A seal is a device for making an impression in wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or to prevent interference with a package or envelope by applying a seal which had to be broken to open the container (hence the modern English verb "to seal", which implies secure closing without an actual wax seal).

The seal-making device is also referred to as the seal matrix or die; the imprint it creates as the seal impression (or, more rarely, the sealing). If the impression is made purely as a relief resulting from the greater pressure on the paper where the high parts of the matrix touch, the seal is known as a dry seal; in other cases ink or another liquid or liquefied medium is used, in another color than the paper.

In most traditional forms of dry seal the design on the seal matrix is in intaglio (cut below the flat surface) and therefore the design on the impressions made is in relief (raised above the surface). The design on the impression will reverse (be a mirror-image of) that of the matrix, which is especially important when script is included in the design, as it very often is. This will not be the case if paper is embossed from behind, where the matrix and impression read the same way, and both matrix and impression are in relief. However engraved gems were often carved in relief, called cameo in this context, giving a "counter-relief" or intaglio impression when used as seals. The process is essentially that of a mould.

Most seals have always given a single impression on an essentially flat surface, but in medieval Europe two-sided seals with two matrices were often used by institutions or rulers (such as towns, bishops and kings) to make two-sided or fully three-dimensional impressions in wax, with a "tag", a piece of ribbon or strip of parchment, running through them. These "pendent" seal impressions dangled below the documents they authenticated, to which the attachment tag was sewn or otherwise attached (single-sided seals were treated in the same way).

Some jurisdictions consider rubber stamps or specified signature-accompanying words such as "seal" or "L.S." (abbreviation of locus sigilli, "place of the seal") to be the legal equivalent of, i.e., an equally effective substitute for, a seal.

In the United States, the word "seal" is sometimes assigned to a facsimile of the seal design (in monochrome or color), which may be used in a variety of contexts including architectural settings, on flags, or on official letterheads. Thus, for example, the Great Seal of the United States, among other uses, appears on the reverse of the one-dollar bill; and several of the seals of the U.S. states appear on their respective state flags. In Europe, although coats of arms and heraldic badges may well feature in such contexts as well as on seals, the seal design in its entirety rarely appears as a graphical emblem and is used mainly as originally intended: as an impression on documents.

The study of seals is known as sigillography or sphragistics.

Ancient Near East

Main article: Ancient Near Eastern seals and sealing practices

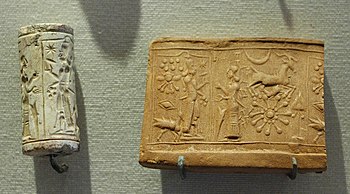

The stamp seal was a common seal die, frequently carved from stone, known at least since the 6th millennium BC (Halaf culture) and probably earlier. The oldest stamp seals were button-shaped objects with primitive ornamental forms chiseled onto them.

Main article: Cylinder seal

Seals were used in the earliest civilizations and are of considerable importance in archaeology and art history. In ancient Mesopotamia carved or engraved cylinder seals in stone or other materials were used. These could be rolled along to create an impression on clay (which could be repeated indefinitely), and used as labels on consignments of trade goods, or for other purposes. They are normally hollow and it is presumed that they were worn on a string or chain round the neck. Many have only images, often very finely carved, with no writing, while others have both. From ancient Egypt seals in the form of signet rings, including some with the names of kings, have been found; these tend to show only names in hieroglyphics.

Recently, seals datable to the Himyarite age have come to light in South Arabia. One example shows a name written in Aramaic (Yitsḥaq bar Ḥanina) engraved in reverse so as to read correctly in the impression.

Ancient Greece and Rome

| This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "seals" antiquity – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

From the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC until the Middle Ages, seals of various kinds were in production in the Aegean islands and mainland Greece. In the Early Minoan age these were formed of soft stone and ivory and show particular characteristic forms. By the Middle Minoan age a new set for seal forms, motifs and materials appear. Hard stone requires new rotary carving techniques. The Late Bronze Age is the time par excellence of the lens-shaped seal and the seal ring, which continued into the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods, in the form of pictorial engraved gems. These were a major luxury art form and became keenly collected, with King Mithridates VI of Pontus the first major collector according to Pliny the Elder. His collection fell as booty to Pompey the Great, who deposited it in a temple in Rome. Engraved gems continued to be produced and collected until the 19th century. Pliny also explained the significance of the signet ring, and how over time this ring was worn on the little finger.

