| Mississippi kite | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Oklahoma, USA | |

| Conservation status | |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Ictinia |

| Species: | I. mississippiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ictinia mississippiensis (Wilson, A, 1811) | |

| |

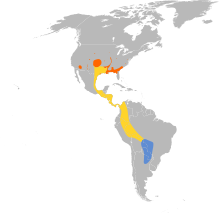

| Breeding Nonbreeding Migration | |

The Mississippi kite (Ictinia mississippiensis) is a small bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. Mississippi kites have narrow, pointed wings and are graceful in flight, often appearing to float in the air. It is common to see several circling in the same area.

Taxonomy

The Mississippi kite was first named and described by the Scottish ornithologist Alexander Wilson in 1811, in the third volume of his American Ornithology. Wilson gave the kite the Latin binomial name of Falco mississippiensis: Falco means "falcon", while mississippiensis means from the Mississippi River in the United States. The current genus of Ictinia originated with Louis Pierre Vieillot's 1816 Analyse d'une nouvelle Ornithologie Elémentaire. The genus name derives from the Greek iktinos, for "kite". Wilson also gave the Mississippi kite its English-language common name. He had first observed the species in the Mississippi Territory, while the bird's long pointed wings and forked tail suggested that it was a type of kite. It is currently classified in the subfamily Buteoninae, tribe Buteonini.

Description

Adults are gray with darker gray on their tail feathers and outer wings and lighter gray on their heads and inner wings. Kites of all ages have red eyes and red to yellow legs. Males and females look alike, but the males are slightly paler on the head and neck. Young kites have banded tails and streaked bodies. The bird is 12 to 15 inches (30–37 cm) beak to tail and has a wingspan averaging 3 feet (91 cm). Weight is from 214 to 388 grams (7.6–13.7 oz). The call is a high-pitched squeak, sounding similar to the noise made by a squeaky toy.

Range and migration

The summer breeding territory of the Mississippi kite is in the Central and Southern United States; the southern Great Plains is considered a stronghold for the species. Sightings are frequently documented across many states, including Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. Breeding territories have seemingly expanded during the early 21st century, with the kites having been regularly recorded from Southern California to the southern reaches of New England; in 2008, a pair successfully bred and raised chicks near Newmarket, New Hampshire. The year prior, another pair was observed breeding in Ohio, in 2007. The species has also been documented as far north as Canso, Nova Scotia. Indeed, the species' territory has expanded west due to the creation of shelterbelts (similar to hedgerows), usually planted in grassland habitats, providing shelter and food for numerous birds.

This Mississippi kite migrates to subtropical and temperate regions of South America for the winter, mostly to northern Argentina and southern Brazil. They are also known from Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, México, and Panamá. Migration normally occurs in groups of 20 to 30 birds. However, there are exceptions, as mixed flocks may occur; groups of up to 10,000 birds at one time may be observed, such as at Fuerte Esperanza, Argentina.

Behavior and ecology

Mississippi kites are social raptors, gathering in roosts in late summer. They do not maintain strict territories.

Food and feeding

The diet of the Mississippi kite consists mostly of larger-bodied invertebrates and insects (which they capture in-flight), seasonally feeding on a variety of cicadas, crickets, grasshoppers and locusts and other crop-damaging insects, making them agriculturally and economically beneficial for humans. As with most raptors, the Mississippi kite is an opportunistic hunter, and has also been known to capture small vertebrates, including passerine birds, amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals. They will usually hunt from a low perch before pursuing prey, consuming it in-flight upon capture. They will often patrol around herds of livestock or grazing wild ungulates (such as bison or wapiti), to catch insects stirred-up from the ground.

Breeding

Mississippi kites are monogamous, forming breeding pairs before, or soon after, arriving at breeding sites. Courtship displays are rare, however individuals have been seen guarding their mate from competitors.

Mississippi kites usually lay two white eggs (rarely one or three) in twig-constructed nests that rest in a variety of deciduous trees, most commonly elm, eastern cottonwood, hackberry, oak or mesquite; other than within elm and cottonwood trees, most nests are less than 20 feet (6 m) above the ground, and are usually near water. Eggs are white to pale-bluish in color, and are usually about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) long. For the past 75 years, the species has experienced changes in nesting habitat, adapting from open forest and savanna to include hedgerows and shelterbelts, and is now a common nester in urban areas in the western south-central states.

