| Marathi | |

|---|---|

| Marāṭhī | |

| मराठी, 𑘦𑘨𑘰𑘙𑘲 | |

| Pronunciation | Marathi: [məˈɾaːʈʰiː] English: /məˈrɑːti/ |

| Native to | India |

| Region | South and Western India

|

| Ethnicity | Marathi |

| Speakers | L1: 83 million (2011) L2: 16 million (2011) |

| Language family | Indo-European |

| Early form | Maharashtri Prakrit |

| Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

| Writing system |

|

| Signed forms | Indian Signing System |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | India

|

| Recognised minority language in | India |

| Regulated by | Ministry of Marathi Language and various other institutions |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mr |

| ISO 639-2 | mar |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:mar – Modern Marathiomr – Old Marathi |

| Linguist List | omr Old Marathi |

| Glottolog | mara1378 Modern Marathioldm1244 Old Marathi |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-o |

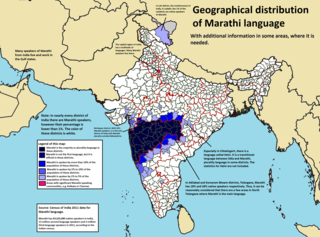

regions where Marathi is the language of the majority or plurality regions where Marathi is the language of a significant minority regions where Marathi is the language of the majority or plurality regions where Marathi is the language of a significant minority | |

Map of Marathi language in India (district-wise). Darker shades imply a greater percentage of native speakers of Marathi in each district. Map of Marathi language in India (district-wise). Darker shades imply a greater percentage of native speakers of Marathi in each district. | |

Marathi (/məˈrɑːti/; मराठी, Marāṭhī, pronounced [məˈɾaːʈʰiː] ) is a classical Indo-Aryan language predominantly spoken by Marathi people in the Indian state of Maharashtra and is also spoken in other states like in Goa, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and the territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. It is the official language of Maharashtra, and an additional official language in the state of Goa, where it is used for replies, when requests are received in Marathi. It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India, with 83 million speakers as of 2011. Marathi ranks 13th in the list of languages with most native speakers in the world. Marathi has the third largest number of native speakers in India, after Hindi and Bengali. The language has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indian languages. The major dialects of Marathi are Standard Marathi and the Varhadi Marathi. Marathi was designated as a classical language by the Government of India in October 2024.

Marathi distinguishes inclusive and exclusive forms of 'we' and possesses three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Its phonology contrasts apico-alveolar with alveopalatal affricates and alveolar with retroflex laterals ( and (Marathi letters ल and ळ respectively).

History

See also: Marathi literature

Indian languages, including Marathi, that belong to the Indo-Aryan language family are derived from early forms of Prakrit. Marathi is one of several languages that further descend from Maharashtri Prakrit. Further changes led to the formation of Apabhraṃśa followed by Old Marathi. However, this is challenged by Bloch (1970), who states that Apabhraṃśa was formed after Marathi had already separated from the Middle Indian dialect.

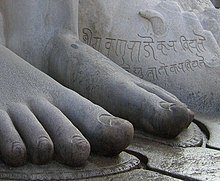

The earliest example of Marathi as a separate language dates to approximately 3rd century BCE: a stone inscription found in a cave at Naneghat, Junnar in Pune district had been written in Maharashtri using Brahmi script. The Gaha Sattasai is an ancient collection of poems composed approximately 2,000 years ago in ancient Marathi also known as Maharashtri Prakrit or simply Maharashtri. It is a collection of poetry attributed to the Satavahana King Hala. A committee appointed by the Maharashtra State Government to get the Classical status for Marathi has claimed that Marathi existed at least 2,300 years ago . Marathi, a derivative of Maharashtri Prakrit language, is probably first attested in a 739 CE copper-plate inscription found in Satara. Several inscriptions dated to the second half of the 11th century feature Marathi, which is usually appended to Sanskrit or Kannada in these inscriptions. The earliest Marathi-only inscriptions are the ones issued during the Shilahara rule, including a c. 1012 CE stone inscription from Akshi taluka of Raigad district, and a 1060 or 1086 CE copper-plate inscription from Dive that records a land grant (agrahara) to a Brahmin. A 2-line 1118 CE Prakrit inscription at Shravanabelagola records a grant by the Hoysalas. These inscriptions suggest that Prakrit was a standard written language by the 12th century. However, after the Gaha Sattasai there is no record of any literature produced in Marathi until the late 13th century.

Yadava period

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Marathi language" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

After 1187 CE, the use of Marathi grew substantially in the inscriptions of the Yadava kings, who earlier used Kannada and Sanskrit in their inscriptions. Marathi became the dominant language of epigraphy during the last half century of the dynasty's rule (14th century), and may have been a result of the Yadava attempts to connect with their Marathi-speaking subjects and to distinguish themselves from the Kannada-speaking Hoysalas.

Further growth and usage of the language was because of two religious sects – the Mahanubhava and Varkari panthans – who adopted Marathi as the medium for preaching their doctrines of devotion. Marathi was used in court life by the time of the Yadava kings. During the reign of the last three Yadava kings, a great deal of literature in verse and prose, on astrology, medicine, Puranas, Vedanta, kings and courtiers were created. Nalopakhyana, Rukminiswayamvara and Shripati's Jyotisharatnamala (1039) are a few examples.

The oldest book in prose form in Marathi, Vivēkasindhu (विवेकसिंधु), was written by Mukundaraja, a Nath yogi and arch-poet of Marathi. Mukundaraja bases his exposition of the basic tenets of the Hindu philosophy and the yoga marga on the utterances or teachings of Shankaracharya. Mukundaraja's other work, Paramamrta, is considered the first systematic attempt to explain the Vedanta in the Marathi language

Notable examples of Marathi prose are "Līḷācarītra" (लीळाचरित्र), events and anecdotes from the miracle-filled the life of Chakradhar Swami of the Mahanubhava sect compiled by his close disciple, Mahimbhatta, in 1238. The Līḷācarītra is thought to be the first biography written in the Marathi language. Mahimbhatta's second important literary work is the Shri Govindaprabhucharitra or Ruddhipurcharitra, a biography of Shri Chakradhar Swami's guru, Shri Govind Prabhu. This was probably written in 1288. The Mahanubhava sect made Marathi a vehicle for the propagation of religion and culture. Mahanubhava literature generally comprises works that describe the incarnations of gods, the history of the sect, commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita, poetical works narrating the stories of the life of Krishna and grammatical and etymological works that are deemed useful to explain the philosophy of sect.

Medieval and Deccan Sultanate period

The 13th century Varkari saint Dnyaneshwar (1275–1296) wrote a treatise in Marathi on Bhagawat Gita popularly called Dnyaneshwari and Amrutanubhava.

Mukund Raj was a poet who lived in the 13th century and is said to be the first poet who composed in Marathi. He is known for the Viveka-Siddhi and Parammruta which are metaphysical, pantheistic works connected with orthodox Vedantism.

The 16th century saint-poet Eknath (1528–1599) is well known for composing the Eknāthī Bhāgavat, a commentary on Bhagavat Purana and the devotional songs called Bharud. Mukteshwar translated the Mahabharata into Marathi; Tukaram (1608–49) transformed Marathi into a rich literary language. His poetry contained his inspirations. Tukaram wrote over 3000 abhangs or devotional songs. Manmathswamy(1561-1631) wrote a large volume of poetry and literature in Marathi. The Shivparv Ambhag composed by him is still read with interest by Veerashaiva people of Marathwada. Apart from this, the Pararamrhasya, a spiritual book composed by him on Shatsthalsiddhanta, is also recited.

Marathi was widely used during the Sultanate period. Although the rulers were Muslims, the local feudal landlords and the revenue collectors were Hindus and so was the majority of the population. To simplify administration and revenue collection, the sultans promoted use of Marathi in official documents. However, the Marathi language from the era is heavily Persianised in its vocabulary. The Persian influence continues to this day with many Persian derived words used in everyday speech such as bāg (Garden), kārkhānā (factory), shahar (city), bāzār (market), dukān (shop), hushār (clever), kāḡaḏ (paper), khurchi (chair), jamin (land), jāhirāt (advertisement), and hazār (thousand) Marathi also became language of administration during the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. Adilshahi of Bijapur also used Marathi for administration and record keeping.

Maratha Confederacy

Marathi gained prominence with the rise of the Maratha Kingdom beginning with the reign of Shivaji. In his court, Shivaji replaced Persian, the common courtly language in the region, with Marathi. The Marathi language used in administrative documents also became less Persianised. Whereas in 1630, 80% of the vocabulary was Persian, it dropped to 37% by 1677. His reign stimulated the deployment of Marathi as a tool of systematic description and understanding. Shivaji Maharaj commissioned one of his officials, Balaji Avaji Chitnis, to make a comprehensive lexicon to replace Persian and Arabic terms with their Sanskrit equivalents. This led to production of 'Rājavyavahārakośa', the thesaurus of state usage in 1677.

Subsequent Maratha rulers extended the confederacy. These excursions by the Marathas helped to spread Marathi over broader geographical regions. This period also saw the use of Marathi in transactions involving land and other business. Documents from this period, therefore, give a better picture of the life of common people. There are a number of Bakhars (journals or narratives of historical events) written in Marathi and Modi script from this period.

In the 18th century during Peshwa rule, some well-known works such as Yatharthadeepika by Vaman Pandit, Naladamayanti Swayamvara by Raghunath Pandit, Pandava Pratap, Harivijay, Ramvijay by Shridhar Pandit and Mahabharata by Moropant were produced. Krishnadayarnava and Sridhar were poets during the Peshwa period. New literary forms were successfully experimented with during the period and classical styles were revived, especially the Mahakavya and Prabandha forms. The most important hagiographies of Varkari Bhakti saints were written by Mahipati in the 18th century. Other well known literary scholars of the 17th century were Mukteshwar and Shridhar. Mukteshwar was the grandson of Eknath and is the most distinguished poet in the Ovi meter. He is most known for translating the Mahabharata and the Ramayana in Marathi but only a part of the Mahabharata translation is available and the entire Ramayana translation is lost. Shridhar Kulkarni came from the Pandharpur area and his works are said to have superseded the Sanskrit epics to a certain extent. This period also saw the development of Powada (ballads sung in honour of warriors), and Lavani (romantic songs presented with dance and instruments like tabla). Major poet composers of Powada and Lavani songs of the 17th and the 18th century were Anant Phandi, Ram Joshi and Honaji Bala.

British colonial period

The British colonial period starting in early 1800s saw standardisation of Marathi grammar through the efforts of the Christian missionary William Carey. Carey's dictionary had fewer entries and Marathi words were in Devanagari. Translations of the Bible were the first books to be printed in Marathi. These translations by William Carey, the American Marathi mission and the Scottish missionaries led to the development of a peculiar pidginised Marathi called "Missionary Marathi" in the early 1800s. The most comprehensive Marathi-English dictionary was compiled by Captain James Thomas Molesworth and Major Thomas Candy in 1831. The book is still in print nearly two centuries after its publication. The colonial authorities also worked on standardising Marathi under the leadership of Molesworth and Candy. They consulted Brahmins of Pune for this task and adopted the Sanskrit dominated dialect spoken by the elite in the city as the standard dialect for Marathi.

The first Marathi translation of the New Testament was published in 1811 by the Serampore press of William Carey. The first Marathi newspaper called Durpan was started by Balshastri Jambhekar in 1832. Newspapers provided a platform for sharing literary views, and many books on social reforms were written. The First Marathi periodical Dirghadarshan was started in 1840. The Marathi language flourished, as Marathi drama gained popularity. Musicals known as Sangeet Natak also evolved. Keshavasut, the father of modern Marathi poetry published his first poem in 1885. The late-19th century in Maharashtra saw the rise of essayist Vishnushastri Chiplunkar with his periodical, Nibandhmala that had essays that criticised social reformers like Phule and Gopal Hari Deshmukh. He also founded the popular Marathi periodical of that era called Kesari in 1881. Later under the editorship of Lokmanya Tilak, the newspaper was instrumental in spreading Tilak's nationalist and social views. Phule and Deshmukh also started their periodicals, Deenbandhu and Prabhakar, that criticised the prevailing Hindu culture of the day. The 19th century and early 20th century saw several books published on Marathi grammar. Notable grammarians of this period were Tarkhadkar, A.K.Kher, Moro Keshav Damle, and R.Joshi

The first half of the 20th century was marked by new enthusiasm in literary pursuits, and socio-political activism helped achieve major milestones in Marathi literature, drama, music and film. Modern Marathi prose flourished: for example, N.C.Kelkar's biographical writings, novels of Hari Narayan Apte, Narayan Sitaram Phadke and V. S. Khandekar, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar's nationalist literature and plays of Mama Varerkar and Kirloskar. In folk arts, Patthe Bapurao wrote many lavani songs during the late colonial period.

Marathi since Indian independence in 1947

After Indian independence, Marathi was accorded the status of a scheduled language on the national level. In 1956, the then Bombay state was reorganised, which brought most Marathi and Gujarati speaking areas under one state. Further re-organization of the Bombay state on 1 May 1960, created the Marathi speaking Maharashtra and Gujarati speaking Gujarat state respectively. With state and cultural protection, Marathi made great strides by the 1990s. A literary event called Akhil Bharatiya Marathi Sahitya Sammelan (All-India Marathi Literature Meet) is held every year. In addition, the Akhil Bharatiya Marathi Natya Sammelan (All-India Marathi Theatre Convention) is also held annually. Both events are very popular among Marathi speakers.

Notable works in Marathi in the latter half of the 20th century include Khandekar's Yayati, which won him the Jnanpith Award. Also Vijay Tendulkar's plays in Marathi have earned him a reputation beyond Maharashtra. P.L. Deshpande (popularly known as PuLa), Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar, P.K. Atre, Prabodhankar Thackeray and Vishwas Patil are known for their writings in Marathi in the fields of drama, comedy and social commentary. Bashir Momin Kavathekar wrote Lavani's and folk songs for Tamasha artists.

In 1958 the term "Dalit literature" was used for the first time, when the first conference of Maharashtra Dalit Sahitya Sangha (Maharashtra Dalit Literature Society) was held at Mumbai, a movement inspired by 19th century social reformer, Jyotiba Phule and eminent dalit leader, Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar. Baburao Bagul (1930–2008) was a pioneer of Dalit writings in Marathi. His first collection of stories, Jevha Mi Jat Chorali (जेव्हा मी जात चोरली, "When I Stole My Caste"), published in 1963, created a stir in Marathi literature with its passionate depiction of a cruel society and thus brought in new momentum to Dalit literature in Marathi. Gradually with other writers like Namdeo Dhasal (who founded Dalit Panther), these Dalit writings paved way for the strengthening of Dalit movement. Notable Dalit authors writing in Marathi include Arun Kamble, Shantabai Kamble, Raja Dhale, Namdev Dhasal, Daya Pawar, Annabhau Sathe, Laxman Mane, Laxman Gaikwad, Sharankumar Limbale, Bhau Panchbhai, Kishor Shantabai Kale, Narendra Jadhav, Keshav Meshram, Urmila Pawar, Vinay Dharwadkar, Gangadhar Pantawane, Kumud Pawde and Jyoti Lanjewar.

In recent decades there has been a trend among Marathi speaking parents of all social classes in major urban areas of sending their children to English medium schools. There is some concern that this may lead to the marginalisation of the language.