East Asia

See also: Seal (East Asia) Front

Front InscriptionJoseon-era Korean royal seal with knob in the form of a turtle, late 16th-17th century, cast bronze with gilding, 6.98 x 15.24 x 15.24 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

InscriptionJoseon-era Korean royal seal with knob in the form of a turtle, late 16th-17th century, cast bronze with gilding, 6.98 x 15.24 x 15.24 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Known as yinzhang (Chinese: 印章) in Greater China, injang in Korea, inshō in Japan, ấn triện (or ấn chương) in Vietnam, seals have been used in East Asia as a form of written identification since the Qin dynasty (221 BC–). The seals of the Han dynasty were impressed in a soft clay, but from the Tang dynasty a red ink made from cinnabar was normally used. Even in modern times, seals, often known as "chops" in local colloquial English, are still commonly used instead of handwritten signatures to authenticate official documents or financial transactions. Both individuals and organizations have official seals, and they often have multiple seals in different sizes and styles for different situations. East Asian seals usually bear the names of the people or organizations represented, but they can also bear poems or personal mottoes. Sometimes both types of seals, or large seals that bear both names and mottoes, are used to authenticate official documents. Seals are so important in East Asia that foreigners who frequently conduct business there also commission the engraving of personal seals.

East Asian seals are carved from a variety of hard materials, including wood, soapstone, sea glass and jade. East Asian seals are traditionally used with a red oil-based paste consisting of finely ground cinnabar, which contrasts with the black ink traditionally used for the ink brush. Red chemical inks are more commonly used in modern times for sealing documents. Seal engraving is considered a form of calligraphy in East Asia. Like ink-brush calligraphy, there are several styles of engraving. Some engraving styles emulate calligraphy styles, but many styles are so highly stylized that the characters represented on the seal are difficult for untrained readers to identify. Seal engravers are considered artists, and, in the past, several famous calligraphers also became famous as engravers. Some seals, carved by famous engravers, or owned by famous artists or political leaders, have become valuable as historical works of art.

Because seals are commissioned by individuals and carved by artists, every seal is unique, and engravers often personalize the seals that they create. The materials of seals and the styles of the engraving are typically matched to the personalities of the owners. Seals can be traditional or modern, or conservative or expressive. Seals are sometimes carved with the owners' zodiac animals on the tops of the seals. Seals are also sometimes carved with images or calligraphy on the sides.

Although it is a utilitarian instrument of daily business in East Asia, westerners and other non-Asians seldom see Asian seals except on Asian paintings and calligraphic art. All traditional paintings in China, Japan, Korea, and the rest of East Asia are watercolor paintings on silk, paper, or some other surface to which the red ink from seals can adhere. East Asian paintings often bear multiple seals, including one or two seals from the artist, and the seals from the owners of the paintings.

East Asian seals are the predecessors to block printing.

Western tradition

There is a direct line of descent from the seals used in the ancient world, to those used in medieval and post-medieval Europe, and so to those used in legal contexts in the western world to the present day. Seals were historically most often impressed in sealing wax (often simply described as "wax"): in the Middle Ages, this generally comprised a compound of about two-thirds beeswax to one-third of some kind of resin, but in the post-medieval period the resin (and other ingredients) came to dominate. During the early Middle Ages seals of lead, or more properly "bullae" (from the Latin), were in common use both in East and West, but with the notable exception of documents ("bulls") issued by the Papal Chancery these leaden authentications fell out of favour in western Christendom. Byzantine Emperors sometimes issued documents with gold seals, known as Golden Bulls.

Wax seals were being used on a fairly regular basis by most western royal chanceries by about the end of the 10th century. In England, few wax seals have survived of earlier date than the Norman Conquest, although some earlier matrices are known, recovered from archaeological contexts: the earliest is a gold double-sided matrix found near Postwick, Norfolk, and dated to the late 7th century; the next oldest is a mid-9th-century matrix of a Bishop Ethilwald (probably Æthelwold, Bishop of East Anglia). The practice of sealing in wax gradually moved down the social hierarchy from monarchs and bishops to great magnates, to petty knights by the end of the 12th century, and to ordinary freemen by the middle of the 13th century. They also came to be used by a variety of corporate bodies, including cathedral chapters, municipalities, monasteries etc., to validate the acts executed in their name.

Traditional wax seals continue to be used on certain high-status and ceremonial documents, but in the 20th century they were gradually superseded in many other contexts by inked or dry embossed seals and by rubber stamps.

While many instruments formerly required seals for validity (e.g. deeds or covenants) it is now unusual in most countries in the west for private citizens to use seals. In Central and Eastern Europe, however, as in East Asia, a signature alone is considered insufficient to authenticate a document of any kind in business, and all managers, as well as many book-keepers and other employees, have personal seals, normally just containing text, with their name and their position. These are applied to all letters, invoices issued, and similar documents. In Europe these are today plastic self-inking stamps.

Notaries also still use seals on a daily basis. At least in Britain, each registered notary has an individual personal seal, registered with the authorities, which includes his or her name and a pictorial emblem, often an animal—the same combination found in many seals from ancient Greece.

Practices

Seals are used primarily to authenticate documents, specifically those which carry some legal import. There are two main ways in which a seal may be attached to a document. It may be applied directly to the face of the paper or parchment (an applied seal); or it may hang loose from it (a pendent seal). A pendent seal may be attached to cords or ribbons (sometimes in the owner's livery colors), or to the two ends of a strip (or tag) of parchment, threaded through holes or slots cut in the lower edge of the document: the document is often folded double at this point (a plica) to provide extra strength. Alternatively, the seal may be attached to a narrow strip of the material of the document (again, in this case, usually parchment), sliced and folded down, as a tail or tongue, but not detached. The object in all cases is to help ensure authenticity by maintaining the integrity of the relationship between document and seal, and to prevent the seal's reuse. If a forger tries to remove an applied seal from its document, it will almost certainly break. A pendent seal is easily detached by cutting the cords or strips of parchment, but the forger would then have great difficulty in attaching it to another document (not least because the cords or parchment are normally knotted inside the seal), and would again almost certainly break it.

In the Middle Ages, the majority of seals were pendent. They were attached both to legal instruments and to letters patent (i.e. open letters) conferring rights or privileges, which were intended to be available for all to view. In the case of important transactions or agreements, the seals of all parties to the arrangement as well as of witnesses might be attached to the document, and so once executed it would carry several seals. Most governments still attach pendent seals to letters patent.

Applied seals, by contrast, were originally used to seal a document closed: that is to say, the document would be folded and the seal applied in such a way that the item could not be opened without the seal being broken. Applied seals were used on letters close (letters intended only for the recipient) and parcels to indicate whether or not the item had been opened or tampered with since it had left the sender, as well as providing evidence that the item was actually from the sender and not a forgery. In the post-medieval period, seals came to be commonly used in this way for private letters. A letter writer would fold the completed letter, pour wax over the joint formed by the top of the page, and then impress a ring or other seal matrix. Governments sometimes sent letters to citizens under the governmental seal for their eyes only, known as letters secret. Wax seals might also be used with letterlocking techniques to ensure that only the intended recipient would read the message. In general, seals are no longer used in these ways except for ceremonial purposes. However, applied seals also came to be used on legal instruments applied directly to the face of the document, so that there was no need to break them, and this use continues.

Designs

Historically, the majority of seals were circular in design, although ovals, triangles, shield-shapes and other patterns are also known. The design generally comprised a graphic emblem (sometimes, but not always, incorporating heraldic devices), surrounded by a text (the legend) running around the perimeter. The legend most often consisted merely of the words "The seal of ", either in Latin or in the local vernacular language: the Latin word Sigillum was frequently abbreviated to a simple S:. Occasionally, the legend took the form of a motto.

