A motorcycle helmet is a type of helmet used by motorcycle riders. Motorcycle helmets contribute to motorcycle safety by protecting the rider's head in the event of an impact. They reduce the risk of head injury by 69% and the risk of death by 42%. Their use is required by law in many countries. However, only 10.4% of all motorcyclists wear helmets, according to the World Health Organization in 2016.

Motorcycle helmets consist of a polystyrene foam inner shell that absorbs the shock of an impact, and a protective plastic outer layer. Several variations exist, notably helmets that cover the chin area and helmets that do not. Some helmets provide additional conveniences, such as ventilation, face shields, sun visors, ear protection or intercom.

Origins

The origins of the crash helmet date back to the Brooklands race track in early 1914, when a medical officer, Dr. Eric Gardner, noticed he was seeing a motor cyclist with head injuries about every two weeks. He got a Mr. Moss of Bethnal Green to make canvas and shellac helmets stiff enough to stand a heavy blow and smooth enough to glance off any projections it encountered. He presented the design to the Auto-Cycle Union where it was initially condemned, but later converted to the idea and made them compulsory for the 1914 Isle of Man TT races, although there was resistance from riders. Gardner took 94 of these helmets with him to the Isle of Man, and one rider who hit a gate with a glancing blow was saved by the helmet. Dr. Gardner received a letter later from the Isle of Man medical officer stating that after the T.T. they normally had "several interesting concussion cases" but that in 1914 there were none.

In May 1935, T. E. Lawrence (known as Lawrence of Arabia) had a crash on a Brough Superior SS100 on a narrow road near his cottage near Wareham. The accident occurred because a dip in the road obstructed his view of two boys on bicycles. Swerving to avoid them, Lawrence lost control and was thrown over the handlebars. He was not wearing a helmet, and suffered serious head injuries which left him in a coma; he died after six days in the hospital. One of the doctors attending him was Hugh Cairns, a neurosurgeon, who after Lawrence's death began a long study of what he saw as the unnecessary loss of life by motorcycle despatch riders through head injuries. Cairns' research led to the increased use of crash helmets by military and civilian motorcyclists and the British Army making helmets compulsory for its riders in November 1941.

In the USSR, helmets for motorcyclists became mandatory in November 1967. Protective helmets for all motorcyclists and passengers became mandatory in January 1973.

Safety effects

A 2008 systematic study showed that helmets reduce the risk of head injury by around 69% and the risk of death by around 42%.

Although it was once speculated that wearing a motorcycle helmet increased neck and spinal injuries in a crash, recent evidence has shown the opposite to be the case: helmets protect against cervical spine injury. A study that is often cited when advancing the argument that helmets might increase the incidence of neck and spinal injuries dates back to the mid-1980s and "used flawed statistical reasoning".

Basic types

There are five basic types of helmets intended for motorcycling, and others not intended for motorcycling but which are used by some riders. All of these types of helmets are secured by a chin strap, and their protective benefits are greatly reduced, if not eliminated, if the chin strap is not securely fastened so as to maintain a snug fit.

From most to least protective, as generally accepted by riders and manufacturers, the helmet types are:

Full face

A full face helmet covers the entire head, with a rear that covers the base of the skull, and a protective section over the front of the chin. Such helmets have an open cutout in a band across the eyes and nose, and often include a clear or tinted transparent plastic face shield, known as a visor, that generally swivels up and down to allow access to the face. Many full face helmets include vents to increase the airflow to the rider. The significant attraction of these helmets is their protectiveness. Some wearers dislike the increased heat, sense of isolation, lack of wind, and reduced hearing of such helmets. Full-face helmets intended for off-road or motocross use sometimes omit the face shield, but extend the visor and chin portions to increase ventilation, since riding off-road is a very strenuous activity. Studies have shown that full face helmets offer the most protection to motorcycle riders because 35% of all crashes showed major impact on the chin-bar area. Wearing a helmet with less coverage eliminates that protection — the less coverage the helmet offers, the less protection for the rider.

Off-road / motocross

The motocross and off-road helmet has clearly elongated chin and visor portions, a chin bar, and partially open face to give the rider extra protection while wearing goggles and to allow the unhindered flow of air during the physical exertion typical of this type of riding. The visor allows the rider to dip his or her head and provide further protection from flying debris during off-road riding. It also serves the obvious purpose of shielding the wearer's eyes from the sun.

Originally, off-road helmets did not include a chin bar, with riders using helmets very similar to modern open face street helmets, and using a face mask to fend off dirt and debris from the nose and mouth. Modern off-road helmets include a (typically angular, rather than round) chin bar to provide some facial impact protection in addition to protection from flying dirt and debris. When properly combined with goggles, the result provides most of the same protective features of full face street helmets.

Modular or "flip-up"

A hybrid between full face and open face helmets for street use is the modular or "flip-up" helmet, also sometimes termed "convertible" or "flip-face". When fully assembled and closed, they resemble full face helmets by bearing a chin bar for absorbing face impacts. Its chin bar may be pivoted upwards (or, in some cases, may be removed) by a special lever to allow access to most of the face, as in an open face helmet. The rider may thus eat, drink or have a conversation without unfastening the chinstrap and removing the helmet, making them popular among motor officers. It is also popular with people who use eyeglasses as it allows them to fit a helmet without removing their glasses.

Many modular helmets are designed to be worn only in the closed position for riding, as the movable chin bar is designed as a convenience feature, useful while not actively riding. The curved shape of an open chin bar and face shield section can cause increased wind drag during riding, as air will not flow around an open modular helmet in the same way as a three-quarters helmet. Since the chin bar section also protrudes further from the forehead than a three-quarters visor, riding with the helmet in the open position may pose increased risk of neck injury in a crash. Some modular helmets are dual certified as full face and open face helmet. The chin bar of those helmets offer real protection and they can be used in the "open" position while riding. An example of such a helmet would be the BMW Motorrad System 6.

As of 2008, there have not been wide scientific studies of modular helmets to assess how protective the pivoting or removable chin bars are. Observation and unofficial testing suggest that significantly greater protection exists beyond that for an open face helmet, and may be enough to pass full-face helmet standardized tests, but the extent of protection is not fully established by all standards bodies.

The DOT standard does not require chin bar testing. The Snell Memorial Foundation recently certified a flip-up helmet for the first time. ECE 22.05 allows certification of modular helmets with or without chin bar tests, distinguished by -P (protective lower face cover) and -NP (non-protective) suffixes to the certification number, and additional warning text for non-certified chin bars.

Open face or 3/4 helmet

The open face, or "three-quarters", helmet covers the ears, cheeks, and back of the head, but lacks the lower chin bar of the full face helmet. Many offer snap-on visors that may be used by the rider to reduce sunlight glare. An open face helmet provides the same rear protection as a full face helmet, but little protection to the face, even from non-crash events.

Bugs, dust, or even wind to the face and eyes can cause rider discomfort or injury. As a result, it is not uncommon (and in some U.S. states, is required by law) for riders to wear wrap-around sunglasses or goggles to supplement eye protection with these helmets. Alternatively, many open face helmets include, or can be fitted with, a face shield, which is more effective in stopping flying insects from entering the helmet.

Half helmet

The half helmet, also referred to as a "Shorty" in the United States and "Pudding Basin" or TT helmet in the UK and popular with Rockers and road racers of the 1960s in the British Isles. It has essentially the same front design as an open face helmet but without a lowered rear in the shape of a bowl. The half helmet provides the minimum coverage generally allowed by law in the U.S., and British Standards 2001:1956.

As with the open face, it is not uncommon to augment this helmet's eye protection through other means such as goggles. Because of their inferiority compared to other helmet styles, some Motorcycle Safety Foundations prohibit the use of half helmets now.