Geographic distribution

Marathi is primarily spoken in Maharashtra and parts of neighbouring states of Gujarat (majorly in Vadodara, and among a small number of population in Surat), Madhya Pradesh (in the districts of Burhanpur, Betul, Chhindwara and Balaghat), Goa, Chhattisgarh, Tamil Nadu (in Thanjavur) and Karnataka (in the districts of Belagavi, Karwar, Bagalkote, Vijayapura, Kalaburagi and Bidar), Telangana, union-territories of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. The former Maratha ruled cities of Baroda, Indore, Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Tanjore have had sizeable Marathi-speaking populations for centuries. Marathi is also spoken by Maharashtrian migrants to other parts of India and overseas. For instance, the people from western India who emigrated to Mauritius in the early 19th century also speak Marathi.

There were 83 million native Marathi speakers in India, according to the 2011 census, making it the third most spoken native language after Hindi and Bengali. Native Marathi speakers form 6.86% of India's population. Native speakers of Marathi formed 70.34% of the population in Maharashtra, 10.89% in Goa, 7.01% in Dadra and Nagar Haveli, 4.53% in Daman and Diu, 3.38% in Karnataka, 1.7% in Madhya Pradesh, and 1.52% in Gujarat.

International

The following table is a list of the geographic distribution of Marathi speakers as it appears in the 2019 edition of Ethnologue, a language reference published by SIL International, which is based in the United States.

| Country | Speaker population | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13,100 | 2016 census | |

| 8,300 | 2016 census | |

| 23,000 | Leclerc 2018a | |

| 17,000 | Leclerc 2018c | |

| 2,900 | 2013 census | |

| 6,410 | 2011 census | |

| 73,600 | 2015 census |

Status

Marathi is the official language of Maharashtra and additional official language in the state of Goa. In Goa, Konkani is the sole official language; however, Marathi may also be used for any or all official purposes in case any request is received in Marathi. Marathi is included among the languages that are part of the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India, thus granting it the status of a "scheduled language". The Government of Maharashtra has applied to the Ministry of Culture to grant classical language status to Marathi language, which was approved by the Government of India on 3 October 2024.

The contemporary grammatical rules described by Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad and endorsed by the Government of Maharashtra are supposed to take precedence in standard written Marathi. Traditions of Marathi Linguistics and the above-mentioned rules give special status to tatsamas, words adapted from Sanskrit. This special status expects the rules for tatsamas to be followed as in Sanskrit. This practice provides Marathi with a large corpus of Sanskrit words to cope with the demands of new technical words whenever needed.

In addition to all universities in Maharashtra, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in Vadodara, Osmania University in Hyderabad, Karnataka University in Dharwad, Gulbarga University in Kalaburagi, Devi Ahilya University in Indore and Goa University in Goa have special departments for higher studies in Marathi linguistics. Jawaharlal Nehru University (New Delhi) has announced plans to establish a special department for Marathi.

Marathi Day is celebrated on 27 February, the birthday of the poet Kusumagraj (Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar).

Dialects

See also: Marathi-Konkani languagesStandard Marathi is based on dialects used by academics and the print media.

Indic scholars distinguish 42 dialects of spoken Marathi. Dialects bordering other major language areas have many properties in common with those languages, further differentiating them from standard spoken Marathi. The bulk of the variation within these dialects is primarily lexical and phonological (e.g. accent placement and pronunciation). Although the number of dialects is considerable, the degree of intelligibility within these dialects is relatively high.

Varhadi

Main article: Varhadi dialectVarhadi (Varhādi) (वऱ्हाडि) or Vaidarbhi (वैदर्भि) is spoken in the Western Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. In Marathi, the retroflex lateral approximant ḷ [ɭ] is common, while sometimes in the Varhadii dialect, it corresponds to the palatal approximant y (IPA: ), making this dialect quite distinct. Such phonetic shifts are common in spoken Marathi and, as such, the spoken dialects vary from one region of Maharashtra to another.

Zadi Boli

Zaadi Boli or Zhaadiboli (झाडिबोलि) is spoken in Zaadipranta (a forest rich region) of far eastern Maharashtra or eastern Vidarbha or western-central Gondwana comprising Gondia, Bhandara, Chandrapur, Gadchiroli and some parts of Nagpur of Maharashtra.

Zaadi Boli Sahitya Mandal and many literary figures are working for the conservation of this dialect of Marathi.

Southern Indian Marathi

Thanjavur Marathi तञ्जावूर् मराठि, Namadeva Shimpi Marathi, Arey Marathi (Telangana), Kasaragod (north Kerala) and Bhavsar Marathi are some of the dialects of Marathi spoken by many descendants of Maharashtrians who migrated to Southern India. These dialects retain the 17th-century basic form of Marathi and have been considerably influenced by the Dravidian languages after the migration. These dialects have speakers in various parts of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

Other

- Thanjavur Marathi, spoken in Tanjore, Tamil Nadu

- Judæo-Marathi, spoken by the Bene Israel Jews

- East Indian Marathi, spoken by the Indian Christian East Indian ethno-religious group

Other Marathi–Konkani languages and dialects spoken in Maharashtra include Maharashtrian Konkani, Malvani, Sangameshwari, Agri, Andh, Warli, Vadvali and Samavedi.

Phonology

Main article: Marathi phonologyVowels

Vowels in native words are:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Low | a |

There is almost no phonemic length distinction, even though it is indicated in the script. Some educated speakers try to maintain a length distinction in learned borrowings (tatsamas) from Sanskrit.

There are no nasal vowels, although some speakers of Puneri and Kokni dialects maintain nasalisation of vowels that was present in old Marathi and continues to be orthographically present in modern Marathi.

Marathi furthermore contrasts /əi, əu/ with /ai, au/.

There are two more vowels in Marathi to denote the pronunciations of English words such as of /æ/ in act and /ɔ/ in all. These are written as ⟨अॅ⟩ and ⟨ऑ⟩.

The default vowel has two allophones apart from ə. The most prevalent allophone is ɤ, which results in कळ (kaḷa) being more commonly pronounced as rather than . Another rare allophone is ʌ, which occurs in words such as महाराज (mahārāja): .

Marathi retains several features of Sanskrit that have been lost in other Indo-Aryan languages such as Hindi and Bengali, especially in terms of pronunciation of vowels and consonants. For instance, Marathi retains the original diphthong qualities of ⟨ऐ⟩ , and ⟨औ⟩ which became monophthongs in Hindi. However, similar to speakers of Western Indo-Aryan languages and Dravidian languages, Marathi speakers tend to pronounce syllabic consonant ऋ ṛ as , unlike Northern Indo-Aryan languages which changed it to (e.g. the original Sanskrit pronunciation of the language's name was saṃskṛtam, while in day-to-day Marathi it is saṃskrut. In other Indic languages, it is closer to sanskrit). Spoken Marathi allows for conservative stress patterns in words like शब्द (śabda) with an emphasis on the ending vowel sound, a feature that has been lost in Hindi due to Schwa deletion.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | (Alveolo-) palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | plain | m | n̪ | ɳ | (ɲ) | (ŋ) | ||

| murmured | mʱ | nʱ | ɳʱ | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t̪ | t͡s | ʈ | t͡ɕ~t͡ʃ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ~f | tʰ | ʈʰ | t͡ɕʰ~t͡ʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b | d̪ | d͡z~z | ɖ | d͡ʑ~d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||

| murmured | bʱ | dʱ | d͡zʱ~zʱ | ɖʱ | d͡ʑʱ~d͡ʒʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | s̪ | ʂ | ɕ~ʃ | h~ɦ | ||||

| Approximant | plain | ʋ | l | ɭ | j | |||

| murmured | ʋʱ | lʱ | (jʱ) | |||||

| Flap/Trill | plain | ɾ~r | (𝼈) | |||||

| murmured | ɾʱ~rʱ | |||||||

- Marathi used to have a /t͡sʰ/ but it merged with /s/.

- Some speakers pronounce /d͡z, d͡zʱ/ as fricatives but the aspiration is maintained in /zʱ/.

