In programming and information security, a buffer overflow or buffer overrun is an anomaly whereby a program writes data to a buffer beyond the buffer's allocated memory, overwriting adjacent memory locations.

Buffers are areas of memory set aside to hold data, often while moving it from one section of a program to another, or between programs. Buffer overflows can often be triggered by malformed inputs; if one assumes all inputs will be smaller than a certain size and the buffer is created to be that size, then an anomalous transaction that produces more data could cause it to write past the end of the buffer. If this overwrites adjacent data or executable code, this may result in erratic program behavior, including memory access errors, incorrect results, and crashes.

Exploiting the behavior of a buffer overflow is a well-known security exploit. On many systems, the memory layout of a program, or the system as a whole, is well defined. By sending in data designed to cause a buffer overflow, it is possible to write into areas known to hold executable code and replace it with malicious code, or to selectively overwrite data pertaining to the program's state, therefore causing behavior that was not intended by the original programmer. Buffers are widespread in operating system (OS) code, so it is possible to make attacks that perform privilege escalation and gain unlimited access to the computer's resources. The famed Morris worm in 1988 used this as one of its attack techniques.

Programming languages commonly associated with buffer overflows include C and C++, which provide no built-in protection against accessing or overwriting data in any part of memory and do not automatically check that data written to an array (the built-in buffer type) is within the boundaries of that array. Bounds checking can prevent buffer overflows, but requires additional code and processing time. Modern operating systems use a variety of techniques to combat malicious buffer overflows, notably by randomizing the layout of memory, or deliberately leaving space between buffers and looking for actions that write into those areas ("canaries").

Technical description

A buffer overflow occurs when data written to a buffer also corrupts data values in memory addresses adjacent to the destination buffer due to insufficient bounds checking. This can occur when copying data from one buffer to another without first checking that the data fits within the destination buffer.

Example

Further information on stack-based overflows: Stack buffer overflowIn the following example expressed in C, a program has two variables which are adjacent in memory: an 8-byte-long string buffer, A, and a two-byte big-endian integer, B.

char A = ""; unsigned short B = 1979;

Initially, A contains nothing but zero bytes, and B contains the number 1979.

| variable name | A | B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | 1979 | |||||||||

| hex value | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 07 | BB |

Now, the program attempts to store the null-terminated string "excessive" with ASCII encoding in the A buffer.

strcpy(A, "excessive");

"excessive" is 9 characters long and encodes to 10 bytes including the null terminator, but A can take only 8 bytes. By failing to check the length of the string, it also overwrites the value of B:

| variable name | A | B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | 'e' | 'x' | 'c' | 'e' | 's' | 's' | 'i' | 'v' | 25856 | |

| hex | 65 | 78 | 63 | 65 | 73 | 73 | 69 | 76 | 65 | 00 |

B's value has now been inadvertently replaced by a number formed from part of the character string. In this example "e" followed by a zero byte would become 25856.

Writing data past the end of allocated memory can sometimes be detected by the operating system to generate a segmentation fault error that terminates the process.

To prevent the buffer overflow from happening in this example, the call to strcpy could be replaced with strlcpy, which takes the maximum capacity of A (including a null-termination character) as an additional parameter and ensures that no more than this amount of data is written to A:

strlcpy(A, "excessive", sizeof(A));

When available, the strlcpy library function is preferred over strncpy which does not null-terminate the destination buffer if the source string's length is greater than or equal to the size of the buffer (the third argument passed to the function). Therefore A may not be null-terminated and cannot be treated as a valid C-style string.

Exploitation

The techniques to exploit a buffer overflow vulnerability vary by architecture, operating system, and memory region. For example, exploitation on the heap (used for dynamically allocated memory), differs markedly from exploitation on the call stack. In general, heap exploitation depends on the heap manager used on the target system, while stack exploitation depends on the calling convention used by the architecture and compiler.

Stack-based exploitation

Main article: Stack buffer overflowThere are several ways in which one can manipulate a program by exploiting stack-based buffer overflows:

- Changing program behavior by overwriting a local variable located near the vulnerable buffer on the stack;

- By overwriting the return address in a stack frame to point to code selected by the attacker, usually called the shellcode. Once the function returns, execution will resume at the attacker's shellcode;

- By overwriting a function pointer or exception handler to point to the shellcode, which is subsequently executed;

- By overwriting a local variable (or pointer) of a different stack frame, which will later be used by the function that owns that frame.

The attacker designs data to cause one of these exploits, then places this data in a buffer supplied to users by the vulnerable code. If the address of the user-supplied data used to affect the stack buffer overflow is unpredictable, exploiting a stack buffer overflow to cause remote code execution becomes much more difficult. One technique that can be used to exploit such a buffer overflow is called "trampolining". Here, an attacker will find a pointer to the vulnerable stack buffer and compute the location of their shellcode relative to that pointer. The attacker will then use the overwrite to jump to an instruction already in memory which will make a second jump, this time relative to the pointer. That second jump will branch execution into the shellcode. Suitable instructions are often present in large code. The Metasploit Project, for example, maintains a database of suitable opcodes, though it lists only those found in the Windows operating system.

Heap-based exploitation

Main article: Heap overflowA buffer overflow occurring in the heap data area is referred to as a heap overflow and is exploitable in a manner different from that of stack-based overflows. Memory on the heap is dynamically allocated by the application at run-time and typically contains program data. Exploitation is performed by corrupting this data in specific ways to cause the application to overwrite internal structures such as linked list pointers. The canonical heap overflow technique overwrites dynamic memory allocation linkage (such as malloc meta data) and uses the resulting pointer exchange to overwrite a program function pointer.

Microsoft's GDI+ vulnerability in handling JPEGs is an example of the danger a heap overflow can present.

Barriers to exploitation

Manipulation of the buffer, which occurs before it is read or executed, may lead to the failure of an exploitation attempt. These manipulations can mitigate the threat of exploitation, but may not make it impossible. Manipulations could include conversion to upper or lower case, removal of metacharacters and filtering out of non-alphanumeric strings. However, techniques exist to bypass these filters and manipulations, such as alphanumeric shellcode, polymorphic code, self-modifying code, and return-to-libc attacks. The same methods can be used to avoid detection by intrusion detection systems. In some cases, including where code is converted into Unicode, the threat of the vulnerability has been misrepresented by the disclosers as only Denial of Service when in fact the remote execution of arbitrary code is possible.

Practicalities of exploitation

In real-world exploits there are a variety of challenges which need to be overcome for exploits to operate reliably. These factors include null bytes in addresses, variability in the location of shellcode, differences between environments, and various counter-measures in operation.

NOP sled technique

Main article: NOP slide

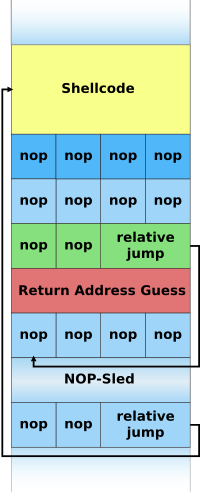

A NOP-sled is the oldest and most widely known technique for exploiting stack buffer overflows. It solves the problem of finding the exact address of the buffer by effectively increasing the size of the target area. To do this, much larger sections of the stack are corrupted with the no-op machine instruction. At the end of the attacker-supplied data, after the no-op instructions, the attacker places an instruction to perform a relative jump to the top of the buffer where the shellcode is located. This collection of no-ops is referred to as the "NOP-sled" because if the return address is overwritten with any address within the no-op region of the buffer, the execution will "slide" down the no-ops until it is redirected to the actual malicious code by the jump at the end. This technique requires the attacker to guess where on the stack the NOP-sled is instead of the comparatively small shellcode.

Because of the popularity of this technique, many vendors of intrusion prevention systems will search for this pattern of no-op machine instructions in an attempt to detect shellcode in use. A NOP-sled does not necessarily contain only traditional no-op machine instructions. Any instruction that does not corrupt the machine state to a point where the shellcode will not run can be used in place of the hardware assisted no-op. As a result, it has become common practice for exploit writers to compose the no-op sled with randomly chosen instructions which will have no real effect on the shellcode execution.

While this method greatly improves the chances that an attack will be successful, it is not without problems. Exploits using this technique still must rely on some amount of luck that they will guess offsets on the stack that are within the NOP-sled region. An incorrect guess will usually result in the target program crashing and could alert the system administrator to the attacker's activities. Another problem is that the NOP-sled requires a much larger amount of memory in which to hold a NOP-sled large enough to be of any use. This can be a problem when the allocated size of the affected buffer is too small and the current depth of the stack is shallow (i.e., there is not much space from the end of the current stack frame to the start of the stack). Despite its problems, the NOP-sled is often the only method that will work for a given platform, environment, or situation, and as such it is still an important technique.

The jump to address stored in a register technique

The "jump to register" technique allows for reliable exploitation of stack buffer overflows without the need for extra room for a NOP-sled and without having to guess stack offsets. The strategy is to overwrite the return pointer with something that will cause the program to jump to a known pointer stored within a register which points to the controlled buffer and thus the shellcode. For example, if register A contains a pointer to the start of a buffer then any jump or call taking that register as an operand can be used to gain control of the flow of execution.

DbgPrint() routine contains the i386 machine opcode for jmp esp.In practice a program may not intentionally contain instructions to jump to a particular register. The traditional solution is to find an unintentional instance of a suitable opcode at a fixed location somewhere within the program memory. Figure E on the left contains an example of such an unintentional instance of the i386 jmp esp instruction. The opcode for this instruction is FF E4. This two-byte sequence can be found at a one-byte offset from the start of the instruction call DbgPrint at address 0x7C941EED. If an attacker overwrites the program return address with this address the program will first jump to 0x7C941EED, interpret the opcode FF E4 as the jmp esp instruction, and will then jump to the top of the stack and execute the attacker's code.

When this technique is possible the severity of the vulnerability increases considerably. This is because exploitation will work reliably enough to automate an attack with a virtual guarantee of success when it is run. For this reason, this is the technique most commonly used in Internet worms that exploit stack buffer overflow vulnerabilities.

This method also allows shellcode to be placed after the overwritten return address on the Windows platform. Since executables are mostly based at address 0x00400000 and x86 is a little endian architecture, the last byte of the return address must be a null, which terminates the buffer copy and nothing is written beyond that. This limits the size of the shellcode to the size of the buffer, which may be overly restrictive. DLLs are located in high memory (above 0x01000000) and so have addresses containing no null bytes, so this method can remove null bytes (or other disallowed characters) from the overwritten return address. Used in this way, the method is often referred to as "DLL trampolining".

Protective countermeasures

Various techniques have been used to detect or prevent buffer overflows, with various tradeoffs. The following sections describe the choices and implementations available.

Choice of programming language

Assembly, C, and C++ are popular programming languages that are vulnerable to buffer overflow in part because they allow direct access to memory and are not strongly typed. C provides no built-in protection against accessing or overwriting data in any part of memory. More specifically, it does not check that data written to a buffer is within the boundaries of that buffer. The standard C++ libraries provide many ways of safely buffering data, and C++'s Standard Template Library (STL) provides containers that can optionally perform bounds checking if the programmer explicitly calls for checks while accessing data. For example, a vector's member function at() performs a bounds check and throws an out_of_range exception if the bounds check fails. However, C++ behaves just like C if the bounds check is not explicitly called. Techniques to avoid buffer overflows also exist for C.

Languages that are strongly typed and do not allow direct memory access, such as COBOL, Java, Eiffel, Python, and others, prevent buffer overflow in most cases. Many programming languages other than C or C++ provide runtime checking and in some cases even compile-time checking which might send a warning or raise an exception, while C or C++ would overwrite data and continue to execute instructions until erroneous results are obtained, potentially causing the program to crash. Examples of such languages include Ada, Eiffel, Lisp, Modula-2, Smalltalk, OCaml and such C-derivatives as Cyclone, Rust and D. The Java and .NET Framework bytecode environments also require bounds checking on all arrays. Nearly every interpreted language will protect against buffer overflow, signaling a well-defined error condition. Languages that provide enough type information to do bounds checking often provide an option to enable or disable it. Static code analysis can remove many dynamic bound and type checks, but poor implementations and awkward cases can significantly decrease performance. Software engineers should carefully consider the tradeoffs of safety versus performance costs when deciding which language and compiler setting to use.

Use of safe libraries

The problem of buffer overflows is common in the C and C++ languages because they expose low level representational details of buffers as containers for data types. Buffer overflows can be avoided by maintaining a high degree of correctness in code that performs buffer management. It has also long been recommended to avoid standard library functions that are not bounds checked, such as gets, scanf and strcpy. The Morris worm exploited a gets call in fingerd.

Well-written and tested abstract data type libraries that centralize and automatically perform buffer management, including bounds checking, can reduce the occurrence and impact of buffer overflows. The primary data types in languages in which buffer overflows are common are strings and arrays. Thus, libraries preventing buffer overflows in these data types can provide the vast majority of the necessary coverage. However, failure to use these safe libraries correctly can result in buffer overflows and other vulnerabilities, and naturally any bug in the library is also a potential vulnerability. "Safe" library implementations include "The Better String Library", Vstr and Erwin. The OpenBSD operating system's C library provides the strlcpy and strlcat functions, but these are more limited than full safe library implementations.

In September 2007, Technical Report 24731, prepared by the C standards committee, was published. It specifies a set of functions that are based on the standard C library's string and IO functions, with additional buffer-size parameters. However, the efficacy of these functions for reducing buffer overflows is disputable. They require programmer intervention on a per function call basis that is equivalent to intervention that could make the analogous older standard library functions buffer overflow safe.

Buffer overflow protection

Main article: Buffer overflow protectionBuffer overflow protection is used to detect the most common buffer overflows by checking that the stack has not been altered when a function returns. If it has been altered, the program exits with a segmentation fault. Three such systems are Libsafe, and the StackGuard and ProPolice gcc patches.

Microsoft's implementation of Data Execution Prevention (DEP) mode explicitly protects the pointer to the Structured Exception Handler (SEH) from being overwritten.

Stronger stack protection is possible by splitting the stack in two: one for data and one for function returns. This split is present in the Forth language, though it was not a security-based design decision. Regardless, this is not a complete solution to buffer overflows, as sensitive data other than the return address may still be overwritten.

This type of protection is also not entirely accurate because it does not detect all attacks. Systems like StackGuard are more centered around the behavior of the attacks, which makes them efficient and faster in comparison to range-check systems.

Pointer protection

Buffer overflows work by manipulating pointers, including stored addresses. PointGuard was proposed as a compiler-extension to prevent attackers from reliably manipulating pointers and addresses. The approach works by having the compiler add code to automatically XOR-encode pointers before and after they are used. Theoretically, because the attacker does not know what value will be used to encode and decode the pointer, one cannot predict what the pointer will point to if it is overwritten with a new value. PointGuard was never released, but Microsoft implemented a similar approach beginning in Windows XP SP2 and Windows Server 2003 SP1. Rather than implement pointer protection as an automatic feature, Microsoft added an API routine that can be called. This allows for better performance (because it is not used all of the time), but places the burden on the programmer to know when its use is necessary.

Because XOR is linear, an attacker may be able to manipulate an encoded pointer by overwriting only the lower bytes of an address. This can allow an attack to succeed if the attacker can attempt the exploit multiple times or complete an attack by causing a pointer to point to one of several locations (such as any location within a NOP sled). Microsoft added a random rotation to their encoding scheme to address this weakness to partial overwrites.

Executable space protection

Main article: Executable space protectionExecutable space protection is an approach to buffer overflow protection that prevents execution of code on the stack or the heap. An attacker may use buffer overflows to insert arbitrary code into the memory of a program, but with executable space protection, any attempt to execute that code will cause an exception.

Some CPUs support a feature called NX ("No eXecute") or XD ("eXecute Disabled") bit, which in conjunction with software, can be used to mark pages of data (such as those containing the stack and the heap) as readable and writable but not executable.

Some Unix operating systems (e.g. OpenBSD, macOS) ship with executable space protection (e.g. W^X). Some optional packages include:

Newer variants of Microsoft Windows also support executable space protection, called Data Execution Prevention. Proprietary add-ons include:

- BufferShield

- StackDefender

Executable space protection does not generally protect against return-to-libc attacks, or any other attack that does not rely on the execution of the attackers code. However, on 64-bit systems using ASLR, as described below, executable space protection makes it far more difficult to execute such attacks.

Address space layout randomization

Main article: Address space layout randomizationAddress space layout randomization (ASLR) is a computer security feature that involves arranging the positions of key data areas, usually including the base of the executable and position of libraries, heap, and stack, randomly in a process' address space.

Randomization of the virtual memory addresses at which functions and variables can be found can make exploitation of a buffer overflow more difficult, but not impossible. It also forces the attacker to tailor the exploitation attempt to the individual system, which foils the attempts of internet worms. A similar but less effective method is to rebase processes and libraries in the virtual address space.

