Pomo traditional narratives include myths, legends, tales, and oral histories preserved by the Pomo people of the North Coast region of northwestern California.

Pomo oral literature reflects the transitional position of Atsugewi culture between central California, Northwest Coast, Plateau, and Great Basin regions.

Origin

The Pomo are a group of Natives who originate in California. They descend from the Hokan speaking people of the Sonoma County region. Their territory lying in North California, centered in the Russian River valley on the boarder of the Pacific Coast, stretching out a 50 to 100 mile radius. Present day San Francisco is where they settled for more than ten thousand years before the initial contact with the Europeans. Once settled in 1850 the U.S government pushed out the Pomo and forced them onto reservations so they could take the land and give it to the new incoming Americans.

Creation stories

There are multiple creation stories told in different variants on the same topic. Some tribes have different traditional stories specific to each tribe but some also have similar ones and share the same stories. The Coyote, fox and birds reign supreme when it comes to the creation of things in the Pomo culture.

Creation of the sun and moon

The Southern Pomo Gallinomero legend about the origin of light is that in the beginning of time there was nothing but pure darkness, no sun and no moon. There were animals yet there was no light so they could not get around easily. The coyote and the hawk were the ones who ended up creating the sun and moon which granted light on the earth. To do this Coyote reached into a swamp and found dry tulle seeds, with these he made a ball out of it and gave the ball to Hawk. From here, Hawk gathered up some flints and flew into the sky with the ball where he send the it whirling around the world. This became the sun. Still however, the nights remained dark so this process repeated with Coyote gathering the seed and Hawk flying into the sky to send it off. However this second bundle had reeds which were damp so it did not burn as well as the first and this is why the moon does not give off as much light as the sun.

Creation of the ocean

The creation of the ocean is a tale told by the Kashaya Pomo people, passed down orally throughout generations. When the Coyote had created the ocean, at the time there were no human beings yet only animals. These animals however, spoke their language and acted as people would today. These animal people were given different languages and sent to different places to live by the Coyote, which is why Indians in different places speak differently. One day when the Coyote was traveling, the place that he had gone to was burning hot and without water so he began to dig with manzanita stick in search of water. At first, there didn't seem to be any water but after a while of digging it began to look like there was some water there. Eventually, after digging deep down, water began to shoot up so high he felt it would reach the sky. The Coyote then ran up a nearby hill in order to see what had happened, at a distance he could see that the land began to fill up completely with water. After becoming a great body of water, Coyote decided to name it the ocean. The belief is that the ocean tastes salty because there had been ashes left there after he burned grass (in order to lure grasshoppers out so that he could eat them). While looking over the water, Coyote saw how still it was, almost like a lake without waves, so he took a stick and waved in wave like motions shouting at it to move. The water moved up and down and splashed and suddenly it lifted up in big waves and broke out onto the rocks. Wave after wave followed until the whole ocean began to move as it is to this very day. Coyote then took his stick out again and marked out a line in the earth in order to set a limit for how far the water could go, setting its boundaries by telling "Go only this far forever". After making the ocean and decided it looked good he made food in the ocean so that people could come to it and gather it. He took different things from the earth and threw them each into the ocean, naming them as he threw them and it becoming what he said it would. First, he made the biggest animal in the ocean, the whale, by throwing down a large log and saying " this will be a whale", and that's what it became. And when these logs were thrown into the ocean to create whales it made the water shoot up which is why whales can shoot out water today. This process repeated, of the Coyote picking up different logs from different trees making all the animals till the ocean was full of them. After making whales and many other things he gave them instructions and rules to live by, placing them in different parts of the ocean and making that their home. Coyote then gathered different plants and threw them into the ocean to grow, and continued to gather different things for the ocean. Coyote made all these things in the ocean for the people to have.

Beliefs

The Coyote or 'Kunula' was an important mythological figure in the Pomo tribe who was considered a powerful entity. Coyotes are considered to be the creator and ancestor god of the Pomo. Coyotes are seen as intelligent, crafty, and stealthy. In American Indian tribes the coyotes vary throughout the different tribes, in the case of the Pomo tribe it was seen as a hero who created the sun and moon as well as the people.World Order

Spirits and entities

In the Pomo tradition, the world contained six supernatural beings who lived at each end of the world, north, south, east and west, as well as one in the sky and one underneath in the earth.