A defining feature of the Marathi language is the split of Indo-Aryan ल /la/ into a retroflex lateral flap ळ (ḷa) and alveolar ल (la). It shares this feature with Punjabi. For instance, कुळ (kuḷa) for the Sanskrit कुलम् (kulam, 'clan') and कमळ (kamaḷ) for Sanskrit कमलम् (kamalam 'lotus'). Marathi got ळ possibly due to long contact from Dravidian languages; there are some ḷ words loaned from Kannada like ṭhaḷak from taḷaku but most of the words are native. Vedic Sanskrit did have /ɭ, ɭʱ/ as well, but they merged with /ɖ, ɖʱ/ by the time of classical Sanskrit.

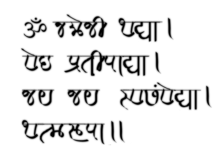

Writing

The Kadamba script and its variants have been historically used to write Marathi in the form of inscriptions on stones and copper plates. The Marathi version of Devanagari, called Balbodh, is similar to the Hindi Devanagari alphabet except for its use for certain words. Some words in Marathi preserve the schwa, which has been omitted in other languages which use Devanagari. For example, the word 'रंग' (colour) is pronounced as 'ranga' in Marathi & 'rang' in other languages using Devanagari, and 'खरं' (true), despite the anuswara, is pronounced as 'khara'. The anuswara in this case is used to avoid schwa deletion in pronunciation; most other languages using Devanagari show schwa deletion in pronunciation despite the presence of schwa in the written spelling. From the 13th century until the beginning of British rule in the 19th century, Marathi was written in the Modi script for administrative purposes but in Devanagari for literature. Since 1950 it has been written in the Balbodh style of Devanagari. Except for Father Thomas Stephens' Krista Purana in the Latin script in the 1600s, Marathi has mainly been printed in Devanagari because William Carey, the pioneer of printing in Indian languages, was only able to print in Devanagari. He later tried printing in Modi but by that time, Balbodh Devanagari had been accepted for printing.

Devanagari

Marathi is usually written in the Balbodh version of Devanagari script, an abugida consisting of 36 consonant letters and 16 initial-vowel letters. It is written from left to right. The Devanagari alphabet used to write Marathi is slightly different from the Devanagari alphabets of Hindi and other languages: there are additional letters in the Marathi alphabet and Western punctuation is used.

William Carey in 1807 Observed that as with other parts of India, a traditional duality existed in script usage between Devanagari for religious texts, and Modi for commerce and administration.

Although in the Mahratta country the Devanagari character is well known to men of education, yet a character is current among the men of business which is much smaller, and varies considerably in form from the Nagari, though the number and power of the letters nearly correspond.

Vowels

| Devanagari | Transliterated | IPA | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| अ | a | /ə/ | |

| आ | ā | /a(ː)/ | |

| इ | i | /i/ | |

| ई | ī | /i(ː)/ | |

| उ | u | /u/ | |

| ऊ | ū | /u(ː)/ | |

| ऋ | ṛ | /ru/ | |

| ए | e | /e/ | |

| ऐ | ai | /əi/ | |

| ओ | o | /o/ | |

| औ | au | /əu/ | |

| अं | aṃ | /əm/ | |

| अः | aḥ | /əɦə/ |

Consonants

| क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ka /kə/ |

kha /kʰə/ |

ga /ɡə/ |

gha /ɡʱə/ |

ṅa (/ŋə/) |

|

| च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | |

| ca, ċa /t͡ɕə/ or /t͡sə/ |

cha /t͡ɕʰə/ |

ja, j̈a /d͡ʑə/ or /d͡zə/ |

jha, j̈ha /d͡ʑʱə/ or /d͡zʱə/ |

ña (/ɲə/) |

|

| ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | |

| ṭa /ʈə/ |

ṭha /ʈʰə/ |

ḍa /ɖə/ |

ḍha /ɖʱə/ |

ṇa /ɳə/ |

|

| त | थ | द | ध | न | |

| ta /tə/ |

tha /tʰə/ |

da /də/ |

dha /dʱə/ |

na /nə/ |

|

| प | फ | ब | भ | म | |

| pa /pə/ |

pha /pʰə/ or /fə/ |

ba /bə/ |

bha /bʱə/ |

ma /mə/ |

|

| य | र | ल | व | श | |

| ya /jə/ |

ra /ɾə/ |

la /lə/ |

va /ʋə/ |

śa /ʃə/ |

|

| ष | स | ह | ळ | क्ष | ज्ञ |

| ṣa /ʂə/ |

sa /sə/ |

ha /ɦə/ |

ḷa /ɭə/ |

kṣa /kɕə/ |

jña /dɲə/ |

It is written from left to right. Devanagari used to write Marathi is slightly different from that of Hindi or other languages. It uses additional vowels and consonants that are not found in other languages that also use Devanagari.

Example of consonant–vowel combination

Combination of the vowels with K:

| Script | Pronunciation (IPA) |

|---|---|

| क | /kə/ |

| का | /kaː/ |

| कि | /ki/ |

| की | /kiː/ |

| कु | /ku/ |

| कू | /kuː/ |

| कृ | /kru/ |

| के | /ke/ |

| कै | /kəi̯/ |

| को | /ko/ |

| कौ | /kəu̯/ |

| कं | /kəm/ |

| कः | /kəɦ(ə)/ |

The Modi alphabet

See also: Modi alphabetFrom the thirteenth century until 1950, Marathi, especially for business use, was written in the Modi alphabet, a cursive script designed for minimising the lifting of pen from paper while writing.

Consonant clusters in Devanagari

In Devanagari, consonant letters by default come with an inherent schwa. Therefore, तयाचे will be 'təyāche', not 'tyāche'. To form 'tyāche', you will have to write it as त् + याचे, giving त्याचे.

When two or more consecutive consonants are followed by a vowel then a jodakshar (consonant cluster) is formed. Some examples of consonant clusters are shown below:

- त्याचे – tyāche – "his"

- प्रस्ताव – prastāva – "proposal"

- विद्या – vidyā – "knowledge"

- म्यान – myān – "Sheath/scabbard"

- त्वरा – tvarā – "immediate/Quick"

- महत्त्व – mahattva – "importance"

- फक्त – phakta – "only"

- बाहुल्या – bāhulyā – "dolls"

- कण्हेरी – kaṇherī – "oleander" (known for its flowers)

- न्हाणे – nhāṇe – "bathing"

- म्हणून – mhaṇūna – "therefore"

- तऱ्हा – taṟhā – "different way of behaving"

- कोल्हा – kolhā – "fox"

- केव्हा – kevhā – "when"

In writing, Marathi has a few digraphs that are rarely seen in the world's languages, including those denoting the so-called "nasal aspirates" (ṇh (ण्ह), nh (न्ह) and mh (म्ह)) and liquid aspirates (rh, ṟh, lh (ल्ह), and vh व्ह). Some examples are given above.

Eyelash reph/raphar

See also: Zero-width joiner and ViramaThe eyelash reph/raphar (रेफ/ रफार) (र्) exists in Marathi as well as Nepali. The eyelash reph/raphar (र्) is produced in Unicode by the sequence + + and + + . In Marathi, when 'र' is the first consonant of a consonant cluster and occurs at the beginning of a syllable, it is written as an eyelash reph/raphar.

| Examples |

|---|

| तर्हा |

| वाऱ्याचा |

| ऱ्हास |

| ऱ्हस्व |

| सुऱ्या |

| दोऱ्या |

Minimal pairs

Source:

| Using the (Simple) Reph/Raphar | Using the Eyelash Reph/Raphar |

|---|---|

| आचार्यास (to the teacher) | आचार्यास (to the cook) |

| दर्या (ocean) | दर्या (valleys) |

Braille

In February 2008, Swagat Thorat published India's first Braille newspaper, the Marathi Sparshdnyan, a news, politics and current affairs fort nightly magazine.

Grammar

Main article: Marathi grammarMarathi grammar shares similarities with other modern Indo-Aryan languages. Jain Acharya Hemachandra is the grammarian of Maharashtri Prakrit. The first modern book exclusively concerning Marathi grammar was printed in 1805 by William Carey.

Marathi employs agglutinative, inflectional and analytical forms. Unlike most other Indo-Aryan languages, Marathi has kept three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. The primary word order of Marathi is subject–object–verb Marathi follows a split-ergative pattern of verb agreement and case marking: it is ergative in constructions with either perfective transitive verbs or with the obligative ("should", "have to") and it is nominative elsewhere. An unusual feature of Marathi, as compared to other Indo-European languages, is that it displays inclusive and exclusive we, common to the Austroasiatic and Dravidian languages. Other similarities to Dravidian include the extensive use of participial constructions and also to a certain extent the use of the two anaphoric pronouns swətah and apəṇ. Numerous scholars have noted the existence of Dravidian linguistic patterns in the Marathi language.

Sharing of linguistic resources with other languages

Marathi is primarily influenced by Prakrit, Maharashtri, and Apabhraṃśa. Formal Marathi draws literary and technical vocabulary from Sanskrit. Marathi has also shared directions, vocabulary, and grammar with languages such as Indian Dravidian languages. Over a period of many centuries, the Marathi language and people have also come into contact with foreign languages such as Persian, Arabic, English, and European romance languages such as French, Spanish, Portuguese and other European languages.

Dravidian Influence

Spoken in the historically active region of the Deccan Plateau, the language has been subject to contact and mostly one-way influence with the surrounding Dravidian languages. Up to 5% of Marathi's basic vocabulary is of a Dravidian origin. According to various scholars like Bloch (1970) and Southworth (1971), Marathi's very origins can be traced to a pidgin or a substratum origin with surrounding Dravidian language.

Morphology and etymology

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Spoken Marathi contains a high number of Sanskrit-derived (tatsama) words. Such words are for example nantar (from nantara or after), pūrṇa (pūrṇa or complete, full, or full measure of something), ola (ola or damp), kāraṇ (kāraṇa or cause), puṣkaḷ (puṣkala or much, many), satat (satata or always), vichitra (vichitra or strange), svatah (svatah or himself/herself), prayatna (prayatna or effort, attempt), bhītī (from bhīti, or fear) and bhāṇḍe (bhāṇḍa or vessel for cooking or storing food). Other words ("tadbhavas") have undergone phonological changes from their Sanskrit roots, for example dār (dwāra or door), ghar (gṛha or house), vāgh (vyāghra or tiger), paḷaṇe (palāyate or to run away), kiti (kati or how many) have undergone more modification. Examples of words borrowed from other Indian and foreign languages include:

- Hawā: "air" directly borrowed from Arabic hawa

- Jamin: "land" borrowed from Persian zamin

- Kaydā: "law" borrowed from Arabic qaeda

- "Mahiti" : "information" borrowed from Arabic "Mahiyya"

- Jāhirāt: "advertisement" is derived from Arabic zaahiraat

- Marjī: "wish" is derived from Persian marzi

- Shiphāras: "recommendation" is derived from Persian sefaresh

- Hajērī: "attendance" from Urdu haziri

- Aṇṇā: "father", "grandfather" or "elder brother" borrowed from Dravidian languages

- Undir: "rat" borrowed from Munda languages

A lot of English words are commonly used in conversation and are considered to be assimilated into the Marathi vocabulary. These include words like "pen" (पेन, pen) and "shirt" (शर्ट, sharṭa) whose native Marathi counterparts are lekhaṇī (लेखणी) and sadarā (सदरा) respectively.

Compounds

Marathi uses many morphological processes to join words together, forming compounds. For example, ati + uttam gives the word atyuttam, Ganesh + Utsav = Ganeshotsav, miith-bhaakar ("salt-bread"), udyog-patii ("businessman"), ashṭa-bhujaa ("eight-hands", name of a Hindu goddess).

Counting

Like many other languages, Marathi uses distinct names for the numbers 1 to 20 and each multiple of 10, and composite ones for those greater than 20.

As with other Indic languages, there are distinct names for the fractions 1⁄4, 1⁄2, and 3⁄4. They are pāva, ardhā, and pāuṇa, respectively. For most fractions greater than 1, the prefixes savvā-, sāḍē-, pāvaṇe- are used. There are special names for 3⁄2 (dīḍ), 5⁄2 (aḍīch), and 7⁄2 (aut).

Powers of ten are denoted by separate specific words as depicted in the table below.

| Number power to 10 | Marathi Number name | In Devanagari |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Eka, Ekaka | एक/एकक |

| 10 | Daha, Dashaka | दहा/दशक |

| 10 | Shambhara, Shataka | शंभर/शतक |

| 10 | Hajara, Sahasra, | हजार/सहस्र |

| 10 | Dasha Hajara, Dasha Sahasra | दशहजार/दशसहस्र |

| 10 | Lakha, Laksha | लाख/लक्ष |

| 10 | Daha Lakha, Dasha Laksha | दहा लाख (दशलक्ष) |

| 10 | Koti | कोटी |

| 10 | Dasha Koti | दशकोटी |

| 10 | Abja, Arbuda | अब्ज/अर्बुद |

| 10 | Dasha-Abja | दशाब्ज |

| 10 | Vrunda | वृंद |

| 10 | Kharva (Kharab) | खर्व |

| 10 | Nikharva | निखर्व |

| 10 | Sashastra | सशस्त्र |

| 10 | Mahapadma, Padma | महापद्म/पद्म |

| 10 | Kamala | कमळ |

| 10 | Shanku, Shankha | शंकू/शंक |

| 10 | Skanda | स्कंद |

| 10 | Suvachya | सुवाच्य |

| 10 | Jaladhi, Samudra | जलधी/समुद्र |

| 10 | Krutya | कृत्य |

| 10 | Antya | अंत्य |

| 10 | Ajanma | आजन्म |

| 10 | Madhya | मध्य |

| 10 | Lakshmi | लक्ष्मी |

| 10 | Parardha | परार्ध |

A positive integer is read by breaking it up from the tens digit leftwards, into parts each containing two digits, the only exception being the hundreds place containing only one digit instead of two. For example, 1,234,567 is written as 12,34,567 and read as 12 lakh 34 Hazara 5 she 67 (१२ लाख ३४ हजार ५ शे ६७).

Every two-digit number after 18 (11 to 18 are predefined) is read backward. For example, 21 is read एक-वीस (1-twenty). Also, a two digit number that ends with a 9 is considered to be the next tens place minus one. For example, 29 is एकोणतीस (एक-उणे-तीस) (thirty minus one). Two digit numbers used before Hazara are written in the same way.

Marathi on computers and the Internet

Shrilipee, Shivaji, kothare 2,4,6, Kiran fonts KF-Kiran and many more (about 48) are clip fonts that were used prior to the introduction of Unicode standard for Devanagari script. Clip fonts are in vogue on PCs even today since most computers use English keyboards. Even today a large number of printed publications such as books, newspapers and magazines are prepared using these ASCII based fonts. However, clip fonts cannot be used on internet since those did not have Unicode compatibility.

Earlier Marathi suffered from weak support by computer operating systems and Internet services, as have other Indian languages. But recently, with the introduction of language localisation projects and new technologies, various software and Internet applications have been introduced. Marathi typing software is widely used and display interface packages are now available on Windows, Linux and macOS. Many Marathi websites, including Marathi newspapers, have become popular especially with Maharashtrians outside India. Online projects such as the Marathi language Misplaced Pages, with 76,000+ articles, the Marathi blogroll, and Marathi blogs have gained immense popularity.

Natural language processing for Marathi

More recent attention has focused on developing natural language processing tools for Marathi. Some studies proposed a couple of text corpora for Marathi. L3CubeMahaSent is the first major publicly available Marathi dataset for sentiment analysis. It contains about 16,000 distinct tweets classified into three broad classes, such as positive, negative, and neutral. L3Cube-MahaNER is a dataset for named-entity recognition consisting of 25,000 manually tagged sentences categorised according to the eight entity classes. There are at least two public available datasets for hate speech detection in Marathi: L3Cube-MahaHate and HASOC2021.

