| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Lute" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

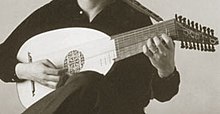

Renaissance lute in 2013 Renaissance lute in 2013 | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | String instrument (plucked) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321 (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed |

|

| Related instruments | |

| List | |

| Musicians | |

| List | |

| Builders | |

| List | |

A lute (/ljuːt/ or /luːt/) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" commonly refers to an instrument from the family of European lutes which were themselves influenced by Indian short-necked lutes in Gandhara which became the predecessor of the Islamic, the Sino-Japanese and the European lute families. The term also refers generally to any necked string instrument having the strings running in a plane parallel to the sound table (in the Hornbostel–Sachs system).

The strings are attached to pegs or posts at the end of the neck, which have some type of turning mechanism to enable the player to tighten the tension on the string or loosen the tension before playing (which respectively raise or lower the pitch of a string), so that each string is tuned to a specific pitch (or note). The lute is plucked or strummed with one hand while the other hand "frets" (presses down) the strings on the neck's fingerboard. By pressing the strings on different places of the fingerboard, the player can shorten or lengthen the part of the string that is vibrating, thus producing higher or lower pitches (notes).

The European lute and the modern Near-Eastern oud descend from a common ancestor via diverging evolutionary paths. The lute is used in a great variety of instrumental music from the Medieval to the late Baroque eras and was the most important instrument for secular music in the Renaissance. During the Baroque music era, the lute was used as one of the instruments that played the basso continuo accompaniment parts. It is also an accompanying instrument in vocal works. The lute player either improvises ("realizes") a chordal accompaniment based on the figured bass part, or plays a written-out accompaniment (both music notation and tablature ("tab") are used for lute). As a small instrument, the lute produces a relatively quiet sound. The player of a lute is called a lutenist, lutanist or lutist, and a maker of lutes (or any similar string instrument, or violin family instruments) is referred to as a luthier.

History and evolution of the lute

See also: Lyre and History of lute-family instrumentsFirst lutes

Ancient Egyptian tomb painting depicting players with long-necked lutes, 18th Dynasty (c. 1350 BC).

Ancient Egyptian tomb painting depicting players with long-necked lutes, 18th Dynasty (c. 1350 BC). Hellenistic banquet scene from 1st century A.D., Hadda, Gandhara. Lute player with short-necked lute, far right.

Hellenistic banquet scene from 1st century A.D., Hadda, Gandhara. Lute player with short-necked lute, far right.

Lute in Pakistan, Gandhara, probably Butkara in Swat, Kushan Period (1st century-320)

Lute in Pakistan, Gandhara, probably Butkara in Swat, Kushan Period (1st century-320) Gandhara Lute, Pakistan, Swat Valley, Gandhara region, 4th-5th century

Gandhara Lute, Pakistan, Swat Valley, Gandhara region, 4th-5th century

Curt Sachs defined lute in the terminology section of The History of Musical Instruments as "composed of a body, and of a neck which serves both as a handle and as a means of stretching the strings beyond the body". His definition focused on body and neck characteristics and not on the way the strings were sounded, so the fiddle counted as a "bowed lute". Sachs also distinguished between the "long-necked lute" and the short-necked variety. The short-necked variety contained most of our modern instruments, "lutes, guitars, hurdy-gurdies and the entire family of viols and violins".

The long lutes were the more ancient lutes; the "Arabic tanbūr ... faithfully preserved the outer appearance of the ancient lutes of Babylonia and Egypt". He further categorized long lutes with a "pierced lute" and "long neck lute". The pierced lute had a neck made from a stick that pierced the body (as in the ancient Egyptian long-neck lutes, and the modern African gunbrī).

The long lute had an attached neck, and included the sitar, tanbur and tar: the dutār had two strings, setār three strings, čārtār four strings, pančtār five strings.

Sachs's book is from 1941, and the archaeological evidence available to him placed the early lutes at about 2000 BC. Discoveries since then have pushed the existence of the lute back to c. 3100 BC.

Musicologist Richard Dumbrill today uses the word lute more categorically to discuss instruments that existed millennia before the term "lute" was coined. Dumbrill documented more than 3,000 years of iconographic evidence of the lutes in Mesopotamia, in his book The Archaeomusicology of the Ancient Near East. According to Dumbrill, the lute family included instruments in Mesopotamia before 3000 BC. He points to a cylinder seal as evidence; dating from about 3100 BC or earlier and now in the possession of the British Museum, the seal depicts on one side what is thought to be a woman playing a stick "lute". Like Sachs, Dumbrill saw length as distinguishing lutes, dividing the Mesopotamian lutes into a long variety and a short. His book does not cover the shorter instruments that became the European lute, beyond showing examples of shorter lutes in the ancient world. He focuses on the longer lutes of Mesopotamia, various types of necked chordophones that developed throughout the ancient world: Indian (Gandhara and others), Greek, Egyptian (in the Middle Kingdom), Iranian (Elamite and others), Jewish/Israelite, Hittite, Roman, Bulgar, Turkic, Chinese, Armenian/Cilician cultures. He names among the long lutes, the pandura and the tanbur

The line of short-necked lutes was further developed to the east of Mesopotamia, in Bactria and Gandhara, into a short, almond-shaped lute. Curt Sachs talked about the depictions of Gandharan lutes in art, where they are presented in a mix of "Northwest Indian art" under "strong Greek influences". The short-necked lutes in these Gandhara artworks were "the venerable ancestor of the Islamic, the Sino-Japanese and the European lute families". He described the Gandhara lutes as having a "pear-shaped body tapering towards the short neck, a frontal stringholder, lateral pegs, and either four or five strings".

