| Maria Luisa of Spain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by François-Xavier Fabre Portrait by François-Xavier Fabre | |||||

| Queen consort of Etruria | |||||

| Tenure | 21 March 1801 – 27 May 1803 | ||||

| Duchess of Lucca | |||||

| Reign | 9 June 1815 – 13 March 1824 | ||||

| Predecessor | Elisa Bonaparte (as Princess of Lucca) | ||||

| Successor | Charles I | ||||

| Born | (1782-07-06)6 July 1782 Palace of San Ildefonso, Segovia, Spain | ||||

| Died | 13 March 1824(1824-03-13) (aged 41) Rome, Papal States | ||||

| Burial | El Escorial, Madrid | ||||

| Spouse | Louis I of Etruria | ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Charles IV of Spain | ||||

| Mother | Maria Luisa of Parma | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Maria Luisa of Spain (Spanish pronunciation: [maˈɾi.a ˈlwisa], 6 July 1782 – 13 March 1824) was a Spanish infanta, daughter of King Charles IV and his wife, Maria Luisa of Parma. In 1795, she married her first cousin Louis, Hereditary Prince of Parma. She spent the first years of her married life at the Spanish court where their first child, Charles, was born.

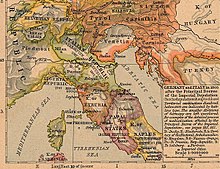

In 1801 the Treaty of Aranjuez made her husband King of Etruria, a kingdom created from the former Grand Duchy of Tuscany in exchange for the renunciation of the Duchy of Parma. They arrived in Florence, the capital of the new kingdom, in August 1801. During a brief visit to Spain in 1802, Maria Luisa gave birth to her second child. Her husband's reign in Etruria was marred by his ill health. He died in 1803, at the age of 30, following an epileptic crisis. Maria Luisa acted as regent for their son. During her government in Florence, she tried to gain the support of her subjects, but her administration of Etruria was cut short by Napoleon Bonaparte, who forced her to leave with her children in December 1807. As part of the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Napoleon incorporated Etruria to his domains.

After a futile interview with Napoleon in Milan, Maria Luisa looked for refuge in exile with her family in Spain. The Spanish court was deeply divided and a month after her arrival the country was thrown into unrest when a popular uprising, known as the Mutiny of Aranjuez, forced Maria Luisa's father to abdicate in favor of her brother Ferdinand VII. Napoleon invited father and son to Bayonne, France, with the excuse of acting as a mediator, but gave the kingdom to his brother Joseph. Napoleon called the remaining members of the Spanish royal family to France and at their departure on 2 May 1808, the citizens of Madrid rose up against the French occupation. In France, Maria Luisa was reunited in exile with her parents. She was the only member of the Spanish royal family to oppose Napoleon directly. After her secret plan to escape was discovered, Maria Luisa was separated from her son and placed with her daughter as prisoners in a Roman convent.

Maria Luisa, mostly known as the Queen of Etruria during her lifetime, regained her freedom in 1814 at the fall of Napoleon. In the following years, she continued to live in Rome, hoping to recover her son's former domains. To put forward her case she wrote a book of memoirs, but was disappointed when the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) compensated her not with Parma, but with the smaller Duchy of Lucca, which had been carved out of Tuscany. As a consolation, she was allowed to retain the honours of a queen. Initially reluctant to accept this accord, Maria Luisa did not take the government of Lucca until December 1817. As a reigning duchess of Lucca, she disregarded the constitution imposed by the Congress of Vienna. While spending time in her palace in Rome, she died of cancer at the age of 41.

Infanta of Spain

Born at the Palace of San Ildefonso, Segovia, Spain, Maria Luisa was the third surviving daughter of King Charles IV of Spain and his wife Maria Luisa of Parma, a granddaughter of Louis XV and the popular Queen Marie Leczinska. She was given the names Maria Luisa Josefina Antonieta, after an older sister, Maria Luisa Carlota, who had died just four days before Maria Luisa's birth, on 2 July, and her mother.