Novelty helmets

There are other types of headwear often called "beanies," "brain buckets", or "novelty helmets", a term which arose since they are uncertified and cannot legally be called motorcycle helmets in some jurisdictions. Such items are often smaller and lighter than helmets made to U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) standards, and are unsuitable for crash protection because they lack the energy-absorbing foam that protects the brain by allowing it to come to a gradual stop during an impact. A "novelty helmet" can protect the scalp against sunburn while riding and – if it stays on during a crash – might protect the scalp against abrasion, but it has no capability to protect the skull or brain from an impact. In the US, 5% of riders wore non-DOT compliant helmets in 2013, a decrease from 7% the previous year.

Color visibility

Although black helmets are popular among motorcyclists, one study determined they offer the least visibility to motorists. Riders wearing a plain white helmet rather than a black one were associated with a 24% lower risk of suffering a motorcycle accident injury or death. This study also notes "Riders wearing high visibility clothing and white helmets are likely to be more safety conscious than other riders."

Conversely, another study, the MAIDS report, did not back up the claims that helmet color makes any difference in accident frequency, and that in fact motorcycles painted white were actually over-represented in the accident sample compared to the exposure data. While recognizing how much riders need to be seen, the MAIDS report documented that riders' clothing usually fails to do so, saying that "in 65.3% of all cases, the clothing made no contribution to the conspicuity of the rider or the PTW . There were very few cases found in which the bright clothing of the PTW rider enhanced the PTW’s overall conspicuity (46 cases). There were more cases in which the use of dark clothing decreased the conspicuity of the rider and the PTW (120 cases)." The MAIDS report was unable to recommend specific items of clothing or colors to make riders better seen.

Subsequently, however, research by Wali et al. (2019) found that: “Helmet color is also one of the factors that can increase or decrease rider conspicuity (Wells et al., 2004; Gershonetal., 2012 ). Usually, dark colored helmets (such as black) can decrease rider conspicuity whereas light colored helmets can increase conspicuity at times when the level of rider conspicuity can influence injury outcomes (as observed above in our findings and in relevant literature (Wells et al., 2004 )). Our analysis shows that black colored helmets are associated with a significant increase in the injury severity score (an increase of 4.25 units – see Table 5), whereas light colored helmets (such as silver or grey) are found associated with a significant decrease in the injury severity score (a decrease of 7.56units). These findings are in agreement with those of Wells et al. (2004) and are important and intuitive as usually dark colored helmets (such as black) can decrease rider conspicuity (especially at night) thus increasing the risk of injury (Wells et al., 2004). Interestingly, our analysis shows that white colored helmets are also associated with a significant increase in the injury severity score, given a crash (see Table 3). This finding may seem apparently unintuitive as white colored helmets are usually believed to increase rider conspicuity and thus lower risk of injury. However, note that a white outfit (such as a white helmet) may increase conspicuity in a more complex and multi-colored urban environment, whereas, it can, in fact, decrease rider’s conspicuity where a background is solely a bright sky (such as on inter-urban roads) (Gershonetal., 2012 ).”

Construction

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Modern helmets are constructed from plastics. Premium price helmets are made with fiberglass reinforced with Kevlar or carbon fiber. They generally have fabric and foam interiors for both comfort and protection. Motorcycle helmets are generally designed to distort in a crash (thus expending the energy otherwise destined for the wearer's skull), so they provide little protection at the site of their first impact, but continued protection over the remainder of the helmet.

Helmets are made with an inner EPS (expanded polystyrene foam) shell and an outer shell to protect the EPS. The density and the thickness of the EPS is designed to cushion or crush on impact to help prevent head injuries. Some manufacturers even offer different densities to offer better protection. The outer shell can be made of plastics or fiber materials. Some of the plastics offer very good protection from penetration as in Lexan (bullet-resistant glass) but will not crush on impact, so the outer shell will look undamaged but the inner EPS will be crushed. Fiberglass is less expensive than Lexan but is heavy and very labor-intensive. Fiberglass or fiber shells will crush on impact offering better protection. Some manufacturers will use Kevlar or carbon fiber to help reduce the amount of fiberglass but in the process it will make the helmet lighter and offer more protection from penetration but still crushing on impact. However, using these materials can be very expensive, and manufacturers will balance factors such as protection, comfort, weight, and additional features to meet target price points.