Mississippi kites nest in colonies. Both parents incubate the eggs and care for the young. They have one clutch a year, which takes 30 to 32 days to hatch. The young birds leave the nest just 30 to 34 days after hatching. Only about 50 percent of broods succeed. As with many birds, mortality rates are high, as both eggs and chicks may fall victim to high winds, storms, or predators such as mustelids, opossums, raccoons and owls. As there are typically fewer arboreal predators in urban areas (besides domestic or feral cats and raccoons), Mississippi kites breed more successfully in human-populated areas than in more rural locales. They have an average lifespan of 8 years.

Conservation

The species was in-decline in the mid-1900s, but now has an increasing population and expanding range. While the Mississippi kite is not an endangered species, it is protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which protects the birds, their eggs, and their nests (occupied or empty) from being moved or tampered with without the proper permits. This can make the bird a nuisance when it chooses to roost in populated urban spots such as golf courses or schools. Mississippi kites protect their nests by diving at perceived threats, including humans; however, this occurs in less than 20% of nests. Staying at least 50 yards from nests is the best way to avoid conflict with the birds. If this is not possible, wearing a hat or waving hands in the air should prevent the bird from making contact but will not prevent the diving behavior.

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Ictinia mississippiensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22695066A93488215. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695066A93488215.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Alexander (1811). American ornithology, or, The natural history of the birds of the United States. Vol. III. Philadelphia, PA: Bradford and Inskeep. pp. 80–82. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.97204. LCCN 11004314. OCLC 4961598.

- Burns, Frank L. (1909). "Alexander Wilson. VI: His Nomenclature". The Wilson Bulletin. 21 (3): 132–151. JSTOR 4154253.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 157, 202, 257. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Vieillot, Louis Pierre (1883). Saunders, Howard (ed.). Analyse d'une nouvelle Ornithologie Elémentaire (in French). London: Taylor and Francis. p. 24. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.12613. OCLC 8055739.

- Mindell, David P.; Fuchs, Jérôme; Johnson, Jeff A. (2018). "Phylogeny, taxonomy, and geographic diversity of diurnal raptors: Falconiformes, Accipitriformes, and Cathartiformes". In Sarasola, José Hernán; Grande, Juan Manuel; Negro, Juan José (eds.). Birds of Prey: Biology and Conservation in the XXI Century. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 3–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73745-4_1. ISBN 978-3-319-73745-4.

- ^ "Ictinia mississippiensis (Mississippi kite)". Animal Diversity Web. Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan. Retrieved 15 Mar 2022.

- Udvardy, Miklos D. F.; Farrand Jr., John (1994). National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds Western Region. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 349–350. ISBN 0-679-42851-8.

- ^ Andelt, William F. (1994), "Mississippi Kites" (PDF), Internet Center for Wildlife and Damage Management, handbook: E76, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13, retrieved 2008-08-20

- ^ Ictinia mississippiensis, iNaturalist - Mississippi kite (2 December 2024). "Observations - iNaturalist".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Bird Unseen in N.H. Spotted in Newmarket", WMUR-TV, ["Bird Unseen in N.H. Spotted in Newmarket - Family News Story - WMUR New Hampshire". Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "Mississippi kite". The Peregrine Fund. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ^ "Mississippi kite (Ictinia mississippiensis)". Texas Parks & Wildlife. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- "Mississippi kite". The Texas Breeding Bird Atlas. Texas A&M AgriLife Research. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- Birds Protected Under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act (PDF)

External links

- Mississippi Kite - Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center Article

- Mississippi kite videos on the Internet Bird Collection

Historical material

- "Falco Mississippiensis, Mississippi Kite"; in American Ornithology 2nd edition, volume 1 (1828) by Alexander Wilson and George Ord. Colour plate from 1st edition by A. Wilson.

- John James Audubon. "The Mississippi Kite", Ornithological Biography volume 2 (1834). Illustration from Birds of America octavo edition, 1840.

- "Mississippi Kite", Thomas Nuttall, A manual of the ornithology of the United States and of Canada; volume 1, The Land Birds (1832).

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Ictinia mississippiensis |

|