The pinas Naga Pelangi in Langkawi, 2010 The pinas Naga Pelangi in Langkawi, 2010

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Naga Pelangi |

| Port of registry | Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg |

| Ordered | 2003 |

| Builder | Traditional Malay |

| Laid down | 2004 |

| Launched | 2009 |

| Status | Charter vessel |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Traditional Malay junk schooner |

| Displacement | 70 tonnes (77 short tons) |

| Length | 22 m (72 ft 2 in) LOD |

| Beam | 6 m (19 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 3 m (9 ft 10 in) |

| Propulsion | Sail; auxiliary engine |

| Sail plan | Junk schooner, 300 square metres (3,200 sq ft) total sail area |

| Capacity | 8 persons (not including crew) |

| Crew | 4 |

| |

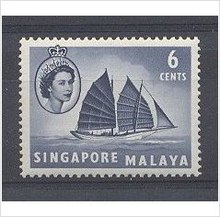

Naga Pelangi (Rainbow Dragon) is a wooden junk rigged schooner of the Malay pinas type built using traditional lashed-lug techniques from 2004 to 2009 in Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia. Finished in 2010, it is operated as a charter vessel in South East Asia.

Background

The Naga Pelangi was built for Christoph Swoboda from Germany by the craftsmen of Duyong Island in the estuary of the Terengganu River in the state of Terengganu on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. It is a Malay-style sailing boat with lines based on the traditional pinas-design but finished to modern yacht standards.

In Malaysia, these sailing boats are called Perahu Besar, (Malay: big boat). They were built for cargo and piracy and are made in two types, the bedar and the pinas. They are made of chengal wood (Neobalanocarpus heimii), a heavy hardwood of the family Dipterocarpaceae growing only on the Malay peninsula, the home of the world's oldest rainforest. These picturesque junk rigged boats have been used in the South China Sea for centuries and the last few were still in operation as sailing freighters in the 1980s.

Swoboda had a bedar built by the same craftsmen in 1981, finished a circumnavigation with that boat (the original Naga Pelangi) in 1998 and after selling it, he ordered a new vessel to be built – the pinas Naga Pelangi – in order to help keep this ancient boat building tradition alive.

The Malays have developed an indigenous technique to build wooden boats. They build without plans, hull first, frames later. The planks are fire bent and joined edge on edge using basok (wooden dowels) made from Penaga-ironwood (Mesua ferrea). There is no European style caulking hammered into a groove between the planks: Before the new plank is hammered home, a strip of paperbarks skin (Malay: kulit gelam) of the Melaleuca species is placed over the dowels. This 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) layer of a natural material has sealing properties. It is an ancient and unique building technique, the origins of which might date back to the Proto-Malay migrations that colonised the archipelago thousands of years ago.

As of 2013, Naga Pelangi is operated by its owner in the eastern Indian Ocean, the Andaman Sea with a base in Langkawi island and in the South China Sea with a base in Kuala Terengganu.

Name – Etymology

In modern Malay, Naga Pelangi, translated literally, means "Rainbow Dragon". Nāga is a Sanskrit word and means snake or dragon.

All over South East Asia, in Burmese, Thai, Vietnamese, Khmer culture, Nagas are found in various form, half snake, half dragon. For the pre-Islamic Malays the Naga was a deity living in the sea and was held in great esteem by the seafarers. Sacrifices were offered to ask for an auspicious journey and frequently the bow of their craft was adorned with a figurehead of a carved Naga. This detailed carving was reduced to a stylised carving in later times due to the strict picture ban of the Islam. The figurehead of a Malay pinas is called gobel, with the elements of the old Naga shining through.

History

The tradition of building wooden boats in modern Malaysia goes back centuries: For overseas trade, for fishing, for travelling up the many rivers, for each purpose a special design was developed. When Malacca became the main trading centre for spices arriving from the Maluku Islands, Indonesia, the Malay peninsula turned into a melting pot of the seafaring, trading civilisations: Indians and Chinese, Arabs and Indonesians, Vietnamese and Thai, Burmese, Europeans and others, all arrived in their distinctive craft, inspiring Malaysian shipbuilding.

