| This article provides insufficient context for those unfamiliar with the subject. Please help improve the article by providing more context for the reader. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

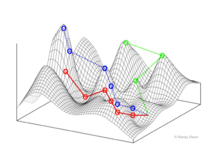

The NK model is a mathematical model described by its primary inventor Stuart Kauffman as a "tunably rugged" fitness landscape. "Tunable ruggedness" captures the intuition that both the overall size of the landscape and the number of its local "hills and valleys" can be adjusted via changes to its two parameters, and , with being the length of a string of evolution and determining the level of landscape ruggedness.

The NK model has found application in a wide variety of fields, including the theoretical study of evolutionary biology, immunology, optimisation, technological evolution, team science, and complex systems. The model was also adopted in organizational theory, where it is used to describe the way an agent may search a landscape by manipulating various characteristics of itself. For example, an agent can be an organization, the hills and valleys represent profit (or changes thereof), and movement on the landscape necessitates organizational decisions (such as adding product lines or altering the organizational structure), which tend to interact with each other and affect profit in a complex fashion.

An early version of the model, which considered only the smoothest () and most rugged () landscapes, was presented in Kauffman and Levin (1987). The model as it is currently known first appeared in Kauffman and Weinberger (1989).

One of the reasons why the model has attracted wide attention in optimisation is that it is a particularly simple instance of a so-called NP-complete problem which means it is difficult to find global optima. Recently, it was shown that the NK model for K > 1 is also PLS-complete which means than, in general, it is difficult to find even local fitness optima. This has consequences for the study of open-ended evolution.

Prototypical example: plasmid fitness

A plasmid is a small circle of DNA inside certain cells that can replicate independently of their host cells. Suppose we wish to study the fitness of plasmids.

For simplicity, we model a plasmid as a ring of N possible genes, always in the same order, and each can have two possible states (active or inactive, type X or type Y, etc...). Then the plasmid is modelled by a binary string with length N, and so the fitness function is .

The simplest model would have the genes not interacting with each other, and so we obtainwhere each denotes the contribution to fitness of gene at location .

To model epistasis, we introduce another factor K, the number of other genes that a gene interacts with. It is reasonable to assume that on a plasmid, two genes interact if they are adjacent, thus givingFor example, when K = 1, and N = 5,

The NK model generalizes this by allowing arbitrary finite K, N, as well as allowing arbitrary definition of adjacency of genes (the genes do not necessarily lie on a circle or a line segment).

Mathematical definition

The NK model defines a combinatorial phase space, consisting of every string (chosen from a given alphabet) of length . For each string in this search space, a scalar value (called the fitness) is defined. If a distance metric is defined between strings, the resulting structure is a landscape.

Fitness values are defined according to the specific incarnation of the model, but the key feature of the NK model is that the fitness of a given string is the sum of contributions from each locus in the string:

and the contribution from each locus in general depends on its state and the state of other loci,:

where is the index of the th neighbor of locus .

Hence, the fitness function is a mapping between strings of length K + 1 and scalars, which Weinberger's later work calls "fitness contributions". Such fitness contributions are often chosen randomly from some specified probability distribution.

Example: the spin glass models

The 1D Ising model of spin glass is usually written aswhere is the Hamiltonian, which can be thought as energy.

We can reformulate it as a special case of the NK model with K=1:by definingIn general, the m-dimensional Ising model on a square grid is an NK model with .

Since K roughly measures "ruggedness" of the fitness landscape (see below), we see that as the dimension of Ising model increases, its ruggedness also increases.

When , this is the Edwards–Anderson model, which is exactly solvable.

The Sherrington–Kirkpatrick model generalizes the Ising model by allowing all possible pairs of spins to interact (instead of a grid graph, use the complete graph), thus it is also an NK model with .

Allowing all possible subsequences of spins to interact, instead of merely pairs, we obtain the infinite-range model, which is also an NK model with .

Tunable topology

The value of K controls the degree of epistasis in the NK model, or how much other loci affect the fitness contribution of a given locus. With K = 0, the fitness of a given string is a simple sum of individual contributions of loci: for nontrivial fitness functions, a global optimum is present and easy to locate (the genome of all 0s if f(0) > f(1), or all 1s if f(1) > f(0)). For nonzero K, the fitness of a string is a sum of fitnesses of substrings, which may interact to frustrate the system (consider how to achieve optimal fitness in the example above). Increasing K thus increases the ruggedness of the fitness landscape.