Persian barbat

(Left-two images) Oud-family instruments painted in the Cappella Palatina in Sicily, 12th century. Roger II of Sicily employed Muslim musicians in his court, and paintings show them playing a mixture of lute-like instruments, strung with 3, 4 and five courses of strings. (Right) 13th century A.D. image of an Oud, from the 12th century work Bayâd und Riyâd, a larger instrument than those in images at the Cappella Palatina

(Left-two images) Oud-family instruments painted in the Cappella Palatina in Sicily, 12th century. Roger II of Sicily employed Muslim musicians in his court, and paintings show them playing a mixture of lute-like instruments, strung with 3, 4 and five courses of strings. (Right) 13th century A.D. image of an Oud, from the 12th century work Bayâd und Riyâd, a larger instrument than those in images at the Cappella Palatina

Bactria and Gandhara became part of the Sasanian Empire (224–651). Under the Sasanians, a short almond-shaped lute from Bactria came to be called the barbat or barbud, which was developed into the later Islamic world's oud or ud. When the Moors conquered Andalusia in 711, they brought their ud or quitra along, into a country that had already known a lute tradition under the Romans, the pandura.

During the 8th and 9th centuries, many musicians and artists from across the Islamic world flocked to Iberia. Among them was Abu l-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi' (789–857), a prominent musician, who had trained under Ishaq al-Mawsili (d. 850) in Baghdad and was exiled to Andalusia before 833. He taught and has been credited with adding a fifth string to his oud and with establishing one of the first schools of music in Córdoba.

By the 11th century, Muslim Iberia had become a center for the manufacture of instruments. These goods spread gradually to Provence, influencing French troubadours and trouvères and eventually reaching the rest of Europe. While Europe developed the lute, the oud remained a central part of Arab music, and broader Ottoman music, undergoing a range of transformations.

Beside the introduction of the lute to Spain (Andalusia) by the Moors, another important point of transfer of the lute from Arabian to European culture was Sicily, where it was brought either by Byzantine or later by Muslim musicians. There were singer-lutenists at the court in Palermo after the Norman conquest of the island from the Muslims, and the lute is depicted extensively in the ceiling paintings in the Palermo's royal Cappella Palatina, dedicated by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily in 1140. His Hohenstaufen grandson Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (1194–1250) continued integrating Muslims into his court, including Moorish musicians. Frederick II made visits to the Lech valley and Bavaria between 1218 and 1237 with a "Moorish Sicilian retinue". By the 14th century, lutes had spread throughout Italy and, probably because of the cultural influence of the Hohenstaufen kings and emperor, based in Palermo, the lute had also made significant inroads into the German-speaking lands. By 1500, the valley and Füssen had several lute-making families, and in the next two centuries the area hosted "famous names of 16th and 17th century lutemaking".

Although the major entry of the short lute was in Western Europe, leading to a variety of lute styles, the short lute entered Europe in the East as well; as early as the sixth century, the Bulgars brought the short-necked variety of the instrument called komuz to the Balkans.

From Middle Ages to Baroque

Medieval lutes were four- and five-course instruments, plucked with a quill as a plectrum. There were several sizes and, by the end of the Renaissance, seven sizes (up to the great octave bass) are documented. Song accompaniment was probably the lute's primary function in the Middle Ages, but very little music securely attributable to the lute survives from before 1500. Medieval and early-Renaissance song accompaniments were probably mostly improvised, hence the lack of written records.

In the last few decades of the fifteenth century, to play Renaissance polyphony on a single instrument, lutenists gradually abandoned the quill in favor of plucking the instrument with the fingers. The number of courses grew to six and beyond. The lute was the premier solo instrument of the sixteenth century, but continued to accompany singers as well.

About 1500, many Iberian lutenists adopted vihuela de mano, a viol-shaped instrument tuned like the lute; both instruments continued in coexistence. This instrument also found its way to parts of Italy that were under Spanish domination (especially Sicily and the papal states under the Borgia pope Alexander VI who brought many Catalan musicians to Italy), where it was known as the viola da mano.

By the end of the Renaissance, the number of courses had grown to ten, and during the Baroque era the number continued to grow until it reached 14 (and occasionally as many as 19). These instruments, with up to 35 strings, required innovations in the structure of the lute. At the end of the lute's evolution the archlute, theorbo and torban had long extensions attached to the main tuning head to provide a greater resonating length for the bass strings, and since human fingers are not long enough to stop strings across a neck wide enough to hold 14 courses, the bass strings were placed outside the fretboard, and were played open, i.e., without pressing them against the fingerboard with the left hand. "The lute is a very fragile instrument and so, although there are many surviving old lutes, very few with their original soundboards are in playable condition," which makes the Rauwolf Lute so notable.

Over the course of the Baroque era, the lute was increasingly relegated to the continuo accompaniment, and was eventually superseded in that role by keyboard instruments. The lute almost fell out of use after 1800. Some sorts of lute were still used for some time in Germany, Sweden, and Ukraine.

Detail of painting The Virgin and Child, by Masaccio, 1426. Showing a medieval lute.