Function

The conventional motorcycle helmet has two principal protective components: a thin, hard, outer shell typically made from polycarbonate plastic, fiberglass, or Kevlar and a soft, thick, inner liner usually made of expanded polystyrene or polypropylene "EPS" foam. The purpose of the hard outer shell is:

- to prevent penetration of the helmet by a pointed object that might otherwise puncture the skull, and

- to provide structure to the inner liner so it does not disintegrate upon abrasive contact with pavement. This is important because the foams used have very little resistance to penetration and abrasion.

The purpose of the foam liner is to crush during an impact, thereby increasing the distance and period of time over which the head stops and reducing its deceleration.

To understand the action of a helmet, it is first necessary to understand the mechanism of head injury. The common perception that a helmet's purpose is to save the rider's head from splitting open is misleading. Skull fractures are usually not life-threatening unless the fracture is depressed and impinges on the brain beneath and bone fractures usually heal over a relatively short period. Brain injuries are much more serious. They frequently result in death, permanent disability or personality change and, unlike bone, neurological tissue has very limited ability to recover after an injury. Therefore, the primary purpose of a helmet is to prevent traumatic brain injury while skull and face injuries are a significant secondary concern.

Laws and standards

Motorcycle helmets greatly reduce injuries and fatalities in motorcycle accidents, thus many countries have laws requiring acceptable helmets to be worn by motorcycle riders. These laws vary considerably, often exempting mopeds and other small-displacement bikes. In some countries, most notably the United States and India, there is opposition to compulsory helmet use (see Helmet Law Defense League); not all US states have a compulsory helmet law.

Many countries have set standards for the effectiveness of a motorcycle helmet, including the following.

Europe

European countries apply the United Nations standard ECE 22.06, and some countries apply additional standards and testing:

In the United Kingdom, many riders choose helmets bearing an Auto-Cycle Union (ACU) Gold sticker. There used to be both Gold and Silver stickers, where the Gold stickers met the BSI Type A standards and the Silver stickers met the BSI Type B. The Silver stickers are no longer in use though, as the introduction of the Economic Communities of Europe (ECE) standard provided a clearer, more stringent testing system which made the Silver standards redundant.

Helmets with an ACU Gold sticker are the only ones allowed to be worn in competition or at track days. However, Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) homologation is superseding the outdated ACU Gold in motorcycle racing. The requirements for FIM homologation are more up-to-date (2019) than the much older ACU Gold standard.

North America

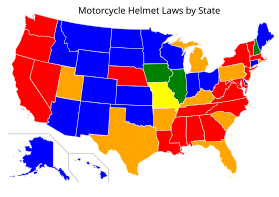

Helmets are required in Canada and Mexico. In the US, see map: helmets are required in most states of the west and east coasts as well as the southeast, while most states in the center of the country require helmets only for new or young riders, if at all.

North American standards include:

- CMVSS (Canada)

- United States Department of Transportation (DOT) FMVSS 218

- Snell M2005 & M2010 (United States)

The Snell Memorial Foundation has developed stricter requirements and testing procedures for motorcycle helmets with racing in mind, as well as helmets for other activities (such as drag racing, bicycling, horseback riding), and many riders in North America consider Snell certification a benefit when considering buying a helmet while others note that its standards allow for more force (g's) to be transferred to a rider's head than the US Department of Transportation (DOT) standard. However, the DOT standard does not test the chin bar of helmets with them, while the Snell (and ECE) standards do for full-face type only.

South America

One South American standard is NBR 7471 (Norma Brasileira by Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas, Brazil).

