Multipole magnets are magnets built from multiple individual magnets, typically used to control beams of charged particles. Each type of magnet serves a particular purpose.

- Dipole magnets are used to bend the trajectory of particles

- Quadrupole magnets are used to focus particle beams

- Sextupole magnets are used to correct for chromaticity introduced by quadrupole magnets

Magnetic field equations

The magnetic field of an ideal multipole magnet in an accelerator is typically modeled as having no (or a constant) component parallel to the nominal beam direction ( direction) and the transverse components can be written as complex numbers:

where and are the coordinates in the plane transverse to the nominal beam direction. is a complex number specifying the orientation and strength of the magnetic field. and are the components of the magnetic field in the corresponding directions. Fields with a real are called 'normal' while fields with purely imaginary are called 'skewed'.

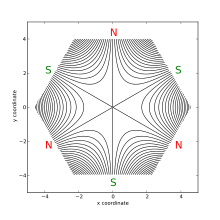

| n | name | magnetic field lines | example device |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dipole |  |

|

| 2 | quadrupole |  |

|

| 3 | sextupole |  |

|

Stored energy equation

Main article: Magnetic energyFor an electromagnet with a cylindrical bore, producing a pure multipole field of order , the stored magnetic energy is:

Here, is the permeability of free space, is the effective length of the magnet (the length of the magnet, including the fringing fields), is the number of turns in one of the coils (such that the entire device has turns), and is the current flowing in the coils. Formulating the energy in terms of can be useful, since the magnitude of the field and the bore radius do not need to be measured.

Note that for a non-electromagnet, this equation still holds if the magnetic excitation can be expressed in Amperes.

Derivation

The equation for stored energy in an arbitrary magnetic field is:

Here, is the permeability of free space, is the magnitude of the field, and is an infinitesimal element of volume. Now for an electromagnet with a cylindrical bore of radius , producing a pure multipole field of order , this integral becomes:

Ampere's Law for multipole electromagnets gives the field within the bore as:

Here, is the radial coordinate. It can be seen that along the field of a dipole is constant, the field of a quadrupole magnet is linearly increasing (i.e. has a constant gradient), and the field of a sextupole magnet is parabolically increasing (i.e. has a constant second derivative). Substituting this equation into the previous equation for gives:

References

- "Varna 2010 | the CERN Accelerator School" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-13.

- "Wolski, Maxwell's Equations for Magnets – CERN Accelerator School 2009".

- Griffiths, David (2013). Introduction to Electromagnetism (4th ed.). Illinois: Pearson. p. 329.

- Tanabe, Jack (2005). Iron Dominated Electromagnets - Design, Fabrication, Assembly and Measurements (4th ed.). Singapore: World Scientific.

direction)

and the transverse components can be written as complex numbers:

direction)

and the transverse components can be written as complex numbers:

and

and  are the coordinates in the plane transverse to the nominal beam direction.

are the coordinates in the plane transverse to the nominal beam direction.  is a complex number specifying the orientation and strength of the magnetic field.

is a complex number specifying the orientation and strength of the magnetic field.  and

and  are the components of the magnetic field in the corresponding directions. Fields with a real

are the components of the magnetic field in the corresponding directions. Fields with a real  , the stored magnetic energy is:

, the stored magnetic energy is:

is the permeability of free space,

is the permeability of free space,  is the effective length of the magnet (the length of the magnet, including the fringing fields),

is the effective length of the magnet (the length of the magnet, including the fringing fields),  is the number of turns in one of the coils (such that the entire device has

is the number of turns in one of the coils (such that the entire device has  turns), and

turns), and  is the current flowing in the coils. Formulating the energy in terms of

is the current flowing in the coils. Formulating the energy in terms of  can be useful, since the magnitude of the field and the bore radius do not need to be measured.

can be useful, since the magnitude of the field and the bore radius do not need to be measured.

is the magnitude of the field, and

is the magnitude of the field, and  is an infinitesimal element of volume. Now for an electromagnet with a cylindrical bore of radius

is an infinitesimal element of volume. Now for an electromagnet with a cylindrical bore of radius  , producing a pure multipole field of order

, producing a pure multipole field of order

is the radial coordinate. It can be seen that along

is the radial coordinate. It can be seen that along  gives:

gives: