| Malla Republic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 7th century BCE–c. 4th century BCE | |||||||

Malla among the Gaṇasaṅghas Malla among the Gaṇasaṅghas | |||||||

Malla, Vajji (the dependencies of Licchavi within the Vajjika League), and other Mahajanapadas in the Post Vedic period Malla, Vajji (the dependencies of Licchavi within the Vajjika League), and other Mahajanapadas in the Post Vedic period | |||||||

| Status | Republic of the Vajjika League | ||||||

| Capital | Kusinārā Pāvā | ||||||

| Common languages | Prakrit | ||||||

| Religion | Historical Vedic religion Buddhism Jainism | ||||||

| Government | Aristocratic Republic | ||||||

| Gaṇa Mukhya | |||||||

| Legislature | Sabhā | ||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||

| • Established | c. 7th century BCE | ||||||

| • Disestablished | c. 4th century BCE | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||

Malla (Prakrit: 𑀫𑀮𑁆𑀮𑀈 Mallaī; Pali: Malla; Sanskrit: मल्ल Malla) was an ancient Indo-Aryan tribe of north-eastern Indian subcontinent whose existence is attested during the Iron Age. The population of Malla, the Mallakas, were divided into two branches, each organised into a gaṇasaṅgha (an aristocratic oligarchic republic), presently referred to as the Malla Republics, which were part of the larger Vajjika League.

Location

The Mallakas lived in the region now covered by the Gorakhpur district in India, although their precise borders are yet to be determined. The Mallakas' neighbours to the east across the Sadānirā river were the Licchavikas, their neighbours to the west were the Sakyas, Koliyas, Moriyas, and Kauśalyas, the southern neighbours of the Mallakas were the Kālāmas and the Gaṅgā river, and the northern Mallaka borders were the Himālaya mountains. The territory of the Mallakas was a tract of land between the Vaidehas and the Kauśalyas.

The territories of the two Malla republics were divided by the river named Hiraññavatī in Pāli, and Hiraṇyavatī in Sanskrit, and the two Malla republics respectively had their capitals at Kusinārā, identified with the modern village of Kāsiā in Kushinagar, and at Pāvā (now known as Fazilnagar). Kusinārā was close to the Sakya capital of Kapilavatthu to its north-east, and Pāvā was close to the Licchavika capital of Vesālī.

Name

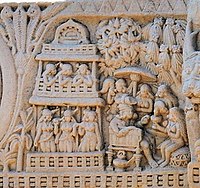

Conjectural reconstruction of the main gate of Kusinārā, capital of one of the Malla republics, circa 500 BCE adapted from a relief at Sanchi.

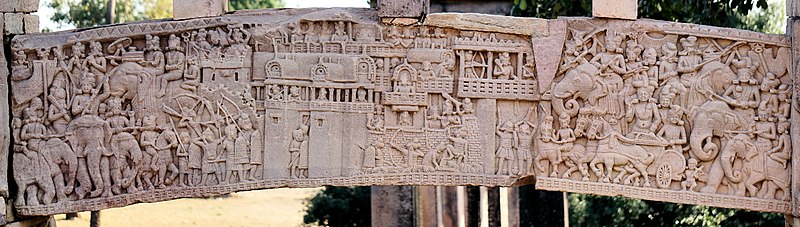

Conjectural reconstruction of the main gate of Kusinārā, capital of one of the Malla republics, circa 500 BCE adapted from a relief at Sanchi. City of Kusinārā in the 5th century BCE according to a 1st-century BCE frieze in Sanchi Stupa 1 Southern Gate.

City of Kusinārā in the 5th century BCE according to a 1st-century BCE frieze in Sanchi Stupa 1 Southern Gate.

The Mallakas are called Malla in Pāli texts, Mallaī in Jain Prākrit texts, and Malla in Sanskrit texts.

History

Statehood

The Mallakas were an Indo-Aryan tribe in the eastern Gangetic plain in the Greater Magadha cultural region. Similarly to the other populations of the Greater Magadha cultural area, Mallakas were initially not fully Brahmanised despite being an Indo-Aryan people, but, like the Vaidehas, they later became Brahmanised and adopted the Vāseṭṭha (in Pali) or Vaśiṣṭha (in Sanskrit) gotra. At some point in time, the Mallakas became divided into two separate republics with their respective capitals at Kusinārā and Pāvā, possibly due to internal trouble, and henceforth the relations between the two Mallaka republics remained uncordial. Both Mallaka republics nevertheless became members of the Licchavi-led Vajjika League, within which, unlike the Vaidehas, they maintained their own sovereign rights because they had not been conquered by the Licchavikas, and the Mallakas held friendly relations with the Licchavikas, the Vaidehas, and the Nāyikas who were the other members of this league.