Asia and Oceania

Standards in Asia and Oceania include:

- AS/NZS 1698, (Australia and New Zealand)

- CRASH (Consumer Rating and Assessment of Safety Helmets, Australia)

- GB 811-2010 (China)

- ICC (Import Commodity Clearance, Philippines)

- IS 4151 (Indian Standard, Bureau of Indian Standards, India)

- JIS T 8133:2000 (Japanese Industrial Standards, Japan)

- MS 1:2011 (Previously MS 1:1996. Revised standard based on ECE 22 but with added penetration test. Department of Standards Malaysia, Malaysia)

- SNI (Standar Nasional Indonesia)

- TCVN 5756:2001 (test and certify by QUATEST 3) (Vietnam)

Worldwide: ECE 22.05

The United Nations' ECE regulation no. 22.05 contains "uniform provisions concerning the approval of protective helmets and their visors for drivers and passengers of motor cycles and mopeds". It is an addendum to the 1958 UN agreement "concerning the Adoption of Harmonized Technical United Nations Regulations for Wheeled Vehicles, Equipment and Parts". The number indicates that it is regulation no. 22, incorporating the 05 series of amendments to the standard.

As first issued in 1972, Regulation No. 22 contained requirements concerning coverage of the head, field of vision, hearing for the user, projections from the helmet, and durability of materials, as well as a series of tests regarding cold, heat and moisture treatments, shock absorption, penetration, rigidity, chinstraps and flammability. It stipulated a maximum helmet mass of 1 kg. Subsequent changes have improved the stringency of the testing procedures, among other issues.

The standard also describes how helmets must be labeled, including with such information as how to wear and clean the helmet, its size and mass, and warnings to replace the helmet after a violent impact. Helmets must also carry a type approval mark of the form "Eaa 05bbbb/c-dddd". This mark encodes the following information:

- Eaa (within a circle): The number of the country whose authorities approved the helmet (some are no longer parties to the regulation):

- E1: Germany

- E2: France

- E3: Italy

- E4: the Netherlands

- E5: Sweden

- E6: Belgium

- E7: Hungary

- E8: Czech Republic

- E9: Spain

- E10: Yugoslavia

- E11: United Kingdom

- E12: Austria

- E13: Luxembourg

- E14: Switzerland

- E16: Norway

- E17: Finland

- E18: Denmark

- E19: Romania

- E20: Poland

- E21: Portugal

- E22: Russia

- E23: Greece

- E24: Ireland

- E25: Croatia

- E26: Slovenia

- E27: Slovakia

- E28: Belarus

- E29: Estonia

- E31: Bosnia and Herzegovina

- E32: Latvia

- E34: Bulgaria

- E36: Lithuania

- E37: Turkey

- E39: Azerbaijan

- E40: Macedonia (now North Macedonia)

- E42: European Community (unused, as approvals are made by the member states)

- E43: Japan

- E45: Australia

- E46: Ukraine

- E47: South Africa

- E48: New Zealand

- 05: The series of amendments (effectively, the version number) of the standard tested (at present, normally 05)

- bbbb: The approval number issued by the approving authority

- c: The type of helmet:

- "J" if the helmet does not have a lower face cover ("jet-style helmet")

- "P" if the helmet has a protective lower face cover

- "NP" if the helmet has a non-protective lower face cover

- dddd: The continuous production serial number of the individual helmet

As of December 2017, ECE 22.05 was in force in the European Union, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Egypt, Malaysia, Montenegro, New Zealand, Moldova, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, North Macedonia and Turkey. Other countries have national standards that are based on or reference ECE 22.05.

Standards testing

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Most motorcycle helmet standards use impacts at speeds between 4–7 m/s (9–16 mph). While motorcyclists frequently ride at speeds higher than 20 m/s (45 mph), the perpendicular impact speed of the helmet is usually not the same as the road speed of the motorcycle, and the severity of the impact is determined not only by the speed of the head but also by the surface it hits and the angle of impact.

Since the surface of the road is almost parallel to the direction a motorcyclist moves while driving, only a small component of their velocity is directed perpendicularly (though other surfaces may be perpendicular to the motorcyclist's velocity, such as trees, walls, and the sides of other vehicles). The severity of an impact is also influenced by the nature of the surface struck. The sheet metal wall of a car door may bend inwards to a depth of 7.5–10 cm (3.0–3.9 in) during a helmeted-head impact, allowing more stopping distance for the rider's head than the helmet itself. A perpendicular impact against a flat steel anvil at 5 m/s (11 mph) may be of approximate severity to an oblique impact against a concrete surface at 30 m/s (67 mph) or a perpendicular impact against a sheet metal car door or windscreen at 30 m/s.