- The Guksu or Kuksu for some different languages, was a supernatural being who lived at the southern end of the world. The word guksu meant a large mosquito like creature locally known as the 'gallinipper'. This being was the same size as a normal sized human being and had a long, sharp red nose. For ceremonies those impersonating the Guksu would paint their bodies black, red, or white and black, and wear large feathery headdresses on their heads.

- The Calnis lived at the eastern part of the world and was often associated with Guksu during ceremonial dances for he was also human form. During these ceremonies when people would impersonate him during the dances they would paint themselves entirely black, carried around a black staff, and wore a cape made of feathers that went over their face.

- The Suupadax lived at the northern end of the world.

- The Xa-matutsi lived at the western end of the world and was associated with the Pacific Ocean, because the Pacific Ocean lied on the western end of the Pomo territory ,the Xa-matutsi was a very important part of their mythology since they believed that the world was bound together by water on the west.

- The Kali-matutsi word is associated with 'sky occupation' since it resided in the sky and heavens.

- The Kai-matutsi word is associated with 'earth occupation', for it lives in the earth below.

It was believed that these spirits lived in their respective ends of the world in sweat houses. Sometimes these being would act out and kill men, but if treated nicely and properly then they would be kind.

Kuksu religion

The Pomo people practiced shamanism, one of its forms taking place as the Kuksu religion, practiced by the Pomo throughout Central and Northern California. The most common and traditional Pomo religion was involving the Kuksu cult which was a set of beliefs as well as practices ranging from dances and rituals where they would dress in their costumes and traditional wear. They would also take part in the impersonation of spirits, as well as ceremonies for their mythological figures such as the coyote. These ceremonies were held annually or for certain occasions, some of which are still held today. In May they would have the strawberry festival in order to bless the fruits upcoming in the year. Following this, in summer they would have a four night festival of sacred dances which ended on the fourth of July when they would have a feast. Then in fall they would have an acorn festival and then another dance later in the winter. The Pomo had a wide variety of games and sports that they would play, but the sport that they were the most passionate about was a hand game where they would hold a bone and the opponent would have to guess which hand it was in. For the Pomo, Kuksu was personified as a spirit not as much as a set belief and way of life compared to the other tribes that also practiced the Kuksu religion. The Kuksu name was used for their supernatural red-beaked being who lived on the southern end of the world. The main Kuksu specialty was healing and attending to the sick, because of this, they named ceremonies after him and during these ceremonies there would be a medicine man who was considered to be the Kuksu.

Story of the afterlife

For the Gallinomero, or the Southern Pomo, mourning ceremonies were seen as a way to allow the passage and intervention of lost ones into the spirit world. All of the Pomo believed in the afterlife and stressed the importance of having a sacred Indian name from the ancestral line so that upon reaching the afterworld, ancestors would be able to greet each other upon arrival. Those mourning their lost ones would gather up their ashes and then scatter them in the air, which they referred to as going to the Happy Western Land beyond the Big Water, for those who were considered to be good people during their lives. However, those considered to have been bad people would go to an Island in the Bitter Waters, which was cold and without food or drink and isolated from others. Once in their respective places, this is where they would live forever. At first the deceased were cremated up until about 1870 when they began to bury them. The loved ones of the deceased would bring gifts to be buried or burned with the dead, such as beads, baskets, robes, etc. The homes and belongings of the deceased would also be burned in order to prevent the ghosts from lingering around the objects.

See also: Traditional narratives (Native California) and Pomo mythologyExternal links

Pomo Narratives

- The Northern California Indians, in Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, No VI by Stephen Powers (1872), pp. 498–507.

- Myths and Legends of California and the Old Southwest by Katharine Berry Judson (1912)

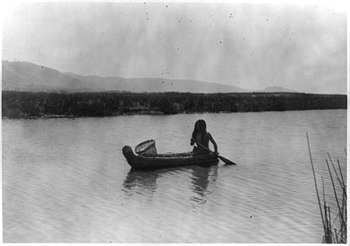

- The North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis (1924)

Sources for Pomo narratives

- Angulo, Jaime de. 1935. "Pomo Creation Myth". Journal of American Folklore 48:203-262. (Eastern Pomo myth collected from W. Galganal Benson.)

- Angulo, Jaime de, and Lucy S. Freeland. 1928. "Miwok and Pomo Myths". Journal of American Folklore 41:232-253. (Myth versions from two Lake Miwok, one Eastern Pomo, and one Southeastern Pomo; Miwok and Pomo versions were reportedly almost identical.)