The HASOC2021 dataset was proposed for conducting a machine learning competition on hate, offensive, and profane content identification in Marathi collocated with Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation (FIRE 2021). The participants of the competition presented 25 solutions based on supervised learning. The winning teams used pre-trained language models (XLM-RoBERTa, Language Agnostic BERT Sentence Embeddings (LaBSE)) fine-tuned on the HASOC2021 dataset proposed by the organisers. The participants also experimented with the joint use of multilingual data for fine-tuning. To read more detailed about NLP in marathi read this article.

Corpus Development in Marathi

Text Corpus and Corpus Linguistics show how texts, sentences, or words from written or spoken language have changed over time or how they have been used in an organised way. The Volume VII: 'Indo-Aryan Languages (Southern Group) of the 'Linguistic Survey of India' by George Abraham Grierson describes first systematic and structured attempt to create documentation of Marathi language data.

Corpora in Marathi

Attempts have been made to create Corpus of Marathi. One of the first efforts to make a corpus with Indian text was the Kolhapur Corpus of Indian English (Shastri, 1986). The corpus was developed at the University in Maharastra, but Indian English was studied. The IIT Bombay WordNet (IndoWordNet; Bhattacharya, 2010) project in Indian languages includes Marathi. WordNet do not give word counts for further useful data analysis. The raw text based corpus in Marathi (Ramamoorthy et al., 2019a) is based on sampled pages from different select books. This work is carried out at Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore. A corpus-based linguistic study at the University of Mumbai explores the language contact between English and Marathi by compiling and analysing an over-arching corpus of English loan-words in Marathi existing between the years 2001 and 2020. The study also investigates the attitudes of Marathi speakers towards English loan-words in contemporary Marathi, attempting to understand their motivations for borrowing English words (Doibale, 2022).

The work at University of Mumbai by Belhekar and Bhargava (2023) provided the first Marathi word count collection (Marathi WordCorp). The bag-of-words (BoW) model was used to make 1-gram (single-word) Marathi WordCorp. They used more than 700 complete works of literature.

The Google Books Ngram Viewer (Michel et al., 2011) is a relatively new and advanced method that shows how the frequency of n-grams has changed over a specific period. There is no database of Indian languages in the Google Books Ngram viewer. The Indian Languages Word Corpus (ILWC) WebApp, which was made by Belhekar and Bhargava, shows how often words are used by decade from before 1920 to 2020. The limitation with the method is that it only gives researchers the raw OCR data to "combine and collapse frequencies of correctly and incorrectly recognised words" (p. 2).

Statistical Models for Marathi Corpora

Attempts to evaluate statistical models for Marathi language Corpuses and text-collections have been carried out. For the Marathi corpus (Marathi WordCorp), the y-intercept of Zipf's law is reported as 12.49, and the coefficient is 0.89 and these numbers show that Zipf's law is applicable for Marathi language. The coefficients show that the number of words and texts used in the corpus metadata is enough. Heaps' law intercept for the Marathi word corpora is 2.48, and the coefficient is 0.73. The coefficient values show that there are more unique words in Marathi writings than would be expected. The higher number of unique words could be due to the number of alphabets (36 consonant letters and 16 initial-vowel letters, with each consonant taking 14 forms with vowel pairs), the orthographic features of the Devanagari script (for example, the same word can be written in different ways), the use of consonant clusters (jodakshar), the number of suffixes a word can have, etc.

Marathi Language Day

Marathi Language Day (मराठी दिन/मराठी दिवस transl. Marathi Din/Marathi Diwas is celebrated on 27 February every year across the Indian states of Maharashtra and Goa. This day is regulated by the Ministry of Marathi Language. It is celebrated on the Birthday of eminent Marathi Poet V.V. Shirwadkar, popularly known as Kusumagraj.

Essay competitions and seminars are arranged in schools and colleges, and government officials are asked to conduct various events.

See also

References

- ^ Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue". censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Indian Linguistics. Linguistic Society of India. 2008. p. 161.

- ^ Modern Marathi at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Old Marathi at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Dhoṅgaḍe, Rameśa; Wali, Kashi (2009). "Marathi". London Oriental and African Language Library. 13. John Benjamins Publishing Company: 101, 139. ISBN 9789027238139.

- ^ "झाडी बोली (मराठी भाषेतील सौंदर्यस्थळे) | मिसळपाव". www.misalpav.com. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Marathi | South Asian Languages and Civilizations". salc.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Ghatage. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGhatage (help)

- "Know Your City: The Modi script, using which Maratha empire would conduct business". 5 February 2022.

- "'Other' Modi wave: How 700-year Marathi script is making a comeback". The Times of India. 7 July 2019.

- ^ "The Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act, 1987" (PDF). indiacode.nic.in. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ The Goa, Daman, and Diu Official Language Act, 1987 makes Konkani the official language but provides that Marathi may also be used "for all or any of the official purposes". The Government also has a policy of replying in Marathi to correspondence received in Marathi. Commissioner Linguistic Minorities, , pp. para 11.3 Archived 19 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- Lal, M. B. (2008). N. E. R. Exam. Upkar Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7482-464-6.

- Kaminsky, Arnold P.; Roger, D. Long PH D. (23 September 2011). India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic [2 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-37463-0.

- ^ "Abstract of Language Strength in India: 2011 Census" (PDF). Censusindia.gov.in.

- "arts, South Asian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite.

- ^ Kumar, Vivek; Roy, Suryagni (3 October 2024). "Marathi, Pali, Prakrit, Assamese, Bengali now among classical languages". India Today. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- Dhongde & Wali 2009, pp. 11–15.

- Pandharipande, Rajeshwari (1997). Marathi. Routledge. p. xxxvii. ISBN 0-415-00319-9.

- Bloch 1970, p. 32.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 384. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- D'Arms, John H.; Thurnau, Arthur F.; Alcock, Susan E. (9 August 2001). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-521-77020-0.

- Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1974). Some Early Dynasties of South India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-81-208-2941-1.

- Clara Lewis (16 April 2018). "Clamour grows for Marathi to be given classical language status". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 53.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, pp. 53–54.

- Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 54.

- Cynthia Talbot (20 September 2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-0-19-803123-9.

- Mokashi 1987, p. 39.

- Doderet, W. (1926). "The Passive Voice of the Jnanesvari". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 4 (1): 59–64. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 607401.

- Kher 1895, pp. 446–454.

- Keune, Jon Milton (2011). Eknāth Remembered and Reformed: Bhakti, Brahmans, and Untouchables in Marathi Historiography (Thesis). New York, New York, US: Columbia University press. p. 32. doi:10.7916/D8CN79VK. hdl:10022/AC:P:11409. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Natarajan, Nalini, ed. (1996). Handbook of twentieth century literatures of India (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0313287787.

- eGangotri. Param Rahasya By Shri Manmath Swami Shaiva Bharati Varanasi.

- Kulkarni, G.T. (1992). "Deccan (Maharashtra) Under the Muslim Rulers From Khaljis to Shivaji : a Study in Interaction, Professor S.M Katre Felicitation". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 51/52: 501–510. JSTOR 42930434.

- ^ Qasemi, S. H. "Marathi Language, Persian Elements In". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- Pathan, Y. M. (2006). Farsi-Marathi Anubandh (फारसी मराठी अनुबंध) (PDF). Mumbai: महाराष्ट्र राज्य साहित्य आणि संस्कृती मंडळ. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Gordon, Stewart (1993). Cambridge History of India: The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- Kamat, Jyotsna. "The Adil Shahi Kingdom (1510 CE to 1686 CE)". Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-521-25484-1. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Pollock, Sheldon (14 March 2011). Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500–1800. Duke University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8223-4904-4.

- Pollock, Sheldon (14 March 2011). Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500–1800. Duke University Press. pp. 50, 60. ISBN 978-0-8223-4904-4.

