In mathematics, potential flow around a circular cylinder is a classical solution for the flow of an inviscid, incompressible fluid around a cylinder that is transverse to the flow. Far from the cylinder, the flow is unidirectional and uniform. The flow has no vorticity and thus the velocity field is irrotational and can be modeled as a potential flow. Unlike a real fluid, this solution indicates a net zero drag on the body, a result known as d'Alembert's paradox.

Mathematical solution

A cylinder (or disk) of radius R is placed in a two-dimensional, incompressible, inviscid flow. The goal is to find the steady velocity vector V and pressure p in a plane, subject to the condition that far from the cylinder the velocity vector (relative to unit vectors i and j) is:

where U is a constant, and at the boundary of the cylinder

where n̂ is the vector normal to the cylinder surface. The upstream flow is uniform and has no vorticity. The flow is inviscid, incompressible and has constant mass density ρ. The flow therefore remains without vorticity, or is said to be irrotational, with ∇ × V = 0 everywhere. Being irrotational, there must exist a velocity potential φ:

Being incompressible, ∇ · V = 0, so φ must satisfy Laplace's equation:

The solution for φ is obtained most easily in polar coordinates r and θ, related to conventional Cartesian coordinates by x = r cos θ and y = r sin θ. In polar coordinates, Laplace's equation is (see Del in cylindrical and spherical coordinates):

The solution that satisfies the boundary conditions is

The velocity components in polar coordinates are obtained from the components of ∇φ in polar coordinates:

and

Being inviscid and irrotational, Bernoulli's equation allows the solution for pressure field to be obtained directly from the velocity field:

where the constants U and p∞ appear so that p → p∞ far from the cylinder, where V = U. Using V = V

r + V

θ,

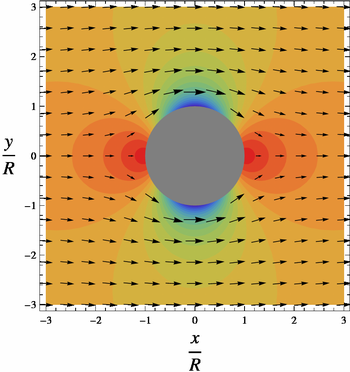

In the figures, the colorized field referred to as "pressure" is a plot of

On the surface of the cylinder, or r = R, pressure varies from a maximum of 1 (shown in the diagram in red) at the stagnation points at θ = 0 and θ = π to a minimum of −3 (shown in blue) on the sides of the cylinder, at θ = π/2 and θ = 3π/2. Likewise, V varies from V = 0 at the stagnation points to V = 2U on the sides, in the low pressure.

Stream function

The flow being incompressible, a stream function can be found such that

It follows from this definition, using vector identities,

Therefore, a contour of a constant value of ψ will also be a streamline, a line tangent to V. For the flow past a cylinder, we find:

Physical interpretation

Laplace's equation is linear, and is one of the most elementary partial differential equations. This simple equation yields the entire solution for both V and p because of the constraint of irrotationality and incompressibility. Having obtained the solution for V and p, the consistency of the pressure gradient with the accelerations can be noted.

The dynamic pressure at the upstream stagnation point has value of 1/2ρU. a value needed to decelerate the free stream flow of speed U. This same value appears at the downstream stagnation point, this high pressure is again needed to decelerate the flow to zero speed. This symmetry arises only because the flow is completely frictionless.

The low pressure on sides on the cylinder is needed to provide the centripetal acceleration of the flow:

where L is the radius of curvature of the flow. But L ≈ R, and V ≈ U. The integral of the equation for centripetal acceleration over a distance Δr ≈ R will thus yield

The exact solution has, for the lowest pressure,

The low pressure, which must be present to provide the centripetal acceleration, will also increase the flow speed as the fluid travels from higher to lower values of pressure. Thus we find the maximum speed in the flow, V = 2U, in the low pressure on the sides of the cylinder.

A value of V > U is consistent with conservation of the volume of fluid. With the cylinder blocking some of the flow, V must be greater than U somewhere in the plane through the center of the cylinder and transverse to the flow.

