Louis Weiss (December 21, 1890 – December 14, 1963, Los Angeles) was an American independent producer of low-budget comedies, westerns, serials, and exploitation films.

Early life

Louis Weiss was born in New York City and left school after third grade (elementary school), according to the 1940 US census. In 1907 he established a nickelodeon theater, launching a lifelong enthusiasm for motion pictures. In the 1920s he joined with his brothers Adolph and Max to form the Weiss Brothers production company, with money earned from a New York lamp-and-fixture store, phonograph sales, and ownership of a theater that developed into a small chain.

Silent films

Most of the Weiss productions were never reviewed or copyrighted, apparently deliberately avoiding press attention. The only record of their existence is found in an occasional release chart, a few advertisements and surviving prints. Though most Poverty Row producers averaged a six-reel length, or about 60 minutes, Weiss continually tried to pare that down to five reels, lasting just over 50 minutes.

Like other smaller studios, the Weiss Brothers tried to compete with big-studio movies whenever possible. One favorite ploy was making films based on popular fictional characters. An early success was The Adventures of Tarzan (1921), a 15-chapter serial notable for casting the original screen Tarzan, Elmo Lincoln. In 1925 Weiss released a series of one-reel adaptations of famous literary works, including The Scarlet Letter, Macbeth, A Tale of Two Cities, Vanity Fair, Oliver Twist (as Fagin), and A Christmas Carol (as Scrooge).

The mid-1920s marked a period of ambition and expansion for the Weiss Brothers. They added new short-subject series with comic characters Hairbreadth Harry (played by Earl Montgomery); Winnie Winkle (played by Ethelyn Gibson); and Izzie and Lizzie (played by Georgie Chapman and Bess True). In May 1926 Weiss signed former Hal Roach star Snub Pollard for a series of short comedies. These started as solo vehicles for Pollard, but soon devolved into imitations of the then-new comedy team of Laurel and Hardy, with Pollard in the sad-faced Laurel role and Marvin Loback as an approximation of Hardy; Pollard was always billed as the solo star. The Pollard shorts, although filmed on low budgets, were popular enough to continue into 1929, and they boosted the Weiss Brothers' standing among comedy producers. Weiss then signed a major star, the cross-eyed Mack Sennett comic Ben Turpin, to star in two-reel comedies; then hired circus acrobat Poodles Hanneford for a series of shorts. These films were all released to theaters under the Artclass trademark ("The Sign of a Good Picture").

The Weiss Brothers' advancing progress of the late 1920s came to a screeching halt with the coming of sound to motion pictures, and the stock market crash of 1929. The silent Weiss product had been cheap to begin with—much of it photographed outdoors to avoid building sets—and sound would only add to the expense. Louis Weiss, not having access to any soundstages in Hollywood, made a deal with Lee de Forest to make talking short subjects at de Forest's small Phonofilm studio in New York. Three were completed (including two Snub Pollard comedies, without Loback) when much of the brothers' producing capital was wiped out by Wall Street. The Weiss Brothers suspended production indefinitely and canceled all contracts. Now they could only afford to release occasional films themselves—including a "sound" reissue of the 1925 reel Scrooge with synchronized music—and would acquire the already completed films of other shoestring producers.

Serials

The Weiss Brothers' fortunes took an upturn when they entered the field of adventure serials in 1935. Under the corporate name of Stage and Screen Productions, the brothers announced three promising cliffhangers: Custer's Last Stand (relying heavily on footage from the Weiss Brothers' silent Custer's Last Fight), The Clutching Hand, and The Black Coin. The Custer serial attracted the most attention, being the brothers' initial serial effort, but all three serials did well on the independent market. The first three chapters of Custer's Last Stand were combined into a feature film as well. Film archivist Kit Parker, who handles the Weiss Brothers library for home video, notes that the Weiss salary scale for these serials was incredibly low: female lead Ruth Mix was paid only $3.75 per day.

