Lode coordinates or Haigh–Westergaard coordinates . are a set of tensor invariants that span the space of real, symmetric, second-order, 3-dimensional tensors and are isomorphic with respect to principal stress space. This right-handed orthogonal coordinate system is named in honor of the German scientist Dr. Walter Lode because of his seminal paper written in 1926 describing the effect of the middle principal stress on metal plasticity. Other examples of sets of tensor invariants are the set of principal stresses or the set of kinematic invariants . The Lode coordinate system can be described as a cylindrical coordinate system within principal stress space with a coincident origin and the z-axis parallel to the vector .

Mechanics invariants

The Lode coordinates are most easily computed using the mechanics invariants. These invariants are a mixture of the invariants of the Cauchy stress tensor, , and the stress deviator, , and are given by

which can be written equivalently in Einstein notation

where is the Levi-Civita symbol (or permutation symbol) and the last two forms for are equivalent because is symmetric ().

The gradients of these invariants can be calculated by

where is the second-order identity tensor and is called the Hill tensor.

Axial coordinate

The -coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the orthogonal projection of the stress state onto the hydrostatic axis.

where

is the unit normal in the direction of the hydrostatic axis.

Radial coordinate

The -coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the stress deviator (the orthogonal projection of the stress state into the deviatoric plane).

where

Derivation The relation that can be found by expanding the relation and writing in terms of the isotropic and deviatoric parts while expanding the magnitude of

- .

Because is isotropic and is deviatoric, their product is zero. Which leaves us with

Applying the identity and using the definition of

is a unit tensor in the direction of the radial component.

Lode angle – angular coordinate

The Lode angle can be considered, rather loosely, a measure of loading type. The Lode angle varies with respect to the middle eigenvalue of the stress. There are many definitions of Lode angle that each utilize different trigonometric functions: the positive sine, negative sine, and positive cosine (here denoted , , and , respectively)

and are related by

Derivation The relation between and can be shown by applying a trigonometric identity relating sine and cosine by a shift - .

Because cosine is an even function and the range of the inverse cosine is usually we take the negative possible value for the term, thus ensuring that is positive.

These definitions are all defined for a range of .

| Stress State | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| range | ||||

| Triaxial Compression (TXC) | ||||

| Shear (SHR) | ||||

| Triaxial Extension (TXE) |

The unit normal in the angular direction which completes the orthonormal basis can be calculated for and using

- .

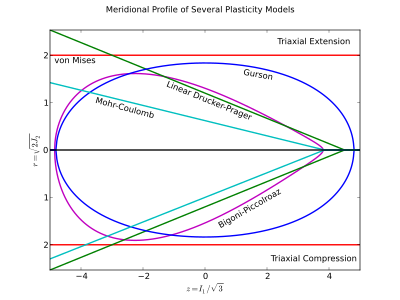

Meridional profile

The meridional profile is a 2D plot of holding constant and is sometimes plotted using scalar multiples of . It is commonly used to demonstrate the pressure dependence of a yield surface or the pressure-shear trajectory of a stress path. Because is non-negative the plot usually omits the negative portion of the -axis, but can be included to illustrate effects at opposing Lode angles (usually triaxial extension and triaxial compression).

One of the benefits of plotting the meridional profile with is that it is a geometrically accurate depiction of the yield surface. If a non-isomorphic pair is used for the meridional profile then the normal to the yield surface will not appear normal in the meridional profile. Any pair of coordinates that differ from by constant multiples of equal absolute value are also isomorphic with respect to principal stress space. As an example, pressure and the Von Mises stress are not an isomorphic coordinate pair and, therefore, distort the yield surface because

and, finally, .

Octahedral profile

The octahedral profile is a 2D plot of holding constant. Plotting the yield surface in the octahedral plane demonstrates the level of Lode angle dependence. The octahedral plane is sometimes referred to as the 'pi plane' or 'deviatoric plane'.

The octahedral profile is not necessarily constant for different values of pressure with the notable exceptions of the von Mises yield criterion and the Tresca yield criterion which are constant for all values of pressure.