Detail of painting The Virgin and Child, by Masaccio, 1426. Showing a medieval lute. Caravaggio: The Lute Player, c. 1596

Caravaggio: The Lute Player, c. 1596 Peter Paul Rubens: Lute Player (1609–1610)

Peter Paul Rubens: Lute Player (1609–1610) Nicholas Lanier, 1613

Nicholas Lanier, 1613 Frans Hals: The Lute Player, 1623

Frans Hals: The Lute Player, 1623 Bernardo Strozzi: Lute Player, after 1640

Bernardo Strozzi: Lute Player, after 1640 Artist David Hoyer painted by Jan Kupetzky, c. 1711

Artist David Hoyer painted by Jan Kupetzky, c. 1711

Etymology

The words lute and oud possibly derive from Arabic al-ʿoud (العود - literally means "the wood"). It may refer to the wooden plectrum traditionally used for playing the oud, to the thin strips of wood used for the back, or to the wooden soundboard that distinguished it from similar instruments with skin-faced bodies.

Many theories have been proposed for the origin of the Arabic name. Music scholar Eckhard Neubauer suggested that oud may be an Arabic borrowing from the Persian word rōd or rūd, which meant string. Another researcher, archaeomusicologist Richard J. Dumbrill, suggests that rud came from the Sanskrit rudrī (रुद्री, meaning "string instrument") and transferred to Arabic and European languages by way of a Semitic language. However another theory, according to Semitic language scholars, is that the Arabic ʿoud is derived from Syriac ʿoud-a, meaning "wooden stick" and "burning wood"—cognate to Biblical Hebrew 'ūḏ, referring to a stick used to stir logs in a fire. Henry George Farmer notes the similarity between al-ʿūd and al-ʿawda ("the return" – of bliss).

Construction

Soundboard

Lutes are made almost entirely of wood. The soundboard is a teardrop-shaped thin flat plate of resonant wood (typically spruce). In all lutes the soundboard has a single (sometimes triple) decorated sound hole under the strings called the rose. The sound hole is not open, but rather covered with a grille in the form of an intertwining vine or a decorative knot, carved directly out of the wood of the soundboard.

The geometry of the lute soundboard is relatively complex, involving a system of barring that places braces perpendicular to the strings at specific lengths along the overall length of the belly, the ends of which are angled to abut the ribs on either side for structural reasons. Robert Lundberg, in his book Historical Lute Construction, suggests ancient builders placed bars according to whole-number ratios of the scale length and belly length. He further suggests the inward bend of the soundboard (the "belly scoop") is a deliberate adaptation by ancient builders to afford the lutenist's right hand more space between the strings and soundboard.

Soundboard thickness varies, but generally hovers between 1.5 and 2 mm (0.06–0.08 in). Some luthiers tune the belly as they build, removing mass and adapting bracing to produce desirable sonic results. The lute belly is almost never finished, but in some cases the luthier may size the top with a very thin coat of shellac or glair to help keep it clean. The belly joins directly to the rib, without a lining glued to the sides, and a cap and counter cap are glued to the inside and outside of the bottom end of the bowl to provide rigidity and increased gluing surface.

After joining the top to the sides, a half-binding is usually installed around the edge of the soundboard. The half-binding is approximately half the thickness of the soundboard and is usually made of a contrasting color wood. The rebate for the half-binding must be extremely precise to avoid compromising structural integrity.

Back

Lutes by Matthäus Büchenberg, 1613 (left) and by Matteo Sellas, 1641 in Museu de la Música de Barcelona

Lutes by Matthäus Büchenberg, 1613 (left) and by Matteo Sellas, 1641 in Museu de la Música de Barcelona Various lutes exhibited at the Deutsches Museum

Various lutes exhibited at the Deutsches Museum

The back or the shell is assembled from thin strips of hardwood (maple, cherry, ebony, rosewood, gran, wood and/or other tonewoods) called ribs, joined (with glue) edge to edge to form a deep rounded body for the instrument. There are braces inside on the soundboard to give it strength.

Neck

The neck is made of light wood, with a veneer of hardwood (usually ebony) to provide durability for the fretboard beneath the strings. Unlike most modern stringed instruments, the lute's fretboard is mounted flush with the top. The pegbox for lutes before the Baroque era was angled back from the neck at almost 90° (see image), presumably to help hold the low-tension strings firmly against the nut which, traditionally, is not glued in place but is held in place by string pressure only. The tuning pegs are simple pegs of hardwood, somewhat tapered, that are held in place by friction in holes drilled through the pegbox.

As with other instruments that use friction pegs, the wood for the pegs is crucial. As the wood suffers dimensional changes through age and loss of humidity, it must retain a reasonably circular cross-section to function properly—as there are no gears or other mechanical aids for tuning the instrument. Often pegs were made from suitable fruitwoods such as European pearwood, or equally dimensionally stable analogues. Matheson, c. 1720, said, "If a lute-player has lived eighty years, he has surely spent sixty years tuning."

Bridge

The bridge, sometimes made of a fruitwood, is attached to the soundboard typically between a fifth and a seventh of the belly length. It does not have a separate saddle but has holes bored into it to which the strings attach directly. The bridge is made so that it tapers in height and length, with the small end holding the trebles and the higher and wider end carrying the basses. Bridges are often colored black with carbon black in a binder, often shellac and often have inscribed decoration. The scrolls or other decoration on the ends of lute bridges are integral to the bridge, and are not added afterwards as on some Renaissance guitars (cf Joachim Tielke's guitars).

Frets

The frets are made of loops of gut tied around the neck. They fray with use, and must be replaced from time to time. A few additional partial frets of wood are usually glued to the body of the instrument, to allow stopping the highest-pitched courses up to a full octave higher than the open string, though these are considered anachronistic by some (though John Dowland and Thomas Robinson describe the practice of gluing wooden frets onto the soundboard). Given the choice between nylon and gut, many luthiers prefer to use gut, as it conforms more readily to the sharp angle at the edge of the fingerboard.