- Barrett, Samuel A. 1906. "A Composite Myth of the Pomo Indians". Journal of American Folklore 19:37-51. (Theft of Fire myth obtained in 1904, with commentary.)

- Barrett, Samuel A. 1917. "Pomo Bear Doctors". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 12:443-465. Berkeley. (Eastern Pomo myth about the origin of bear shamans, pp. 445–451.)

- Barrett, Samuel A. 1933. Pomo Myths. Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee Bulletin No. 15. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (Numerous myths, including Earth Diver, Theft of Fire, Orpheus, and Bear and Fawns, along with a detailed framework for comparisons.)

- Curtis, Edward S. 1907–1930. The North American Indian. 20 vols. Plimpton Press, Norwood, Massachusetts. (Four myths collected from San Diego (eastern Pomo), Sam Cowan (southern), Jim Ford (northern), and Tom Connor (central), vol. 14, pp. 170–173.)

- Erdoes, Richard, and Alfonso Ortiz. 1984. American Indian Myths and Legends. Pantheon Books, New York. (Retelling of a narrative from Barrett 1933, pp. 397–398.)

- Gifford, Edward Winslow, and Gwendoline Harris Block. 1930. California Indian Nights. Arthur H. Clark, Glendale, California. (One previously published narrative, pp. 287–296.)

- Judson, Katharine Berry. 1912. Myths and Legends of California and the Old Southwest. A. C. McClurg, Chicago. (Three myths, pp. 47, 63, 192.)

- Kroeber, A. L. 1911. "The Languages of the Coast of California North of San Francisco". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 9:273-435. Berkeley. (Includes a Pomo myth, pp. 343–346.)

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C. (A brief note on mythology, pp. 270–271.)

- Loeb, Edwin M. 1926. "The Creator Concept among the Indians of North Central California". American Anthropologist 28:467-493. (Pomo creation myths, including Orpheus.)

- Loeb, Edwin M. 1932. "The Western Kuksu Cult". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 33:1-137. Berkeley. (Note on Northern Pomo mythology, pp. 3–4.)

- Luthin, Herbert W. 2002. Surviving through the Days: A California Indian Reader. University of California Press, Berkeley. (Three Eastern, Southern, and Cache Creek Pomo narratives collected in 1930, 1940, and 1988, pp. 260–333.)

- Margolin, Malcolm. 1993. The Way We Lived: California Indian Stories, Songs, and Reminiscences. First edition 1981. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California. (Three myths, pp. 69–71, 93-94, 126-129, from Angulo and Benson 1932, Barrett 1933, and Oswalt 1964.)

- McLendon, Sally. 1978. "Coyote and the Ground Squirrels (Eastern Pomo)". In Coyote Stories, edited by William Bright, pp. 87–111. International Journal of American Linguistics Native American Texts Series No. 1. University of Chicago Press. (Narrated by Ralph Holder in 1975.)

- Oswalt, Robert L. 1957. Kashaya Texts. University of California Publications in Linguistics No. 36. Berkeley. (Narratives, including Bear and Fawns, collected in 1957-1961.)

- Powers, Stephen. 1877. Tribes of California. Contributions to North American Ethnology, vol. 3. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. Reprinted with an introduction by Robert F. Heizer in 1976, University of California Press, Berkeley. (Three brief narratives, pp. 162, 171-172, 182-183.)

References

- "California Indian Languages: Hokan Tribes". CA State Parks. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- Williams, Rob (2022-10-19). "Three Native American Creation Myths". Medium. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- "Origin of light - A Gallinomero Legend". www.firstpeople.us. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "The Kashaya Pomo people lived on these lands which they called Mettini for thousands of years". 2008-12-03. Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- "Native American Indian Coyote Legends, Meaning and Symbolism from the Myths of Many Tribes". www.native-languages.org. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- Estes, Roberta (2012-12-08). "Pomo Indians". Native Heritage Project. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- https://hermosillopomo.weebly.com/

- Estes, Roberta (2012-12-08). "Pomo Indians". Native Heritage Project. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "Kuksu cult | California Indian religion | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- "The Spirit Land - A Gallinomero Legend". www.firstpeople.us. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

| Traditional narratives of Indigenous Californians | |

|---|---|

|