50°42′24″N 0°46′28″W / 50.70666667°N 0.77444444°W / 50.70666667; -0.77444444

The Mixon (reef, rocks or shoal) are a limestone outcrop in the English Channel about 1 mile (1,600 m) off Selsey Bill, West Sussex. It was formed during the Eocene period.

At the east end of the reef is a gully with a depth of 30 meters (98 ft). Known as the "Mixon Hole", this feature makes up the north side of a drowned river gorge. The Mixon is part of a Marine Conservation Zone and supports diverse wildlife including short-snouted seahorses, squat lobsters and crabs along with red algae and kelp in shallower waters. The Mixon Hole is a popular destination for scuba divers. Rock from the Mixon has been quarried at least from Roman times till the 19th century and used in the local building industry.

The reef has been a major hazard to shipping over the centuries, with stories of wrecks dating from medieval times.

Name

The name Mixon probably is derived from the Old English: mixen meaning 'dunghill'. It is thought that dung from bullocks was stored in this area during the Anglo-Saxon period.

History

The exact configuration of the coastline in the early Holocene is not precisely known, but the Mixon and other reefs in the area that were formed within the sands and silts of the Bracklesham Group are thought to have significantly shaped the palaeogeographic landscape and protected against coastal erosion.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Mixon would have been the shoreline during the Roman occupation, and was not breached by the sea until the 10th or 11th century.

Barrier breaching and shoreline recession associated with rising sea-level and storm events caused the Mixon to become an offshore bank, or shoal, probably at about 950–1050

— SCOPAC 2003

The Mixon rocks have been a great hazard to shipping vessels over the centuries. The cartographer John Speed placed the Mixon (incorrectly), off the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight on his 1610 map. Probably the earliest sailing directions about this area are in the "Great Britains Coasting Pilot" for 1693, where the author Greenvile Collins writes of the Mixon and Owers shoals:

I will not give any directions to sail through them, nor within them. There lye some other banks within them, which I forbear to speak of them. The only and chief end of my business is to give good directions how to avoid these shoals, that have proved fatal to so many ships.

— Collins 1693, p. 3

To warn shipping vessels of the dangerous Mixon and Owers shoals, a light vessel was anchored off the Mixon in 1788 by Trinity House. From that date onward a series of vessels have been used for the same purpose, and between 1939 and 1973 the commonly-used craft was lightship number 3. In 1973 the lightship was replaced with a beacon and then from 2015 a South Cardinal was installed.

The Mixon rock has been quarried at least since the Roman occupation of the area and became an important building stone in the late Saxon period. There is evidence of its use mainly on the Manhood Peninsula but also within an area bounded by Westbourne, Westhampnett, Oving and South Bersted. Quarrying ceased after an Admiralty prohibition order in 1827. Some examples of structures where Mixon stone was used are the Fishbourne Roman Palace and the Hayling Island Bridge.

In the 19th century, the "Channel Pilot" recorded the presence of a deep hole at the eastern end of the reef. Known as the Mixon Hole, the depression is approximately 8 Fathoms deep. More recently the Mixon Hole has been described as the "most dramatic underwater cliff in the channel".

The great depth of the Mixon hole, plus it being relatively near to the shore, has made it a popular dive site.

Marine life

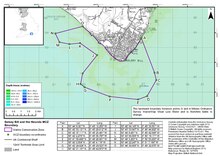

The crevices and ledges within the Mixon Hole provide a habitat for a variety of marine species including short-snouted seahorses, squat lobsters and crabs, along with red algae. The short-snouted seahorse is protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 of the United Kingdom and by CITES. The UK Government established Marine Conservation Zones(MCZ) to protect the populations and habitats of rare or threatened species. The Mixon is within the Selsey Bill and the Hounds MCZ that was designated on the 31 May 2019. It has an area of around 16 square kilometres (6.2 sq mi)

Short-snouted seahorse

Short-snouted seahorse Squat lobster

Squat lobster Red algaeExamples of marine life found on the Mixon

Red algaeExamples of marine life found on the Mixon

Geology

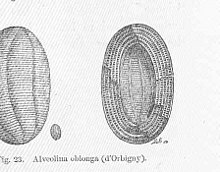

Mixon Rock is a tough, coarse-grained, pale grey to honeyyellow bioclastic limestone or calcareous sandstone. This stone belongs to the Bracklesham Group that was formed about 45 million years ago. The stone itself has been formally named by geologists as "Mixon Rock". The rock contains microfossils, such as Foraminifera, along with shell debris, sponge spicules and echinoid spines, some corals, bryozoans and shark teeth. It also contains scattered sand grains and glauconite.The Mixon is only one of three localities in the United Kingdom where an extinct genus of Foraminifera known as Alveolina can be found.

The north face of the Mixon Hole is a clay cliff that is vertical in its upper parts to between 5 and 20 metres below sea level. At the top of the cliff limestone overlies softer grey clay. The Mixon Hole forms the north side of a drowned river gorge which is kept open by the strong tidal currents through it.

At the base of the hole a mixture of boulders and cobbles of both clay and limestone has fallen from the cliff above. Away from the cliff on the seabed there is a preponderance of empty slipper limpet shells.