However occasional tensions between the Mallakas and the Licchavikas did arise, such as in the case of the man named Bandhula, a Mallaka who, thanks to his education received in Takṣaśilā, had offered his services as a general to the Kauśalya king Pasenadi so as to maintain the good relations between the Mallakas and Kosala. Bandhula, along with his wife Mallikā, violated the Abhiseka-Pokkharaṇī sacred tank of the Licchavikas, which resulted in armed hostilities between the Kauśalyas and the Licchavikas. Bandhula was later treacherously murdered along with his sons by Pasenadi, and, in retaliation, some Mallakas helped Pasenadi's son Viḍūḍabha usurp the throne of Kosala to avenge the death of Bandhula, after which Pasenadi fled from Kosala and died in front of the gates of the Māgadhī capital of Rājagaha.

The Buddha arrived in Pāvā shortly after the Mallakas there had inaugurated their new santhāgāra, which they had named Ubbhataka. From Pāvā, the Buddha and his followers went to Kusinārā, and on the way they crossed two rivers, the first one being named Kakutthā in Pali and Kukustā in Sanskrit, and the second one being the Hiraññavatī which separated the two Mallaka republics. The Buddha spent his final days in the Malla republic of Kusinārā, and when he sent Ānanda to inform the Mallakas of Kusinārā of his impending death, Ānanda found the Mallaka Council holding a meeting about public affairs in their santhāgāra.

Map of the eastern Gangetic plain before Ajātasattu's conquests

Map of the eastern Gangetic plain before Ajātasattu's conquests(Malla shown within the Vajjika League)

Map of the eastern Gangetic plain after Ajātasattu's conquest of the Vajjika League and of Moriya

Map of the eastern Gangetic plain after Ajātasattu's conquest of the Vajjika League and of Moriya

When Ānanda went again to the Mallakas of Kusinārā to inform them of the Buddha's passing, he found them this time holding a meeting to discuss the funeral ceremony of the Buddha in the santhāgāra. After the Buddha's cremation, his remains were honoured in the santhāgāra of Kusinārā for seven days, and it was in this santhāgāra that the Mallakas of Kusinārā received the envoys of Magadha, Licchavi, Shakya, Buli, Koliya, the Mallakas of Pāvā, and Moriya, who all went to Kusinārā to claim their shares of the Buddha's relics. The Licchavikas, the Mallakas, and the Sakyas were able to claim shares of the relics, but the other members of the Vajjika League, the Vaidehas and the Nāyikas, were not among the states claiming a share because they were dependencies of the Licchavikas without their own sovereignty, and therefore could not put forth their own claim while Licchavi could. The Mallakas of Pāvā were the first ones to arrive with an army to Kusinārā, and they put forth their claim to the relics in rude and hostile terms. In the end, each Malla republic obtained a share of the Buddha's relics and built their own stūpas and gave their own feasts to commemorate this event.

After the death of the 24th Jain Tīrthaṅkara, Mahāvīra, the Mallakas and the Licchavikas jointly instituted a festival of lights to commemorate his passing.

Decline

See also: Magadha-Vajji warThe relations of the Licchavikas, who led the Vajjika League which the Mallakas were part of, with their southern neighbour, the kingdom of Magadha, were initially good, and the wife of the Māgadhī king Bimbisāra was the Vesālia princess Vāsavī, who was the daughter of the Licchavika Nāyaka Sakala's son Siṃha. There were nevertheless occasional tensions between Licchavi and Magadha, such as the competition at the Mallaka capital of Kusinārā over acquiring the relics of the Buddha after his death.

In another case, the Licchavikas once invaded Māgadhī territory from across the Gaṅgā, and at some point the relations between Magadha and Licchavi permanently deteriorated as result of a grave offence committed by the Licchavikas towards the Māgadhī king Bimbisāra.

The hostilities between Licchavi and Magadha continued under the rule of Ajātasattu, who was Bimbisāra's son with another Licchavika princess, Vāsavī, after he had killed Bimbisāra and usurped the throne of Magadha. Eventually Licchavi supported a revolt against Ajātasattu by his younger step-brother and the governor of Aṅga, Vehalla, who was the son of Bimbisāra by another Licchavika wife of his, Cellanā, a daughter of Ceḍaga, who was the head of both the Licchavi republic and the Vajjika League; Bimbisāra had chosen Vehalla as his successor following Ajātasattu's falling out of his favour after the latter had been caught conspiring against him, and the Licchavikas had attempted to place Vehalla on the throne of Magadha after Ajātasattu's usurpation and had allowed Vehalla to use their capital Vesālī as base for his revolt. After the failure of this rebellion, Vehalla sought refuge at his grandfather's place in the Licchavika and Vajjika capital of Vesālī, following which Ajātasattu repeatedly attempted to negotiate with the Licchavikas-Vajjikas. After Ajātasattu's repeated negotiation attempts ended in failure, he declared war on the Vajjika League in 484 BCE.