A note on terminology

The term Haigh-Westergaard space is ambiguously used in the literature to mean both the Cartesian principal stress space and the cylindrical Lode coordinate space

See also

- Yield (engineering)

- Plasticity (physics)

- Stress

- Henri Tresca

- von Mises stress

- Mohr–Coulomb theory

- Strain

- Strain tensor

- Stress–energy tensor

- Stress concentration

- 3-D elasticity

References

- Menetrey, Philippe; Willam, K. J.; 1995, "Triaxial Failure Criterion for Concrete and its Generalization", Structural Journal, American Concrete Institute, Volume 92, Issue 3, pages 311-318, DOI: 10.14359/1132

- Lode, Walter (1926), „Versuche über den Einfluß der mittleren Hauptspannung auf das Fließen der Metalle Eisen, Kupfer und Nickel“ , Zeitschrift für Physik, vol. 36 (November), pp. 913–939, DOI: 10.1007/BF01400222

- Asaro, Robert J.; Lubarda, Vlado A.; 2006, Mechanics of Solids and Materials, Cambridge University Press

- Brannon, Rebecca M.; 2009, KAYENTA: Theory and User's Guide, Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- Chakrabarty, Jagabanduhu; 2006, Theory of Plasticity: Third edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- de Souza Neto, Eduardo A.; Peric, Djordje; Owen, David R. J.; 2008, Computational Methods for Plasticity: Theory and Applications, Wiley

- Han, D. J.; Chen, Wai-Fah; 1985, "A Nonuniform Hardening Plasticity Model for Concrete Materials", Mechanics of Materials, Volume 4, Issues 3–4, December 1985, Pages 283-302, doi: 10.1016/0167-6636(85)90025-0

- ^ Brannon, Rebecca M.; 2007, Elements of Phenomenological Plasticity: Geometrical Insight, Computational Algorithms, and Topics in Shock Physics, Shock Wave Science and Technology Reference Library: Solids I, Springer-New York

- Bigoni, Davide; Piccolroaz, Andrea; 2004, "Yield criteria for quasibrittle and frictional materials", International Journal of Solids and Structures, Volume 41, Issues 11–12, June 2004, Pages 2855-2878, doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2003.12.024

- Lubliner, Jacob; 1990, Plasticity Theory, Pearson Education

- Chaboche, J.-L.; 2008, "A review of some plasticity and viscoplasticity theories", International Journal of Plasticity, 24(10):1642-1693, DOI:10.1016/j.ijplas.2008.03.009

- Mouazen, Abdul Mounem; Neményi, Miklós; 1998, "A review of the finite element modelling techniques of soil tillage", Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, Volume 48, Issue 1, 1 November 1998, Pages 23-32, doi: 10.1016/S0378-4754(98)00152-9

- Keryvin, Vincent; 2008, "Indentation as a probe for pressure sensitivity of metallic glasses", Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, Volume 20, Number 11, DOI: 10.1088/0953-8984/20/11/114119

- Červenka, Jan; Papanikolaou, Vassilis K.; 2008, "Three dimensional combined fracture–plastic material model for concrete", International Journal of Plasticity, Volume 24, Issue 12, December 2008, Pages 2192-2220, doi: 10.1016/j.ijplas.2008.01.004

- Piccolroaz, Andrea; Bigoni, Davide; 2009, "Yield criteria for quasibrittle and frictional materials: A generalization to surfaces with corners", International Journal of Solids and Structures, Volume 46, Issue 20, 1 October 2009, Pages 3587-3596, doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2009.06.006

,

,  ,

,  are constant. Plotted in principal stress space. The red plane represents a meridional plane and the yellow plane an octahedral plane.

are constant. Plotted in principal stress space. The red plane represents a meridional plane and the yellow plane an octahedral plane. or Haigh–Westergaard coordinates

or Haigh–Westergaard coordinates  . are a set of

. are a set of  or the set of kinematic invariants

or the set of kinematic invariants  . The Lode coordinate system can be described as a

. The Lode coordinate system can be described as a  .

.

, and the

, and the  , and are given by

, and are given by

is the

is the  are equivalent because

are equivalent because  ).

).

is the second-order identity tensor and

is the second-order identity tensor and  is called the Hill tensor.

is called the Hill tensor.

-coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the

-coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the

-coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the stress deviator (the

-coordinate is found by calculating the magnitude of the stress deviator (the

can be found by expanding the relation

can be found by expanding the relation

in terms of the isotropic and deviatoric parts while expanding the magnitude of

in terms of the isotropic and deviatoric parts while expanding the magnitude of  .

. is isotropic and

is isotropic and

and using the definition of

and using the definition of

with respect to the low and high principal stresses.

with respect to the low and high principal stresses. ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively)

, respectively)

.

. we take the negative possible value for the

we take the negative possible value for the

.

.

.

. holding

holding  and the

and the  are not an isomorphic coordinate pair and, therefore, distort the yield surface because

are not an isomorphic coordinate pair and, therefore, distort the yield surface because

.

.

holding

holding