- Callewaert, Winand M.; Snell, Rupert; Tulpule, S G (1994). According to Tradition: Hagiographical Writing in India. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 166. ISBN 3-447-03524-2. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ Ranade, Ashok D. (2000). Kosambi, Meera (ed.). Intersections : socio-cultural trends in Maharashtra. London: Sangam. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-0863118241.

- Sawant, Sunil (2008). Ray, Mohit K. (ed.). Studies in translation (2nd rev. and enl. ed.). New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9788126909223.

- Molesworth, James; Candy, Thomas (1857). Molesworth's, Marathi-English dictionary. Narayan G Kalelkar (preface) (2nd ed.). Pune: J.C. Furla, Shubhada Saraswat Prakashan. ISBN 81-86411-57-7.

- Chavan, Dilip (2013). Language politics under colonialism : caste, class and language pedagogy in western India. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. p. 174. ISBN 978-1443842501.

- Chavan, Dilip (2013). Language politics under colonialism : caste, class and language pedagogy in western India (first ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. pp. 136–184. ISBN 978-1443842501. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Deo, Shripad D. (1996). Natarajan, Nalini (ed.). Handbook of twentieth century literatures of India (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0313287787.

- Rajyashree (1994). Goparaju Sambasiva Rao (ed.). Language Change: Lexical Diffusion and Literacy. Academic Foundation. pp. 45–58. ISBN 978-81-7188-057-7.

- Smith, George (2016). Life of William Carey: Shoemaker and Missionary. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 258. ISBN 978-1536976120.

- Tucker, R., 1976. Hindu Traditionalism and Nationalist Ideologies in Nineteenth-Century Maharashtra. Modern Asian Studies, 10(3), pp.321-348.

- Govind, Ranjani (29 May 2019). "Musical drama brings epic to life". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Rosalind O'Hanlon (22 August 2002). Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and Low Caste Protest in Nineteenth-Century Western India. Cambridge University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-521-52308-0.

- Rao, P.V. (2008). "Women's Education and the Nationalist Response in Western India: Part II–Higher Education". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 15 (1): 141–148. doi:10.1177/097152150701500108. S2CID 143961063.

- Rao, P.V. (2007). "Women's Education and the Nationalist Response in Western India: Part I-Basic Education". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 14 (2): 307. doi:10.1177/097152150701400206. S2CID 197651677.

- Gail Omvedt (1974). "Non-Brahmans and Nationalists in Poona". Economic and Political Weekly. 9 (6/8): 201–219. JSTOR 4363419.

- Deo, Shripad D. (1996). Natarajan, Nalini (ed.). Handbook of twentieth century literatures of India (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0313287787.

- Pardeshi, Prashant (2000). The Passive and Related Constructions in Marathi (PDF). Kobe papers in linguistics. Kobe, Japan: Kobe University. pp. 123–146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2018.

- Deshpande, G. P. (1997). "Marathi Literature since Independence: Some Pleasures and Displeasures". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (44/45): 2885–2892. JSTOR 4406042.

- "अवलिया लोकसाहित्यीक", "Sakal, a leading Marathi Daily", Pune, 21 November 2021.

- Natarajan, Nalini; Emmanuel Sampath Nelson (1996). "Chap 13: Dalit Literature in Marathi by Veena Deo". Handbook of twentieth-century literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 363. ISBN 0-313-28778-3.

- Issues of Language and Representation: Babu Rao Bagul Handbook of twentieth-century literatures of India, Editors: Nalini Natarajan, Emmanuel Sampath Nelson. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996. ISBN 0-313-28778-3. Page 368.

- Mother 1970 Indian short stories, 1900–2000, by E.V. Ramakrishnan, I. V. Ramakrishnana. Sahitya Akademi. Page 217, Page 409 (Biography).

- Jevha Mi Jat Chorali Hoti (1963) Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2. Editors Amaresh Datta. Sahitya Akademi, 1988. ISBN 81-260-1194-7. Page 1823.

- "Of art, identity, and politics". The Hindu. 23 January 2003. Archived from the original on 2 July 2003.

- Mathur, Barkha (28 March 2018). "City hails Pantawane as 'father of Dalit literature'". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Deo, Veena; Zelliot, Eleanor (1994). "Dalit Literaturetwenty-Five Years of Protest? Of Progress?". Journal of South Asian Literature. 29 (2): 41–67. JSTOR 25797513.

- Feldhaus, Anne (1996). Images of Women in Maharashtrian Literature and Religion. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780791428375. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Maya Pandit (27 December 2017). "How three generations of Dalit women writers saw their identities and struggle?". The Indian Express. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Assayag, Jackie; Fuller, Christopher John (2005). Globalizing India: Perspectives from Below. London, UK: Anthem Press. p. 80. ISBN 1-84331-194-1.

- ^ "Marathi". ethnologue.com.

- "Marathi Culture, History and Heritage in Mauritius" (PDF). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Summary by language size". Ethnologue. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2019. For items below #26, see individual Ethnologue entry for each language.

- "Marathi". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "Schedule". constitution.org.

- "Marathi may become the sixth classical language". Indian Express. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- "Dept. of Marathi, M.S. University of Baroda". Msubaroda.ac.in. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "University College of Arts and Social Sciences". osmania.ac.in.

- kudadmin. "Departments and Faculty". kudacademics.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- "Department of P.G. Studies and Research in Marathi". kar.nic.in.

- "Devi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya, Indore". www.dauniv.ac.in. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Dept.of Marathi, Goa University". Unigoa.ac.in. 27 April 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "01 May 1960..." www.unitedstatesofindia.com.

- "मराठी भाषा दिवस - २७ फेब्रुवारी". www.marathimati.com.

- Khodade, 2004

- Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (25 September 2017). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-039324-8.

- देसाई, बापूराव (2006). महाराष्ट्रातील समग्र बोलींचे: लोकसाहित्यशास्त्रीय अध्ययन : महाराष्ट्रातूनच नव्हे तर भारतातून प्रथमतः एकाच ग्रंथात सर्व बोलींचे लोकसाहित्यशास्त्र संस्कृतीदर्शन (in Marathi). अनघा प्रकाशन. p. 79.

- Dhongde & Wali 2009.

- Sardesai, p. 547.

- Ghatage, p. 111.

- ^ *Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2

- Pandharipande, Rajeshwari V. (2003). Marathi. George Cardona and Dhanesh Jain (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages: London & New York: Routledge. pp. 789–790.

- In Kudali dialect

- Masica (1991:97)

- Sohoni, Pushkar (May 2017). "Marathi of a single type: the demise of the Modi script". Modern Asian Studies. 51 (3): 662–685. doi:10.1017/S0026749X15000542. S2CID 148081127.

- Rao, Goparaju Sambasiva (1994). Language Change: Lexical Diffusion and Literacy. Delhi: Academic Foundation. p. 49. ISBN 81-7188-057-6.

- Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indian Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 437. ISBN 9780521299442. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014.

- Rao, Goparaju Sambasiva (1994). Language Change: Lexical Diffusion and Literacy. Academic Foundation. pp. 48 and 49. ISBN 9788171880577. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014.

- Ajmire, P.E.; Dharaskar, RV; Thakare, V M (22 March 2013). "A Comparative Study of Handwritten Marathi Character Recognition" (PDF). International Journal of Computer Applications. Introduction. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014.

- Bhimraoji, Rajendra (28 February 2014). "Reviving the Modi Script" (PDF). Typoday. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014.

- Carey, William. "Memoir Relative to the Translations" 1807: Serampore Mission Press.

- Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Indic Working Group (7 November 2004). "Devanagari Eyelash Ra". The Unicode Consortium. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014.

- Kalyan, Kale; Soman, Anjali (1986). Learning Marathi. Pune: Shri Vishakha Prakashan. p. 26.

- Naik, B.S. (1971). Typography of Devanagari-1. Bombay: Directorate of Languages.