Strings

Strings were historically made of animal gut, usually from the small intestine of sheep (sometimes in combination with metal) and are still made of gut or a synthetic substitute, with metal windings on the lower-pitched strings. Modern manufacturers make both gut and nylon strings, and both are in common use. Gut is more authentic for playing period pieces, though unfortunately it is also more susceptible to irregularity and pitch instability owing to changes in humidity. Nylon offers greater tuning stability, but is seen as anachronistic by purists, as its timbre differs from the sound of earlier gut strings. Such concerns are moot when more recent compositions for the lute are performed.

Of note are the catlines used as basses on historical instruments. Catlines are several gut strings wound together and soaked in heavy metal solutions to increase the string mass. Catlines can be quite large in diameter compared to wound nylon strings of the same pitch. They produce a bass that differs somewhat in timbre from nylon basses.

The lute's strings are arranged in courses, of two strings each, though the highest-pitched course usually consists of only a single string, called the chanterelle. In later Baroque lutes, two upper courses are single. The courses are numbered sequentially, counting from the highest pitched, so that the chanterelle is the first course, the next pair of strings is the second course, etc. Thus an 8-course Renaissance lute usually has 15 strings, and a 13-course Baroque lute has 24.

The courses are tuned in unison for high and intermediate pitches, but for lower pitches one of the two strings is tuned an octave higher (the course where this split starts changed over the history of the lute). The two strings of a course are virtually always stopped and plucked together, as if a single string—but in rare cases, a piece requires that the two strings of a course be stopped or plucked separately. The tuning of a lute is a complicated issue, described in a section of its own below. The lute's design makes it extremely light for its size.

Lute in the modern world

The lute enjoyed a revival with the awakening of interest in historical music around 1900 and throughout the century. That revival was further boosted by the early music movement in the twentieth century. Important pioneers in lute revival were Julian Bream, Hans Neemann, Walter Gerwig, Suzanne Bloch and Diana Poulton. Lute performances are now not uncommon; there are many professional lutenists, especially in Europe where the most employment is found, and new compositions for the instrument are being produced by composers.

During the early days of the early music movement, many lutes were constructed by available luthiers, whose specialty was often classical guitars. Such lutes were heavily built with construction similar to that of classical guitars, with fan bracing, heavy tops, fixed frets, and lined sides, all of which are anachronistic to historical lutes. As lutherie scholarship increased, makers began constructing instruments based on historical models, which have proven lighter and more responsive instruments.

Lutes built at present are invariably replicas or near copies of those surviving historical instruments that are in museums or private collections. Many are custom-built, but there is a growing number of luthiers who build lutes for general sale, and there is a fairly strong, if small, second-hand market. Because of this fairly limited market, lutes are generally more expensive than mass-produced modern instruments. Factory-made guitars and violins, for example, can be purchased more cheaply than low-end lutes, while at the highest level of modern instruments, guitars and violins tend to command the higher prices.

Unlike in the past, there are many types of lutes encountered today: 5-course medieval lutes, renaissance lutes of 6 to 10 courses in many pitches for solo and ensemble performance of Renaissance works, the archlute of Baroque works, 11-course lutes in d-minor tuning for 17th-century French, German and Czech music, 13/14-course d-minor tuned German Baroque Lutes for later High Baroque and Classical music, theorbo for basso continuo parts in Baroque ensembles, gallichons/mandoras, bandoras, orpharions and others.

Lutenistic practice has reached considerable heights in recent years, thanks to a growing number of world-class lutenists: Rolf Lislevand, Hopkinson Smith, Paul O'Dette, Christopher Wilke, Andreas Martin, Robert Barto, Eduardo Egüez, Edin Karamazov, Nigel North, Christopher Wilson, Luca Pianca, Yasunori Imamura, Anthony Bailes, Peter Croton, Xavier Diaz-Latorre, Evangelina Mascardi and Jakob Lindberg. Singer-songwriter Sting has also played lute and archlute, in and out of his collaborations with Edin Karamazov, and Jan Akkerman released two albums of lute music in the 1970s while he was a guitarist in the Dutch rock band Focus. Lutenist/Composer Jozef van Wissem composed the soundtrack to the Jim Jarmusch film Only Lovers Left Alive.

Repertoire

Main article: List of composers for lute

Lutes were in widespread use in Europe at least since the 13th century, and documents mention numerous early performers and composers. However, the earliest surviving lute music dates from the late 15th century. Lute music flourished during the 16th and 17th centuries: numerous composers published collections of their music, and modern scholars have uncovered a vast number of manuscripts from the era—however, much of the music is still lost. In the second half of the 17th century lutes, vihuelas and similar instruments started losing popularity, and little music was written for the instrument after 1750. The interest in lute music was revived only in the second half of the 20th century.

Improvisation (making up music on the spot) was, apparently, an important aspect of lute performance, so much of the repertoire was probably never written down. Furthermore, it was only around 1500 that lute players began to transition from plectrum to plucking. That change facilitated complex polyphony, which required that they develop notation. In the next hundred years, three schools of tablature notation gradually developed: Italian (also used in Spain), German, and French. Only the last survived into the late 17th century. The earliest known tablatures are for a six-stringed instrument, though evidence of earlier four- and five-stringed lutes exists. Tablature notation depends on the actual instrument the music is written for. To read it, a musician must know the instrument's tuning, number of strings, etc.