In 1795, Maria Luisa's first cousin, Louis, Hereditary Prince of Parma, came to the Spanish court to finish his education. There was an understanding between the two royal families that Louis would marry one of the daughters of Charles IV. It was anticipated that he would marry the Infanta Maria Amalia, Charles IV's eldest unmarried daughter. She was fifteen years old at the time and of a timid and melancholic nature. Louis, who was equally shy and reserved, preferred her younger sister, Maria Luisa, who although only twelve, was of a more cheerful disposition and somewhat better looking. All four daughters of Charles IV were short and plain, but Maria Luisa was clever, lively and amusing. She had dark curly hair, brown eyes and a Grecian nose. Although not beautiful, her face was expressive and her character lively. She was generous, kindhearted and devout. Both infantas were favorably impressed by the Prince of Parma, a tall and handsome young man, and when he ultimately chose the younger sister, Queen Maria Luisa readily agreed to the change of bride.

Marriage

Louis was created Infante of Spain and married Maria Luisa on 25 August 1795 at the Royal Palace of La Granja. In a double wedding with her sister, Maria Amalia, who was the original intended bride, married her much older uncle, Infante Antonio. The marriage between the two different personalities turned out to be happy, though it was clouded by Louis' ill health: He was frail, suffering chest problems, and since a childhood accident when he hit his head on a marble table, had epileptic seizures. As the years went on his health deteriorated and he grew to be increasingly dependent on his wife. The young couple remained in Spain during the early years of their marriage, which were to be the happiest period of their lives. In early 1796, the couple traveled through Castilla, Extramadura all the way to Portugal.

Maria Luisa was only thirteen when she married, and her first child was not born for another four years. Her first son, Charles Louis, was born in Madrid on 22 December 1799. Afterwards, the couple wanted to go to Parma, the lands they were going to inherit, but the King and Queen were reluctant to allow their departure. They were still in Spain in the spring of 1800 and staying at the Palace in Aranjuez when they were painted with the royal family in The Family of Charles IV by Goya.

Queen of Etruria

Maria Luisa's life was deeply marked by Napoleon Bonaparte's actions. Napoleon was interested in having Spain as an ally against the United Kingdom. In the summer of 1800, he sent his brother Lucien to the Spanish court with the proposal that would result in the Treaty of Aranjuez. Napoleon, who had conquered Italy, proposed to compensate the House of Bourbon for their loss of the Duchy of Parma by creating the new Kingdom of Etruria for Louis, heir of Parma. The new kingdom was created out of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

To make way for the Bourbons, Grand Duke Ferdinand III was ousted and compensated with Salzburg. Maria Luisa, who had never lived away from her own family and was totally inexperienced in political affairs, opposed the plan. One of Napoleon's conditions was that the young couple had to go to Paris and there receive from him the investiture of their new sovereignty, before taking possession of Etruria. Maria Luisa was reluctant to make a trip to France, where only seven years earlier her relatives Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had been executed. However, pressed also by her family, she did as she was told. On 21 April 1801 the couple and their son left Madrid, crossed the border in Bayonne and traveled incognito to France under the name of Counts of Livorno. Napoleon received them with great attentions, at their arrival in Paris on 24 May. At first, the young couple did not make a good impression. In her memoirs, the Duchess of Abrantes described Maria Luisa's character as a "mixture of shyness and haughtiness which at first gave restraint to her conversation and manners".

On her part, the Infanta did not enjoy her visit to Paris. Ill most of the time, she had a fever, often had to stay in bed and only reluctantly took part in the diversions on her honor. She was anxious about the health of her husband, who depended on her for everything. One day, as Louis got out of the carriage at Château de Malmaison, where they were going to dine, he suddenly fell to the ground during an epileptic seizure. The Duchess of Abrantès described the scene in her memoirs:

"The Queen appeared much distressed and tried to conceal her husband; ... he was as pale as a death and his features completely altered ..."

In the recollections of Napoleon's valet, Maria Luisa left a more favorable impression than her husband: "The Queen of Etruria was, in the opinion of the First Consul, more sagacious and prudent than her husband.. dressed herself in the morning for the whole day, and walked in the gardens, her head adorned with flowers or a diadem, and wearing a dress, the train of which swept up the sand of the walk: often also carrying in her arms one of her children.., by night the toilet of her Majesty was somewhat disarranged. She was far from pretty, and her manner were not suited to her rank. But, which fully atoned for all of this, she was good-tempered, much loved by those in her service, and scrupulous in fulfilling the duties of wife and mother. In consequence, the First Consul, who made a great point of domestic virtue, professed for her the highest esteem."

