| Narcís Monturiol | |

|---|---|

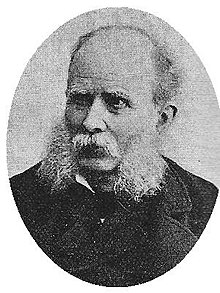

Monturiol circa 1880 Monturiol circa 1880 | |

| Born | Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol (1819-09-28)28 September 1819 Figueres, Spain |

| Died | 6 September 1885(1885-09-06) (aged 65) Sant Martí de Provençals (currently Barcelona) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation(s) | Inventor, engineer, artist, politician |

| Known for | Submarine pioneer; inventor of the Ictíneo I and Ictíneo II |

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol (Catalan pronunciation: [nəɾˈsiz muntuɾiˈɔl i əstəriˈɔl]; 28 September 1819 – 6 September 1885) was a Spanish inventor, artist and engineer born in Figueres, Spain. He was the inventor of the first air-independent and combustion-engine-driven submarine.

Biography

Monturiol i Estarriol was born in the city of Figueres, Spain. He was the son of a cooper. Monturiol went to high school in Cervera and got a law degree in Mostoles in 1845. He solved the fundamental problems of underwater navigation. In effect, Monturiol invented the first fully functional engine-driven submarine.

Monturiol never practiced law, instead turning his talents to writing and publishing, setting up a publishing company in 1846, the same year he married his wife Emilia. He produced a series of journals and pamphlets espousing his radical beliefs in feminism, pacifism, and utopian communism. He also founded the newspaper "La Madre de Familia", in which he promised "to defend women from the tyranny of men" and La Fraternidad, Spain's first communist newspaper.

Monturiol's friendship with Abdó Terrades led him to join the Republican Party and his circle of friends included such names as musician Josep Anselm Clavé, and engineer and reformist Ildefons Cerdà. Monturiol also became an enthusiastic follower of the utopian thinker and socialist Étienne Cabet; he popularised Cabet's ideas through La Fraternidad and produced a Spanish translation of his novel Voyage en Icarie. A circle formed round La Fraternidad raised enough money for one of them to travel to Cabet's utopian community, Icaria.

Following the revolutions of 1848, one of his publications was suppressed by the government and he was forced into a brief exile in France. When he returned to Barcelona in 1849, the government curtailed his publishing activities, and he turned his attention to science and engineering instead.

A stay in Cadaqués allowed him to observe the dangerous job of coral harvesters where he even witnessed the death of a man who drowned while performing this job. This prompted him to think of submarine navigation and in September 1857 he went back to Barcelona and organized the first commercial society in Spain dedicated to the exploration of submarine navigation with the name of Monturiol, Font, Altadill y Cia. and a capital of 10,000 pesetas.

In 1858 Monturiol presented his project in a scientific thesis, titled The Ictineo (Fish-Ship). The first dive of his first submarine, Ictineo I, took place in September 1859 in the harbour of Barcelona.

Ictíneo I

Main article: Ictíneo IIctíneo I was 7 m (23 ft) long with a beam of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) and draft of 3.5 m (11 ft). Her intended use was to ease the harvest of coral. Ictíneo I's prow was equipped with a set of tools suited to the harvest of coral. During the summer of 1859, Monturiol performed more than 20 dives in Ictíneo I, with his business partner and shipbuilder as crew. Ictíneo I possessed good handling, but her top speed was disappointing, as it was limited by the power of human muscles.

Ictíneo I was eventually destroyed by accident in January 1862, after completing some fifty dives, when a cargo vessel ran into her at her berth.

A modern replica of Ictíneo I stands in the garden entrance to the Marine Museum in Barcelona.

Ictíneo II

Main article: Ictíneo IIThe Ictíneo II was originally intended as an improved version of the handpowered Ictíneo I. The Spanish Navy pledged support to Monturiol but did not actually supply it, so he had to raise funds himself, writing a letter to the nation to encourage a popular subscription which raised 300,000 pesetas from the people of Spain and Cuba and was used to form the company La Navegación Submarina to develop the Ictíneo II.

Monturiol's ultimate plan envisaged a vessel custom-built to house his new engine, which would be entirely built of metal and with the engine housed in its own separate compartment. Due to the state of his finances, construction of the metal vessel was out of the question. Instead, he managed to assemble enough funds to fit the engine into the wooden Ictíneo II for preliminary tests and demonstrations.

On 22 October 1867, Ictíneo II made her first surface journey under steam power, averaging 3.5 kn (4.0 mph; 6.5 km/h) with a top speed of 4.5 kn (5.2 mph; 8.3 km/h). On 14 December, Monturiol submerged the vessel and successfully tested his air-independent engine, without attempting to travel anywhere.

On 23 December that same year, Monturiol's company went bankrupt and could attract no more investment. The chief creditor called in his debt, and Monturiol was forced to surrender his sole asset, Ictíneo II. The creditor subsequently sold her to a businessman, and the authorities, who taxed all ships, issued its new owner with a tax bill. Rather than pay the bill, he dismantled the submarine and sold it for scrap. A replica can be seen at the harbor of Barcelona.

Later life and legacy

Later life

In 1868 Monturiol returned to political life. A member of the Partido Federal, he was a deputy in the Constituent Assembly of the First Spanish Republic (1873), and shortly afterwards became the director of Fabrica Nacional del Timbre (National Stamp Factory) in Madrid for a few months, where he implemented a process to speed up the manufacturing of adhesive paper. Monturiol's other inventions included a system for copying letters, a continuous printer, a rapid-firing cannon, a system to enhance the performance of steam generators, a stone cutter, a method for preserving meat, and a machine for making cigarettes.

Monturiol died in 1885, in Sant Martí de Provençals, now a suburb of Barcelona.

Legacy

No other submarine employed an anaerobic propulsion system until 1940 when the German Navy tested a system employing the same principles, the Walter turbine, on the experimental V-80 submarine and later on the Type XVII submarines. The problem of air-independent propulsion was finally resolved with the construction of the first nuclear powered submarine, the USS Nautilus.

Spain honored Monturiol on a postage stamp in 1987 (purportedly his death centennial; the reason for the discrepancy is unclear).

He has two monuments: one in Barcelona (Avinguda Diagonal-Carrer Girona) and other at the end of the Rambla in Figueres, his native city, better known for another Figuerenc, Salvador Dalí.

The Spanish Navy has honored his name giving it to what will be the first launched submarine of air independent propulsion in active service in the Spanish Navy, the S-82 Narciso Monturiol (the S-81 Isaac Peral being launched the last due to construction issues).

In 2013 a crewed submersible capable of reaching depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft) was named Ictineu 3 honouring Monturiol's inventions, Ictineo I and Ictineo II.

Notes

- Cargill Hall, R. (1986). History of rocketry and astronautics: proceedings of the third through the sixth History Symposia of the International Academy of Astronautics, Volumen 1. NASA conference publication. American Astronautical Society by Univelt, p. 85. ISBN 0-87703-260-2

- A steam powered submarine: the Ictíneo Archived 21 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine Low-tech Magazine, 24 August 2008

- Stewart, Matthew (2003). Monturiol's Dream: The Extraordinary Story of the Submarine Inventor Who Wanted to Save the World. Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 1-86197-470-1.

- Cindy Lee Van Dover. A Utopian's Submarine Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2008-08-01

- "Monturiol Estarriol, Narciso". Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas. Archived from the original on 23 December 2009.

- "Timbre 1516966: Narciso Monturiol". Le Marché du Timbre.

- Alcocer, Alex; Forès, Pere; Giuffré, Gian Piero; Parareda, Carme. "The Ictineu 3 project: a modern manned submersible for scientific research and intervention" (PDF). upcommons.upc.edu. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

References

- Stewart, Matthew (2003). Monturiol's Dream: The Extraordinary Story of the Submarine Inventor Who Wanted to Save the World. Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 1-86197-470-1.

- Editorial Ramón Sopena; Diccionario Enciclopédico Ilustrado 1962

- https://archive.org/details/ELFRACASODENARCISOMONTURIOL

External links

- Monturiol, a forgotten submariner; by Thomas Holian in Undersea Warfare

- critic on Monturiols dream written by Matthew Stewart