Renaissance and Baroque forms of lute music are similar to keyboard music of the periods. Intabulations of vocal works were very common, as well as various dances, some of which disappeared during the 17th century, such as the piva and the saltarello. The advent of polyphony brought about fantasias: complex, intricate pieces with much use of imitative counterpoint. The improvisatory element, present to some degree in most lute pieces, is particularly evident in the early ricercares (not imitative as their later namesakes, but completely free), as well as in numerous preludial forms: preludes, tastar de corde ("testing the strings"), etc. During the 17th century keyboard and lute music went hand in hand, and by 1700 lutenists were writing suites of dances quite akin to those of keyboard composers. The lute was also used throughout its history as an ensemble instrument—most frequently in songs for voice and lute, which were particularly popular in Italy (see frottola) and England.

The earliest surviving lute music is Italian, from a late 15th-century manuscript. The early 16th century saw Petrucci's publications of lute music by Francesco Spinacino (fl. 1507) and Joan Ambrosio Dalza (fl. 1508); together with the so-called Capirola Lutebook, these represent the earliest stage of written lute music in Italy. The leader of the next generation of Italian lutenists, Francesco Canova da Milano (1497–1543), is now acknowledged as one of the most famous lute composers in history. The bigger part of his output consists of pieces called fantasias or ricercares, in which he makes extensive use of imitation and sequence, expanding the scope of lute polyphony. In the early 17th century Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger (c. 1580–1651) and Alessandro Piccinini (1566–1638) revolutionized the instrument's technique and Kapsberger, possibly, influenced the keyboard music of Girolamo Frescobaldi.

French written lute music began, as far as we know, with Pierre Attaingnant's (c. 1494 – c. 1551) prints, which comprised preludes, dances and intabulations. Particularly important was the Italian composer Albert de Rippe (1500–1551), who worked in France and composed polyphonic fantasias of considerable complexity. His work was published posthumously by his pupil, Guillaume de Morlaye (born c. 1510), who, however, did not pick up the complex polyphony of de Rippe. French lute music declined during the second part of the 16th century; however, various changes to the instrument (the increase of diapason strings, new tunings, etc.) prompted an important change in style that led, during the early Baroque, to the celebrated style brisé: broken, arpeggiated textures that influenced Johann Jakob Froberger's suites. The French Baroque school is exemplified by composers such as Ennemond Gaultier (1575–1651), Denis Gaultier (1597/1603–1672), François Dufaut (before 1604 – before 1672) and many others. The last stage of French lute music is exemplified by Robert de Visée (c. 1655–1732/3), whose suites exploit the instrument's possibilities to the fullest.

The history of German written lute music started with Arnolt Schlick (c. 1460–after 1521), who, in 1513, published a collection of pieces that included 14 voice and lute songs, and three solo lute pieces, alongside organ works. He was not the first important German lutenist, because contemporaries credited Conrad Paumann (c. 1410–1473) with the invention of German lute tablature, though this claim remains unproven, and no lute works by Paumann survive. After Schlick, a string of composers developed German lute music: Hans Judenkünig (c. 1445/50 – 1526), the Neusidler family (particularly Hans Neusidler (c. 1508/09 – 1563)) and others. During the second half of the 16th century, German tablature and German repertoire were gradually replaced by Italian and French tablature and international repertoire, respectively, and the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) effectively stopped publications for half a century. German lute music was revived much later by composers such as Esaias Reusner (fl. 1670), however, a distinctly German style came only after 1700 in the works of Silvius Leopold Weiss (1686–1750), one of the greatest lute composers, some of whose works were transcribed for keyboard by none other than Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), who composed a few pieces for the lute himself (though it is unclear whether they were really intended for the lute, rather than another plucked string instrument or the lautenwerk).

Of other European countries, particularly important are England and Spain. English-written lute music began only around 1540; however, the country produced numerous lutenists, of which John Dowland (1563–1626) is perhaps the most famous. His influence spread very far: variations on his themes were written by keyboard composers in Germany decades after his death. Dowland's predecessors and colleagues, such as Anthony Holborne (c. 1545–1602) and Daniel Bacheler (1572–1619), were less known. Spanish composers wrote mostly for the vihuela; their main genres were polyphonic fantasias and differencias (variations). Luys Milan (c. 1500 – after 1560) and Luys de Narváez (fl. 1526–1549) were particularly important for their contributions to the development of lute polyphony in Spain.

Finally, perhaps the most influential European lute composer was the Hungarian Bálint Bakfark (c. 1526/30–1576), whose contrapuntal fantasias were much more difficult and tighter than those of his Western European contemporaries.

Ottorino Respighi's famous orchestral suites called Ancient Airs and Dances are drawn from various books and articles on 16th- and 17th-century lute music transcribed by the musicologist Oscar Chilesotti, including eight pieces from a German manuscript Da un Codice Lauten-Buch, now in a private library in northern Italy.

20th century revival and composers

The revival of lute-playing in the 20th century has its roots in the pioneering work of Arnold Dolmetsch (1858–1940); whose research into early music and instruments started the movement for authenticity. The revival of the lute gave composers an opportunity to create new works for it.

One of the first such composers was Johann Nepomuk David in Germany. Composer Vladimir Vavilov was a pioneer of the lute revival in the USSR, he was also the author of numerous musical hoaxes. Sandor Kallos and Toyohiko Satoh applied modernist idiom to the lute, Elena Kats-Chernin, Jozef van Wissem and Alexandre Danilevsky minimalist and post-minimalist idiom, Roman Turovsky-Savchuk, Paulo Galvão, Robert MacKillop historicist idiom, and Ronn McFarlane New Age. This active movement by early music specialists has inspired composers in different fields; for example, in 1980, Akira Ifukube, a classical and film composer best known for the Godzilla's theme, wrote the Fantasia for Baroque Lute with the historical tablature notation, rather than the modern staff one.