On 30 June, after staying in Paris for three weeks, Maria Luisa and her husband, headed south toward Parma. In Piacenza they were greeted by Louis' parents, together they went to Parma and Maria Luisa met her husband's two unmarried sisters. They found Louis already speaking Italian with a foreign accent while Maria Luisa's Italian was often mixed with Spanish words. After three weeks in Parma they entered Etruria. On 12 August they arrived at Florence. The French general Murat had been sent to Florence to prepare the Pitti Palace for them. But the King and Queen of Etruria did not have an auspicious start in their new life. Maria Luisa suffered a miscarriage, while her frail husband's health deteriorated further, fits of epilepsy becoming more frequent. The Pitti Palace, the residence of the King and Queen, was the former house of the Medici dukes. The palace had been practically abandoned after the death of the last Medici and the ousted Grand Duke Ferdinand had taken most of its valuables with him. Short of money, Maria Luisa and her husband were forced to furnish the Pitti Palace borrowing furniture from the local nobility.

Maria Luisa and Louis were both full of good intentions but they were received with hostility by the population and the nobility that missed the popular Grand Duke and saw them as just mere tools in the hands of the French. Etruria's finances were in deplorable state; the country was ruined by war, bad harvest and the cost to have to maintain the unpopular French troops stationed in Etruria, that only much later were replaced by Spanish troops sent by Charles IV. In 1802, Maria Luisa and her husband were invited to Spain to attend the double wedding of her brother Ferdinand with Maria Antonia of Naples, and of her youngest sister, Maria Isabel, with Francis I of Naples. With Etruria's financial and economic difficulties, Louis' health failing and Maria Luisa in an early state of pregnancy, going abroad was clearly not expedient, but under the pressure of her father and wanted to see her family, they started the journey to her native country.

Louis felt very ill before boarding the ship, waiting for his full recovery delayed their plans for a month. Once at sea, they had a storm for three days. On the second day aboard, 2 October 1802, still in open waters before arriving at Barcelona, Maria Luisa under difficulties gave birth to her daughter Maria Luisa Carlota (named after Maria Luisa's older deceased sister). At first, doctors thought that both mother and daughter would not survive. The couple also found out that they arrived too late for the wedding. Maria Luisa, still very ill, waited three days on the ship to recover before she went ashore in Barcelona, where her parents were waiting for her. One week after they arrival they got news that Louis's father, Ferdinand, had died. Ill and unhappy, Louis wanted to return as soon as possible to his Italian states, but Charles IV and Maria Luisa insisted to take them to the court in Madrid. It was not until 29 December when they were allowed to start the trip leaving Spain by sea in Cartagena.

Back in Etruria, the illness of her husband was carefully concealed from the population, as Maria Luisa alone was seen in public functions and entertaining at court. For this she was accused of overpowering her husband and being merry in his absence. Louis died on 27 May 1803, aged 30, as a consequence of an epileptic crisis.

Regent of Etruria

Grief-stricken by the death of her husband, she developed a nervous illness. She had to act as a regent for her son Charles Louis, the new King of Etruria. Only twenty years old when she was widowed, plans for a new wedding were considered: France and Spain wanted to marry her to her first cousin, Infante Pedro Carlos of Spain and Portugal, but the marriage never materialized.

During her four-year regency, Maria Luisa took on the government of Etruria with the help of her ministers Count Fossombroni and Jean Garbiel Eynard (1775-1863). With them, Maria Luisa reorganized the tax system, created taxable manufactures like tobacco and porcelain companies and increased the size of the army. The Queen regent spent lavishly on educational projects, founding a Higher School of Science, and the Museum of Physics and Natural History of Florence. To ingratiate herself with the Florentine people, she entertained lavishly at Pitti Palace, holding receptions for artists and writers, as well as government officials.

Though Maria Luisa by then had become fond of Florence, Napoleon had other plans for Italy and Spain: I am afraid the Queen is too young and her minister too old to govern the Kingdom of Etruria, he said. She was accused of not enforcing the English blockade in Etruria. Increasing Maria Luisa's isolation, Napoleon replaced the French ambassador to Etruria, the Marchaise de Beauharnais, with the less congenial, Count Hector d'Aubusson de la Feuillade, the Empress Josephine's chamberlain. On 23 November 1807, while Maria Luisa was staying at Castello, her country residence, the French minister came to inform her that Spain had ceded Etruria to France and ordered her to leave Florence on the spot. Her father answered her pleas with discouragement: she yielded and hastily left the kingdom, returning to her family in Spain, leaving Florence on 10 December 1807 with her children, their future uncertain. Napoleon annexed the territory to France and granted the title of "Grand Duchess of Tuscany" to his sister Elisa.

Exile

The exiled Queen went to Milan where she had an interview with Napoleon. He promised her, as compensation for the loss of Etruria, the throne of a Kingdom of Northern Lusitania (in the North of Portugal), he intended to create after the Franco-Spanish conquest of Portugal. This was part of the Treaty of Fontainebleau between France and Spain (October 1807) that also had incorporated Etruria to Napoleons' domains. Napoleon had already ordered the invasion of Portugal but his secret aim was ultimately to depose the Spanish royal family and have access to the money remitted from Spanish colonies in the New World. As part of the agreement, Maria Luisa would marry Lucien Bonaparte, who would have to divorce his wife, but both refused: Lucien was attached to his wife and Maria Luisa considered those nuptials a misalliance, and she would not allow herself to be put in Portugal in the place of her eldest sister, Carlota. Napoleon wanted Maria Luisa to settle in Nice or Turin, but her intentions were to join her parents in Spain. Crossing the south of France, on 3 February she entered Spain by Barcelona and on the 19th, she joined her family at Aranjuez. She arrived at a court deeply divided and a country in unrest: her brother, Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias, had plotted against their father and the unpopular prime minister Manuel Godoy.

Ferdinand had been pardoned but with the family's prestige shaken, Napoleon took this opportunity to invade Spain. With the excuse of sending reinforcements to Lisbon, French troops had entered Spain in December. Not completely blind to Napoleon's real intentions, the Spanish Royal family had secretly planned their escape to Mexico, but their plans were cut short. At this point Maria Luisa arrived in Aranjuez on 19 February 1808.

Supporters of Ferdinand spread the story that prime minister Godoy had betrayed Spain to Napoleon. On 18 March a popular uprising known as the Mutiny of Aranjuez took place. Members of popular classes, soldiers and peasants assaulted Godoy's residence, captured him, and made King Charles depose the prime minister. Two days later, the court forced Charles IV to abdicate and yield the throne to his son, now Ferdinand VII. The abdication of Charles IV in favor of Ferdinand VII was enthusiastically acclaimed by the people.

Maria Luisa, who at the time had been in Spain for barely a month, took her father's side against the party of her brother. She acted as intermediate between the deposed Charles IV and the French general Murat, who on 23 March entered Madrid. Napoleon, capitalizing on the rivalry between father and son, invited both to Bayonne, France, ostensibly to act as a mediator. Both kings, afraid of the French power, thought it appropriate to accept the invitation and separately left for France. Maria Luisa was just recovering from measles at the time of the Mutiny of Aranjuez, and was not fit to travel. Her son was also sick and she stayed behind with her children, her uncle Antonio and her younger brother Francisco de Paula. However, Napoleon insisted on all relatives of the King to leave Spain and called them to France. At their departure on 2 May 1808, citizens of Madrid rose up in rebellion against the French occupation, but the revolt was crushed by Murat.

At that time, Maria Luisa had become unpopular. The intervention in Etruria had been very costly to Spain and Maria Luisa secret dealing with Murat had been seen as going against the interest of her native country. She was considered in Spain as a foreign Princess aiming at gaining a throne for her son. Arriving at Bayonne, Maria Luisa was greeted by her father with the words "My daughter, our family has forever ceased to reign". Napoleon had forced both Charles IV and Ferdinand VII to renounce the throne of Spain and in exchange for their renunciation of all claims, were promised a large pension and residence in Compiegne and Château de Chambord. Maria Luisa, who in vain tried to convince Napoleon to restore her to Tuscany or Parma, was offered a large income. He assured her that she would be much happier without the troubles of government, but Maria Luisa openly protested against the confiscation of her son's dominions.

Imprisonment

After this, Napoleon gave Spain to his brother Joseph Bonaparte and forced the Royal family into exile in Fontainebleau. Maria Luisa requested a separate residence and moved with her children to a house in Passy, but was soon moved to Compiegne on 18 June. She was plagued by frequent sickness and shortage of money and, not owning any horses, was forced to walk wherever she needed to go. When at last Napoleon sent 12,000 francs as the promised compensation, the expenses of her trip to France were discounted. She wrote a letter of protest, saying that prisoners were never made to pay for their removal, but she was advised not to send it out. She was promised to retire to the Palace of Colorno in Parma with a substantial allowance, but once in Lyon, under the pretext of conducting her to her destination, she was escorted to Nice, where she was kept under strict vigilance.

She planned to escape to England, but her letters were intercepted and her two accomplices executed. Maria Luisa was arrested on 26 July and condemned to be imprisoned in a convent in Rome, while her nine-year-old son was to remain in the care of his grandfather Charles IV. Maria Luisa's pension was reduced to 2500 francs; all her jewels and valuables were taken away. She was imprisoned in the convent of Santi Domenico e Sisto, near the Quirinal on 14 August 1811 with her daughter and a maid. Her pleas for clemency were unanswered.

On 18 March 1812, Maria Luisa and her children were stripped of their rights to the Spanish crown by the Cortes of Cádiz – which served as a parliamentary Regency after Ferdinand VII was deposed – because she was under Napoleon's control. Her rights were not restored until 1820. The former Queen of Etruria wrote in her Memoirs:

I was for two years and a half in that monastery and one year without seeing or talking to anybody. I was not allowed to write or receive news not even from my own son. I had been in the convent for eleven months already when my parents came with my son to Rome on 16 June 1812. I was hoping to be released immediately after their arrival, but I was wrong, instead of diminishing the rigor of my imprisonment I was put under stricter orders.

On 19 June 1812, she was allowed to see her family. In an emotional meeting, Maria Luisa threw herself into her mother's arms, kissed her son with frenzy and her father hugged them all in a general embrace. After this, Maria Luisa was allowed to see her parents and her son once a month but only for twenty minutes and under surveillance. Only the fall of Napoleon opened the gates of her prison. On 14 January 1814, after more than four years of captivity, she was freed when the troops of Joachim Murat entered Rome.

Congress of Vienna

Maria Luisa moved with her children and her parents to the Barberini Palace. She hoped for the restorations of her son's estates and as the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) assembled to reorder the European map, she quickly wrote and published the Memoirs of the Queen of Etruria, originally written in Italian but translated to different languages, to put forward her case. When Napoleon returned from his exile at Elba, Maria Luisa and her parents fled Rome, moving from one city to another in Italy. The Countess de Boigne met her in Genoa and found her untidy and vulgar. When Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo, they returned to Rome.

At the Congress of Vienna, Maria Luisa's interests were represented by the Spanish emissary Marquis of Labrador, an incompetent man, who did not successfully advance his country's or Maria Luisa's diplomatic goals. The Austrian Minister Metternich had decided not to restore Parma to the House of Bourbon, but to give it to Napoleon's wife, Marie Louise of Austria. Maria Luisa pleaded her cause to her brother Ferdinand VII of Spain, the Pope, and Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Ultimately, the Congress decided to compensate Maria Luisa and her son with the smaller Duchy of Lucca, which was carved out of Tuscany. She was to retain the honors of a queen as she had before in Etruria. Her brother Ferdinand VII of Spain refused to sign both the Final act of the Congress and the subsequent Treaty of Paris of 1815.

Maria Luisa stubbornly rejected this compromise for more than two years. During this time, she lived with her children in a Roman palace. Family relationships became strained: her parents and her brother Ferdinand VII wanted to marry Maria Luisa's daughter, Maria Luisa Carlota, then fourteen years old, to Francisco de Paula, Maria Luisa's youngest brother. She opposed this plan, considering her brother (eight years older than her young daughter) to be too reckless. She also rejected a proposed plan for her own son to marry Maria Cristina of Naples, a daughter of her sister Maria Isabel.

Seeking independence from her family, Maria Luisa accepted the solution offered by the treaty of Paris in 1817: upon the death of Marie Louise of Austria, the duchy of Parma would revert "to H.M. the Infanta of Spain Maria Luisa, to the Infante D. Charles Louis her son and his direct male descendants". Maria Luisa became Duchess of Lucca in her own right (suo jure) and was granted the rank and privileges of a queen. Her son, Charles Louis, would succeed her only upon her death and would meantime be styled the Prince of Lucca. Lucca would be annexed to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany when the family regained possession of Parma. Then the Spanish minister in Turin, took possession of Lucca until Maria Luisa arrived on 7 December 1817.

Duchess of Lucca

When Maria Luisa arrived in Lucca, she was already thirty-five years old. Ten years of endless struggles had taken their toll: her youth was gone and she had gained a lot of weight. Nevertheless, she set her sights on a new marriage. She first addressed Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who was a widower, and also her first cousin, possibly with the idea of securing her position in Lucca and gaining a foothold in Florence. After this failed, she tried Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Este but this failed as well. After the assassination of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, in 1820, there were plans to marry her to his father, the future King Charles X of France.

Maria Luisa's firm intention was to obliterate every trace of the government of Elisa Bonaparte, who had ruled Lucca from 1805 to 1814 and who nominally succeeded Maria Luisa in Tuscany in 1808. As duchess, she promoted public works and culture in the spirit of enlightenment and during her government the sciences flourished. Between 1817 and 1820, she ordered the complete renewal of the inner decorations of the Palazzo Ducale, completely redecorating the building into its present form, making the Palazzo one of the finest in Italy. Maria Luisa, a religious woman, favored the clergy. In her small state, seventeen new convents were founded in the six years of her reign. Among the projects she accomplished were the building of a new aqueduct and the development of Viareggio, the port of the Duchy.

Politically, Maria Luisa disregarded the constitution imposed on her by the congress of Vienna and governed Lucca in an absolutist fashion, though her government was not very reactionary and oppressive. When the Spanish liberals imposed a constitution on her brother, King Ferdinand VII, she opened up to the idea of accepting a constitution, but the resurgence of Spanish absolutism in 1823 ended her intentions. In 1820, she arranged the wedding of her twenty-year-old son's with Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy, one of the twin daughters of King Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia. The relationship with her son had turned sour and later he complained that his mother had "ruined him physically, morally and financially".

Death

Throughout these years, she spent the summers in Lucca and the winters in Rome. She went to Rome on 25 October 1823 to her Palace in Piazza Venezia, already feeling ill. On 22 February 1824 she signed her will and died of cancer on 13 March 1824 in Rome. Her body was taken to Spain to be buried at the Escorial. A monument to her memory was erected in Lucca. Upon her death, she was succeeded by Charles Louis.

Children

Maria Luisa was survived by her two children:

- Charles Louis Ferdinand (22 December 1799 – 16 April 1883) married Maria Teresa of Savoy Princess of Savoy, daughter of King Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia and of Maria Theresa of Austria-Este.

- Luisa Carlota (Barcelona, 2 October 1802 – Rome, 18 March 1857) married Prince Maximilian of Saxony, widower of her aunt Carolina of Parma, as his second wife. Although the marriage was childless she was stepmother to Maximilian and Caroline's children, including the future kings Frederick Augustus II of Saxony and John I of Saxony, and Maria Josepha Amalia of Saxony, Queen of Spain

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Maria Luisa, Duchess of Lucca | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 91.

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 92.

- ^ Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 286.

- Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 90.

- Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 83.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 274.

- ^ Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 287.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 18.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 299.

- ^ Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 19.

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Memoir of the Queen of Etruria, pp. 3–4.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 15.

- ^ Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 510.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 27.

- ^ Mateos Sainz de Medrano, Ricardo. Los desconocidos infantes de Espana: Casa de Borbon (Spanish), pp. 91-97, Thassalia (1st edition 1996); ISBN 8482370545/ISBN 978-8482370545

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 302.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 303.

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Memoir of the Queen of Etruria, p.6.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 304.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 36.

- Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 511.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 43.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 48.

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Memoir of the Queen of Etruria, p. 9.

- Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 516.

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 93.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 69.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 70.

- ^ Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 71.

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Memoir of the Queen of Etruria, p. 13.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 74.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 78.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 79.

