The Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC, also known as the Edison Trust), founded in December 1908 and effectively terminated in 1915 after it lost a federal antitrust suit, was a trust of all the major US film companies and local foreign-branches (Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Selig Polyscope, Lubin Manufacturing, Kalem Company, Star Film Paris, American Pathé), the leading film distributor (George Kleine) and the biggest supplier of raw film stock, Eastman Kodak. The MPPC ended the domination of foreign films on US screens, standardized the manner in which films were distributed and exhibited within the US, and improved the quality of US motion pictures by internal competition. It also discouraged its members' entry into feature film production, and the use of outside financing, both to its members' eventual detriment.

Creation

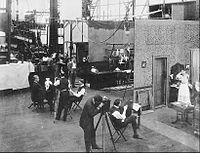

The MPPC was preceded by the Edison licensing system, in effect in 1907–1908, on which the MPPC was modeled. During the 1890s, Thomas Edison owned most of the major US patents relating to motion picture cameras. The Edison Manufacturing Company's patent lawsuits against each of its domestic competitors crippled the US film industry, reducing production mainly to two companies: Edison and Biograph, which used a different camera design. This left Edison's other rivals with little recourse but to import French and British films.

Since 1902, Edison had also been notifying distributors and exhibitors that if they did not use Edison machines and films exclusively, they would be subject to litigation for supporting filmmaking that infringed Edison's patents. Exhausted by the lawsuits, Edison's competitors — Essanay, Kalem, Pathé Frères, Selig, and Vitagraph — approached him in 1907 to negotiate a licensing agreement, which Lubin was also invited to join. The one notable filmmaker excluded from the licensing agreement was Biograph, which Edison hoped to squeeze out of the market. No further applicants could become licensees. The purpose of the licensing agreement, according to an Edison lawyer, was to "preserve the business of present manufacturers and not to throw the field open to all competitors."

In February 1909, major European producers held the Paris Film Congress in an attempt to create a similar European organisation. This group also included MPPC members Pathé and Vitagraph, which had extensive European production and distribution interests. This proposed European cartel ultimately failed when Pathé, then still the largest company in the world, withdrew in April.

The addition of Biograph

Biograph retaliated for being frozen out of the trust agreement by purchasing the patent to the Latham film loop, a key feature of virtually all motion picture cameras then in use. Edison sued to gain control of the patent. After a federal court upheld the validity of the patent in 1907, Edison began negotiation with Biograph in May 1908 to reorganize the Edison licensing system. The resulting trust pooled 16 motion picture patents. Ten were considered of minor importance. The remaining six pertained one each to films, cameras, and the Latham loop, and three to projectors.

Policies

The MPPC eliminated the outright sale of films to distributors and exhibitors, replacing it with rentals, which allowed quality control over prints that had formerly been exhibited long past their prime. The trust also established a uniform rental rate for all licensed films, thereby removing price as a factor for the exhibitor in film selection, in favor of selection made on quality, which in turn encouraged the upgrading of production values.

The MPPC also established a monopoly on all aspects of filmmaking. Eastman Kodak owned the patent on raw film stock, and the company was a member of the trust and thus agreed to sell stock only to other members. Likewise, the trust's control of patents on motion picture cameras ensured that only MPPC studios were able to film, and the projector patents allowed the trust to make licensing agreements with distributors and theaters – and thus determine who screened their films and where.

The patents owned by the MPPC allowed them to use federal law enforcement officials to enforce their licensing agreements and to prevent unauthorized use of their cameras, films, projectors, and other equipment. In some cases, the MPPC made use of hired thugs and mob connections to violently disrupt productions that were not licensed by the trust.

Content

The MPPC also strictly regulated the production content of their films, primarily as a means of cost control. Films were initially limited to one reel in length (13–17 minutes), although competition by independent and foreign producers by 1912 led to the introduction of two-reelers, and by 1913, three and four-reelers.

