María Dolores Estévez Zuleta (1906–1959), commonly known as Lola la Chata, was the first major female drug trafficker dealing marijuana, morphine and heroin in Mexico from the 1930s to 1950s. She became well known due to tabloid newspaper coverage. She was a predecessor of today’s drug trafficking culture in the country.

Estévez went from being a local dealer to an international trafficker at a time when the drug trade was becoming more sophisticated. She sold her merchandise both outside and inside of prison for almost thirty years, contributing to a crisis in relations between the governments of Mexico and the United States. Efforts against her included a Mexican presidential decree, but she avoided a life sentence and continued her activities.

Childhood and introduction to the drug trade

Known as one of the first female drug traffickers in Mexico, La Chata began as a vendor of fried pork skin (cracklings or “chicharrones”) in the La Merced barrio of Mexico City, where she grew up. During her childhood this neighborhood was growing with a large influx of immigrants from various parts of Mexico, which increased the area’s formal and informal commercial activity. As a child she worked at her mother’s stand selling chicharrones and coffee. When she was thirteen, she began selling marijuana and morphine from this stand. Soon after she worked as a “mule” selling drugs on the streets of the city, using common baskets to hide the merchandise.

Through this activity, she met Castro Ruiz Urquizo of Ciudad Juárez, accompanying him there and learned about the international drug trade, making connections with some of the more prominent families in this activity living along the US-Mexico border. Living in the north, she had two daughters, María Luisa y Dolora, both of whom also later became involved in drug trafficking, making her a matriarch.

After she returned to Mexico City, La Chata opened her own stand selling food in La Merced. However, she used this business as a cover to continue selling marijuana, morphine and heroin through the 1920s.

Rise

By the end of the 1930s, Estévez’s activities came to the attention of the governments of both Mexico and the United States as one of those most responsible for the growth of the drug trade in Mexico City. Her network extended from that city into the United States and even into Canada, constructed from family and romantic connections, the only ones available to women of that time period. She married a former cop named Enrique Jaramillo and converted a mechanics’ shop in Pachuca into a distribution center. Her marriage gave her contacts in the police and the political class, which provided her information and a means of money laundering. Another of her known accomplices was Enrique Escudero Romano. Her relationship with him and other men allowed her to continue expanding her business beyond Mexico City. Jaramillo was her principal point person in Mexico City and Escudero helped her maintain contacts and laboratories outside the city.

Although the rise in drug trafficking was becoming more problematic for North American governments in the 1920s and 1930s, Estévez’s prominence in the trade made her seem more dangerous to drug control efforts because she was a woman. The narrative of anti-drug efforts was that it made women victims. However, La Chata was not a passive participant, but rather an opportunist.

Prosecution of La Chata

The secretary of public health under President Lázaro Cárdenas, Dr. Leopoldo Salazar Viniegra, began a campaign in the late 1930s to understand drug use from a medical perspective, especially that of marijuana. The goal was to see the user as having a medical condition but the seller as the real criminal. Salazar became one of the main prosecutors of Estévez. In 1938, he wrote a public letter in which he stated that she was ugly, in contrast to government-promoted stereotypes of females in the drug trade as being sexual seductresses. However, the same letter also recognized La Chata’s ability to know her clients and their needs, as well as those who she bribed to extend her power up to the highest circles of Mexican society. The objective of the letter was to portray Estévez as a woman only concerned about her business and not about Mexico’s desire to move forward.

She was arrested seven times between 1934 and 1945, imprisoned in Lecumberri, the Women’s Prison in Mexico City and even at Islas Marías in the Pacific Ocean. During these stints, she managed to keep a comfortable lifestyle, with servants and even a hairstylist to visit her in prison from time to time. She received many visitors looking for advice or help and was allowed conjugal visits and private visits with her daughters. She even had a hotel and airstrip constructed on the Islas Marías to make the trip easier for her daughters.

During the 1938 arrest, Captain Luis Huesca de la Fuente, former chief of the narcotics division of the Department of Public Health, was also arrested, accused of returning confiscated drugs to market as well as protecting traffickers, including La Chata.

In 1945, Mexican president Manuel Ávila Camacho issued a decree against drug traffickers, specifying La Chata, who was also highly wanted by the then head of the Bureau of Narcotics of the U.S Harry J. Anslinger and Canadian drug authorities. This extra attention came about from Estévez’s drug runs from Mexico to Canada using a 1942 Cadillac or a 1938 Dodge, but the 1945 arrest occurred in Mexico City. However, all three agencies provided evidence against her in court. She was sent to prison in the Islas Marías, but was transferred soon after to Mexico City for medical reasons. From there, she was still able to run her empire.

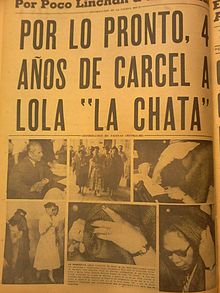

La Chata’s last arrest came in 1957, while she was processing heroin in her home. Newspaper accounts at the time noted her as “an internationally famous drug trafficker, “ captured with Luis Jaramillo and ten of her “agents.” Her mansion contained 29,000,000 pesos in cash (five million today), along with jewels, rifles and ammunition. She managed to keep her accomplices out of prison to assure the continuation of the business. After her sentencing, she was sent to the Women’s Prison in Mexico City, where she died in September 1959 from heart failure. It is rumored that the real cause was a heroin overdose, but her heart condition was well known. Despite her reputation, about 500 people attended her funeral, a third of which were former policemen.

Influence

Lola la Chata is considered to be one of the inspirations of American writer William S. Burroughs, who used her as a model for several characters, generally with the name of Lupe, Lupita or Lola. In Cities of the Red Night, Burroughs describes an encounter between the protagonist and La Chata, who provides him with heroin.

References

- ^ Carey, Elainev (2009). ""Selling is More of a Habit than Using" Narcotraficante Lola la Chata and Her Threat to Civilization, 1930-1960" (PDF). Journal of Women's History. 21 (2): 62–89. doi:10.1353/jowh.0.0080. S2CID 143336299. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Castillo Berthler, Héctor (August 24, 2006). "La Merced y el comercio mayorista" [La Merced and wholesale commerce] (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Lomnitz, Claudio (2000). Vicios públicos, virtudes privadas: la corrupción en México [Public vices, private virtues: Corruption in Mexico] (in Spanish). CIESAS. ISBN 9789707010505.

- ^ "La Chata, la primera gran narco mexicana" [La Chata, the first great Mexican narco]. Notimex México (in Spanish). January 12, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Todo Personal, La Chata, la primera narco mexicana. Mexico City: Proyecto 40. Retrieved April 23, 2013.