Comparison with flow of a real fluid past a cylinder

The symmetry of this ideal solution has a stagnation point on the rear side of the cylinder, as well as on the front side. The pressure distribution over the front and rear sides are identical, leading to the peculiar property of having zero drag on the cylinder, a property known as d'Alembert's paradox. Unlike an ideal inviscid fluid, a viscous flow past a cylinder, no matter how small the viscosity, will acquire a thin boundary layer adjacent to the surface of the cylinder. Boundary layer separation will occur, and a trailing wake will exist in the flow behind the cylinder. The pressure at each point on the wake side of the cylinder will be lower than on the upstream side, resulting in a drag force in the downstream direction.

Janzen–Rayleigh expansion

Main article: Janzen–Rayleigh expansionThe problem of potential compressible flow over circular cylinder was first studied by O. Janzen in 1913 and by Lord Rayleigh in 1916 with small compressible effects. Here, the small parameter is square of the Mach number , where c is the speed of sound. Then the solution to first-order approximation in terms of the velocity potential is

where is the radius of the cylinder.

Potential flow over a circular cylinder with slight variations

Regular perturbation analysis for a flow around a cylinder with slight perturbation in the configurations can be found in Milton Van Dyke (1975). In the following, ε will represent a small positive parameter and a is the radius of the cylinder. For more detailed analyses and discussions, readers are referred to Milton Van Dyke's 1975 book Perturbation Methods in Fluid Mechanics.

Slightly distorted cylinder

Here the radius of the cylinder is not r = a, but a slightly distorted form r = a(1 − ε sin θ). Then the solution to first-order approximation is

Slightly pulsating circle

Here the radius of the cylinder varies with time slightly so r = a(1 + ε f(t)). Then the solution to first-order approximation is

Flow with slight vorticity

In general, the free-stream velocity U is uniform, in other words ψ = Uy, but here a small vorticity is imposed in the outer flow.

Linear shear

Here a linear shear in the velocity is introduced.

where ε is the small parameter. The governing equation is

Then the solution to first-order approximation is

Parabolic shear

Here a parabolic shear in the outer velocity is introduced.

Then the solution to the first-order approximation is

where χ is the homogeneous solution to the Laplace equation which restores the boundary conditions.

Slightly porous cylinder

Let Cps represent the surface pressure coefficient for an impermeable cylinder:

where ps is the surface pressure of the impermeable cylinder. Now let Cpi be the internal pressure coefficient inside the cylinder, then a slight normal velocity due to the slight porousness is given by

but the zero net flux condition

requires that Cpi = −1. Therefore,

Then the solution to the first-order approximation is

Corrugated quasi-cylinder

If the cylinder has variable radius in the axial direction, the z-axis, r = a (1 + ε sin z/b), then the solution to the first-order approximation in terms of the three-dimensional velocity potential is

where K1(r/b) is the modified Bessel function of the first kind of order one.

See also

References

- ^ Batchelor, George Keith (2000). An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 424. ISBN 9780521663960.

- Acheson, David J. (1990). Elementary Fluid Dynamics. Oxford University Press. p. 130ff. ISBN 9780198596790.

- Babinsky, Holger (November 2003), "How do wings work?", Physics Education, 38 (6): 497, Bibcode:2003PhyEd..38..497B, doi:10.1088/0031-9120/38/6/001, S2CID 1657792

- O. JANZEN, Beitrag zu eincr Theorie der stationaren Stromung kompressibler Flussigkeiten. Phys. Zeits., 14 (1913)

- Rayleigh, L. (1916). I. On the flow of compressible fluid past an obstacle. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 32(187), 1-6.

- ^ Van Dyke, Milton (1975). Perturbation Methods in Fluid Mechanics (Annotated ed.). Stanford, CA: Parabolic Press. ISBN 978-0-915760-01-5.

, where c is the

, where c is the

is the radius of the cylinder.

is the radius of the cylinder.