Tuning conventions

Lute tunings 6-course Early Renaissance lute tuning chart

6-course Early Renaissance lute tuning chart 10-course Late Renaissance/Early Baroque lute tuning chart

10-course Late Renaissance/Early Baroque lute tuning chart 14-course Archlute tuning chart

14-course Archlute tuning chart 15-course Theorbo tuning chart

15-course Theorbo tuning chart

Lutes were made in a large variety of sizes, with varying numbers of strings/courses, and with no permanent standard for tuning. However, the following seems to have been generally true of the Renaissance lute.

A 6-course Renaissance tenor lute would be tuned to the same intervals as a tenor viol, with intervals of a perfect fourth between all the courses except the third and fourth, which differed only by a major third. The tenor lute was usually tuned nominally "in G" (there was no pitch standard before the 20th century), named after the pitch of the highest course, yielding the pattern (G'G) (Cc) (FF) (AA) (dd) (g) from the lowest course to the highest. (Much renaissance lute music can be played on a guitar by tuning the guitar's third string down by a half tone.)

Lute fretboard and tuning explained in 1732 Lute fingerchart, Museum Musicum Theoretico Practicum, 1732.

Lute fingerchart, Museum Musicum Theoretico Practicum, 1732. Lute, chart of position of strings on musical scale.Courses were numbered 1-11, and each open string shown with its corresponding note. In addition to the main strings (A'A') (DD) (FF) (AA) (d) (f), five courses below these were tuned to (C') (D') (E'E) (F'F) (G'G).

Lute, chart of position of strings on musical scale.Courses were numbered 1-11, and each open string shown with its corresponding note. In addition to the main strings (A'A') (DD) (FF) (AA) (d) (f), five courses below these were tuned to (C') (D') (E'E) (F'F) (G'G).

For lutes with more than six courses, the extra courses would be added on the low end. Because of the large number of strings, lutes have very wide necks, and it is difficult to stop strings beyond the sixth course, so additional courses were usually tuned to pitches useful as bass notes rather than continuing the regular pattern of fourths, and these lower courses are most often played without stopping. Thus an 8-course tenor Renaissance lute would be tuned to (D'D) (F'F) (G'G) (Cc) (FF) (AA) (dd) (g), and a 10-course to (C'C) (D'D) (E♭'E♭) (F'F) (G'G) (Cc) (FF) (AA) (dd) (g).

However, none of these patterns were de rigueur, and a modern lutenist occasionally retunes one or more courses between pieces. Manuscripts bear instructions for the player, e.g., 7 chœur en fa = "seventh course in fa" (= F in the standard C scale).

The early 17th century was a period of considerable development for the lute, particularly with new tuning schemes developed in France. At this time French lutenists began to explore the expressive capabilities of the lute through experimentation in tuning schemes on the instrument. Today these tunings are often labeled as transitional tunings or Accords nouveaux (French: “new tunings”). Transitional tunings document the transition from the established Renaissance lute tuning, to the later established Baroque d-minor tuning scheme.

This development in tuning is credited to French lutenists of the early 17th century, who began increasing the number of major or minor thirds on the adjacent open strings of the 10-course lute. As a result the French lutenist found a more sonorous sound and increased sympathetic vibration on the instrument. This led to new compositional styles and playing techniques on the instrument, most notably the Style brisé (French: "broken style"). Manuscript sources from the first half of the 17th century provide evidence that French transitional tunings gained popularity and were adopted across much of continental Europe.

The most used transitional tunings during this time were known as the "sharp" and "flat" tunings. Read from the tenth to the first course on a 10-course lute, the sharp tuning reads: C, D, E, F, G, C, F, A, C, E. The flat tuning reads, C, Db, Eb, F, G, C, F, Ab, C, Eb.

However, by around 1670 the scheme known today as the "Baroque" or "D minor" tuning became the norm, at least in France and in northern and central Europe. In this case, the first six courses outline a d-minor triad, and an additional five to seven courses are tuned generally scalewise below them. Thus the 13-course lute played by composer Sylvius Leopold Weiss would have been tuned (A″A') (B″B') (C'C) (D'D) (E'E) (F'F) (G'G) (A'A') (DD) (FF) (AA) (d) (f), or with sharps or flats on the lower 7 courses appropriate to the key of the piece.

Modern lutenists tune to a variety of pitch standards, ranging from A = 392 to 470 Hz, depending on the type of instrument they are playing, the repertory, the pitch of other instruments in an ensemble and other performing expediencies. No attempt at a universal pitch standard existed during the period of the lute's historical popularity. The standards varied over time and from place to place.

See also

Instruments

European Lutes:

- Angélique

- Archlute

- Bouzouki

- Cobza

- Gittern

- Kobza

- Laouto

- Mandola

- Mandolin

- Mandore

- Mandora or Gallichon

- Oúti

- Swedish lute

- Torban

- Theorbo

- Vihuela

African Lutes:

Asian Lutes:

- Barbat

- Bipa

- Biwa

- Dombra

- Dutar

- Dramyin

- Komuz

- Kutiyapi

- Oud

- Panduri

- Pipa

- Qanbūs

- Qinqin

- Rubab

- Sanshin

- Sanxian

- Sapeh

- Setar

- Shamisen

- Sitar

- Sueng

- Swarabat

- Tanbur

- Tar

- Veena

- Yueqin

South American Lutes:

Players

See also: Category:Lutenists- Robert Barto

- Timothy Burris

- François de Chancy

- Xavier Díaz-Latorre

- Thomas Dunford

- Eduardo Eguez

- Johann Georg Hamann

- Lutz Kirchhof

- Rolf Lislevand

- Nigel North

- Paul O'Dette

- Hopkinson Smith

- Christopher Wilke

- Jozef van Wissem

- Evangelina Mascardi

Makers

- Cezar Mateus

- Stephen Murphy

- David Rubio

- Andrew Rutherford

- Antonio Stradivari

- Tieffenbrucker

- Joachim Tielke

Notes

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. lute

- Curt Sachs (1940). The History of Musical Instruments - Curt Sachs.

- Grout, Donald Jay (1962). "Chapter 7: New Currents In The Sixteenth Century". A History Of Western Music. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London. p. 202. ISBN 0393937119.

By far the most popular household solo instrument of the Renaissance was the lute

- Sachs, Curt (1914). "The history of Musical Instruments" (PDF). The Public's Library and Digital Archive.

- ^ Sachs, Curt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 464. ISBN 9780393020687.

- ^ Sachs, Curt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 255–257. ISBN 9780393020687.

- "ATLAS of Plucked Instruments". www.atlasofpluckedinstruments.com. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- Sachs, Curt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 102–103. ISBN 9780393020687.

- Sachs, Curt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9780393020687.

- ^ Dumbrill 1998, p. 321

- Dumbrill 2005, pp. 305–310. "The long-necked lute would have stemmed from the bow-harp and eventually became the tunbur; and the fat-bodied smaller lute would have evolved into the modern Oud ... the lute pre-dated the lyre which can therefore be considered as a development of the lute, rather than the contrary, as had been thought until quite recently ... Thus the lute not only dates but also locates the transition from musical protoliteracy to musical literacy ..."

- "Cylinder Seal". British Museum. Culture/period Uruk, Date c. 3100 BC, Museum number 41632.

- Dumbrill 1998, p. 310

- Dumbrill 2005, pp. 319–320. "The long-necked lute in the OED is orthographed as tambura; tambora, tamera, tumboora; tambur(a) and tanpoora. We have an Arabic Õunbur; Persian tanbur; Armenian pandir; Georgian panturi. and a Serbo-Croat tamburitza. The Greeks called it pandura; panduros; phanduros; panduris or pandurion. The Latin is pandura. It is attested as a Nubian instrument in the third century BC. The earliest literary allusion to lutes in Greece comes from Anaxilas in his play The Lyre-maker as 'trichordos' ... According to Pollux, the trichordon (sic) was Assyrian and they gave it the name pandoura...These instruments survive today in the form of the various Arabian tunbar ..."

- ^ During, Jean (1988-12-15). "Barbat". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- "Bracket with two musicians 100s, Pakistan, Gandhara, probably Butkara in Swat, Kushan Period (1st century – 20)". The Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Sachs, Curt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 159–161. ISBN 9780393020687.

- Menocal, María Rosa; Scheindlin, Raymond P.; Sells, Michael Anthony, eds. (2000), The Literature of Al-Andalus, Cambridge University Press

- Gill, John (2008). Andalucia: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-01-95-37610-4.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780521779333.

- Davila, Carl (2009). "Fixing a Misbegotten Biography: Ziryab in the Mediterranean World". Al-Masaq: Islam in the Medieval Mediterranean. 21 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1080/09503110902875475. S2CID 161670287.

- "The journeys of Ottoman ouds". oudmigrations. 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- ^ Lawson, Colin; Stowell, Robin, eds. (2012-02-16). The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-18442-4.

- Boase, Roger (1977). The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship. Manchester University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7190-0656-2.

- Edwards, Vane. "An Illustrated History of the Lute Part One". vanedwards.co.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

Bletschacher (1978) has argued that this was due largely to the royal visits of Friedrich II with his magnificent Moorish Sicilian retinue to the towns in this valley between 1218 and 1237.

- Edwards, Vane. "An Illustrated History of the Lute Part Two". vanedwards.co.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

By 1500 the first written records confirm the existence of several families making lutes as a trade in and around Füssen in the Lech valley. Most of the famous names of 16th and 17th century lutemaking seem to have come originally from around this small area of Southern Germany. By 1562 the Füssen makers were sufficiently well established to set up as a guild with elaborate regulations which have survived (see Bletschacher, 1978, and Layer, 1978).

- "Jakob Lindberg Homepage". musicamano.com. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- Smith 2002, p. 9.

- Pourjavady, Amir Hossein (Autumn 2000 – Winter 2001). "Journal Article Review Reviewed Works: The Science of Music in Islam. Vols. 1-2, Studies in Oriental Music by Henry George Farmer, Eckhard Neubauer; The Science of Music in Islam. Vol. 3, Arabisch Musiktheorie von den Anfängen bis zum 6./12. Jahrhundert by Eckhard Neubauer, Fuat Sezgin; The Science of Music in Islam. Vol. 4, Der Essai sur la musique orientale von Charles Fonton mit Zeichnungen von Adanson by Eckhard Neubauer, Fuat Sezgin". Asian Music. 32 (1): 206–209. doi:10.2307/834339. JSTOR 834339.

- Dumbrill 1998, p. 319. "'rud' comes from the Sanskrit 'rudrī' which means 'stringed instrument' The word spreads on the one hand via the Indo-European medium into the Spanish 'rota'; French 'rotte'; Welsh 'crwth', etc, and on the other, via the Semitic medium, into Arabic 'ud; Ugaritic 'd; Spanish 'laúd'; German 'Laute'; French 'luth'"

- "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org.

- "Strong's Hebrew: 181. אוּד (ud) -- a brand, firebrand". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- Farmer, Henry George (1939). "The Structure of the Arabian and Persian Lute in the Middle Ages". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: 41–51 .