Variations with neutral spaces

The bare NK model does not support the phenomenon of neutral space -- that is, sets of genomes connected by single mutations that have the same fitness value. Two adaptations have been proposed to include this biologically important structure. The NKP model introduces a parameter : a proportion of the fitness contributions is set to zero, so that the contributions of several genetic motifs are degenerate . The NKQ model introduces a parameter and enforces a discretisation on the possible fitness contribution values so that each contribution takes one of possible values, again introducing degeneracy in the contributions from some genetic motifs . The bare NK model corresponds to the and cases under these parameterisations.

Known results

In 1991, Weinberger published a detailed analysis of the case in which and the fitness contributions are chosen randomly. His analytical estimate of the number of local optima was later shown to be flawed . However, numerical experiments included in Weinberger's analysis support his analytical result that the expected fitness of a string is normally distributed with a mean of approximately

and a variance of approximately

.

Applications

The NK model has found use in many fields, including in the study of spin glasses, collective problem solving, epistasis and pleiotropy in evolutionary biology, and combinatorial optimisation.

References

- Boroomand, Amin; Smaldino, Paul E. (2023). "Superiority bias and communication noise can enhance collective problem solving". Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 26 (3). doi:10.18564/jasss.5154.

- Levinthal, D. A. (1997). "Adaptation on Rugged Landscapes". Management Science. 43 (7): 934–950. doi:10.1287/mnsc.43.7.934.

- Kauffman, S.; Levin, S. (1987). "Towards a general theory of adaptive walks on rugged landscapes". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 128 (1): 11–45. Bibcode:1987JThBi.128...11K. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(87)80029-2. PMID 3431131.

- Kauffman, S.; Weinberger, E. (1989). "The NK Model of rugged fitness landscapes and its application to the maturation of the immune response". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 141 (2): 211–245. Bibcode:1989JThBi.141..211K. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(89)80019-0. PMID 2632988.

- Weinberger, E. (1996), "NP-completeness of Kauffman's N-k model, a Tuneably Rugged Fitness Landscape", Santa Fe Institute Working Paper, 96-02-003.

- Kaznatcheev, Artem (2019). "Computational Complexity as an Ultimate Constraint on Evolution". Genetics. 212 (1): 245–265. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302000. PMC 6499524. PMID 30833289.

- Weinberger, Edward (November 15, 1991). "Local properties of Kauffman's N-k model: A tunably rugged energy landscape". Physical Review A. 10. 44 (10): 6399–6413. Bibcode:1991PhRvA..44.6399W. doi:10.1103/physreva.44.6399. PMID 9905770.

- Boroomand, A. and Smaldino, P.E., 2021. Hard Work, Risk-Taking, and Diversity in a Model of Collective Problem Solving. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(4).

and

and  , with

, with  ) and most rugged (

) and most rugged ( ) landscapes, was presented in Kauffman and Levin (1987). The model as it is currently known first appeared in Kauffman and Weinberger (1989).

) landscapes, was presented in Kauffman and Levin (1987). The model as it is currently known first appeared in Kauffman and Weinberger (1989).

.

.

where each

where each  denotes the contribution to fitness of gene

denotes the contribution to fitness of gene  at location

at location  .

.

For example, when K = 1, and N = 5,

For example, when K = 1, and N = 5,

is the sum of contributions from each locus

is the sum of contributions from each locus  in the string:

in the string:

is the index of the

is the index of the  th neighbor of locus

th neighbor of locus  is a

is a  where

where  is the Hamiltonian, which can be thought as energy.

is the Hamiltonian, which can be thought as energy.

by defining

by defining In general, the m-dimensional Ising model on a square grid

In general, the m-dimensional Ising model on a square grid  is an NK model with

is an NK model with  .

.

, this is the Edwards–Anderson model, which is exactly solvable.

, this is the Edwards–Anderson model, which is exactly solvable.

: a proportion

: a proportion  fitness contributions is set to zero, so that the contributions of several genetic motifs are degenerate . The NKQ model introduces a parameter

fitness contributions is set to zero, so that the contributions of several genetic motifs are degenerate . The NKQ model introduces a parameter  and enforces a discretisation on the possible fitness contribution values so that each contribution takes one of

and enforces a discretisation on the possible fitness contribution values so that each contribution takes one of  and

and  cases under these parameterisations.

cases under these parameterisations.

and the fitness contributions are chosen randomly. His analytical estimate of the number of local optima was later shown to be flawed . However, numerical experiments included in Weinberger's analysis support his analytical result that the expected fitness of a string is normally distributed with a mean of approximately

and the fitness contributions are chosen randomly. His analytical estimate of the number of local optima was later shown to be flawed . However, numerical experiments included in Weinberger's analysis support his analytical result that the expected fitness of a string is normally distributed with a mean of approximately

.

.