Backlash and decline

Many independent filmmakers, who controlled from one-quarter to one-third of the domestic marketplace, responded to the creation of the MPPC by moving their operations to Hollywood, whose distance from Edison's home base of New Jersey made it more difficult for the MPPC to enforce its patents. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is headquartered in San Francisco, California, and covers the area, was averse to enforcing patent claims. Southern California was also chosen because of its beautiful year-round weather and varied countryside; its topography, semi-arid climate and widespread irrigation gave its landscapes the ability to offer motion picture shooting scenes set in deserts, jungles and great mountains. Hollywood had one additional advantage: if a non-licensed studio was sued, it was only a hundred miles to "run for the border" and get out of the US to Mexico, where the trust's patents were not in effect and thus equipment could not be seized.

The reasons for the MPPC's decline are manifold. The first blow came in 1911 when Eastman Kodak modified its exclusive contract with the MPPC to allow Kodak, which led the industry in quality and price, to sell its raw film stock to unlicensed independents. The number of theaters exhibiting independent films grew by 33 percent within twelve months, to half of all houses.

Another reason was the MPPC's overestimation of the efficiency of controlling the motion picture industry through patent litigation and the exclusion of independents from licensing. The slow process of using detectives to investigate patent infringements, and of obtaining injunctions against the infringers, was outpaced by the dynamic rise of new companies in diverse locations.

Despite the rise in popularity of feature films in 1912–1913 from independent producers and foreign imports, the MPPC was very reluctant to make the changes necessary to distribute such longer films. Edison, Biograph, Essanay, and Vitagraph did not release their first features until 1914, after dozens, if not hundreds, of feature films, had been released by independents.

Patent royalties to the MPPC ended in September 1913 with the expiration of the last of the patents filed in the mid-1890s at the dawn of commercial film production and exhibition. Thus the MPPC lost the ability to control the American film industry through patent licensing and had to rely instead on its subsidiary, the General Film Company, formed in 1910, which monopolized film distribution in US.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 cut off most of the European market, which played a much more significant part of the revenue and profit for MPPC members than for the independents, which concentrated on Westerns produced for a primarily US market.

The end came with a federal court decision in United States v. Motion Picture Patents Co. on October 1, 1915, which ruled that the MPPC's acts went "far beyond what was necessary to protect the use of patents or the monopoly which went with them" and was, therefore, an illegal restraint of trade under the Sherman Antitrust Act. An appellate court dismissed the MPPC's appeal, and officially terminated the company in 1918.

See also

References

- Edison v. American Mutoscope & Biograph Co., 151 F. 767 (2d. Cir. 1907).

- ^ U.S. v. Motion Picture Patents Co., 225 F. 800 (E.D. Pa. 1915).

- Bach, Steven (1999). Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film that Sank United Artists. New York: Newmarket Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-55-704374-0.

- Projection speeds ranged from 16 to 20 frames per second.

- For example, the four-reelers From the Manger to the Cross (Kalem, 1913), The Battle of Shiloh (Lubin, 1913), and The Third Degree (Lubin, 1913).

- Edidin, Peter (August 21, 2005). "La-La Land: The Origins". The New York Times. p. 4.2.

Los Angeles's distance from New York was also comforting to independent film producers, making it easier for them to avoid being harassed or sued by the Motion Picture Patents Company, AKA the Trust, which Thomas Edison helped create in 1909.

- e.g., Zan v. Mackenzie, 80 F. 732 (9th Cir. 1897)., Germain v. Wilgus, 67 F. 597 (9th Cir. 1895). and Johnson Co. v. Pac. Rolling Mills Co., 51 F. 762 (9th Cir. 1892)..

- Per the American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures, 8 US features were released in 1912, 61 in 1913, and 354 in 1914.

- "Orders Movie Trust to be Broken Up" (PDF). The New York Times. October 2, 1915.

Further reading

- Thomas, Jeanne (Spring 1971). "The Decay of the Motion Picture Patents Company". Cinema Journal. 10 (2): 34–40. doi:10.2307/1225236. JSTOR 1225236.

External links

- Before the Nickelodeon: Motion Picture Patents Company Agreements

- History of Edison Motion Pictures: Litigation and Licensees

- Independence In Early And Silent American Cinema

- Armando Franco (May 11, 2004). "The Motion Picture Patents Company vs. The Independent Outlaws" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-02.

| Thomas Edison | |

|---|---|

| Discoveries and inventions | |

| Advancements | |

| Ventures |

|

| Monuments | |

| Family |

|

| Films |

|

| Literature |

|

| Productions |

|

| Terms | |

| Related | |