- "Photo of lute internal". www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~wbc.

- Mattheson, Johann (1713). Das neu Eroffnet Orchestre. Hamburg. pp. 247ff.

- Apel 1949, p. 54.

- Campbell, Margaret (1995). Henry Purcell (Glory Of His Age). Open University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-19-282368-X. (about Alfred Dolmetsch) "His discoveries were so fruitful that he decided to concentrate on performing early music on original instruments, something that had not been attempted hitherto—at least not outside a private drawing-room."

- Yokomizo, Ryoichi (1996). 伊福部昭ギター・リュート作品集 (Akira Ifukube - Works for Guitar and Lute) (CD Booklet). Yoh Nishimura and Deborah Minkin. Japan: FONTEC. p. 4.

- Spring, M. (2001). From Renaissance to Baroque: a continental excursus, 1600-1650. In The lute in Britain: a history of the instrument and its music (pp. 290–306). essay, Oxford University Press.

- "Forms of the Lute". The Lute Society of America. Trustees of Dartmouth College. 24 May 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

Bibliography

- Articles in Journal of the Lute Society of America (1968–), The Lute (1958–), and other journals published by the various national lute societies.

- Apel, Willi (1949). The notation of polyphonic music 900–1600. Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America. OCLC 248068157.

- Dumbrill, Richard J. (1998). The Archaeomusicology of the Ancient Near East. London: Tadema Press.

- Dumbrill, Richard J. (2005). The Archaeomusicology of the Ancient Near East. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-5538-3. OCLC 62430171.

- Lundberg, Robert (2002). Historical Lute Construction. Guild of American Luthiers.

- Neubauer, Eckhard (1993). "Der Bau der Laute und ihre Besaitung nach arabischen, persischen und türkischen Quellen des 9. bis 15. Jahrhunderts". Zeitschrift für Geschichte der arabisch-islamischen Wissenschaften. Vol. 8. pp. 279–378.

- Pio, Stefano (2012). Viol and Lute Makers of Venice 1490 - 1640. Venice Research. ISBN 978-88-907252-0-3.

- Pio, Stefano (2004). Violin and Lute Makers of Venice 1630 - 1760. Venice Research. ISBN 978-88-907252-2-7.

- Rebuffa, Davide (2012). Il Liutoy. Palermo: L'Epos. ISBN 978-88-830237-7-4.

- Schlegel, Andreas (2006). The Lute in Europe. The Lute Corner ISBN 978-3-9523232-0-5

- Smith, Douglas Alton (2002). A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Lute Society of America ISBN 0-9714071-0-X ISBN 978-0-9714071-0-7

- Spring, Matthew (2001). The Lute in Britain: A History of the Instrument and its Music. Oxford University Press.

- Vaccaro, Jean-Michel (1981). La musique de luth en France au XVIe siècle.

External links

Societies

- The Lute Society of America (America)

- The Belgian Lute Society (Belgium)

- The French Lute Society (France)

- The German Lute Society (Germany)

- The Lute Society of Japan (Japan)

- The Lute and Early Guitar Society (Japan, Founded by Toyohiko Satoh)

- The Dutch Lute Society (the Netherlands)

- The Lute Society (UK)

Online music and other useful resources

- reneszanszlant.lap.hu collection of many useful links: luthiers/lute makers, lute players, tablatures, etc. (in English and Hungarian)

- ABC Classic FM presents: Lute Project videos Watch Tommie Andersson play the theorbo, 7-course & 10-course lutes.

- Wayne Cripps' lute pages

- Joachim Tielke The website for the great Hamburg lute maker Joachim Tielke

- Musick's Handmade Facsimiles/Scans (Dowland, etc.) and pdfs - by Alain Veylit

- Sarge Gerbode's Lute Page 7000+ lute solo and ensemble pieces by 300+ composers in midi, PDF, TAB, and Fronimo formats

- Another Lute Website Categorized view on youtube videos of over 250 lute composers

- Contemporary and Modern Lute Music Modern (post 1815) and Contemporary Lute Music. A list of modern lute music written after 1815

- Music Collection in Cambridge Digital Library. One of the most important collections of manuscript music in Cambridge University Library is the group of nine lute manuscripts copied by Mathew Holmes in the early years of the seventeenth century.

- Le Luth Doré Urtext music editions The most important collection of modern Urtext music editions for lute.

Photos of historic instruments

- Photos of historic lutes at the Cité de la Musique in Paris

- Instruments et oeuvres d'art – search-phrase: Mot-clé(s) : luth

- Facteurs d'instruments – search-phrase: Instrument fabriqué : luth

- Photothèque – search-phrase: Instrument de musique, ville ou pays : luth

Articles and resources

- Pioneers of the Lute Revival by Jo Van Herck (Belgian Lute Academy)

- Original: Over de pioniers van de luitrevival; Luthinerie / Geluit no. 15 (September 2001) and no. 16 (December 2001)

- Photos and Paintings

- French Lutenists and French Lute Music in Sweden

- La Rhétorique des Dieux

- Lautenweltadressbuch: A List of Extant Historical Lutes from Lute Society of America

| Lute | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types by region |

| ||||||

| Related instruments | |||||||

| Other topics | |||||||

| Renaissance music | |

|---|---|

| List of Renaissance composers | |

| Early (1400–1470) | |

| Middle (1470–1530) | |

| Late (1530) |

|

| Mannerism and Transition to Baroque c.1600 |

|

| Composition schools | |

| Musical forms | |

| Traditions | |

| Music publishing | |

| Background | |

| ← Medieval musicBaroque music → | |