Since there is a wide range of severity in the impacts that could happen in a motorcycle accident, some will be more severe than the impacts used in the standard tests and some will be less.

See also

References

- Sung, Kang-Min; Noble, Jennifer; Kim, Sang-Chul; Jeon, Hyeok-Jin; Kim, Jin-Yong; Do, Han-Ho; Park, Sang-O; Lee, Kyeong-Ryong; Baek, Kwang-Je (2016). "The Preventive Effect of Head Injury by Helmet Type in Motorcycle Crashes: A Rural Korean Single-Center Observational Study". BioMed Research International. 2016: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2016/1849134. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 4909893. PMID 27340652.

- Vasan, S.S.; Gururaj, G. (2021). "Unhelmeted two-wheeler riders in India". The National Medical Journal of India. 34 (3): 171–172. doi:10.25259/NMJI_455_18. PMID 34825550. S2CID 240491852.

- Wang, Chenzhu; Ijaz, Muhammad; Chen, Fei; Song, Dongdong; Hou, Mingyu; Zhang, Yunlong; Cheng, Jianchuan; Zahid, Muhammad (2023-07-03). "Differences in single-vehicle motorcycle crashes caused by distraction and overspeed behaviors: considering temporal shifts and unobserved heterogeneity in prediction". International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 30 (3): 375–391. doi:10.1080/17457300.2023.2200768. ISSN 1745-7300.

- "Deformation mechanisms and energy absorption of polystyrene foams for protective helmets". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- "How the crash helmet originated", Motor Cycle magazine, June 22nd, 1922

- Paul Harvey, The Rest of the Story, KGO 810AM, August/September 2006.

- Maartens, N. F.; Wills, A. D.; Adams, C. B. (2002). "Lawrence of Arabia, Sir Hugh Cairns, and the origin of motorcycle helmets". Neurosurgery. 50 (1): 176–9, discussion 179-80. doi:10.1097/00006123-200201000-00026. PMID 11844248. S2CID 28233149.

- "Lawrence of Arabia and the crash helmet". BBC News. 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- А. Дугинов. Новый закон дороги // журнал "Наука и жизнь", № 2, 1973. стр.87-88

- Liu, B. C.; Ivers, R.; Norton, R.; Boufous, S.; Blows, S.; Lo, S. K. (2008). Liu, Bette C (ed.). "Helmets for preventing injury in motorcycle riders" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004333. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004333.pub3. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30009360. PMID 18254047.

- "Cycle Helmets May Be Killers", The Evening Independent, August 18, 1973, retrieved November 5, 2012

- Motorcycle Helmets Reduce Spine Injuries After Collisions; Helmet Weight as Risk to Neck Called a 'Myth' (press release), Johns Hopkins Medicine, February 8, 2011

- "Motorcycle Helmets Help Protect Against Spine Injury: Study; Researchers debunk myth that weight of head protection puts neck at risk in crash", U.S. News & World Report, February 15, 2011, retrieved November 5, 2012

- Dietmar Otte, Hannover Medical University, Department of Traffic Accident Research, Germany

- Kresnak, B. (2011). Motorcycling For Dummies. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-06842-7. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- "Seven Flip-Face Motorcycle Helmets Compared". Motorcycle Cruiser. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Zeus ZS3000 Review". WebBikeWorld. webWorld International. 2009.

