| Gelibolulu Mustafa Ali | |

|---|---|

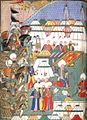

Lala Mustafa Pasha, illustration from Mustafa Ali's book, Nusretnāme (Book of Victory), 1580 Lala Mustafa Pasha, illustration from Mustafa Ali's book, Nusretnāme (Book of Victory), 1580 | |

| Born | (1541-04-28)April 28, 1541 Gelibolu, Ottoman Empire (now Gallipoli, Turkey) |

| Died | 1600 (aged 58–59) Jeddah, Arabia (now in Saudi Arabia) |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Occupation(s) | Historian, Bureaucrat, Poet |

| Notable work | Künhü'l-aḫbār, Nusretnāme, Mihr ü Mâh |

Gelibolulu Mustafa Âlî bin Ahmed bin Abdülmevlâ Çelebi (lit. "Mustafa Ali of Gallipoli son of Ahmed son of Abdülmevla the Godly"; 28 April 1541 – 1600) was an Ottoman historian, bureaucrat and major literary figure.

Life and work

Mustafa Ali was born on 28 April 1541 in Gelibolu, a provincial town on the Dardanelles. His father, Ahmad, son of Mawla, was a learned man and a prosperous local merchant. The family was well-connected. Ali's uncle was Dervish Chalabi, imam to the Sultan Suleyman. The family was possibly of Bosnian ancestry.

He began his formal education at age 6 and was trained in religion and logic. At the age of 15, he began to write poetry and initially wrote under the pen-name Chasmi (The Hopeful), but before long took up the name of Âlî (The Exalted). He continued his education in Istanbul where he studied holy law, lettering and grammar. He gained employment as a cleric at the Chancery, after writing a poem, Mihr ü Mâh (The Sun and the Moon), designed to impress Prince Salim. He later entered the Court of the Sultan Suleyman, but his ambition displeased the court members and he was sent back to the Prince's Court.

While working at the Prince's Court, he accepted an offer to serve as the confidential secretary to Lala Mustafa Pasha, a former mentor to the Prince. For the next twenty years, his life paralleled that of his employer, who by that time was a Grand Vizier. Ali's duties took him various parts of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East including Aleppo, Damascus and Egypt.

When Prince Selim succeeded his father to the throne, Pasha and Ali entered the Royal Court in Istanbul. He used the opportunity to enter literary society and mingle with prominent literary figures of the day. However, that interlude was short-lived. Ali was assigned military duties and spent seven years in Bosnia, after which he served various administrative roles in provincial towns as far away as Baghdad and Dalmatia. He felt that these military and administrative posts were unsuited to him, as a man of letters and a man of the pen. He regularly appealed to the Court for better assignments and desperately tried to find a way back to Istanbul, to no avail. His constant frustrations and resentment, however, stimulated an active period of literary output. Many of his best works were written during this period. During his time in Baghdad, he used the opportunity to carry out research for his grand history, later published as Künhü'l-aḫbār (The Essence of History).

He became a major literary figure in the second half of the sixteenth century, and had a prolific output. He is most famous for his immense work of world history, entitled Künhü'l-aḫbār, covering the period from the creation of the world to the year 1000 of the Islamic calendar (1591/92 AD). This work remains an important primary source for 16th-century Ottoman history. He also wrote poetry as well as a work of nasihatname literature entitled Nuṣḥatü's-selāṭīn (Counsel for Sultans).

In July, 1599 he travelled to Cairo before taking up what would be his last appointment as Governor of Jeddah. He spent five months in Egypt, where he wrote a book on the customs and traditions of Cairo. He became ill in Jeddah and died there at the age of 58.

Selected writings

Ali wrote some 55 works. Ali not only composed and penned his works, he also provided some of the illustrations. At the time, the illustration of historical works was a new trend.

- Nuṣḥatü's-selāṭīn (Counsel for Sultans), 1581

- Nusretnāme (Book of Victory), 1580 - an illustrated history of the Shirvan campaign

- Cāmi'i'l-Buhür der Mecalis-i-Sür (Gathering of the Seas), 1583

- Menlāab-i Hüner-Verān (Epic Deeds of Artists and Calligraphers), 1586

- Ferā'i'dü'l-Vilāde (Unique Pearls of Birth), 1587

- Künhü'l-aḫbār (The Essence of History), 1587

- Mir'atü-avālim (Mirror of Worlds), c. 1587

- Sadef-i Sad Guher (Lustre of One Hundred Jewells), 1593

- Mevadü’n-nefa'is fı qavā'idi’l Mecālı's (Table of Delicacies Concerning the Rules of Social Gatherings), 1599 - a work detailing etiquette in Cairo

Selected Illustrations from Mustafa Âlî's book, Nusretnāme

-

The Army's departure from the palace

The Army's departure from the palace

-

Lala Mustafa Pasha in camp after his victory

Lala Mustafa Pasha in camp after his victory

-

Banquet given by Lala Mustafa Pasha to the Jannissaries

Banquet given by Lala Mustafa Pasha to the Jannissaries

-

Ottoman army at Tiflis in 1578

Ottoman army at Tiflis in 1578

See also

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Islamic art

- Islamic calligraphy

- List of Ottoman calligraphers

- Ottoman art

References

- ^ Fleischer 1986, p. 16.

- Akın 2011, pp. 18–19.

- Akın 2011, pp. 20–23.

- Fleischer 1986, pp. 7–8.

- Akın 2011, pp. 27.

- Akın 2011, p. 24.

Bibliography

- Fleischer, Cornell (1986). Bureaucrat and Intellectual in the Ottoman Empire: The Historian Mustafa Âli, 1541-1600. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-59740-462-4.

- Akın, Esra (2011). Mustafa Âli's Epic Deeds of Artists: A Critical Edition of the Earliest Ottoman Text about the Calligraphers and Painters of the Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 9789047441076.

External links

- Les calligraphes et les miniaturistes de l'Orient musulman by Huart, Clément – digital copy of a work that draws on Mustafa Âlî's Epic Deeds of Calligraphers and Artists