Mental substance, according to the idea held by dualists and idealists, is a non-physical substance of which minds are composed. This substance is often referred to as consciousness.

This is opposed to the materialists, who hold that what we normally think of as mental substance is ultimately physical matter (i.e., brains).

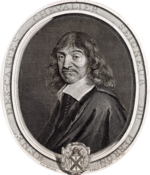

Descartes, who was most famous for the assertion "I think therefore I am", has had a lot of influence on the mind–body problem. He describes his theory of mental substance (which he calls res cogitans distinguishing it from the res extensa) in the Second Meditation (II.8) and in Principia Philosophiae (2.002).

He used a more precise definition of the word "substance" than is currently popular: that a substance is something which can exist without the existence of any other substance. For many philosophers, this word or the phrase "mental substance" has a special meaning.

Gottfried Leibniz, belonging to the generation immediately after Descartes, held the position that the mental world was built up by monads, mental objects that are not part of the physical world (see Monadology).

According to Descartes, God first created eternal truths and then the world from nothing, governing it with His divine providence. He took special care of human creatures, placing innate ideas in their thought, starting with the ideas of perfection and infinity.

The distinction between res cogitans and res extensa was taken up in Spinoza's Ethics, according to which Thought and Extension are two infinite attributes of the one divine Substance. Soul and body are in turn two finite modes of Thought and Extension.

See also

- Dualism (philosophy of mind)

- Monadology

- Monism

- Pluralism (philosophy of mind)

- Johannes Jacobus Poortman

References

- Father Battista Mondin, O.P. (2022). Ontologia e metafisica [Ontology and metaphysics]. Filosofia (in Italian) (3rd ed.). Edizioni Studio Domenicano. p. 59. ISBN 978-88-5545-053-9.