- Menon, Sudha (15 January 2008). "Marathi magazine to be launched in Feb is first Braille fortnightly". mint. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Bhosale, G.; Kembhavi, S.; Amberkar, A.; Mhatre, M.; Popale, L.; Bhattacharyya, P. (2011), "Processing of Kridanta (Participle) in Marathi" (PDF), Proceedings of ICON-2011: 9th International Conference on Natural Language Processing, Macmillan Publishers, India

- "Wals.info". Wals.info. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Dhongde & Wali 2009, pp. 179–80.

- Dhongde & Wali 2009, p. 263.

- Polomé, Edgar C. (1 January 1992). Reconstructing Languages and Cultures. Walter De Gruyter. p. 521. ISBN 9783110867923.

- ^ J. Bloch (1970). Formation of the Marathi Language. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 33, 180. ISBN 978-81-208-2322-8.

- Southworth, Franklin (2005). "Prehistoric Implications of the Dravidian element in the NIA lexicon, with special attention to Marathi" (PDF). IJDL. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics.

- Southworth, F. C. (1971). Detecting prior creolization: an analysis of the historical origins of Marathi Franklin C. Southworth; In: Hymes, Dell, Pidginization and creolization of languages : proceedings of a conference held at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica, April 1968.

- "The formation of the Marathi language, by Jules Bloch. Translated by Dev Raj Chanana - Catalogue | National Library of Australia". catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- "Indian Numbering System". Oocities.org. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Sushma Gupta. "Indian Numbering System". Sushmajee.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- "Welcome to www.kiranfont.com". Kiranfont.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Askari, Faiz. "Inside the Indian Blogosphere". Express Computer. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- Kulkarni, Atharva; Mandhane, Meet; Likhitkar, Manali; Kshirsagar, Gayatri; Joshi, Raviraj (2021). L3CubeMahaSent: A Marathi Tweet-based Sentiment Analysis Dataset (PDF). Proceedings of the Eleventh Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis. Online. pp. 213–220.

- Patil, Parth; Ranade, Aparna; Sabane, Maithili; Litake, Onkar; Joshi, Raviraj (12 April 2022). "L3Cube-MahaNER: A Marathi Named Entity Recognition Dataset and BERT models". arXiv:2204.06029 .

- Velankar, Abhishek; Patil, Hrushikes; Gore, Amol; Salunke, Shubham; Joshi, Raviraj (22 May 2022). "L3Cube-MahaHate: A Tweet-based Marathi Hate Speech Detection Dataset and BERT models". arXiv:2203.13778 .

- Modha, Sandip; Mandl, Thomas; Shahi, Gautam Kishore; Madhu, Hiren; Satapara, Shrey; Ranasinghe, Tharindu; Zampieri, Marcos (2021). Overview of the HASOC subtrack at FIRE 2021: Hate speech and offensive content identification in English and Indo-Aryan languages and conversational hate speech. Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation. Online. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1145/3503162.3503176. hdl:2436/624705.

- Nene, Mayuresh; North, Kai; Ranasinghe, Tharindu; Zampieri, Marcos (2021). Transformer Models for Offensive Language Identification in Marathi. Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation (Working Notes) (FIRE). Online. pp. 272–281.

- Glazkova, Anna; Kadantsev, Michael; Glazkov, Maksim (2021). Fine-tuning of Pre-trained Transformers for Hate, Offensive, and Profane Content Detection in English and Marathi. Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation (Working Notes) (FIRE). Online. pp. 52–62. arXiv:2110.12687.

- Shastri, S.V. (1986). "The Kolhapur Corpus of Indian English".

- Bhattacharyya, Pushpak (2010). IndoWordNet. (in Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation LREC'10). Valletta, Malta: European Language Resources Association (ELRA). pp. 3785–3792. ISBN 978-2-9517408-6-0.

- "A Gold Standard Marathi Raw Text Corpus". data.ldcil.org. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- Doibale, Kranti (2022). "A Corpus-Based Linguistic Study of English Loan-Words in Contemporary Marathi". hdl:10603/487393. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Belhekar, Vivek; Bhargava, Radhika (December 2023). "Development of word count data corpus for Hindi and Marathi literature". Applied Corpus Linguistics. 3 (3): 100070. doi:10.1016/j.acorp.2023.100070. S2CID 261150616.

- Michel, Jean-Baptiste; Shen, Yuan Kui; Aiden, Aviva Presser; Veres, Adrian; Gray, Matthew K.; The Google Books Team; Pickett, Joseph P.; Hoiberg, Dale; Clancy, Dan; Norvig, Peter; Orwant, Jon; Pinker, Steven; Nowak, Martin A.; Aiden, Erez Lieberman (14 January 2011). "Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books". Science. 331 (6014): 176–182. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..176M. doi:10.1126/science.1199644. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 3279742. PMID 21163965.

- "Indian Languages Word Corpus". indianlangwordcorp.shinyapps.io. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- "मराठी भाषा दिवस - २७ फेब्रुवारी". MarathiMati.com. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "jagatik Marathi bhasha din celebration - divyamarathi.bhaskar.com". divyabhaskar. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "आम्ही मराठीचे शिलेदार!". Loksatta. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Bibliography

- Bloch, J (1970). Formation of the Marathi Language. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2322-8.

- Ghatage, A.M (1970). Marathi Of Kasargod. Mumbai.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dhongde, Ramesh Vaman; Wali, Kashi (2009). Marathi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. ISBN 978-90-272-38139.

- A Survey of Marathi Dialects. VIII. Gāwḍi, A. M. Ghatage & P. P. Karapurkar. The State Board for Literature and Culture, Bombay. 1972.

- Marathi: The Language and its Linguistic Traditions - Prabhakar Machwe, Indian and Foreign Review, 15 March 1985.

- 'Atyavashyak Marathi Vyakaran' (Essential Marathi Grammar) - Dr. V. L. Vardhe

- 'Marathi Vyakaran' (Marathi Grammar) - Moreshvar Sakharam More.

- 'Marathi Vishwakosh, Khand 12 (Marathi World Encyclopedia, Volume 12), Maharashtra Rajya Vishwakosh Nirmiti Mandal, Mumbai

- 'Marathyancha Itihaas' by Dr. Kolarkar, Shrimangesh Publishers, Nagpur

- 'History of Medieval Hindu India from 600 CE to 1200 CE, by C. V. Vaidya

- Marathi Sahitya (Review of the Marathi Literature up to I960) by Kusumavati Deshpande, Maharashtra Information Centre, New Delhi

- Christian Lee Novetzke (2016). The Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54241-8.

- Kher, Appaji Kashinath (1895), A higher Anglo-Marathi grammar, pp. 446–454

- Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna (1987), Palkhi: An Indian Pilgrimage, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-461-6

External links

- Dictionaries

- Molesworth, J. T. (James Thomas). A dictionary, Marathi, and English. 2d ed., rev. and all. Bombay: Printed for government at the Bombay Education Society's press, 1857.

- Vaze, Shridhar Ganesh. The Aryabhusan school dictionary, Marathi-English. Poona: Arya-Bhushan Press, 1911.

- Tulpule, Shankar Gopal and Anne Feldhaus. A dictionary of old Marathi. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, 1999.

| Marathi | |

|---|---|

| Marathi dialects and Marathic languages | |

| Marathi scripts | |

| Other | |

| Arts | |

| Topics | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | |||||||||||||

| Divisions and Districts |

| ||||||||||||

| Million-plus cities in Maharashtra | |||||||||||||

| Other cities with municipal corporations | |||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| Portal:India | |||||||||||||

| Languages of India | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official languages |

| ||||||||||

| Major unofficial languages |

| ||||||||||

| Indo-Aryan languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dardic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northwestern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto- languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unclassified |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pidgins and creoles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Marathi language

- Languages attested from the 7th century

- Culture of Maharashtra

- Official languages of India

- Classical Language in India

- Languages written in Devanagari

- Southern Indo-Aryan languages

- Subject–object–verb languages

- Indo-Aryan languages

- Languages of Maharashtra

- Languages of Madhya Pradesh

- Languages of Karnataka

- Languages of Gujarat

- Languages written in Brahmic scripts