| Mercury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | François Duquesnoy |

| Year | 1630s |

| Type | Sculpture |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Subject | Mercury |

| Dimensions | 63 cm (24.8 in) |

| Location | Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna |

| Coordinates | 48°13′21″N 16°21′34″E / 48.22250°N 16.35944°E / 48.22250; 16.35944 |

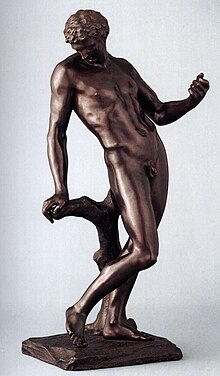

Mercury is a bronze sculpture of the god Mercury by the Flemish sculptor François Duquesnoy. It was likely cast in the 1630s, but certainly before 1636, when an engraving of the sculpture was produced in Rome.

The bronze is currently part of the private collection of the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna. Another bronze by Duquesnoy of about the same size, and dating to the same period, the Apollo and Cupid, is likewise housed at the Liechtenstein Museum.

Background

The sculpture was commissioned from Duquesnoy by Vincenzo Giustiniani, a frequent commissioner for Duquesnoy and a friend of his. In the 1630s, Giustiniani helped Duquesnoy finishing one of his masterpieces (the Saint Andrew) by advancing Duquesnoy 300 scudi for a sculpture of the Virgin he commissioned from the Fiammingo.

Giustiniani was of Greek origin, and a lover of Ancient sculpture and Greek art. He therefore was a supporter of a revival of the Greek style, and found in Duquesnoy (perhaps the most prominent exponent of the group of traditionalist artists in Rome) and his Greek Ideal a perfect artist to patronize. His commission of the Mercury (or Hermes) from Duquesnoy emphasizes Giustiniani's enthusiasm for Duquesnoy's maniera greca and the revival of the Greek style.

Background

According to Giovanni Pietro Bellori, the sculpture was originally designed as a pendant to a bronze of Hercules in possession of Giustiniani. In Bellori's Vita delli musei, said Herlucs, Duquesnoy's Mercury, and a sculpture of Athena are described as the highlights of Giustiniani collection. In a 1638 inventory, the Hercules and Duquesnoy's Mercury are reported as standing side by side on the same table.

Mercury his standing up, resting his right hand on a tree stump while gracefully bending his body to the right. He is bending his knee to the left in elegant pose. Mercury leans back to look at an infant putto tying wings at his feet. However, the original cupid, or amorino, is now lost.

Duquesnoy's Mercury testifies to his vision and own interpretation of valuable Greek sculpture. Among Duquesnoy's precepts, there were the toned slimness and the seemingly manneristic extent lengthwise of limbs. Both features are evident in the Mercury.

The Austrian sculptor Georg Rafael Donner greatly admired Duquesnoy's Mercury and his Apollo and Cupid. Duquesnoy's authorship was forgotten in the eighteenth century, and the work was thought to be an antique. The Mercury was among the ancient sculptures which Donner admired and copied, although in fact the bronze wasn't ancient at all.

References

- ^ Lingo, Estelle Cecile (2007). François Duquesnoy and the Greek Ideal. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 37–42, 65, 173. ISBN 9780300124835.

- ^ "François Duquesnoy Mercury". Liechtenstein Museum. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Mercury". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Lingo, Estelle (2002). "The Greek Manner and a Christian "Canon": François Duquesnoy's "Saint Susanna"". The Art Bulletin. 84 (1). The Art Bulletin (Vol. 84, No. 1) via jstor: 65–93. doi:10.2307/3177253. JSTOR 3177253.

Sources

- Fransolet, Mariette (1942). Francois du Quesnoy, sculpteur d'Urbain VIII, 1597-1643. Bruxelles, Belgium: Academie Royale de Belgique.

- Lingo, Estelle (2002). "The Greek Manner and a Christian "Canon": François Duquesnoy's "Saint Susanna"". The Art Bulletin. 84 (1). The Art Bulletin (Vol. 84, No. 1) via jstor: 65–93. doi:10.2307/3177253. JSTOR 3177253.

- Lingo, Estelle Cecile (2007). François Duquesnoy and the Greek Ideal. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300124835.

- Boudon-Machuel, Marion (2005). François Du Quesnoy. Paris, France: Arthena.

External links

- Duquesnoy's Mercury at Liechtenstein Museum official website

- Duquesnoy's Mercury at the Web Gallery of Art

| François Duquesnoy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sculpture |

|  | ||||||