In the Middle Ages it became customary for the seals of women and of ecclesiastics to be given a vesica (pointed oval) shape. The central emblem was often a standing figure of the owner, or (in the case of ecclesiastical seals) of a saint. Medieval townspeople used a wide variety of different emblems but some had seals that included an image relating to their work.

Sealing wax was naturally yellowish or pale brownish in tone, but could also be artificially colored red or green (with many intermediary variations). In some medieval royal chanceries, different colours of wax were customarily used for different functions or departments of state, or to distinguish grants and decrees made in perpetuity from more ephemeral documents.

The matrices for pendent seals were sometimes accompanied by a smaller counter-seal, which would be used to impress a small emblem on the reverse of the impression. In some cases the seal and counter-seal would be kept by two different individuals, in order to provide an element of double-checking to the process of authentication. Sometimes, a large official seal, which might be in the custody of chancery officials, would need to be counter-sealed by the individual in whose name it had been applied (the monarch, or the mayor of a town): such a counter-seal might be carried on the person (perhaps secured by a chain or cord), or later, take the form of a signet ring, and so would be necessarily smaller. Other pendent seals were double-sided, with elaborate and equally-sized obverses and reverses. The impression would be formed by pressing a "sandwich" of matrices and wax firmly together by means of rollers or, later, a lever-press or a screw press. Certain medieval seals were more complex still, involving two levels of impression on each side of the wax which would be used to create a scene of three-dimensional depth.

On the death of a seal-holder, as a sign of continuity, a son and heir might commission a new seal employing the same symbols and design-elements as those used by his father. It is likely that this practice was a factor in the emergence of hereditary heraldry in western Europe in the 12th century.

Ecclesiasticism

Ecclesiastical seals are frequently mandorla-shaped, as in the shape of an almond, also known as vesica-shaped. The use of a seal by men of wealth and position was common before the Christian era, but high functionaries of the Church adopted the habit.

An incidental allusion in one of St. Augustine's letters (217 to Victorinus) indicates that he used a seal. The practice spread, and it seems to be taken for granted by King Clovis I at the very beginning of the Merovingian dynasty.

Later ecclesiastical synods require that letters under the bishop's seal should be given to priests when for some reason they lawfully quit their own proper diocese. Such a ruling was enacted at Chalon-sur-Saône in 813. Pope Nicholas I in the same century complained that the bishops of Dôle and Reims had, "contra morem" (contrary to custom), sent their letters to him unsealed. The custom of bishops possessing seals may from this date be assumed to have been pretty general.

In the British Museum collection the earliest bishop's seals preserved are those of William de St-Calais, Bishop of Durham (1081–96) and of St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (1093–1109).

Architects, surveyors and professional engineers

Seals are also affixed on architectural or engineering construction documents, or land survey drawings, to certify the identity of the licensed professional who supervised the development. Depending on the authority having jurisdiction for the project, these seals may be embossed and signed, stamped and signed, or in certain situations a computer generated facsimile of the original seal validated by a digital certificate owned by the professional may be attached to a security protected computer file. The identities on the professional seals determine legal responsibility for any errors or omissions, and in some cases financial responsibility for their correction as well as the territory of their responsibility, e.g.: "State of Minnesota".

In some jurisdictions, especially in Canada, it is a legal requirement for a professional engineer to seal documents in accordance with the Engineering Profession Act and Regulations. Professional engineers may also be legally entitled to seal any document they prepare. The seal identifies work performed by, or under the direct supervision of, a licensed professional engineer, and assures the document's recipient that the work meets the standards expected of experienced professionals who take personal responsibility for their judgments and decisions.

Custom houses

In old English law, a cocket was a custom house seal; or a certified document given to a shipper as a warrant that his goods have been duly entered and have paid duty. Hence, in Scotland, there was an officer called the clerk of the cocket. It may have given its name to cocket bread, which was perhaps stamped as though with a seal.