One of the stories told is that on the eastern shore of an island in the Terengganu river mouth once sat a mermaid, an indo-pacific sea cow (Dugong dugon). Thus the island was named Pulau Duyong (Malay: pulau =island). According to legend, an historic Sultan of Terengganu encouraged the Bugis, a seafaring people from Celebes (Sulawesi, Indonesia), to settle on the island and establish a trade post. He meant to encourage trade on the east coast of the peninsula, as the Bugis were well known throughout South East Asia as traders, boat builders and pirates. They settled and stayed and it was there that boatbuilding in Malaya developed. During the times of Cheng Ho, a noted Chinese seafarer and explorer, the Terengganu boatbuilders were already known for their craft. A temple built in honour of Ho is situated up the Terengganu river in memory of his visit to this place.

In the 19th century, a French captain is said to have marvelled at the sight of a flotilla of trading vessels assembled from all corners of the globe in the harbour off Duyong island: Arab dhows, Indonesian perahus, Portuguese lorchas, English schooners, and Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai junks. The two perahu besar of Terengganu, the pinas and the bedar are the result of this cultural interchange. Pinas carry traces of French influence from French pinasse, while the bedar shows Arab/Indian (dhow) elements. Jib and bowsprit in the two are of western origin, as junks almost never carry these features. The sails of both of types are that of a classic Chinese junk: The rigging has an elaborate sheet system, parrels, snotter and lazy jack system. All have been documented in Chinese literature for over 2000 years. The desire for ever faster and more manoeuvrable vessels combined these positive elements and created these junk hybrids.

The boatbuilders of Terengganu were re-discovered during the World War II by the Japanese navy, who had wooden minesweepers built there by the carpenters and fishing folks. After the war, the Malays stopped building sailing boats for their own use, but they kept manufacturing fishing trawlers and ferries, using the old techniques. Rising timber prices and lack of demand forced one yard after another out of business, so today this tradition is on the brink of extinction, with very few craftsmen still practicing the old building technique.

Gallery

-

Naga Pelangi sailing butterfly

-

Birds-eye view from one of the masts

Birds-eye view from one of the masts

-

On the hard in Satun Thailand 2011

-

Cockpit with companionway

Cockpit with companionway

-

Deck layout

-

Fitting the first plank

Fitting the first plank

-

Building the Naga Pelangi, 2004 – frames are adjusted to hull

Building the Naga Pelangi, 2004 – frames are adjusted to hull

See also

- Bedar (ship)

- Chengal

- Junk (ship)

- Junk rig

- Junk Keying

- List of schooners

- Lorcha (boat)

- Tongkang

- Lashed-lug boat

External links

- Naga Pelangi, the Rainbow Dragon Charter Cruises

- Junk Rig Association

- Brian Platt's "The Chinese Sail"

- The Voyage of the Dragon King, Details of the junk rig, incl. diagrams and photos

- Magazine "Professional Skipper" article about the boatbuilding in Duyong

- Article published in "50 Years Malaysian-German Relations", Embassy of Germany in Kuala Lumpur

- Chengal wood

References

- Duyong Dawn of a new ara, Dato' Wan Hisham Wan Salleh, Wan Ramli Wan Muhammad, 2006, p1/96ff

- "Google Translate".

- Duyong Dawn of a new ara, Dato' Wan Hisham Wan Salleh, Wan Ramli Wan Muhammad, 2006, p94

- ^ Duyong Dawn of a new ara, Dato' Wan Hisham Wan Salleh, Wan Ramli Wan Muhammad, 2006, p95

- 100 Malaysian Timbers, published by Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986, p16/17

- 50 Years Malaysian-German Relations, Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany, p132/133

- "Google Translate".

- ^ Cargo Boats of the East Coast of Malaya, Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1949), JMBRAS 22(3), p106-125

- "Google Translate".

- Boats, Boatbuilding and Fishing in Malaysia, The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, p340

- ^ Keeping the Tradition of Boatbuilding Alive, Keith Ingram, Magazine: Professional Skipper March/April 2007, p70

- "Google Translate".

- Cargo Boats of the East Coast of Malaya, Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1949), JMBRAS 22(3), p108-110

- Boats, Boatbuilding and Fishing in Malaysia, The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society,, MBRAS 2009, p342