- "Why won't Snell certify some types of helmets like flip up front designs?". FAQs about Snell and Helmets. Snell Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "ECE 22.05 Motorcycle Helmet Standard, revision 2" (PDF). Economic Commission for Europe. 16 October 1995. pp. subsection 5.1.4.1.2.1. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "ECE 22.05 Motorcycle Helmet Standard, revision 2" (PDF). Economic Commission for Europe. 16 October 1995. pp. subsection 14.1. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- Classic Motorcycling: A Guide for the 21st Century by Rex Bunn. 2007

- The BSA Gold Star by Mick Walker, 2004

- Covell, Claudia (May 14, 2007), "Counterfeit and Noncompliant Safety Equipment Motorcycle Helmets" (PDF), 2007 Government/Industry Meeting, US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- Turner, P.A. & Hagelin, C.A.. (2000). Novelty helmet use by motorcycle riders in Florida. 69-76.

- Trowbridge, Gordon (May 20, 2015), DOT takes action to address unsafe motorcycle helmets NHTSA 21-15

- Thom, David (June 2002), "Six critical facts about helmets", Motorcyclist, pp. 130+

- "Helmet use increases ... in certain conditions", Dealernews, 51 (3): 40 – via General OneFile (subscription required) , March 2015

- Susan Wells; et al. (10 April 2004). "Motorcycle rider conspicuity and crash related injury: case-control study". BMJ. 328 (7444): 857. doi:10.1136/bmj.37984.574757.EE. PMC 387473. PMID 14742349. Retrieved 2 September 2007. Abstract, Quick summary

- "Table 5.5: Predominating PTW colour". MAIDS (Motorcycle Accidents In Depth Study) Final Report 2.0. ACEM, the European Association of Motorcycle Manufacturers. April 2009. p. 47.

- "MAIDS (Motorcycle Accidents In Depth Study) Final Report 2.0". ACEM, the European Association of Motorcycle Manufacturers. April 2009. p. 100.

- Wali, B., Khattak, A.J. and Ahmad, N. (2019) ‘Examining correlations between motorcyclist’s conspicuity, apparel related factors and injury severity score: Evidence from new motorcycle crash causation study’, Accident Analysis & Prevention, 131, pp. 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2019.04.009

- Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, World Health Organization, p. Chapter 1 – Why are helmets needed?

- Kraus, Jess F.; Peek, Corinne; McArthur, David L.; Williams, Allan (1994). "The Effect of the 1992 California Motorcycle Helmet Use Law on Motorcycle Crash Fatalities and Injuries". JAMA. 272 (19): 1506–1511.

- "Motorcycles: Motorcycle helmet laws by state". iihs.org. IIHS-HLDI crash testing and highway safety. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- "Canadian Motorcycle Helmet Requirements". motorcyclelicense.ca.

- "Manejar motocicletas con seguridad". gob.mx (in Spanish).

- "Standard No. 218; Motorcycle helmets" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations, Title 49, section 571.218. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 1 October 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ "CAP 374F ROAD TRAFFIC (SAFETY EQUIPMENT) REGULATIONS Schedule 1 APPROVED PROTECTIVE HELMETS". hklii.hk.

- Ford, Dexter (June 2005). "Motorcycle Helmet Performance: Blowing the Lid Off". Motorcyclist. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- "Standard No. 218; Motorcycle helmets" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations, Title 49, section 571.218. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 1 October 2007. pp. subsection S6.2.3. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Welcome to CRASH!". crash.org.au. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Regulation No. 22. Uniform provisions concerning the approval of protective helmets and their visors for drivers and passengers of motor cycles and mopeds, E/ECE/TRANS/505, Rev.1/Add.21/Rev.4" (PDF). UNECE. 24 September 2002. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "The United Nations Motorcycle Helmet Study, ECE/TRANS/252" (PDF). unece.org. United Nations. 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ECE 22.05 para. 5.1

- "Regulation No. 22. Uniform provisions concerning the approval of protective helmets and their visors for drivers and passengers of motor cycles and mopeds". un.org. United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

External links

| Helmets | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual historical helmets |

| ||||||||||||||

| Combat |

| ||||||||||||||

| Athletic | |||||||||||||||

| Work | |||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||

| Motorcycles and motorcycling (outline) | |

|---|---|

| General topics | |

| Types |

|

| Design | |

| Manufacturers | |

| Media | |

| Touring | |

| Equipment | |

| Sport | |

| Organizations | |