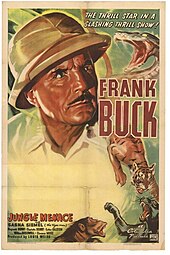

When Columbia Pictures decided to enter the serial field in 1937, the studio found it quicker and easier to hire a serial unit that was already functioning. Thus the Weiss Brothers found themselves now making serials for Columbia release. That year's three Weiss serials were Jungle Menace starring big-game hunter Frank Buck; The Mysterious Pilot with flying ace Frank Hawks; and The Secret of Treasure Island with Columbia's action star Don Terry. The Weiss serials were very successful, attracting more than the typical number of juvenile audiences for their 15 weekly chapters, and establishing Columbia as a worthy competitor in the serial field. Columbia then took over serial production itself, where it would remain active through the death of the form in 1956. The Weiss Brothers returned to the lower ranks of independent productions.

Exploitation films

Through the 1940s and into the 1950s, Louis Weiss and his son Adrian Weiss specialized in exploitation fare: cheap thrills for undemanding audiences. Their usual choice of director was Harry Fraser, a silent-era veteran who was noted for making his films look more elaborate than their low budgets allowed. Louis Weiss urgently needed a first-run "gorilla picture" when theaters couldn't get many new films, owing to a shortage of film stock. Fraser wrote and directed The White Gorilla (1945), which he frankly admitted was pure hokum. True to the Weiss tradition of cutting costs, half of the action was taken from Fraser's 1927 Artclass silent serial Perils of the Jungle, and the new footage with Ray Corrigan (playing both the leading role and the white gorilla) was filmed in four days on a standing jungle set. The White Gorilla, as Fraser recalled in his memoirs, "played in movie theaters across the country, making a bundle for several years, for the Louis Weiss company and for Harry Fraser, who got his cut regularly. It was a stinker of a picture, but it made money, Which only goes to prove that P. T. Barnum was right." The film was Louis Weiss's final theatrical feature. Adrian Weiss continued as an independent producer.

Final years

The Weiss production company was among the first to make its film library available to television; its silent comedies were first revived in 1947. Returning to their story property from the 1934 serial The Clutching Hand, Louis and Adrian Weiss produced the early TV series Craig Kennedy, Criminologist, starring veteran screen actor Donald Woods. The Weiss company discontinued further production and managed its film library for the rest of its existence.

In 1971 Adrian Weiss and his son Steven reorganized the company as Weiss Global Enterprises, handling its own productions as well as the independent features of Robert L. Lippert and the British-based library of Exclusive Films. The appeal of these films was comparatively limited but Weiss's broadcast fees were also comparatively low, making the films feasible for budget-restricted UHF TV stations. Archivist Kit Parker, after extensive negotiations with the Weiss family, bought the film library in 2004.

References

- Tino Balio. Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939 (History of the American Cinema, No. 5), University of California Press (January 29, 1996), p. 327.

- Motion Picture News, May 22, 1925, pp. 1988-1989.

- Film Daily, "Weiss Bros. Plan Several Talker Series in East", June 26, 1929, p. 2.

- Kit Parker. Weiss Bros. – Artclass and Beyond – The Sound Era, Nov. 17, 2012.

- Brian Taves, Studio Metamorphosis: Columbia's Emergence from Poverty Row, in Frank Capra, Culture and the Moving Image by Robert Sklar. Temple University Press, March 30, 1998, p. 248.

- Scott MacGillivray, Laurel & Hardy: From the Forties Forward, Second Edition, iUniverse, 2009, p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4401-7237-3

- Harry L. Fraser, I Went That-a-Way, Scarecrow Press, 1990, pp. 129-131. ISBN 978-0-8108-2340-2

Bibliography

- Lehrer, Steven (2006). Bring 'Em Back Alive: The Best of Frank Buck. Texas Tech University press. p. 248. ISBN 0-89672-582-0.