Deep packet inspection

Main article: Deep packet inspectionThe use of deep packet inspection (DPI) can detect, at the network perimeter, very basic remote attempts to exploit buffer overflows by use of attack signatures and heuristics. This technique can block packets that have the signature of a known attack. It was formerly used in situations in which a long series of No-Operation instructions (known as a NOP-sled) was detected and the location of the exploit's payload was slightly variable.

Packet scanning is not an effective method since it can only prevent known attacks and there are many ways that a NOP-sled can be encoded. Shellcode used by attackers can be made alphanumeric, metamorphic, or self-modifying to evade detection by heuristic packet scanners and intrusion detection systems.

Testing

Checking for buffer overflows and patching the bugs that cause them helps prevent buffer overflows. One common automated technique for discovering them is fuzzing. Edge case testing can also uncover buffer overflows, as can static analysis. Once a potential buffer overflow is detected it should be patched. This makes the testing approach useful for software that is in development, but less useful for legacy software that is no longer maintained or supported.

History

Buffer overflows were understood and partially publicly documented as early as 1972, when the Computer Security Technology Planning Study laid out the technique: "The code performing this function does not check the source and destination addresses properly, permitting portions of the monitor to be overlaid by the user. This can be used to inject code into the monitor that will permit the user to seize control of the machine." Today, the monitor would be referred to as the kernel.

The earliest documented hostile exploitation of a buffer overflow was in 1988. It was one of several exploits used by the Morris worm to propagate itself over the Internet. The program exploited was a service on Unix called finger. Later, in 1995, Thomas Lopatic independently rediscovered the buffer overflow and published his findings on the Bugtraq security mailing list. A year later, in 1996, Elias Levy (also known as Aleph One) published in Phrack magazine the paper "Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit", a step-by-step introduction to exploiting stack-based buffer overflow vulnerabilities.

Since then, at least two major internet worms have exploited buffer overflows to compromise a large number of systems. In 2001, the Code Red worm exploited a buffer overflow in Microsoft's Internet Information Services (IIS) 5.0 and in 2003 the SQL Slammer worm compromised machines running Microsoft SQL Server 2000.

In 2003, buffer overflows present in licensed Xbox games have been exploited to allow unlicensed software, including homebrew games, to run on the console without the need for hardware modifications, known as modchips. The PS2 Independence Exploit also used a buffer overflow to achieve the same for the PlayStation 2. The Twilight hack accomplished the same with the Wii, using a buffer overflow in The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess.

See also

- Billion laughs

- Buffer over-read

- Coding conventions

- Computer security

- End-of-file

- Heap overflow

- Ping of death

- Port scanner

- Return-to-libc attack

- Safety-critical system

- Security-focused operating system

- Self-modifying code

- Software quality

- Shellcode

- Stack buffer overflow

- Uncontrolled format string

References

- R. Shirey (August 2007). Internet Security Glossary, Version 2. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4949. RFC 4949. Informational.

- "CORE-2007-0219: OpenBSD's IPv6 mbufs remote kernel buffer overflow". Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- "Modern Overflow Targets" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- "The Metasploit Opcode Database". Archived from the original on 12 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- "Microsoft Technet Security Bulletin MS04-028". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- "Creating Arbitrary Shellcode In Unicode Expanded Strings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-01-05. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- Vangelis (2004-12-08). "Stack-based Overflow Exploit: Introduction to Classical and Advanced Overflow Technique". Wowhacker via Neworder. Archived from the original (text) on August 18, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Balaban, Murat. "Buffer Overflows Demystified" (text). Enderunix.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Akritidis, P.; Evangelos P. Markatos; M. Polychronakis; Kostas D. Anagnostakis (2005). "STRIDE: Polymorphic Sled Detection through Instruction Sequence Analysis." (PDF). Proceedings of the 20th IFIP International Information Security Conference (IFIP/SEC 2005). IFIP International Information Security Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Klein, Christian (September 2004). "Buffer Overflow" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Shah, Saumil (2006). "Writing Metasploit Plugins: from vulnerability to exploit" (PDF). Hack In The Box. Kuala Lumpur. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 2A: Instruction Set Reference, A-M (PDF). Intel Corporation. May 2007. pp. 3–508. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-29.

