Luigi Lucioni (born Giuseppe Luigi Carlo Benevenuto Lucioni; November 4, 1900 – July 22, 1988) was an Italian American painter known for his still lifes, landscapes, and portraits.

Early life

Early years and immigration to the United States

Luigi Lucioni was born on November 4, 1900, in Malnate, Italy, which lies in a mountainous region approximately 30 miles north of Milan, in the foothills of the Alps near the border between Italy and Switzerland. Lucioni's parents, Angelo and Maria Beati Lucioni, who were married in 1890, were from the nearby region of Castiglione Olona, as were Lucioni's grandparents. Lucioni had three older sisters: Angela (b. 1891), Alice (b. 1893) and Aurora (b. 1897), and the family lived in a two-room apartment with no gas, running water or a bathtub. As Lucioni's grandmother was upset by the "pagan" names given to his sisters, his parents named him Giuseppe Luigi Carlo Benevenuto Lucioni, naming him after three saints, in order to make amends with her. Lucioni, who was greatly influenced by his strict disciplinarian mother, called her "La Bella Beati", or a beautiful blonde woman. His father Angelo was a coppersmith, but was not a good businessman, and often did not follow through by collecting from his customers. As was customary, Lucioni wore skirts until he was six years old, and clearly remembered wearing pants for the first time during a church holiday in 1906. As a child, Lucioni came to adore the natural beauty of the hills and mountainsides when he explored the region between Malnate and the Swiss border, and showed an early interest in art, in particular drawing, possibly influenced by a cousin of his father's, who also harbored a talent for drawing. Lucioni's first classes were in geometrical drawing, and at age six, his talent caught the attention of his teacher, Miss Gadisco, a woman from Varese who had some artistic training herself, and who encouraged him to pursue drawing and etching as a career.

Members of the Lucionis extended family had emigrated to the Transvaal Colony in Africa and to South America, which was a favored destination of northern Italians at the time, and because of the poor economy of 1900s Italy. 40-year-old Angelo emigrated to New York City in 1906, and after establishing himself as a coppersmith and tinsmith, sent for the rest of the family. Maria, having heard about the "savages and Indians" in the United States, took Lucioni to Milan, his first time in a big city, where he was confirmed in the Duomo in order to protect his soul. On July 15, 1911, the family boarded the ship Duke of Genoa for the U.S. Despite traveling steerage, Lucioni recalled the trip as "really nice". After being quarantined for nine days in the sweltering August heat in New York Harbor with 350 other third class passengers due to a cholera report, the ship landed at 34th Street pier on August 9, and the family was transferred to Ellis Island. While being processed there, they had to have several injections, and the embarrassment of having to expose her derrière in front of strangers caused the very modest and sensitive Angela to nearly have a nervous breakdown. The family then moved in with Angelo in the apartment he rented on Christopher Street in Manhattan.

Maria, who had never lived in a large city, took an immediate dislike to living in New York, and threatened to return to Malnate if the family did not move to a smaller town. On the suggestion of an American that the family had met on the Duke of Genoa, the family moved to North Bergen, New Jersey, and then several more times before settling in 1929 at 403 New York Avenue in Union City, New Jersey. Lucioni spent four years learning English on the streets of his newly adopted country, and was not placed in first grade until age 11. His life as an American was initially difficult for him, as he endured some bigotry from neighborhood children who called him a "guinea wop". He was made to scrub the home's wooden floor on his hands and knees, and not permitted to go out and play until this task was completed, which he credited with instilling in him a sense of discipline that served him well in his artistic life.

Education and early career

Lucioni advanced through his grades and won an academic medal in 1916. After completing the eighth grade, he did not attend school until college. He did take drawing lessons for several years at a drawing school where he worked every night after his studies concluded, copying the plaster heads. He left the school after he refused to acknowledge an instructor's criticism of his perspective. At age 15, Lucioni entered a competition for admission to Cooper Union and was accepted, taking evening classes while working at a Brooklyn engraving company during the day. The school curriculum was divided into four years, in which he would study geometric shapes, then drawing heads, then antiquities and then finally, drawing from life. For painting, he studied under William de Leftwich Dodge. As Lucioni recalls it, Dodge was initially not interested in Lucioni's work, and made his feelings known, but was kind and gentle, and allowed Lucioni to visit his studio on West 9th Street, where Lucioni received sound criticism. Lucioni cites Dodge as an influence in his own realization that one's belief in oneself is the key to fully realize one's own artistic vision, and not the adoption of contemporary trends in art or catering to others' expectations, a theme that Lucioni would express in his career. At age 19, Lucioni entered New York City's National Academy of Design, where he was introduced to the medium of etching through his instructor in that discipline, William Auerbach-Levy. Lucioni attended school in the morning, and worked in the art department at Fairchild Publications, which published Women's Wear Daily. He also took composition classes at Cooper Union.