Destruction

The importance of the seal as a means of authentication necessitated that when authority passed into new hands the old seal should be destroyed and a new one made. When the pope dies it is the first duty of the Cardinal Camerlengo to obtain possession of the Ring of the Fisherman, the papal signet, and to see that it is broken up. A similar practice prevailed in the Middle Ages and it is often alluded to by historians, as it seems to have been a matter of some ceremony. For example, on the death of Robert of Holy Island, Bishop of Durham, in 1283, the chronicler Robert Greystones reports: "After his burial, his seal was publicly broken up in the presence of all by Master Robert Avenel." Matthew Paris gives a similar description of the breaking of the seal of William of Trumpington, Abbot of St Albans, in 1235.

The practice is less widely attested in the case of medieval laypeople, but certainly occurred on occasion, particularly in the 13th and 14th centuries. Silver seal matrices have been found in the graves of some of the 12th-century queens of France. These were probably deliberately buried as a means of cancelling them.

When King James II of England was dethroned in the Glorious Revolution of 1688/9, he is supposed to have thrown the Great Seal of the Realm into the River Thames before his flight to France in order to ensure that the machinery of government would cease to function. It is unclear how much truth there is to this story, but certainly the seal was recovered: James's successors, William III and Mary used the same Great Seal matrix, fairly crudely adapted – possibly quite deliberately, in order to demonstrate the continuity of government.

Signet rings

A signet ring is a ring bearing on its flat top surface the equivalent of a seal. A typical signet ring has a design, often a family or personal crest, created in intaglio so that it will leave a raised (relief) impression of the design when the ring is pressed onto liquid sealing wax. The design is often made out of agate, carnelian, or sardonyx which tend not to bind with the wax. Most smaller classical engraved gems were probably originally worn as signet rings, or as seals on a necklace.

The wearing of signet rings (from Latin "signum" meaning "sign" or "mark") dates back to ancient Egypt: the seal of a pharaoh is mentioned in the Book of Genesis. Genesis 41:42: "Removing his signet ring from his hand, Pharaoh put it on Joseph's hand; he arrayed him in garments of fine linen, and put a gold chain around his neck."

Because it is used to attest to the authority of its bearer, the ring has also been seen as a symbol of power, which is why it is included in the regalia of certain monarchies. After the death of a Pope, the destruction of his signet ring is a prescribed act clearing the way for the sede vacante and subsequent election of a new Pope.

Signet rings are also used as a souvenir or membership attribute, e.g., class rings (which typically bear the coat of arms or crest of the school). One may also have their initials engraved as a sign of their personal stature. Traditionally, signet rings were worn either on the little or the ring finger of the least dominant hand, with the most common usage being on the little.

The less noble classes began wearing and using signet rings as early as the 13th century. In the 17th century, signet rings fell out of favor in the upper levels of society, replaced by other means for mounting and carrying the signet. In the 18th century, though, signet rings again became popular, and by the 19th century, men of all classes wore them.

Since at least the 16th century there have also been pseudo-signet rings where the engraving is not reversed (mirror image), as it should be if the impression is to read correctly.

Rings have been used since antiquity as spy identification and in espionage. During World War II, US Air Force personnel would privately purchase signet rings with a hidden compartment that would hold a small compass or hidden message. MI9 purchased a number of signet rings from Regent Street jewelers that were used to conceal compasses.

Modern tamper-proofing

In modern use, seals are used to tamper-proof equipment. For example, to prevent gas and electricity meters from being interfered with to show lower chargeable readings, they may be sealed with a lead or plastic seal with a government marking, typically fixed to a wire that passes through part of the meter housing. The meter cannot be opened without cutting the wire or damaging the seal.

Specially-made tamper-evident labels are available which are destroyed if the protected container or equipment is opened, functionally equivalent to a wax seal. They are used to protect things which must not be tampered with such as pharmaceuticals, equipment whose opening voids a manufacturer's warranty, etc.

Figurative uses

Approval

See also: Certification markThe expression "seal of approval" refers to a formal approval, regardless whether it involves a seal or other external marking, by an authoritative person or institute.

It is also part of the formal name of certain quality marks, such as:

- Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval of the Good Housekeeping Institute

- Good Netkeeping Seal of Approval

See also

- Company seal

- Keeper of the seal

- Great seal

- King of Na gold seal, the first seal in Japan

- Knights Templar Seal used to validate documents approved by the order

- Manu propria

- Privy seal

- Signet ring cell

References

- New 2010, p. 7.