- Alvarez, Sergio (2004-09-05). "Win32 Stack BufferOverFlow Real Life Vuln-Dev Process" (PDF). IT Security Consulting. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ukai, Yuji; Soeder, Derek; Permeh, Ryan (2004). "Environment Dependencies in Windows Exploitation". BlackHat Japan. Japan: eEye Digital Security. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- ^ https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Buffer_OverflowsBuffer Overflows article on OWASP Archived 2016-08-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "vector::at - C++ Reference". Cplusplus.com. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- "Archived copy". wiretap.area.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2001. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The Better String Library".

- "The Vstr Homepage". Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- "The Erwin Homepage". Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- International Organization for Standardization (2007). "Information technology – Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces – Extensions to the C library – Part 1: Bounds-checking interfaces". ISO Online Browsing Platform.

- "CERT Secure Coding Initiative". Archived from the original on December 28, 2012. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- "Libsafe at FSF.org". Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- "StackGuard: Automatic Adaptive Detection and Prevention of Buffer-Overflow Attacks by Cowan et al" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- "ProPolice at X.ORG". Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- "Bypassing Windows Hardware-enforced Data Execution Prevention". Archived from the original on 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- Lhee, Kyung-Suk; Chapin, Steve J. (2003-04-25). "Buffer overflow and format string overflow vulnerabilities". Software: Practice and Experience. 33 (5): 423–460. doi:10.1002/spe.515. ISSN 0038-0644.

- "12th USENIX Security Symposium – Technical Paper". www.usenix.org. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Protecting against Pointer Subterfuge (Kinda!)". msdn.com. Archived from the original on 2010-05-02. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "USENIX - The Advanced Computing Systems Association" (PDF). www.usenix.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Protecting against Pointer Subterfuge (Redux)". msdn.com. Archived from the original on 2009-12-19. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "PaX: Homepage of the PaX team". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "KernelTrap.Org". Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Openwall Linux kernel patch 2.4.34-ow1". Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Microsoft Technet: Data Execution Prevention". Archived from the original on 2006-06-22. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- "BufferShield: Prevention of Buffer Overflow Exploitation for Windows". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "NGSec Stack Defender". Archived from the original on 2007-05-13. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "PaX at GRSecurity.net". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "The Exploitant - Security info and tutorials". Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- Larochelle, David; Evans, David (13 August 2001). "Statically Detecting Likely Buffer Overflow Vulnerabilities". USENIX Security Symposium. 32.

- "Computer Security Technology Planning Study" (PDF). p. 61. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ""A Tour of The Worm" by Donn Seeley, University of Utah". Archived from the original on 2007-05-20. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Bugtraq security mailing list archive". Archived from the original on 2007-09-01. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ""Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit" by Aleph One". Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- "eEye Digital Security". Archived from the original on 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Microsoft Technet Security Bulletin MS02-039". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Hacker breaks Xbox protection without mod-chip". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

External links

- "Discovering and exploiting a remote buffer overflow vulnerability in an FTP server" by Raykoid666

- "Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit" by Aleph One

- Gerg, Isaac (2005-05-02). "An Overview and Example of the Buffer-Overflow Exploit" (PDF). IAnewsletter. 7 (4). Information Assurance Technology Analysis Center: 16–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- CERT Secure Coding Standards

- CERT Secure Coding Initiative

- Secure Coding in C and C++

- SANS: inside the buffer overflow attack

- "Advances in adjacent memory overflows" by Nomenumbra

- A Comparison of Buffer Overflow Prevention Implementations and Weaknesses

- More Security Whitepapers about Buffer Overflows

- Chapter 12: Writing Exploits III from Sockets, Shellcode, Porting & Coding: Reverse Engineering Exploits and Tool Coding for Security Professionals by James C. Foster (ISBN 1-59749-005-9). Detailed explanation of how to use Metasploit to develop a buffer overflow exploit from scratch.

- Computer Security Technology Planning Study, James P. Anderson, ESD-TR-73-51, ESD/AFSC, Hanscom AFB, Bedford, MA 01731 (October 1972)

- "Buffer Overflows: Anatomy of an Exploit" by Nevermore

- Secure Programming with GCC and GLibc Archived 2008-11-21 at the Wayback Machine (2008), by Marcel Holtmann

- "Criação de Exploits com Buffer Overflor – Parte 0 – Um pouco de teoria " (2018), by Helvio Junior (M4v3r1ck)