During this time Lucioni lived at home, where his father's $20 a week salary allowed Lucioni, who never felt poor, to buy a new suit each Easter, though he and Angelo never developed a strong rapport, due to their separation between 1906 and 1911, and the fact that Angelo never learned English. In 1922, Lucioni took his father to his first opera, Aida, but his father was indifferent, and never came to share Lucioni's passion for opera. When Maria died in 1922, a great loss for Lucioni, her domestic duties were taken over by Aurora and Alice. Though Lucioni was devoted to Alice, he never formed a very close relationship with Angela, due to the differences in their ages. Angela joined a convent for some period of time, but left due to poor health, dying in 1926 at the age of 34. Lucioni, Alice and Aurora lived in a town house at 33 West 10th Street in New York during the winters, and at a farmhouse in Manchester, Vermont in the summer. Aurora died in 1981 and Alice in 1983.

Career

Lucioni's work was marketed through Associated American Artists in New York.

Lucioni's portrait of Paul Cadmus was included in the Brooklyn Museum's show "Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties" (winter 2010–2011) and was reproduced for the show's poster.

In 1938, Lucioni met Ethel Waters through their mutual friend, Carl Van Vechten. After several months, Lucioni asked Waters if he could paint her portrait and she readily agreed so a sitting was arranged at his studio on Washington Square. Waters bought the finished portrait from Lucioni in 1939 for $500. Waters was at the height of her career in 1939, at that time, she was the first African American to have a starring role on Broadway and was already a jazz and blues legend. In her portrait, Waters wears a beautifully tailored red dress with an elegant mink coat draped over the back of her chair. Not until one actually views this portrait in person can one feel the human emotion that Lucioni so deftly articulated on canvas. He positioned Waters with her arms tightly wrapped around her waist, a gesture that conveys a sense of vulnerability as if she were trying to protect herself. Intentional or not, this gesture is aptly symbolic of the challenges she faced as an impoverished African American woman growing up in a social climate of racial and gender discrimination.

In 2017, the Huntsville Museum of Art (HMA) acquired the historic Portrait of Ethel Waters. HMA Executive Director, Christopher J. Madkour, and Luigi Lucioni Historian, Dr. Stuart Embury, heard of the painting and were able to track down its whereabouts. The painting was thought to be lost since it had not been viewed by the public since 1942, but the two traced it to a private residence in 2016 and learned the family had plans to auction the painting off in the coming months. The owner graciously allowed the Huntsville Museum of Art to display Portrait of Ethel Waters in the exhibition, American Romantic: The Art of Luigi Lucioni, where it was viewed by the public for the first time in over 70 years. The museum successfully negotiated the purchase of Portrait of Ethel Waters and, thanks in large part to the generosity of the Huntsville community, Lucioni's Portrait of Ethel Waters now has a new home at the Huntsville Museum of Art in Huntsville, Alabama where it will be made accessible for public viewing.

-

Vermont Pastoral, etching, Lucioni, 1939, Dallas Museum of Art

Vermont Pastoral, etching, Lucioni, 1939, Dallas Museum of Art

-

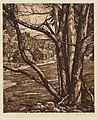

Tree Rhythm, etching, Lucioni, 1953, Dallas Museum of Art

Tree Rhythm, etching, Lucioni, 1953, Dallas Museum of Art

-

Hilltop Elms, etching, Lucioni, 1955, Dallas Museum of Art

Hilltop Elms, etching, Lucioni, 1955, Dallas Museum of Art

-

Contrasting Textures, oil, Lucioni, 1965, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Contrasting Textures, oil, Lucioni, 1965, Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Birches and Beyond, etching, Lucioni, 1973, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Birches and Beyond, etching, Lucioni, 1973, Smithsonian American Art Museum

References

- ^ Embury, Stuart P. (2006). "Chapter One: The Early Years". The Art and Life of Luigi Lucioni. Embury Publishing Company. pp. 1-4.

- "Associated American Artists Records". Syracuse University Libraries. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- "Exhibitions: Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Embury, Dr. Stuart (2018). Art and Soul - Luigi Lucioni and Ethel Waters: A Friendship. Huntsville, Alabama: Huntsville Museum of Art. pp. 3, 22.

External links

- "Luigi Lucioni (1900-1988)". Equinox Antiques.

- "Luigi Lucioni". artnet.

- Carbone, Terry (November 22, 2011). "Cover Guy: Paul Cadmus by Luigi Lucioni". Brooklyn Museum.

- "Pastoral Vermont: The Paintings and Etchings of Luigi Lucioni". Middlebury College Museum of Art.

- "Luigi Lucioni: American Painter, 1900-1988". ArtCyclopedia.

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- American printmakers

- 1900 births

- 1988 deaths

- Cooper Union alumni

- Italian gay artists

- American gay artists

- Italian LGBTQ painters

- American LGBTQ painters

- Gay painters

- People from Union City, New Jersey

- People from North Bergen, New Jersey

- People from the Province of Varese

- Italian emigrants to the United States

- Painters from New Jersey