- Notary Public Handbook. (2020). California Secretary of State, Notary Public Section. p. 7.

- Vermont Statutes Title 1 § 134. Vermont Legislature. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- Brown & Feldman 2013, p. 304.

- Di Palma 2015, p. 21.

- Harris Rackham (1938). "Pliny The Elder, Natural History". Loeb Classical Library.

- Thomas Carter (1925). The invention of printing in China. Columbia University Press.

- Jenkinson 1968, p. 12.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbert Thurston (1913). "Seal". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbert Thurston (1913). "Seal". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Signet Ring". The Walters Art Museum.

- New 2010, p. 3.

- Jenkinson 1968, pp. 6–7.

- Jenkinson 1968, pp. 14–18.

- New 2010, pp. 19–23.

- Jenkinson 1968, pp. 18–19.

- Cain, Abigal (9 November 2018). "Before Envelopes, People Protected Messages With Letterlocking". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "British Museum Collection".

- McEwan 2016, no.764.

- Jenkinson 1968, p. 13.

- New 2010, p. 41.

- John A. McEwan, "Does size matter? Seals in England and Wales, ca. 1200–1500", in Whatley 2019, pp. 103–26 (116–18).

- Jenkinson 1968, pp. 8–10.

- New 2010, p. 13.

- John Cherry, "Medieval and post-medieval seals", in Collon 1997, pp. 130–131.

- Markus Späth, "Memorialising the glorious past: thirteenth-century seals from English cathedral priories and their artistic contexts", in Schofield 2015, p. 166.

- Wagner, Anthony (1956). Heralds and Heraldry in the Middle Ages (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13–15.

- Brooke-Little, John (1973). Boutell's Heraldry. London: Frederick Warne. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-7232-1708-4.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leg., II, 2.

- Philipp Jaffé, Regesta Pontificum Romanorum, nos. 2789, 2806, 2823.

- "What is a PE" National Society of Professional Engineers (US).

- "How Building Officials Interact With Registered Architects And Engineers" National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (US).

- GSA P100 Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service. Appendix A: "Submission Requirements" Archived 2009-09-29 at the Wayback Machine U.S. General Services Administration.

- "Rule and Regulation Change Allowing the Construction and use of Computerized Seals" Archived 2009-10-11 at the Wayback Machine Kansas State Board of Technical Professions. Typical sample of requirements for a professional seal in the United States.

- FAR 36.609 Archived 2010-12-01 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Federal Acquisition Regulations, Subpart 36.6 Architect-Engineer Services, Article 36.609 Contract Clauses.

- Cocket, History of Science and Technology. p.243

- "Cocket". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2nd ed. 1989.

- Raine, James, ed. (1839). Historia Dunelmensis Scriptores Tres. Surtees Society. Vol. 9. London. p. 63.

- Cherry 1992.

- Paul Brand, "Seals and the law in the thirteenth century", in Schofield 2015, pp. 111–19 (at p. 115).

- Cherry, "Medieval and post-medieval seals", in Collon 1997, p. 134.

- Dąbrowska, Elżbieta (2011). "Les sceaux et les matrices de sceaux trouvés dans le tombes médiévales". In Gil, Marc; Chassel, Jean-Luc (eds.). Pourquois les sceaux? La sigillographie, nouvel enjeu de l'histoire de l'art. Lille: Centre de Gestion de l'Édition Scientifique. pp. 31–43.

- Jenkinson, Hilary (1943). "What happened to the Great Seal of James II?". Antiquaries Journal. 23 (1–2): 1–13. doi:10.1017/s0003581500042189. S2CID 162188010.

- "What Is A Signet Ring And Why Wear One?". He Spoke Style. 31 May 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "The ultimate guide to signet rings / Journal". Rebus Signet Rings. 2017-06-20. Archived from the original on 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978). Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. Ashmolean Museum. p. 71. ISBN 0-900090-54-5.

- Froom, Phil. Evasion and Escape Devices: Produced by MI9, MIS-X and SOE in World War II. 2015. Pages 296–297.

