In cartography, the normal cylindrical equal-area projection is a family of normal cylindrical, equal-area map projections.

History

The invention of the Lambert cylindrical equal-area projection is attributed to the Swiss mathematician Johann Heinrich Lambert in 1772. Variations of it appeared over the years by inventors who stretched the height of the Lambert and compressed the width commensurately in various ratios.

Description

The projection:

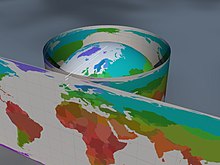

- is cylindrical, that means it has a cylindrical projection surface

- is normal, that means it has a normal aspect

- is an equal-area projection, that means any two areas in the map have the same relative size compared to their size on the sphere.

The term "normal cylindrical projection" is used to refer to any projection in which meridians are mapped to equally spaced vertical lines and circles of latitude are mapped to horizontal lines (or, mutatis mutandis, more generally, radial lines from a fixed point are mapped to equally spaced parallel lines and concentric circles around it are mapped to perpendicular lines).

The mapping of meridians to vertical lines can be visualized by imagining a cylinder whose axis coincides with the Earth's axis of rotation, then projecting onto the cylinder, and subsequently unfolding the cylinder.

By the geometry of their construction, cylindrical projections stretch distances east-west. The amount of stretch is the same at any chosen latitude on all cylindrical projections, and is given by the secant of the latitude as a multiple of the equator's scale. The various cylindrical projections are distinguished from each other solely by their north-south stretching (where latitude is given by φ):

The only normal cylindrical projections that preserve area have a north-south compression precisely the reciprocal of east-west stretching (cos φ). This divides north-south distances by a factor equal to the secant of the latitude, preserving area but distorting shapes.

East–west scale matching the north–south scale

Depending on the stretch factor S, any particular cylindrical equal-area projection either has zero, one or two latitudes for which the east–west scale matches the north–south scale.

- S>1 : zero

- S=1 : one, that latitude is the equator

- S<1 : a pair of identical latitudes of opposite sign

Formulae

The formulae presume a spherical model and use these definitions:

- λ is the longitude

- λ0 is the central meridian

- φ is the latitude

- φ0 is the standard latitude

- S is the stretch factor

- x is the horizontal coordinate of the projected location on the map

- y is the vertical coordinate of the projected location on the map

| using standard latitude φ0 | using stretch factor S | S=1, φ0=0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| using radians | |||

| using degrees |

Relationship between and :

Specializations

The specializations differ only in the ratio of the vertical to horizontal axis. Some specializations have been described, promoted, or otherwise named.

| Stretch factor S |

Aspect ratio (width-to-height) πS |

Standard parallel(s) φ0 |

Image (Tissot's indicatrix) | Image (Blue Marble) | Name | Publisher | Year of publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

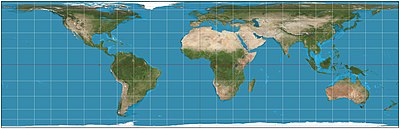

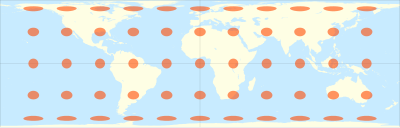

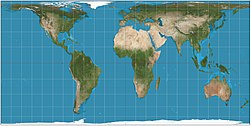

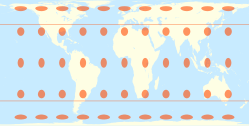

| 1 | π ≈ 3.142 | 0° |

|

|

Lambert cylindrical equal-area | Johann Heinrich Lambert | 1772 |

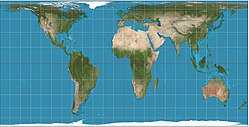

| 3/4 = 0.75 |

3π/4 ≈ 2.356 | 30° |

|

|

Behrmann | Walter Behrmann | 1910 |

| 2/π ≈ 0.6366 |

2 | ≈ 37°04′17″ ≈ 37.0714° |

|

|

Smyth equal-surface = Craster rectangular |

Charles Piazzi Smyth | 1870 |

| cos(37.4°) ≈ 0.6311 |

π·cos(37.4°) ≈ 1.983 |

37°24′ = 37.4° |

|

|

Trystan Edwards | Trystan Edwards | 1953 |

| cos(37.5°) ≈ 0.6294 |

π·cos(37.5°) ≈ 1.977 |

37°30′ = 37.5° |

|

|

Hobo–Dyer | Mick Dyer | 2002 |

| cos(40°) ≈ 0.5868 |

π·cos(40°) ≈ 1.844 |

40° |

|

|

(unnamed) | ||

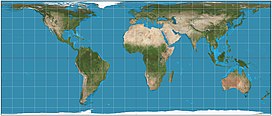

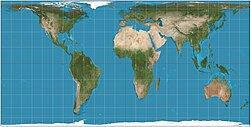

| 1/2 =0.5 |

π/2 ≈ 1.571 | 45° |

|

|

Gall–Peters = Gall orthographic = Peters |

James Gall, Promoted by Arno Peters as his own invention |

1855 (Gall), 1967 (Peters) |

| cos(50°) ≈ 0.4132 |

π·cos(50°) ≈ 1.298 |

50° |

|

|

Balthasart | M. Balthasart | 1935 |

| 1/π ≈ 0.3183 |

1 | ≈ 55°39′14″ ≈ 55.6540° |

|

|

Tobler's world in a square | Waldo Tobler | 1986 |

Derivatives

The Tobler hyperelliptical projection, first described by Tobler in 1973, is a further generalization of the cylindrical equal-area family.

The HEALPix projection is an equal-area hybrid combination of: the Lambert cylindrical equal-area projection, for the equatorial regions of the sphere; and an interrupted Collignon projection, for the polar regions.

References

- Mulcahy, Karen. "Cylindrical Projections". City University of New York. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- "Cylindrical projection | cartography | Britannica".

- Map Projections – A Working Manual Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, USGS Professional Paper 1395, John P. Snyder, 1987, pp.76–85

- Snyder, John P. (1989). An Album of Map Projections p. 19. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1453. (Mathematical properties of the Gall–Peters and related projections.)

- Monmonier, Mark (2004). Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection p. 152. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Thorough treatment of the social history of the Mercator projection and Gall–Peters projections.)

- Smyth, C. Piazzi. (1870). On an Equal-Surface Projection and its Anthropological Applications. Edinburgh: Edmonton & Douglas. (Monograph describing an equal-area cylindric projection and its virtues, specifically disparaging Mercator's projection.)

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Cylindrical Equal-Area Projection." From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/CylindricalEqual-AreaProjection.html

- Tobler, Waldo and Chen, Zi-tan(1986). A Quadtree for Global Information Storage. http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/~kclarke/Geography232/Tobler1986.pdf

External links

- Table of examples and properties of all common projections, from radicalcartography.net

and

and  :

: