| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Perfume" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Perfume (UK: /ˈpɜːfjuːm/, US: /pərˈfjuːm/ ) is a mixture of fragrant essential oils or aroma compounds (fragrances), fixatives and solvents, usually in liquid form, used to give the human body, animals, food, objects, and living-spaces an agreeable scent. Perfumes can be defined as substances that emit and diffuse a pleasant and fragrant odor. They consist of manmade mixtures of aromatic chemicals and essential oils. The 1939 Nobel Laureate for Chemistry, Leopold Ružička stated in 1945 that "right from the earliest days of scientific chemistry up to the present time, perfumes have substantially contributed to the development of organic chemistry as regards methods, systematic classification, and theory."

Ancient texts and archaeological excavations show the use of perfumes in some of the earliest human civilizations. Modern perfumery began in the late 19th century with the commercial synthesis of aroma compounds such as vanillin or coumarin, which allowed for the composition of perfumes with smells previously unattainable solely from natural aromatics.

History

Main article: History of perfume

The word perfume is derived from the Latin perfumare, meaning "to smoke through". Perfumery, as the art of making perfumes, began in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley civilization and possibly Ancient China. It was further refined by the Romans and the Muslims.

One of the world's first-recorded chemists is considered to be a woman named Tapputi, a perfume maker mentioned in a cuneiform tablet from the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamia. She distilled flowers, oil, and calamus with other aromatics, then filtered and put them back in the still several times.

On the Indian subcontinent, perfume and perfumery existed in the Indus civilization (3300 BC – 1300 BC).

In 2003, archaeologists uncovered what are believed to be the world's oldest surviving perfumes in Pyrgos, Cyprus. The perfumes dated back more than 4,000 years. They were discovered in an ancient perfumery, a 300-square-meter (3,230 sq ft) factory housing at least 60 stills, mixing bowls, funnels, and perfume bottles. In ancient times people used herbs and spices, such as almond, coriander, myrtle, conifer resin, and bergamot, as well as flowers. In May 2018, an ancient perfume "Rodo" (Rose) was recreated for the Greek National Archaeological Museum's anniversary show "Countless Aspects of Beauty", allowing visitors to approach antiquity through their olfaction receptors. Romans and Greek extracted perfumes from diverse sources such as flowers, woods, seeds, roots, saps, gums. A temple to Athena in Elis, near Olympia, was said to have saffron blended into its wall plaster, allowing the interior to remain fragrant for 500 years.

In the 9th century the Arab chemist Al-Kindi (Alkindus) wrote the Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations, which contained more than a hundred recipes for fragrant oils, salves, aromatic waters, and substitutes or imitations of costly drugs. The book also described 107 methods and recipes for perfume-making and perfume-making equipment, such as the alembic (which still bears its Arabic name. described by Synesius in the 4th century).

The Persian chemist Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna) introduced the process of extracting oils from flowers by means of distillation, the procedure most commonly used today. He first experimented with the rose. Until his discovery, liquid perfumes consisted of mixtures of oil and crushed herbs or petals, which made a strong blend. Rose water was more delicate, and immediately became popular. Both the raw ingredients and the distillation technology significantly influenced western perfumery and scientific developments, particularly chemistry.

There is a controversy on whether perfumery was completely lost in Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. That said, the art of perfumery in Western Europe was reinvigorated after the Islamic invasion of Spain and Southern Italy in 711 and 827. The Islamic controlled cities of Spain (Al-Andalus) became major producers of perfumes that were traded throughout the Old World. Like in the ancient world, Andalusians used fragrance in devotion to God. Perfumes added a layer of cleanliness that was needed for their devotion. Andalusian women were also offered greater freedoms than women in other Muslim controlled regions and were allowed to leave their homes and socialize outside. This freedom allowed courtship to occur outside of the home. As a result, Andalusian women used perfumes for courtship.

Recipes of perfumes from the monks of Santa Maria Delle Vigne or Santa Maria Novella of Florence, Italy, were recorded from 1221. In the east, the Hungarians produced around 1370 a perfume made of scented oils blended in an alcohol solution – best known as Hungary Water – at the behest of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary. The art of perfumery prospered in Renaissance Italy, and in the 16th century the personal perfumer to Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589), René the Florentine (Renato il fiorentino), took Italian refinements to France. His laboratory was connected with her apartments by a secret passageway, so that no formulae could be stolen en route. Thanks to Rene, France quickly became one of the European centers of perfume and cosmetics manufacture. Cultivation of flowers for their perfume essence, which had begun in the 14th century, grew into a major industry in the south of France.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, perfumes were used primarily by the wealthy to mask body odors resulting from infrequent bathing. In 1693, Italian barber Giovanni Paolo Feminis created a perfume water called Aqua Admirabilis, today best known as eau de cologne; his nephew Johann Maria Farina (Giovanni Maria Farina) took over the business in 1732.

By the 18th century the Grasse region of France, Sicily, and Calabria (in Italy) were growing aromatic plants to provide the growing perfume industry with raw materials. Even today, Italy and France remain the center of European perfume design and trade.

-

Ancient Egyptian perfume vase in shape of an amphoriskos; 664–630 BC; glass: 8 cm × 4 cm (3.1 in × 1.6 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Ancient Egyptian perfume vase in shape of an amphoriskos; 664–630 BC; glass: 8 cm × 4 cm (3.1 in × 1.6 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Ancient Greek perfume bottle in shape of an athlete binding a victory ribbon around his head; circa 540s BC; Ancient Agora Museum (Athens)

Ancient Greek perfume bottle in shape of an athlete binding a victory ribbon around his head; circa 540s BC; Ancient Agora Museum (Athens)

-

Etruscan perfume vase, which is inscribed the word "suthina" ("for the tomb"); early 2nd century BC; bronze; height: 16 cm (6.3 in); Louvre

Etruscan perfume vase, which is inscribed the word "suthina" ("for the tomb"); early 2nd century BC; bronze; height: 16 cm (6.3 in); Louvre

-

Late Hellenistic glass gold-band mosaic alabastron (perfume bottle); 1st century BC; glass and gold leaf; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Late Hellenistic glass gold-band mosaic alabastron (perfume bottle); 1st century BC; glass and gold leaf; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Roman perfume bottle; 1st century AD; glass; 5.2 cm × 3.8 cm (2.0 in × 1.5 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Roman perfume bottle; 1st century AD; glass; 5.2 cm × 3.8 cm (2.0 in × 1.5 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Partially broken perfume amphora; 2nd century AD; glass; from Ephesus; Ephesus Archaeological Museum (Selçuk, Turkey)

Partially broken perfume amphora; 2nd century AD; glass; from Ephesus; Ephesus Archaeological Museum (Selçuk, Turkey)

-

British Rococo perfume vase; circa 1761; soft-paste porcelain; overall: 43.2 cm × 29.2 cm × 17.8 cm (17.0 in × 11.5 in × 7.0 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

British Rococo perfume vase; circa 1761; soft-paste porcelain; overall: 43.2 cm × 29.2 cm × 17.8 cm (17.0 in × 11.5 in × 7.0 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

British Neoclassical pair of perfume burners; probably circa 1770; derbyshire spar, tortoiseshell, and wood, Carrara marble base, gilded brass mounts, gilded copper liner; 33 cm × 14.3 cm × 14.3 cm (13.0 in × 5.6 in × 5.6 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

British Neoclassical pair of perfume burners; probably circa 1770; derbyshire spar, tortoiseshell, and wood, Carrara marble base, gilded brass mounts, gilded copper liner; 33 cm × 14.3 cm × 14.3 cm (13.0 in × 5.6 in × 5.6 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Art Nouveau perfume bottle; circa 1900; glass with gilt metal cover; overall: 13.4 cm (5.3 in); Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

Art Nouveau perfume bottle; circa 1900; glass with gilt metal cover; overall: 13.4 cm (5.3 in); Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

Dilution classes and terminologies

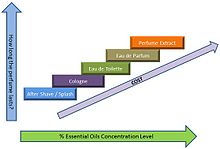

Perfume types reflect the concentration of aromatic compounds in a solvent, which in fine fragrance is typically ethanol or a mix of water and ethanol. Various sources differ considerably in the definitions of perfume types. The intensity and longevity of a fragrance is based on the concentration, intensity, and longevity of the aromatic compounds, or perfume oils, used. As the percentage of aromatic compounds increases, so does the intensity and longevity of the scent. Specific terms are used to describe a fragrance's approximate concentration by the percent of perfume oil in the volume of the final product. The most widespread terms are:

- Parfum or Extrait (P): 15–40% aromatic compounds (IFRA: typically ~20%). In English, parfum is also known as perfume extract, pure perfume, or simply perfume.

- Esprit de parfum (ESdP): 15–30% aromatic compounds, a seldom used strength concentration between EdP and parfum.

- Eau de parfum (EdP) or Parfum de toilette (PdT): 10–20% aromatic compounds (typically ~15%). It is sometimes called "eau de perfume" or "millésime." Parfum de toilette is a less common term, most popular in the 1980s, that is generally analogous to eau de parfum.

- Eau de toilette (EdT): 5–15% aromatic compounds (typically ~10%). This is the staple for most masculine perfumes.

- Eau de cologne (EdC): 3–8% aromatic compounds (typically ~5%). This concentration is often simply called cologne.

- Eau fraîche: 3% or less aromatic compounds. This general term encompasses products sold as "splashes," "mists," "veils" and other imprecise terms. Such products may be diluted with water rather than oil or alcohol.

Imprecise terminology

The wide range in the percentages of aromatic compounds that may be present in each concentration means that the terminology of extrait, EdP, EdT, and EdC is quite imprecise with regard to oil concentration. Although an EdP will often be more concentrated than an EdT and in turn an EdC, this is not always the case. Different perfumeries or perfume houses assign different amounts of oils to each of their perfumes. Therefore, although the oil concentration of a perfume in EdP dilution will necessarily be higher than the same perfume in EdT from within a company's same range, the actual amount will vary among companies. An EdT from one house may have a higher concentration of aromatic compounds than an EdP from another.

Furthermore, some fragrances with the same product name but having a different concentration may not only differ in their dilutions, but actually use different perfume oil mixtures altogether. For instance, in order to make the EdT version of a fragrance brighter and fresher than its EdP, the EdT oil may be "tweaked" to contain slightly more top notes or fewer base notes. Chanel No. 5 is a good example: its parfum, EdP, EdT, and now-discontinued EdC concentrations are in fact different compositions (the parfum dates to 1921, the EdT from the 1950s, and the EdP was not developed until the 1980s). In some cases, words such as extrême, intense, or concentrée that might indicate a higher aromatic concentration are actually completely different fragrances, related only because of a similar perfume accord. An example of this is Chanel's Pour Monsieur and Pour Monsieur concentrée. This complexity adds a layer of nuance to the understanding and appreciation of perfumery, where variations in concentration and formulation can significantly alter the olfactory ("the sense of smell") experience.

History of the terms and concentrations

The terms "perfume" and "cologne" lead to much confusion in English. "Perfume" is often used as a generic, overarching term to refer to fragrances marketed to women, regardless of their exact concentration. The term "cologne" is applied to those sold to men. The actual product worn by a woman may be an eau de parfum rather than an extrait, or by a man an eau de toilette rather than an eau de cologne. The reasons why the terms "perfume" and "cologne" are often used in a generic sense is related to the modern development of perfumery in Europe since the 18th century.

The term "cologne" was first used in Europe in the 18th century to refer to a family of fresh, citrus-based fragrances distilled using extracts from citrus, floral, and woody ingredients. These "classical colognes" were supposedly first developed in Cologne, Germany, hence the name. This type of cologne, which is still in production, describes unisex compositions "which are basically citrus blends and do not have a perfume parent." Examples include Mäurer & Wirtz's 4711 (created in 1799), and Guerlain's Eau de Cologne Impériale (1830). "Toilet water," or eau de toilette, referred to wide range of scented waters not otherwise known as colognes, and were popular throughout the 19th century.

The term "perfume" emerged in the late 19th century. The first fragrance labeled a "parfum" extract with a high concentration of aromatic compounds was Guerlain's Jicky in 1889. In the first half of the 20th century, fragrance companies began offering their products in more than one concentration, often pairing an extrait with a lighter eau de toilette suitable for day wear, which made their products available to a wider range of customers. As this process accelerated, perfume houses borrowed the term "cologne" to refer to an even more diluted interpretation of their fragrances than eau de toilette. Guerlain, for example, offered an eau de cologne version of its flagship perfume Shalimar and many of its other fragrances. In contrast to a classical eau de cologne, this type of modern cologne is a lighter, less concentrated interpretation of a more concentrated product, typically a pure parfum, and is usually the lightest concentration from a line of fragrance products.

The eau de parfum concentration and terminology is the most recent, being originally developed to offer the radiance of an EdT with the longevity of an extrait. Parfum de toilette and EdP began to appear in the 1970s and gained popularity in the 1980s. In the 21st century, EdP is probably the most widespread strength concentration. It is often the first concentration offered when a new fragrance is launched, and usually referred to generically as "perfume."

Historically, women's fragrances tended to have higher levels of aromatic compounds than men's fragrances. Fragrances marketed to men were typically sold as EdT or EdC, rarely as EdP or perfume extracts. This is changing in the modern fragrance world, especially as fragrances are becoming more unisex. Women's fragrances used to be common in all levels of concentration, but in the 21st century are mainly seen in EdP and EdT concentrations. Many modern perfumes are never offered in extrait or eau de cologne formulations, and EdP and EdT account for the vast majority of new launches.

Solvent types

Perfume oils are often diluted with a solvent, though this is not always the case, and its necessity is disputed. By far the most common solvent for perfume-oil dilution is alcohol, typically a mixture of ethanol and water or a rectified spirit. Perfume oil can also be diluted by means of neutral-smelling oils such as fractionated coconut oil, or liquid waxes such as jojoba oil and almond oil.

Applying fragrances

The conventional application of pure perfume (parfum extrait) in Western cultures is behind the ears, at the nape of the neck, under the armpits and at the insides of wrists, elbows and knees, so that the pulse point will warm the perfume and release fragrance continuously. According to perfumer Sophia Grojsman behind the knees is the ideal point to apply perfume in order that the scent may rise. The modern perfume industry encourages the practice of layering fragrance so that it is released in different intensities depending upon the time of the day. Lightly scented products such as bath oil, shower gel, and body lotion are recommended for the morning; eau de toilette is suggested for the afternoon; and perfume applied to the pulse points for evening. Cologne fragrance is released rapidly, lasting around 2 hours. Eau de toilette lasts from 2 to 4 hours, while perfume may last up to six hours.

A variety of factors can influence how fragrance interacts with the wearer's own physiology and affect the perception of the fragrance. Diet is one factor, as eating spicy and fatty foods can increase the intensity of a fragrance. The use of medications can also impact the character of a fragrance. The relative dryness of the wearer's skin is important, since dry skin will not hold fragrance as long as skin with more oil.

Describing a perfume

The precise formulae of commercial perfumes are kept secret. Even if they were widely published, they would be dominated by such complex ingredients and odorants that they would be of little use in providing a guide to the general consumer in description of the experience of a scent. Nonetheless, connoisseurs of perfume can become extremely skillful at identifying components and origins of scents in the same manner as wine experts.

The most practical way to start describing a perfume is according to the elements of the fragrance notes of the scent or the "family" it belongs to, all of which affect the overall impression of a perfume from first application to the last lingering hint of scent.

The trail of scent left behind by a person wearing perfume is called its sillage, after the French word for "wake", as in the trail left by a boat in water.

Fragrance notes

Main article: Note (perfumery)Perfume is described in a musical metaphor as having three sets of notes, making the harmonious scent accord. The notes unfold over time, with the immediate impression of the top note leading to the deeper middle notes, and the base notes gradually appearing as the final stage. These notes are created carefully with knowledge of the evaporation process of the perfume.

- Top notes: Also called the head notes. The scents that are perceived immediately on application of a perfume. Top notes consist of small, light molecules that evaporate quickly. They form a person's initial impression of a perfume and thus are very important in the selling of a perfume. Examples of top notes include mint, lavender and coriander.

- Middle notes: Also referred to as heart notes. The scent of a perfume that emerges just prior to the dissipation of the top note. The middle note compounds form the "heart" or main body of a perfume and act to mask the often unpleasant initial impression of base notes, which become more pleasant with time. Examples of middle notes include seawater, sandalwood and jasmine.

- Base notes: The scent of a perfume that appears close to the departure of the middle notes. The base and middle notes together are the main theme of a perfume. Base notes bring depth and solidity to a perfume. Compounds of this class of scents are typically rich and "deep" and are usually not perceived until 30 minutes after application. Examples of base notes include tobacco, amber and musk.

The scents in the top and middle notes are influenced by the base notes; conversely, the scents of the base notes will be altered by the types of fragrance materials used as middle notes. Manufacturers who publish perfume notes typically do so with the fragrance components presented as a fragrance pyramid, using imaginative and abstract terms for the components listed.

Olfactive families

The grouping of perfumes can never be completely objective or definitive. Many fragrances contain aspects of different families. Even a perfume designated as "single flower" will have subtle undertones of other aromatics. There are hardly any true unitary-scent perfumes consisting of a single aromatic material.

The family classification is a starting point to describe a perfume, but does not fully characterize it.

Traditional categories

The traditional categories which emerged around 1900:

- Citrus: The oldest fragrance family that gave birth to lightweight eau de colognes. Development of newer fragrance compounds has allowed for the creation of more tenacious citrus fragrances. Examples: 4711, Guerlain's Eau de Cologne Impériale, Penhaligon's Quercus.

- Single Floral: Fragrances dominated by the scent of a particular flower, i.e., rose, carnation, iris. In French this type of fragrance is called a soliflore. Example: Serge Lutens Sa Majeste La Rose.

- Floral Bouquet: Compound of several flower scents. Examples: Houbigant Quelques Fleurs, Jean Patou Joy.

- Amber or "Oriental": Large class featuring sweet, slightly animalic scents of ambergris or labdanum, often combined with vanilla, tonka bean, flowers and woods. Can be enhanced by camphorous oils and incense resins, evoking Victorian era "Oriental" imagery. Traditional examples: Guerlain Shalimar, Yves Saint Laurent Opium, Chanel Coco Mademoiselle.

- Woody: Fragrances dominated by woody notes, typically agarwood, sandalwood, cedarwood, and vetiver. Patchouli, with its camphoraceous smell, is commonly found in these perfumes. Traditional examples: Myrurgia Maderas De Oriente, Chanel Bois des Îles. Modern: Balenciaga Rumba.

- Leather: A family of fragrances featuring honey, tobacco, wood and wood tars in the middle or base notes and a scent that alludes to leather. Traditional examples: Robert Piguet Bandit, Balmain Jolie Madame.

- Chypre (IPA: [ʃipʁ]): Meaning Cyprus in French, this category is named after the François Coty's Chypre (1917), which was the first modern fragrance built on an accord of bergamot, oakmoss, and labdanum. Example: Guerlain Mitsouko, Rochas Femme.

- Fougère (IPA: [fu.ʒɛʁ]): Meaning fern in French, built on a base of lavender, coumarin and oakmoss, with a sharp herbaceous and woody scent. Named for Houbigant's landmark fragrance Fougère Royale, many men's fragrances belong to this family. Modern examples: Fabergé Brut, Guy Laroche Drakkar Noir, Penhaligon's Douro.

Modern

Since 1945, new categories have emerged to describe modern scents, due to great advances in the technology of compound design and synthesis, as well as the natural development of styles and tastes:

- Bright Floral: Combining single floral and floral bouquet traditional categories. Example: Estée Lauder Beautiful.

- Green: Lighter, more modern interpretation of the Chypre type, with pronounced cut grass, crushed green leaf and cucumber-like scents. Examples: Estée Lauder Aliage, Sisley Eau de Campagne, Calvin Klein Eternity.

- Aquatic, Oceanic, Ozonic: The newest category, first appearing in 1988 Davidoff Cool Water (1988), Christian Dior Dune (1991). A clean smell reminiscent of the ocean, leading to many androgynous perfumes. Generally contains calone, a synthetic discovered in 1966, or more recent synthetics. Also used to accent floral, oriental, and woody fragrances.

- Fruity: Featuring fruits other than citrus, such as peach, cassis (blackcurrant), mango, passionfruit, and others. Example: Ginestet Botrytis.

- Gourmand (French: [ɡuʁmɑ̃]): Scents with "edible" or "dessert-like" qualities, often containing vanilla, tonka bean, and coumarin, as well as synthetic components designed to resemble food flavors. Example: Thierry Mugler's Angel.

Fragrance wheel

Main article: Fragrance wheel

This newer classification method is widely used in retail and the fragrance industry, created in 1983 by the perfume consultant Michael Edwards. The new scheme simplifies classification and naming, as well as showing the relationships among the classes.

The five main families are Floral, Oriental, Woody, Aromatic Fougère, and Fresh, the first four from the classic terminology and the last from the modern oceanic category. Each of these are divided into subgroups and arranged around a wheel. In this scheme, Chanel No.5, traditionally classified as an aldehydic floral, is placed under the Soft Floral sub-group, while amber scents are within the Oriental group. Chypre perfumes are more ambiguous, having affinities with both the Oriental and Woody families. For instance, Guerlain Mitsouko is under Mossy Woods, but Hermès Rouge, a more floral chypre, is under Floral Oriental.

Aromatics sources

Plant sources

Plants have long been used in perfumery as a source of essential oils and aroma compounds. These aromatics are usually secondary metabolites produced by plants as protection against herbivores, infections, as well as to attract pollinators. Plants are by far the largest source of fragrant compounds used in perfumery. The sources of these compounds may be derived from various parts of a plant. A plant can offer more than one source of aromatics, for instance the aerial portions and seeds of coriander have remarkably different odors from each other. Orange leaves, blossoms, and fruit zest are the respective sources of petitgrain, neroli, and orange oils.

- Bark: Commonly used barks include cinnamon and cascarilla. The fragrant oil in sassafras root bark is also used either directly or purified for its main constituent, safrole, which is used in the synthesis of other fragrant compounds.

- Flowers and blossoms: Undoubtedly the largest and most common source of perfume aromatics. Includes the flowers of several species of rose and jasmine, as well as osmanthus, plumeria, mimosa, tuberose, narcissus, scented geranium, cassie, ambrette as well as the blossoms of citrus and ylang-ylang trees. Although not traditionally thought of as a flower, the unopened flower buds of the clove are also commonly used. Most orchid flowers are not commercially used to produce essential oils or absolutes, except in the case of vanilla, an orchid, which must be pollinated first and made into seed pods before use in perfumery.

- Fruits: Fresh fruits such as apples, strawberries, cherries rarely yield the expected odors when extracted; if such fragrance notes are found in a perfume, they are more likely to be of synthetic origin. Notable exceptions include blackcurrant leaf, litsea cubeba, vanilla, and juniper berry. The most commonly used fruits yield their aromatics from the rind; they include citrus such as oranges, lemons, and limes. Although grapefruit rind is still used for aromatics, more and more commercially used grapefruit aromatics are artificially synthesized since the natural aromatic contains sulfur and its degradation product is quite unpleasant in smell.

- Leaves and twigs: Commonly used for perfumery are lavender leaf, patchouli, sage, violets, rosemary, and citrus leaves. Sometimes leaves are valued for the "green" smell they bring to perfumes, examples of this include hay and tomato leaf.

- Resins: Valued since antiquity, resins have been widely used in incense and perfumery. Highly fragrant and antiseptic resins and resin-containing perfumes have been used by many cultures as medicines for a large variety of ailments. Commonly used resins in perfumery include labdanum, frankincense/olibanum, myrrh, balsam of Peru, benzoin. Pine and fir resins are a particularly valued source of terpenes used in the organic synthesis of many other synthetic or naturally occurring aromatic compounds. Some of what is called amber and copal in perfumery today is the resinous secretion of fossil conifers.

- Roots, rhizomes and bulbs: Commonly used terrestrial portions in perfumery include iris rhizomes, vetiver roots, various rhizomes of the ginger family.

- Seeds: Commonly used seeds include tonka bean, carrot seed, coriander, caraway, cocoa, nutmeg, mace, cardamom, and anise.

- Woods: Highly important in providing the base notes to a perfume, wood oils and distillates are indispensable in perfumery. Commonly used woods include sandalwood, rosewood, agarwood, birch, cedar, juniper, and pine. These are used in the form of macerations or dry-distilled (rectified) forms.

- Rom terpenes. Orchid scents

Animal sources

- Ambergris: Lumps of oxidized fatty compounds, whose precursors were secreted and expelled by the sperm whale. Ambergris should not be confused with yellow amber, which is used in jewelry. Because the harvesting of ambergris involves no harm to its animal source, it remains one of the few animalic fragrancing agents around which little controversy now exists.

- Castoreum: Obtained from the odorous sacs of the North American beaver.

- Civet: Also called civet musk, this is obtained from the odorous sacs of the civets, animals in the family Viverridae, related to the mongoose. World Animal Protection investigated African civets caught for this purpose.

- Hyraceum: Commonly known as "Africa stone", is the petrified excrement of the rock hyrax.

- Honeycomb: From the honeycomb of the honeybee. Both beeswax and honey can be solvent extracted to produce an absolute. Beeswax is extracted with ethanol and the ethanol evaporated to produce beeswax absolute.

- Musk: Originally derived from a gland (sac or pod) located between the genitals and the umbilicus of the Himalayan male musk deer Moschus moschiferus, it has now mainly been replaced by the use of synthetic musks sometimes known as "white musk".

Other natural sources

- Lichens: Commonly used lichens include oakmoss and treemoss thalli.

- "Seaweed": Distillates are sometimes used as essential oil in perfumes. An example of a commonly used seaweed is Fucus vesiculosus, which is commonly referred to as bladder wrack. Natural seaweed fragrances are rarely used due to their higher cost and lower potency than synthetics.

Synthetic sources

Main article: Aroma compoundMany modern perfumes contain synthesized odorants. Synthetics can provide fragrances which are not found in nature. For instance, Calone, a compound of synthetic origin, imparts a fresh ozonous metallic marine scent that is widely used in contemporary perfumes. Synthetic aromatics are often used as an alternate source of compounds that are not easily obtained from natural sources. For example, linalool and coumarin are both naturally occurring compounds that can be inexpensively synthesized from terpenes. Orchid scents (typically salicylates) are usually not obtained directly from the plant itself but are instead synthetically created to match the fragrant compounds found in various orchids.

One of the most commonly used classes of synthetic aromatics by far are the white musks. These materials are found in all forms of commercial perfumes as a neutral background to the middle notes. These musks are added in large quantities to laundry detergents in order to give washed clothes a lasting "clean" scent.

The majority of the world's synthetic aromatics are created by relatively few companies. They include:

Each of these companies patents several processes for the production of aromatic synthetics annually.

Characteristics

Natural and synthetics are used for their different odor characteristics in perfumery

| Naturals | Synthetics | |

|---|---|---|

| Variance | Natural scents will vary from each supplier based on when and where they are harvested, how they are processed, and the extraction method itself. This means that a certain flower grown in Morocco and in France will smell different, even if the same method is used to grow, harvest, and extract the scent. As such, each perfumer will prefer flowers grown in one country over another, or one extraction method to the next. However, due to a natural scent's mixed composition, it is easy for unscrupulous suppliers to adulterate the actual raw materials by changing its source (adding Indian jasmine into Grasse jasmine) or the contents (adding linalool to rosewood) to increase their profit margin. | Much more consistent than natural aromatics. However, differences in organic synthesis may result in minute differences in concentration of impurities. If these impurities have low smell (detection) thresholds, the differences in the scent of the synthetic aromatic will be significant. |

| Components | Contains many different organic compounds, each adding a different note to the overall scent. Certain naturally derived substances have a long history of use, but this cannot always be used as an indicator of whether they are safe or not. Possible allergenic or carcinogenic compounds. | Depending on purity, consists primarily of one chemical compound. Sometimes chiral mixtures of isomers, such as in the case of Iso E Super. Due to the almost pure composition of one chemical compound, the same molecules found diluted in nature will have a different scent and effect on the body, if used undiluted. |

| Scent uniqueness | Reminiscent of its originating material, although extraction may capture a different "layer" of the scent, depending on how the extraction method denatures the odoriferous compounds. | Similar to natural scents yet different at the same time. Some synthetics attempt to mimic natural notes, while others explore the entire spectrum of scent. Novel scent compounds not found in nature will often be unique in their scent. |

| Scent complexity | Deep and complex fragrance notes. Soft, with subtle scent nuances. Highly valued for ideal composition. | Pure and pronounced fragrance notes. Often monotonous in nature, yet reminiscent of other natural scents. |

| Price | Dependent on extraction method. More expensive, but not always, as prices are determined by the labor and difficulty of properly extracting each unit of the natural materials, as well as its quality. Typically the relationship between, longevity of a perfume, cost and the concentration of essential oils follows the graph below:

|

Dependent on synthesis method. Generally cheaper, but not necessarily. Synthetic aromatics are not necessarily cheaper than naturals, with some synthetics being more costly than most natural ingredients due to various factors such as the long synthesis routes, low availability of precursor chemicals, and low overall yield. However, due to their low odor threshold, they should be diluted when making a perfume. |

Obtaining natural odorants

Main article: Fragrance extraction

Before perfumes can be composed, the odorants used in various perfume compositions must first be obtained. Synthetic odorants are produced through organic synthesis and purified. Odorants from natural sources require the use of various methods to extract the aromatics from the raw materials. The results of the extraction are either essential oils, absolutes, concretes, or butters, depending on the amount of waxes in the extracted product.

All these techniques will, to a certain extent, distort the odor of the aromatic compounds obtained from the raw materials. This is due to the use of heat, harsh solvents, or through exposure to oxygen in the extraction process which will denature the aromatic compounds, which either change their odor character or renders them odorless.

- Maceration/Solvent extraction: The most used and economically important technique for extracting aromatics in the modern perfume industry. Raw materials are submerged in a solvent that can dissolve the desired aromatic compounds. Maceration lasts anywhere from hours to months. Fragrant compounds for woody and fibrous plant materials are often obtained in this manner as are all aromatics from animal sources. The technique can also be used to extract odorants that are too volatile for distillation or easily denatured by heat. Commonly used solvents for maceration/solvent extraction include ethane, hexane, and dimethyl ether. The product of this process is called a "concrete."

- Supercritical fluid extraction: A relatively new technique for extracting fragrant compounds from a raw material, which often employs Supercritical CO2. Due to the low heat of process and the relatively nonreactive solvent used in the extraction, the fragrant compounds derived often closely resemble the original odor of the raw material.

- Ethanol extraction: A type of solvent extraction used to extract fragrant compounds directly from dry raw materials, as well as the impure oily compounds materials resulting from solvent extraction or enfleurage. Ethanol extraction from fresh plant materials contain large quantities of water, which will also be extracted into the ethanol.

- Distillation: A common technique for obtaining aromatic compounds from plants, such as orange blossoms and roses. The raw material is heated and the fragrant compounds are re-collected through condensation of the distilled vapor.

- Steam distillation: Steam from boiling water is passed through the raw material, which drives out their volatile fragrant compounds. The condensate from distillation are settled in a Florentine flask. This allows for the easy separation of the fragrant oils from the water. The water collected from the condensate, which retains some of the fragrant compounds and oils from the raw material is called hydrosol and sometimes sold. This is most commonly used for fresh plant materials such as flowers, leaves, and stems.

- Dry/destructive distillation: The raw materials are directly heated in a still without a carrier solvent such as water. Fragrant compounds that are released from the raw material by the high heat often undergo anhydrous pyrolysis, which results in the formation of different fragrant compounds, and thus different fragrant notes. This method is used to obtain fragrant compounds from fossil amber and fragrant woods where an intentional "burned" or "toasted" odor is desired.

- Fractionation: Through the use of a fractionation column, different fractions distilled from a material can be selectively excluded to modify the scent of the final product. Although the product is more expensive, this is sometimes performed to remove unpleasant or undesirable scents of a material and affords the perfumer more control over their composition process.

- Expression: Raw material is squeezed or compressed and the essential oils are collected. Of all raw materials, only the fragrant oils from the peels of fruits in the citrus family are extracted in this manner since the oil is present in large enough quantities as to make this extraction method economically feasible.

- Enfleurage: Absorption of aroma materials into solid fat or wax and then extraction of odorous oils with ethyl alcohol. Extraction by enfleurage was commonly used when distillation was not possible because some fragrant compounds denature through high heat. This technique is not commonly used in the modern industry due to prohibitive costs and the existence of more efficient and effective extraction methods.

Fragrant extracts

Although fragrant extracts are known to the general public as the generic term "essential oils", a more specific language is used in the fragrance industry to describe the source, purity, and technique used to obtain a particular fragrant extract. Of these extracts, only absolutes, essential oils, and tinctures are directly used to formulate perfumes.

- Absolute: Fragrant materials that are purified from a pommade or concrete by soaking them in ethanol. By using a slightly hydrophilic compound such as ethanol, most of the fragrant compounds from the waxy source materials can be extracted without dissolving any of the fragrantless waxy molecules. Absolutes are usually found in the form of an oily liquid.

- Concrete: Fragrant materials that have been extracted from raw materials through solvent extraction using volatile hydrocarbons. Concretes usually contain a large amount of wax due to the ease in which the solvents dissolve various hydrophobic compounds. As such concretes are usually further purified through distillation or ethanol based solvent extraction. Concretes are typically either waxy or resinous solids or thick oily liquids.

- Essential oil: Fragrant materials that have been extracted from a source material directly through distillation or expression and obtained in the form of an oily liquid. Oils extracted through expression are sometimes called expression oils.

- Pomade: A fragrant mass of solid fat created from the enfleurage process, in which odorous compounds in raw materials are adsorbed into animal fats. Pommades are found in the form of an oily and sticky solid.

- Tincture: Fragrant materials produced by directly soaking and infusing raw materials in ethanol. Tinctures are typically thin liquids.

Products from different extraction methods are known under different names even though their starting materials are the same. For instance, orange blossoms from Citrus aurantium that have undergone solvent extraction produces "orange blossom absolute" but that which have been steam distilled is known as "neroli oil".

Composing perfumes

Perfume compositions are an important part of many industries ranging from the luxury goods sectors, food services industries, to manufacturers of various household chemicals. The purpose of using perfume or fragrance compositions in these industries is to affect customers through their sense of smell and entice them into purchasing the perfume or perfumed product. As such there is significant interest in producing a perfume formulation that people will find aesthetically pleasing.

The perfumer

Main article: Perfumer

The job of composing perfumes that will be sold is left up to an expert on perfume composition or known in the fragrance industry as the perfumer. They are also sometimes referred to affectionately as a "Nez" (French for nose) due to their fine sense of smell and skill in smell composition.

The composition of a perfume typically begins with a brief by the perfumer's employer or an outside customer. The customers to the perfumer or their employers, are typically fashion houses or large corporations of various industries. The perfumer will then go through the process of blending multiple perfume mixtures and sell the formulation to the customer, often with modifications of the composition of the perfume. The perfume composition will then be either used to enhance another product as a functional fragrance (shampoos, make-up, detergents, car interiors, etc.), or marketed and sold directly to the public as a fine fragrance.

Technique

Although there is no single "correct" technique for the formulation of a perfume, there are general guidelines as to how a perfume can be constructed from a concept. Although many ingredients do not contribute to the smell of a perfume, many perfumes include colorants and antioxidants to improve the marketability and shelf life of the perfume, respectively.

Basic framework

Perfume oils usually contain tens to hundreds of ingredients and these are typically organized in a perfume for the specific role they will play. These ingredients can be roughly grouped into four groups:

- Primary scents (Heart): Can consist of one or a few main ingredients for a certain concept, such as "rose". Alternatively, multiple ingredients can be used together to create an "abstract" primary scent that does not bear a resemblance to a natural ingredient. For instance, jasmine and rose scents are commonly blends for abstract floral fragrances. Cola flavourant is a good example of an abstract primary scent.

- Modifiers: These ingredients alter the primary scent to give the perfume a certain desired character: for instance, fruit esters may be included in a floral primary to create a fruity floral; calone and citrus scents can be added to create a "fresher" floral. The cherry scent in cherry cola can be considered a modifier.

- Blenders: A large group of ingredients that smooth out the transitions of a perfume between different "layers" or bases. These themselves can be used as a major component of the primary scent. Common blending ingredients include linalool and hydroxycitronellal.

- Fixatives: Used to support the primary scent by bolstering it. Many resins, wood scents, and amber bases are used as fixatives.

The top, middle, and base notes of a fragrance may have separate primary scents and supporting ingredients. The perfume's fragrance oils are then blended with ethyl alcohol and water, aged in tanks for several weeks and filtered through processing equipment to, respectively, allow the perfume ingredients in the mixture to stabilize and to remove any sediment and particles before the solution can be filled into the perfume bottles.

Fragrance bases

Instead of building a perfume from "ground up", many modern perfumes and colognes are made using fragrance bases or simply bases. Each base is essentially modular perfume that is blended from essential oils and aromatic chemicals, and formulated with a simple concept such as "fresh cut grass" or "juicy sour apple". Many of Guerlain's Aqua Allegoria line, with their simple fragrance concepts, are good examples of what perfume fragrance bases are like.

The effort used in developing bases by fragrance companies or individual perfumers may equal that of a marketed perfume, since they are useful in that they are reusable. On top of its reusability, the benefit in using bases for construction are quite numerous:

- Ingredients with "difficult" or "overpowering" scents that are tailored into a blended base may be more easily incorporated into a work of perfume

- A base may be better scent approximations of a certain thing than the extract of the thing itself. For example, a base made to embody the scent for "fresh dewy rose" might be a better approximation for the scent concept of a rose after rain than plain rose oil. Flowers whose scents cannot be extracted, such as gardenia or hyacinth, are composed as bases from data derived from headspace technology.

- A perfumer can quickly rough out a concept from a brief by combining multiple bases, then present it for feedback. Smoothing out the "edges" of the perfume can be done after a positive response.

Reverse engineering

Creating perfumes through reverse engineering with analytical techniques such as Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) can reveal the "general" formula for any particular perfume. The difficulty of GC/MS analysis arises due to the complexity of a perfume's ingredients. This is particularly due to the presence of natural essential oils and other ingredients consisting of complex chemical mixtures. However, "anyone armed with good GC/MS equipment and experienced in using this equipment can today, within days, find out a great deal about the formulation of any perfume... customers and competitors can analyze most perfumes more or less precisely."

Antique or badly preserved perfumes undergoing this analysis can also be difficult due to the numerous degradation by-products and impurities that may have resulted from breakdown of the odorous compounds. Ingredients and compounds can usually be ruled out or identified using gas chromatograph (GC) smellers, which allow individual chemical components to be identified both through their physical properties and their scent. Reverse engineering of best-selling perfumes in the market is a very common practice in the fragrance industry due to the relative simplicity of operating GC equipment, the pressure to produce marketable fragrances, and the highly lucrative nature of the perfume market.

Copyright

It is doubtful whether perfumes qualify as appropriate copyright subject matter under the US Copyright Act. The issue has not yet been addressed by any US court. A perfume's scent is not eligible for trademark protection: the scent serves as the functional purpose of the product.

In 2006 the Dutch Supreme Court granted copyright protection to Lancôme's perfume Tresor (Lancôme v. Kecofa).

The French Supreme Court has twice taken the position that perfumes lack the creativity to constitute copyrightable expressions (Bsiri-Barbir v. Haarman & Reimer, 2006; Beaute Prestige International v. Senteur Mazal, 2008).

Sometimes, a knock-off perfume would use an altered name of the original perfume (for instance, now-discontinued Freya by Oriflame perfume has a similar-designed copy produced as "Freyya").

It is still questionable if perfume's "functional purpose" can be protected with technical patent (one which lasts 15 years). Apparently, Russian "Novaya Zarya" labels their colognes as "hygienic lotions" for a similar reason. A counterexample: NovZar's more-than-century-old Shipr chypre and Troinoi cologne are being produced by other companies in Russia in similar bottles.

Numbered perfumery, "analogs"

A different kind of copying perfumes is known in ex-USSR countries as "номерная парфюмерия" (literally "numbered perfumery"):

A "number-making" company with perfumery equipment would use their own, one-style-for-all cheap bottle; de jure labeling a knock-off perfume as an "aroma in the direction of " or a "version" of certain branded perfume. This way, the production costs of initially cheap scents are reduced, since the bottle is used neither for plain counterfeiting nor for subtle re-designing.

The questionable part of numbered perfumery naming is the idea to openly mark perfume #XXX (say, #105) as either "type" or "version", or "аромат направления" (literally "aroma in the direction of") of a well-known perfum.

- Resellers in offline stores (in malls, airport shops) can offer "fillable" perfumery, sometimes using weasel wording to justify the price.

- Such perfumes usually get three-digit numbers as an officially registered name, which is stickered to the bottles.

- When it comes to propellant, a "number" usually has an alcohol base without stabilization (which may give strong "alcohol base stench", altering perfume's scent into the "smell of cheapness" phenomenon).

- To avoid this, many "numbers" can be made with (di)propylenglicol base and come as "perfume oil(s)". PG or DPG based numbered perfumery comes in 50ml plastic bottles and is purposed for tiny rollers; (D)PG is not usable in spray bottles (while not affected by the "smell of cheapness" issue nonetheless). Some companies offer all of their own "numbers" in both alcohol based and (D)PG based variants.

In small online "bulk", however (in purchases over 5000RUB), a whole 100ml bottle of such perfume (or 50ml bottle of "scent oil" of same "direction") costs only around 6 EUR.

Health and environmental issues

Perfume ingredients, regardless of natural or synthetic origins, may all cause health or environmental problems when used. Although the areas are under active research, much remains to be learned about the effects of fragrance on human health and the environment.

Immunological; asthma and allergy

Evidence in peer-reviewed journals shows that some fragrances can cause asthmatic reactions in some individuals, especially those with severe or atopic asthma. Many fragrance ingredients can also cause headaches, allergic skin reactions or nausea.

In some cases, an excessive use of perfumes may cause allergic reactions of the skin. For instance, acetophenone, ethyl acetate and acetone while present in many perfumes, are also known or potential respiratory allergens. Nevertheless, this may be misleading, since the harm presented by many of these chemicals (either natural or synthetic) is dependent on environmental conditions and their concentrations in a perfume. For instance, linalool, which is listed as an irritant, causes skin irritation when it degrades to peroxides, however the use of antioxidants in perfumes or reduction in concentrations can prevent this. As well, the furanocoumarin present in natural extracts of grapefruit or celery can cause severe allergic reactions and increase sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation.

Some research on natural aromatics have shown that many contain compounds that cause skin irritation. However some studies, such as IFRA's research claim that opoponax is too dangerous to be used in perfumery, still lack scientific consensus. It is also true that sometimes inhalation alone can cause skin irritation.

A number of national and international surveys have identified balsam of Peru, often used in perfumes, as being in the "top five" allergens most commonly causing patch test reactions in people referred to dermatology clinics. A study in 2001 found that 3.8% of the general population patch tested was allergic to it. Many perfumes contain components identical to balsam of Peru.

Balsam of Peru is used as a marker for perfume allergy. Its presence in a cosmetic is denoted by the INCI term Myroxylon pereirae. Balsam of Peru has been banned by the International Fragrance Association since 1982 from use as a fragrance compound, but may be present as an extract or distillate in other products, where mandatory labelling is not required for usage of 0.4% or less.

Carcinogenicity

There is scientific evidence that nitro-musks such as musk xylene could cause cancer in some specific animal tests. These reports were evaluated by the EU Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety (SCCS, formerly the SCCNFP) and musk xylene was found to be safe for continued use in cosmetic products. It is in fact part of the procedures of the Cosmetic Regulation in Europe that materials classified as carcinogens require such a safety evaluation by the authorities to be allowed in cosmetic consumer products.

Although other ingredients such as polycyclic synthetic musks, have been reported to be positive in some in-vitro hormone assays, these reports have been reviewed by various authorities. For example, for one of the main polycyclic musks Galaxolide (HHCB) these reviews include those of the EU Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety, the EU's Priority Substances Review, the EU Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risk, and more recently also the US EPA. The outcome of all of these reviews over the past decade or so is that there are no safety concerns for human health. Reviews with similar positive outcomes also exist for another main polycyclic musk (AHTN)—for instance, on its safe use in cosmetics by the EU.

Many natural aromatics, such as oakmoss absolutes, basil oil, rose oil and many others contain allergens or carcinogenic compounds, the safety of which is either governed by regulations (e.g. allowed methyl eugenol levels in the EU Cosmetics Regulation (Entry 102, Annex III of the EU Cosmetics Regulation.) or through various limitations set by the International Fragrance Association.

Environmental

Pollution

Synthetic musks are pleasant in smell and relatively inexpensive, as such they are often employed in large quantities to cover the unpleasant scent of laundry detergents and many personal cleaning products. Due to their large-scale use, several types of synthetic musks have been found in human fat and milk, as well as in the sediments and waters of the Great Lakes.

These pollutants may pose additional health and environmental problems when they enter human and animal diets.

Species endangerment

The demands for aromatic materials such as sandalwood, agarwood, and musk have led to the endangerment of these species, as well as illegal trafficking and harvesting.

Safety regulations

The US FDA controls the safety of perfumes through their ingredients and requires that they be tested to the extent that they are Generally recognized as safe (GRAS). Due to the need for protection of trade secrets, companies rarely give the full listing of ingredients regardless of their effects on health.

In the EU, as from 11 March 2005, the mandatory listing of a set of 26 recognized fragrance allergens was enforced. The requirement to list these materials is dependent on the intended use of the final product. The limits above which the allergens are required to be declared are 0.001% for products intended to remain on the skin, and 0.01% for those intended to be rinsed off. This has resulted in many old perfumes like chypres and fougère classes, which traditionally make use of oakmoss extract, being reformulated.

