize power by force; but 'Ali recovered, and the looming succession crisis was postponed. The Fezzan-based Sayf Al Nasr clan exploited the power struggle by rebelling in 1788; Hasan could only barely repulse their attack on the capital, and only with the help of other tribal groups. Ottoman schemes for an amphibious campaign led by admiral Hasan Pasha of Algiers to retake all the semi-independent on the Mediterranean coast, including Karamanli Tripolitania, were abandoned when the sudden death of sultan Abdul Hamid I in April 1789 also resulted in a power struggle in Istanbul.

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

War

Yusuf's rebellion

In July 1790, 'Ali's youngest son Yusuf assassinated 'Ali's eldest son and designated successor Hasan Bey, luring him unarmed into their mother's quarters on the pretext of reconciliation. The population of Tripoli was outraged by this cowardly act, and an armed rebellion forced Yusuf and his supporters to flee to Manshiyya before they could consolidate their power. 'Ali's middle son Ahmad (Hamet Karamanli) was then promoted to bey, which Yusuf initially recognised in an attempt to restore his blemished reputation, but in June 1791 he declared open rebellion against his father and brother, and besieged Tripoli. Chérif (2010) described the period of 1791 to 1793 as a 'civil war', 'pitting various members of the Karamanli family against each other.' Yusuf claimed the throne for himself and was supported by the Arabs. In 1792–1793, he had himself proclaimed governor. Notables of Tripoli and some army commanders requested the Ottoman sultan to intervene in the conflict.

Usurpation or restoration?

At some point, the Ottoman officer Ali Burghul entered the conflict, although his exact role and relationship to the Sublime Porte was unclear. Burghul was a slave in Algiers before rising through the ranks. He had been Captain of the Marines (Wakil al-Kharj) in Algiers before the dey of Algiers, Sidi Hassan, dismissed him for insubordination in October 1791. Hassan did allow him to travel to Turkey by ship and take all his wealth along. A few months before Ali Burghul arrived in Istanbul, Yusuf started his open rebellion against his father and brother, and besieged Tripoli in June 1793. The Porte was informed of Yusuf's revolt, and worried that European powers, particularly France, would militarily interfere in Tripolitania; Ali Burghul sought to exploit this situation. Scholar Abun-Nasr (1987) stated: 'Shortly after arriving in Istanbul, secured the Ottoman government's approval for his invasion of Tripolitania without any help from the empire with the understanding that he would rule it in the name of the sultan. (...) His position in the Ottoman administration was uncertain, yet he claimed that he had been duly appointed pasha of Tripoli by the sultan.' Some authors such as Panzac (2005) describe him as 'an Algerian usurper who claimed to be supported by the sultan', rejecting the idea that Burghul was a legitimate representative of the Ottoman government of Tripolitania. Chérif (2010) characterised him as a 'Turkish official' sent by 'Istanbul' to 'retake effective control of Tripoli.'

Ali Burghul's intervention

On 29 July 1793, Burghul entered Tripolitania with a fleet of nine merchant ships carrying 300 mercenaries, mostly Turkish, Greek, and Spanish. He expelled 'Ali ibn Mehmed Karamanli on 30 July 1793; he fled to Tunis. With the support of some locals, Burghul defeated the guards of Hamet, and declared the reincorporation of Tripolitania into the Ottoman Empire, and himself the legitimate Pasha of Tripoli. He then proceeded to loot Tripoli, which caused a rebellion in the city.

The bey of Tunis, Hammuda ibn Ali, received the Karamanlis well, but because Burghul claimed to act on the sultan's authority, Hammuda hesitated to take action against him. This changed when Burghul occupied Djerba (Jirba), an island under Hammuda's jurisdiction, on 30 September 1794.

On 19 January 1795, Hamet and his brother Yusuf returned to Tripoli with the aid of the Bey of Tunis and the rebels, and took control of the throne. Burghul fled to Egypt. 'Ali ibn Mehmed renounced the governorship of Tripoli in favour of his son Hamet.

Aftermath

Following the end of the war, Hamet Karamanli was initially returned to the throne, ruling again as Ahmad II Pasha from 20 January 1795 until 11 June 1795, when his brother Yusuf deposed him, seized the throne, and sent Hamet into exile. Hamet fled to Malta, while Yusuf had himself proclaimed governor of Tripolitania in November 1796. In 1797, Yusuf's position was confirmed by the sultan's firman (order, or official document) of investiture.

Hamet later tried unsuccessfully to return and seize the throne with American support in the Battle of Derna during the First Barbary War (1801–1805), but a plan to proclaim him as Ahmad Bey the Governor of Cyrenaica was prevented by the English, who mediated a treaty.

References

- ^ Lea, David; Rowe, Annamarie (2003). A Political Chronology of Africa. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 9781135356668. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 193.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 194.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 194–195.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 195.

- ^ Chérif, M. H. (2010). História Geral da África – Vol. V – África do século XVI ao XVIII (in Portuguese). Brasília: UNESCO. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9788576521273. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 196.

- ^ Panzac, Daniel (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800–1820. Leiden: Brill. p. 13. ISBN 9789004125940. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ʻAbd al-Raḥmān Jabartī (1994). Abd Al-Rahmann Al-Jabarti's History of Egypt. Franz Steiner.

- St John, Ronald Bruce (2002). Libya and the United States: two centuries of strife. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8122-3672-6. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

Literature

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil Mir'i (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337670. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Civil wars in Libya

- Wars involving the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Tripolitania

- Civil wars of the Early Modern period

- Conflicts in 1793

- Conflicts in 1794

- Conflicts in 1795

- 1793 in Africa

- 1793 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1794 in Africa

- 1794 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1795 in Africa

- 1795 in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th century in Libya

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Africa