Folklore, myths and legends

There are many myths and legends associated with The Mixon. For example, the foundation story of Sussex as recorded in the "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" tells how the Anglo-Saxon king Ælle and his three sons landed at a place called Cymenshore in AD 477. The modern location for Cymenshore has been lost although the written evidence suggests that it was located at The Mixon.However most academics agree that although it is possible that Cymenshore existed, the foundation story itself is a myth.

Another more recent example is a custom that suggests that the dead should be placed, in their coffins, on Selsey beach at night. In the morning the coffins would be gone — and it was said that the people of the sea had taken them to the Mixon Hole. A more plausible explanation is that abandoning coffins here was associated with smuggling. A coffin full of contraband would be deposited on the beach, ready to be picked up and distributed by a coastal cutter, and because it seemed to be a funeral rite this practice would not attract the attention of the customs official.

See also

Notes

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how raiding Vikings had their ships flounder on the rocks.

- There had been sketches and maps of the area over several centuries, for example Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer's Spiegel der Zeevaert, charted the area but had not provided directions.

- 8 Fathoms: 48 feet (15 m)

- 2 kilometres (1.2 mi)

Citations

- Richardson 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Bone & Bone 2014.

- Krawiec 2017, pp. 101–112.

- Lavelle 2010, pp. 290–293.

- Mee 1988, Chapter 7.

- Richardson 2000, p. 75.

- Headrick 2000, p. 113.

- United Kingdom Hydrographic Office 2004, (SC1652) Selsey Bill to Beachy Head.

- Mee 1988, p. 64.

- Trinity House 2015.

- ^ King 2023, p. 31.

- English Channel Pilot 1878, p. 36.

- Wood 1988, p. 47.

- Irving 1995.

- ^ Sussex Wildlife Trust 2023.

- UK Government 2023.

- Natural England 2019.

- Adams 1962.

- ^ The Geological Society 2012.

- ^ O'Leary 2013, pp. 23–26.

- Richardson 2000, p. 64.

- Lapidge 2001, pp. 35–36.

- Welch 1978, pp. 13–35.

- Halsall 2013, p. 71.

References

- Adams, C. G. (1962). "Alveolina from the Eocene of England". Micropaleontology. 8 (1): 45–54. Bibcode:1962MiPal...8...45A. doi:10.2307/1484394. JSTOR 1484394.

- Bone, David; Bone, Anne (2014). Barber, Luke (ed.). "Quarrying the Mixon Reef at Selsey, West Sussex". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 152. Sussex Archaeological Society: 95–116. doi:10.5284/1086037.

- Collins, Greenville (1693). Great Britains Coasting Pilot. London: Freeman Collins. OCLC 561288352.

- English Channel Pilot (1878). The English channel pilot, compiled from the latest surveys. London: Charles Wilson. OCLC 79661070.

- The Geological Society (2012). "Mixon Hole Deep Water Gully". Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- Halsall, Guy (2013). Worlds of Arthur: Facts and Fictions of the Dark Ages. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-965817-6.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (2000). When information came of age. OUP. ISBN 978-0195-13597-8.

- Irving, Robert (1995). "The Mixon Hole". Sussex Marine Sites of Nature Conservation Importance. Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- King, Andy (2023), Historic England 2023 West Sussex. Building Stones of England, Swindon: Historic England, archived from the original on 13 February 2024, retrieved 13 February 2024

- Krawiec, Kristina (June 2017). "Medmerry, West Sussex, UK: Coastal Evolution from the Neolithic to the Medieval Period and Community Resilience to Environmental Change". Historic Environment: Policy & Practice. 8 (2): 101–112. doi:10.1080/17567505.2017.1317081.

- Lapidge, Michael; et al. (2001). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Lavelle, Ryan (2010). Alfred's Wars Sources and Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-569-1.

- Mee, Frances (1988). A History of Selsey. Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-672-4.

- Natural England (2019). "Selsey Bill and the Hounds MCZ" (PDF). UK Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- O'Leary, Michael (2013). Sussex Folk Tales. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7469-4.

- SCOPAC (2003). "East Head to Pagham Harbour, West Sussex" (PDF). SCOPAC Sediment Transport Study. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- Sussex Wildlife Trust (2023). "Selsey Bill & The Hounds". Henfield, West Sussex. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- Trinity House (6 July 2015), 21-15 Mixon Beacon: Trinity House Notice to Mariners, London: Trinity House, archived from the original on 27 November 2024, retrieved 13 February 2024

- United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (2004). (SC1652) Selsey Bill to Beachy Head (Map). United Kingdom Hydrographic Office. ISBN 1-84579-317-X.

- UK Government (13 June 2023). "Guidance: Seahorses". London: Marine Management Organisataion. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- Richardson, W.A.R. (2000). Watts, Victor (ed.). "The Owers". The English Placename Society Journal 33. ISSN 1351-3095.

- Welch, M.G. (1978). "Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex". In Brandon, Peter (ed.). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-240-0.

- Wood, Elizabeth M, ed. (1988). Sea life of Britain and Ireland. London: Immel. ISBN 0-907151-33-7.