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 94.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 84.

- ^ Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 518.

- Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 519.

- ^ Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 523.

- ^ Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, p. 524.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 105.

- ^ Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 106.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 63-64.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 364.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 73.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 365.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 113.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 115.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 76.

- ^ Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 369.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 3705.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 132.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 134.

- ^ Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 373.

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 95.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 119.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 379.

- ^ Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 120.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 381.

- Smerdou, Carlos IV en el exilio , p. 187.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 383.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 121.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 122.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 127.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 133.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 143.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 155.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 86.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 87.

- Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 96.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 148.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 151.

- ^ Mateos, Los desconocidos infantes de España, p. 97.

- Bearne, A Royal Quartette, p. 384.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 153.

- Marques de Villa-Urrutia, La Reina de Etruria, p. 154.

- Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. pp. 9, 96.

References

- Balansó, Juan. La Familia Rival. Barcelona, Planeta, 1994. ISBN 978-8408012474

- Balansó, Juan. Las Perlas de la Corona. Barcelona, Plaza & Janés, 1999. ISBN 978-8401540714

- Bearne, Catherine Mary Charlton. A Royal Quartette: Maria Luisa, Infanta of Spain. Brentano's, 1908. ASIN: B07R12B4NQ

- Davies, Norman. Vanished Kingdoms: The Rise and fall of States and Nations. New York, Viking, 2011. ISBN 978-0-670-02273-1

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Duchess of Lucca. Memoir of the Queen of Etruria. London, John Murray, 1814. ISBN 978-1247377858

- Mateos Sainz de Medrano, Ricardo. Los desconocidos infantes de España. Thassalia, 1996. ISBN 8482370545

- Sixtus, Prince of Bourbon-Parma. La Reine d'Étrurie. Paris, Calmann-Levy, 1928. ASIN: B003UAFSSG

- Smerdou Altoaguirre, Luis. Carlos IV en el Exilio. Pamplona, Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, 2000. ISBN 978-8431318314

- Villa-Urrutia, W. R Marques de. La Reina de Etruria: Doña Maria Luisa de Borbón Infanta de España. Madrid, Francisco Beltrán, 1923. ASIN: B072FJ4VJ6

| Maria Luisa, Duchess of Lucca House of BourbonCadet branch of the Capetian dynastyBorn: 6 July 1782 Died: 13 March 1824 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byElisa Bonaparteas princess | Duchess of Lucca 1815–1824 |

Succeeded byCharles I |

| Infantas of Spain | |

|---|---|

| Generations indicate descent from Carlos I, under whom the crowns of Castile and Aragon were united, forming the Kingdom of Spain. | |

| 1st generation | |

| 2nd generation | |

| 3rd generation | |

| 4th generation | |

| 5th generation |

|

| 6th generation |

|

| 7th generation | |

| 8th generation | |

| 9th generation | |

| 10th generation |

|

| 11th generation | |

| 12th generation | |

| 13th generation | |

| 14th generation | |

| 15th generation | |

| 16th generation | |

| *title granted by Royal Decree | |

| Princesses of Parma by marriage | |

|---|---|

| Generations are numbered from the daughter-in-law of Pier Luigi Farnese, Duke of Parma, onwards | |

| 1st generation | |

| 2nd generation | |

| 5th generation |

|

| 6th generation | |

| 7th generation |

|

| 8th generation |

|

| 10th generation | |

| 11th generation | |

| 12th generation | |

| 13th generation | |

| 14th generation | |

| 15th generation | |

| 16th generation | |

| *did not have a royal or noble title by birth ^also princess of Luxembourg by marriage ¤also princess of Nassau by marriage #title lost due to divorce | |

- 1782 births

- 1824 deaths

- 18th-century Spanish people

- 18th-century Spanish women

- 19th-century Spanish writers

- 19th-century Spanish women writers

- 19th-century women regents

- 19th-century regents

- 19th-century women monarchs

- 19th-century memoirists

- People from the Province of Segovia

- Duchesses in Italy

- Regents of Parma

- Princesses of Bourbon-Parma

- Spanish infantas

- Burials in the Pantheon of Infantes at El Escorial

- Deaths from cancer in Lazio

- People from the Duchy of Lucca

- Daughters of kings

- Queen mothers

- Children of Charles IV of Spain