Preserving perfume

Fragrance compounds in perfumes will degrade or break down if improperly stored in the presence of heat, light, oxygen, and extraneous organic materials. Proper preservation of perfumes involves keeping them away from sources of heat and storing them where they will not be exposed to light. An opened bottle will keep its aroma intact for several years, as long as it is well stored. However, the presence of oxygen in the head space of the bottle and environmental factors will in the long run alter the smell of the fragrance.

Perfumes are best preserved when kept in light-tight aluminium bottles or in their original packaging when not in use, and refrigerated to relatively low temperatures: between 3–7 °C (37–45 °F). Although it is difficult to completely remove oxygen from the headspace of a stored flask of fragrance, opting for spray dispensers instead of rollers and "open" bottles will minimize oxygen exposure. Sprays also have the advantage of isolating fragrance inside a bottle and preventing it from mixing with dust, skin, and detritus, which would degrade and alter the quality of a perfume.

There exist several archives and museums devoted to the preservation of historical perfumes, namely the Osmothèque, which stocks over 3,000 perfumes from the past two millennia in their original formulations. All scents in their collection are preserved in non-actinic glass flasks flushed with argon gas, stored in thermally insulated compartments maintained at 12 °C (54 °F) in a large vault.

Lists of perfumes

Further information: List of perfumes, List of essential oils, and List of celebrity-branded fragrancesSee also

- Odor – Volatile chemical compounds perceived by the sense of smell

- Pheromone – Secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species

- Eau de toilette – Lightly scented perfume

- Eau de Cologne – Type of perfume

- Scented water – Lightly scented perfumePages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Essential oil – Hydrophobic liquid containing volatile aroma compounds from plants

- Aromatherapy – Use of aromas during meditation or relaxation

- Fragrance companies

- Fragrance Museum – museum in Cologne, GermanyPages displaying wikidata descriptions as a fallback

- John Maria Farina opposite Jülich's Square – World's oldest perfume factory

- FiFi Awards – Fragrance industry awards

- Potpourri – Mixture of dried flowers and other naturally fragrant plant material

- Pomander – Ball or container of herbs and perfumes

- Fragrance lamp – Lamp that disperses scented alcohol

- Flanker (perfume) – Derivative or offshoot of an existing perfume

References

- "Perfume – Definition and More from Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Shyndriayeva, Galina (2015). "Perfume at the Forefront of Macrocyclic Compound Research: From Switzerland to Du Pont" (PDF). International Workshop on the History of Chemistry. Tokyo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- "perfume". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- Balasubramanian, Narayanaganesh (20 November 2015). "Scented Oils and Perfumes". American Chemical Society. ACS Symposium Series. 1211: 219–244. doi:10.1021/bk-2015-1211.ch008. ISBN 9780841231122. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Strathern, Paul (2000). Mendeleyev's Dream – The Quest For the Elements. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-18467-6.

- Levey, Martin (1973). Early Arabic Pharmacology: An Introduction Based on Ancient and Medieval Sources. Brill Archive. p. 9. ISBN 90-04-03796-9.

- A.K. Sharma; Seema Wahad; Raśmī Śrīvāstava (2010). Agriculture Diversification: Problems and Perspectives. I. K. International Pvt Ltd. p. 140.

- ^ Roach, John (29 March 2007). "Oldest Perfumes Found on "Aphrodite's Island"". Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- "Ancient Perfumes Recreated, Put on Display in Rome". Fox News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2007.

- Elis, Kiss (2 June 2018). "Ancient perfume recreated for anniversary show". Kathimerini English Edition. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Kidd, Benton. "Perfumery in Ancient Greek and Roman Societies" (PDF). Museum of Art and Archaeology | University of Missouri.

- al-Hassani, Woodcok and Saoud (2006) 1001 Inventions; Muslim Heritage in Our World, FSTC, p.22.

- M. Ullmann (1986), "AL-KĪMIYĀ", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 5 (2nd ed.), Brill, p. 111b

- E. Wiedemann; M. Plessner (1986), "AL-ANBĪḲ", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 1 (2nd ed.), Brill, p. 486a

- Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott, eds. (1897), "ἄμβιξ", Greek-English Lexicon (8th ed.), Harper & Brothers, p. 73

- Marcellin Berthelot (1889), Introduction à l'étude de la chimie des anciens et du moyen âge, Steinheil, p. 164, archived from the original on 23 November 2020, retrieved 13 October 2014

- "History of Perfumes in Spain". La Casa Mundo. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- Giovanni Dugo, Ivana Bonaccorsi (2013). Citrus bergamia: Bergamot and its Derivatives. CRC Press. p. 467. ISBN 9781439862292.

- Thompson, C.J.S. (1927). The Mystery and Lure of Perfume. London: John Lane the Bodley Head Limited. p. 140.

- Voudouri, Dimitra; Tesseromatis, Christine (December 2015). "Perfumery from Myth to Antiquity" (PDF). International Journal of Medicine and Pharmacy. 3 (2): 52. doi:10.15640/ijmp.v3n2a4 (inactive 1 November 2024). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Sullivan, Catherine (1 March 1994). "Searching for nineteenth-century Florida water bottles". Historical Archaeology. 28 (1): 78–98. doi:10.1007/BF03374182. ISSN 0440-9213. S2CID 162639733.

- Stoddart, David Michael (1990). The Scented Ape: The Biology and Culture of Human Odour. Cambridge University Press. pp. 142–167.

- Compare: Pepe, Tracy (2000). So, What's All the Sniff About?: An In-Depth Plea for Sanity and Equal Rights for Your Sense of Smell, Our Most Neglected and Endangered Sense. So Whats all the Sniff about. p. 46. ISBN 9780968707609. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

In 1693 an Italian, Giovanni Paolo de Feminis created a fragrance called "Aqua Mirabilis". This fragrance was said to have therapeutic properties to aid with headaches and heart palpitations. It was designed as a non-gender aroma that would enhance one's mood.

- "A Brief History of Men's Cologne – Discover the History of Men's Fragrances-COLOGNE BLOG". COLOGNE BLOG. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014.

- Charles Rice, Frederick Albert Castle (1879). New Remedies: An Illustrated Monthly Trade Journal of Materia Medica, Pharmacy and Therapeutics. W. Wood & Company. p. 358.

- ^ Tynan Sinks (12 July 2018). "The Difference Between Perfume, Cologne and Other Fragrances". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

You'll see all sorts of names in the fragrance section: perfume, eau de toilette, parfum, eau de cologne. What makes them different — and in many cases, more expensive?

- "Scents from Vienna". wien.info. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Glossary (C)". The Fragrance Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "A Guide to Perfume Types". Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Berger, Paul (26 October 2011). "Perfume 'Nose' Conjures Up Perfect Scents". Forward.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Agata A. Listowska, MA & Mark A. Nicholson, ASO (2011). Complementary Medicine, Beauty and Modelling. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 153–4. ISBN 9781456888954.

- ^ Turkington, Carol & Jeffrey S. Dover (2009). The Encyclopedia of Skin and Skin Disorders. Infobase Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 9780816075096.

- ^ "Fragrance Info / FAQs". The Fragrance Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Burr, Chandler (2003). The Emperor of Scent: A Story of Perfume, Obsession, and the Last Mystery of the Senses. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50797-3.

- ^ Perfume connoisseurs speak of a fragrance's "sillage", or the discernible trail it leaves in the air when applied. Fortineau, Anne-Dominique (2004). "Chemistry Perfumes Your Daily Life". Journal of Chemical Education.81(1)

- Edwards, Michael (2006). "Fragrances of the World 2006". Crescent House Publishing. ISBN 0-9756097-1-8

- "Fragrance 101: Understanding The Fragrance Pyramid". Blog.lebermuth.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "Coco Mademoiselle from Chanel". Chanel.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Osborne, Grant (1 May 2001). "Interview with Michael Edwards". Basenotes.net. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- Dugan, Holly (14 September 2011). The Ephemeral History of Perfume: Scent and Sense in Early Modern England. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0234-5.