- "Gas meter stamping". UK Government. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- "Publication of specifications related to physical sealing of electricity and gas meters". Measurement Canada. 18 August 2008.

- Corbin, Tony (15 November 2018). "Tamper evident labels market growth continues". Packaging News.

Bibliography

- Adams, Noël; Cherry, John; Robinson, James, eds. (2007). Good Impressions: Image and Authority in Medieval Seals. British Museum Research Publications 168. London: British Museum. ISBN 978-0-86159-168-8.

- Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer, eds. (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: case studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107194588.

- Boardman, John (1972). Greek Gems and Finger Rings. New York: New York, H.N. Abrams.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9781614510352.

- Chassel, Jean-Luc (2003). Sceaux et usages de sceaux: images de la Champagne médiévale. Paris: Somogny. ISBN 2-85056-643-8.

- Cherry, John (1992). "The breaking of seals". Medieval Europe 1992: pre-printed papers: vol. 7: Art and Symbolism. York: Medieval Europe 1992. pp. 23–27. ISBN 0952002361.

- Cherry, John; Berenbeim, Jessica; Beer, Lloyd de, eds. (2018). Seals and Status: power of objects. British Museum Research Publication. Vol. 213. London: British Museum. ISBN 9780861592135.

- Di Palma, Salvatore (2015). The History of Marks from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Société des écrivains.

- Collon, Dominique, ed. (1997). 7000 Years of Seals. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-1143-0.

- Grisar, Josef; De Lasala, Fernando (1997). Aspetti della sigillografia. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Harvey, P. D. A.; McGuinness, Andrew (1996). A Guide to British Medieval Seals. London: British Library and Public Record Office. ISBN 0-7123-0410-X.

- Jenkinson, Hilary (1968). Guide to Seals in the Public Record Office. Public Record Handbooks. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- McEwan, John (2016). Seals in Medieval London, 1050–1300: A Catalogue. London Record Society Extra Series. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-900952-56-2.

- Morris, David (2012). Matrix: A Collection of British Seals. Whyteleaf. ISBN 978-0-9570102-0-8.

- New, Elizabeth (2010). Seals and Sealing Practices. Archives and the User. Vol. 11. London: British Records Association. ISBN 978-0-900222-15-3.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1981). Les sceaux. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Posse, Otto (1913). Die Siegel der deutschen Kaiser und Könige, von 751 bis 1913. Vol. 5. Dresden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Accessible on Wikisource - Schofield, Phillipp R., ed. (2015). Seals and their Context in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxbow. ISBN 978-1-78297-817-6.

- Schofield, P. R.; New, E. A., eds. (2016). Seals and Society: medieval Wales, the Welsh marches and their English border region. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9781783168712.

- Whatley, Laura, ed. (2019). A Companion to Seals in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-38064-6.

- Yule, Paul (1981). Early Cretan Seals: A Study of Chronology. Marburger Studien zur Vor und Frühgeschichte 4. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-0490-0.

- Živković, Tibor (2007). "The Golden Seal of Stroimir" (PDF). Historical Review. 55. Belgrade: The Institute for History: 23–29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Cocket". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Cocket". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

External links

Works related to Seals at Wikisource

Works related to Seals at Wikisource

- God's Regents on Earth: A Thousand Years of Byzantine Imperial Seals, from the Dumbarton Oaks Collection

- UK National Archives on seals

- Not All Online Authority Seals are Credible - Harvard's Ben Edelman says "Suppose users have seen a seal on dozens of sites that turn out to be legitimate. Dubious sites can present that same seal to encourage more users to buy, register, or download."

- Signet ring article - Berganza, London: Signets: Sealed with a Ring

- Search Results (database of Byzantine Seal impressions from Prosopography of the Byzantine World project (PBW)

- Photographic reproductions of medieval seals in the Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden searchable via the verteillte Bildarchiv prometheus

| Heraldry | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | |||||||||||||||

| Topics | |||||||||||||||

| Achievement | |||||||||||||||

| Charges | |||||||||||||||

| Tinctures |

| ||||||||||||||

| Applications | |||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||