Tensions between Licchavi and Magadha were exacerbated by the handling of the joint Māgadhī-Licchavika border post of Koṭigāma on the Gaṅgā by the Licchavika-led Vajjika League who would regularly collect all valuables from Koṭigāma and leave none to the Māgadhīs. Therefore Ajātasattu decided to destroy the Vajjika League in retaliation, but also because, as an ambitious empire-builder whose mother Vāsavī was Licchavika princess of Vaidehī descent, he was interested in the territory of the former Mahā-Videha kingdom which by then was part of the Vajjika League. Ajātasattu's hostility towards the Vajjika League was also the result of the differing forms of political organisation between Magadha and the Vajjika League, with the former being monarchical and the latter being republican, not unlike the opposition of the ancient Greek kingdom of Sparta to the democratic form of government in Athens, and the hostilities between the ancient Macedonian king Philip II to the Athenian and Theban republics.

As important members of the Vajjika League, the Malla republics were also threatened by Ajātasattu, and the Vajjika Gaṇa Mukhya Ceḍaga held war consultations with the rājās of the Licchavikas and Mallikas before the fight started. The Mallakas therefore fought on the side of the other confederate tribes of the league against Magadha. The military forces of the Vajjika League were initially too strong for Ajātasattu to be successful against them, and it required him having recourse to diplomacy and intrigues over the span of a decade to finally defeat the Vajjika League by 468 BCE and annex its territories, including Licchavi, Videha and Nāya, to the kingdom of Magadha. The Mallakas also became part of Ajātasattu's Māgadhī empire, although they were allowed a limited degree of autonomy in terms of their internal administration, and they stopped existing as a republican tribe when the Maurya dynasty ruled Magadha or shortly after.

Social and political organisation

Republican institutions

The Assembly

Just like a Vaidehas, Licchavikas, and Nāyikas, the Mallakas were a kṣatriya tribe, and each of the republics of the Mallakas were organised into a gaṇasaṅgha (an aristocratic oligarchic republic), which had a ruling Assembly consisting of the heads of the kṣatriya clans belonging to the Vāseṭṭha/Vaśiṣṭha gotra, and who were given the title of rājās. The position of rājā was hereditary, and after the death of one of them, his eldest son would succeed him by being introduced to the Assembly following a ceremony held, for the Mallakas of Kusinārā, at the Makuṭa-bandhana, which was a shrine holding an important political meaning for the republic (the Mallakas of Pāvā had a similar shrine of their own). Similarly to that of the Licchavikas, the Mallaka General Assembly had a large number of members, with the meetings being only rarely attended by all of them.

The Mallaka republics, like the other gaṇasaṅgha of the Vajjika League, held their Assembly and Council meetings in their own santhāgāras.

The Councils

Like the Licchavikas, the Mallakas' Assemblies met rarely while the Assemblies' inner councils, the Mallaka Councils, consisting of four members for the Mallakas of Kusinārā and of five members for the Mallakas of Pāvā, met more often and performed the public administration within each republic. These Councils were the sovereign bodies of the Mallaka republics.

Customs

The Manusmṛiti refers to the Mallakas as Vrāṭyakṣatriyas, that is kṣatriyas who had not been initiated, because they did not practice orthodox Vedic traditions.

See also

References

- ^ Sharma 1968, p. 169-181.

- Levman, Bryan G. (2014). "Cultural Remnants of the Indigenous Peoples in the Buddhist Scriptures". Buddhist Studies Review. 30 (2): 145–180. doi:10.1558/bsrv.v30i2.145. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Bronkhorst, J. (2007). Greater Magadha, Studies in the culture of Early India, p. 6. Leiden, Boston, MA: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004157194.i-416. ISBN 9789047419655.

- ^ Sharma 1968, p. 136-158.

- ^ Sharma 1968, p. 85-135.

- Hackin, J. (1994). Asiatic Mythology. Asian Educational Services. p. 83ff. ISBN 9788120609204.

Sources

- Sankrityayan, Rahul (2010). "Buddhacharya"- Life and Teachings of the Buddha (in Hindi). Gautam Book Centre. ISBN 9789380292175.

- Sharma, J. P. (1968). Republics in Ancient India, C. 1500 B.C.-500 B.C. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-02015-3.

Further reading

- Gorakhpur Janpad aur Uski Kshatriya Jatiyon Ka Itihaas By Dr. Rajbali Pandey, pp. 291–292

- Kshatriya Rajvansh by Dr. Raghunath Chand Kaushik

- Bhagwan Buddh ke Samkalin Anuyayi tatha Buddha Kendra By Tripatkacharya, Mahopadhyaya Bikshu Buddhamitra, pp. 274–283.

| Mahajanapadas | |

|---|---|

| Great Indian Kingdoms (c. 600 BCE–c. 300 BCE) | |