- "Civet suffering". Profumo.it. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Olsen, Andreas; Linda C. Prinsloo; Louis Scott; Anna K. Jägera (November–December 2008). "Hyraceum, the fossilized metabolic product of rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis), shows GABA-benzodiazepine receptor affinity" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011.

- "Iso E Super". International Flavors & Fragrances. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008.

- "Account Suspended". Topcolognesformen.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Camps, Arcadi Boix (2000). "Perfumery Techniques in Evolution". Allured Pub Corp. ISBN 0-931710-72-3

- Islam, G., Endrissat, N., & Noppeney, C. (2016). Beyond "the Eye" of the Beholder: Scent innovation through analogical reconfiguration. Organization Studies, 0170840615622064. http://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615622064.

- ^ Burr, Chandler (2008). The Perfect Scent: A Year Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris & New York. Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-8037-7.

- Calkin, Robert R. & Jellinek, J. Stephen (1994). "Perfumery: practice and principles". John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-58934-9

- ^ David A. Einhorn; Lesley Portnoy (April 2010), "The Copyrightability of Perfumes: I Smell a Symphony", Intellectual Property Today, archived from the original on 10 March 2014, retrieved 9 March 2014

- One example being Fidji by Guy Laroche — this particular example can be found on Reni.su Archived 15 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kumar P, Caradonna-Graham VM, Gupta S, Cai X, Rao PN, Thompson J (November 1995). "Inhalation challenge effects of perfume scent strips in patients with asthma". Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 75 (5): 429–33. PMID 7583865.

- Frosch PJ, Rastogi SC, Pirker C, et al. (April 2005). "Patch testing with a new fragrance mix – reactivity to the individual constituents and chemical detection in relevant cosmetic products". Contact Derm. 52 (4): 216–25. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00563.x. PMID 15859994. S2CID 5661020.

- Deborah Gushman. "The Nose Knows". Hanahou.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- Apostolidis S, Chandra T, Demirhan I, Cinatl J, Doerr HW, Chandra A (2002). "Evaluation of carcinogenic potential of two nitro-musk derivatives, musk xylene and musk tibetene in a host-mediated in vivo/in vitro assay system". Anticancer Res. 22 (5): 2657–62. PMID 12529978.

- Schmeiser HH, Gminski R, Mersch-Sundermann V (May 2001). "Evaluation of health risks caused by musk ketone". Int J Hyg Environ Health. 203 (4): 293–9. Bibcode:2001IJHEH.203..293S. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00047. PMID 11434209.

- Berenbaum, May (14 June 2010). "Furanocoumarins as potent chemical defenses". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Environmental and Health Assessment of Substances in Household Detergents and Cosmetic Detergent Products Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON CONSUMER PRODUCTS : SCCP" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Gottfried Schmalz; Dorthe Arenholt Bindslev (2008). Biocompatibility of Dental Materials. Springer. ISBN 9783540777823. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- Thomas P. Habif (2009). Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0323080378. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Edward T. Bope; Rick D. Kellerman (2013). Conn's Current Therapy 2014: Expert Consult. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 264. ISBN 9780323225724. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- T. Platts-Mills; Johannes Ring (2006). Allergy in Practice. Springer. p. 35. ISBN 9783540265849. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Jeanne Duus Johansen; Peter J. Frosch; Jean-Pierre Lepoittevin (2010). Contact Dermatitis. Springer. p. 556. ISBN 9783642038273. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- M. H. Beck; S. M. Wilkinson (2010), "Contact Dermatitis: Allergic", Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, vol. 2 (8th ed.), Wiley, p. 26.40

- "Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) - Public Health - European Commission". Ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "OPINION OF THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON COSMETIC PRODUCTS AND NON-FOOD PRODUCTS INTENDED FOR CONSUMERS CONCERNING MUSK XYLENE AND MUSK KETONE" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Schreurs RH, Legler J, Artola-Garicano E, et al. (February 2004). "In vitro and in vivo antiestrogenic effects of polycyclic musks in zebrafish" (PDF). Environ. Sci. Technol. 38 (4): 997–1002. Bibcode:2004EnST...38..997S. doi:10.1021/es034648y. PMID 14998010. S2CID 8660062. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Schreurs RH, Sonneveld E, Jansen JH, Seinen W, van der Burg B (February 2005). "Interaction of polycyclic musks and UV filters with the estrogen receptor (ER), androgen receptor (AR), and progesterone receptor (PR) in reporter gene bioassays". Toxicol. Sci. 83 (2): 264–72. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi035. PMID 15537743.

- "Opinion on hhcb" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "European Union Risk Assessment Report : 1,3,4,6,7,8-HEXAHYDRO-4,6,6,7,8,8-HEXAMETHYLCYCLOPENTA-γ-2-BENZOPYRAN (1,3,4,6,7,8-HEXAHYDRO-4,6,6,7,8,8-HEXAMETHYLIN-DENO[5,6-C]PYRAN - HHCB)". Echa.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks : SCHER Opinion on Risk Assessment Report on 1,3,4,6,7,8-HEXAHYDRO4,6,6,7,8,8-HEXAMETHYLCYCLOPENTA-γ-2-BENZOPYRAN (HHCB) Human Health Part" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "TSCA Work Plan Chemicals - Existing Chemicals - OPPT - US EPA". Epa.gov. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Opinion on ahtn" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Rastogi SC, Bossi R, Johansen JD, et al. (June 2004). "Content of oak moss allergens atranol and chloroatranol in perfumes and similar products". Contact Derm. 50 (6): 367–70. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00379.x. PMID 15274728. S2CID 38375267.

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products (recast) (Consolidated text)

- "standards - IFRA International Fragrance Association - in every sense". Ifraorg.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Duedahl-Olesen L, Cederberg T, Pedersen KH, Højgård A (October 2005). "Synthetic musk fragrances in trout from Danish fish farms and human milk". Chemosphere. 61 (3): 422–31. Bibcode:2005Chmsp..61..422D. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.004. PMID 16182860.

- Peck AM, Linebaugh EK, Hornbuckle KC (September 2006). "Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario Sediment Cores". Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (18): 5629–35. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.5629P. doi:10.1021/es060134y. PMC 2757450. PMID 17007119.

- Directive 2003/15/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 February 2003 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products

- Colton, Sarah, "L'Osmothèque—Preserving The Past To Ensure The Future", Beauty Fashion Archived 15 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Burr, Chandler (2004). "The Emperor of Scent: A True Story of Perfume and Obsession" Random House Publishing. ISBN 978-0-375-75981-9

- Edwards, Michael (1997). "Perfume Legends: French Feminine Fragrances". Crescent House Publishing. ISBN 0-646-27794-4.

- Ellena, Jean-Claude (2022) . Atlas of Perfumed Botany [Atlas de botanique parfumée]. Translated by Erik Butler. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04673-2.

- Klymentiev, Maksym. "Creating Spices for the Mind: The Origins of Modern Western Perfumery". The Senses and Society. Vol. 9, 2014, issue 2.

- Moran, Jan (2000). "Fabulous Fragrances II: A Guide to Prestige Perfumes for Women and Men". Crescent House Publishing. ISBN 0-9639065-4-2.

- Turin, Luca (2006). "The Secret of Scent". Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-21537-8.

- Stamelman, Richard: "Perfume – Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin". Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-2832-6. A cultural history of fragrance from 1750 to the present day.

- Süskind, Patrick (2006). "Perfume: The Story of a Murderer". Vintage Publishing (English edition). ISBN 978-0-307-27776-3. A novel of perfume, obsession and serial murder. Also released as a movie with same name in 2006.

External links

Media related to Perfumes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Perfumes at Wikimedia Commons- IFRA: International Fragrance Association

- The Fragrance Foundation "FiFi"

- The British Society of Perfumers

| Perfumes | |

|---|---|

| Overview | |

| Types | |

| Ingredients | |

| Science | |

| Professions | |

| Organizations | |

| People | |

| Companies | |