The business terms push and pull originated in logistics and supply chain management, but are also widely used in marketing and in the hotel distribution business.

Walmart is an example of a company that uses the push vs. pull strategy.

Supply-chain management

Main article: Supply chain managementComplete definition

There are several definitions on the distinction between push and pull strategies. Liberopoulos (2013) identifies three such definitions:

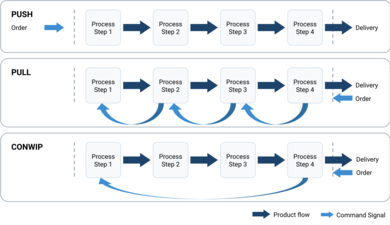

- A pull system initiates production as a reaction to present demand, while a push system initiates production in anticipation of future demand.

- In a pull system, production is triggered by actual demands for finished products, while in a push system, production is initiated independently of demands.

- A pull system is one that explicitly limits the amount of WIP (works in progress) that can be in the system, while a push system has no explicit limit on the amount of WIP that can be in the system.

Other definitions are:

- Push: As stated by Bonney et al. (1999) control information flow is in the same direction of goods flow

- Semi push or Push-pull : Succeeding node makes order request for preceding node. Preceding node reacts by replenishing from stock that is rebuilt every fixed period.

- Pull : Succeeding node makes order request for preceding node. Preceding node reacts by producing the order, which involves all internal operations, and replenishes when finished.

- Semi-pull or pull-push : Succeeding node makes order request for preceding node. Preceding node reacts by replenishing from stock that is rebuilt immediately. There are several levels of semi-pull systems as a node can have stock at several layers in an organization.

Information flow

With a push-based supply chain, products are pushed through the channel, from the production side up to the retailer. The manufacturer sets production at a level in accord with historical ordering patterns from retailers. It takes longer for a push-based supply chain to respond to changes in demand, which can result in overstocking or bottlenecks and delays (the bullwhip effect), unacceptable service levels and product obsolescence.

In a pull-based supply chain, procurement, production and distribution are demand-driven rather than to forecast. However, a pull strategy does not always require make to order production. Toyota Motors Manufacturing is frequently used as an example of pull production, yet do not typically produce to order. They follow the "supermarket model" where limited inventory is kept on hand and is replenished as it is consumed. In Toyota's case, Kanban cards are used to signal the need to replenish inventory.

A supply chain is almost always a combination of both push and pull, where the interface between the push-based stages and the pull-based stages is sometimes known as the push–pull boundary. However, because of the subtle difference between pull production and make-to-order production, a more accurate name for this may be the customer order decoupling point. An example of this is Dell's build to order supply chain. Inventory levels of individual components are determined by forecasting general demand, but final assembly is in response to a specific customer request. The decoupling point would then be at the beginning of the assembly line.

- Applied to that portion of the supply chain where demand uncertainty is relatively small

- Production and distribution decisions are based on long term forecasts

- Based on past orders received from retailer's warehouse (may lead to bullwhip effect)

- Inability to meet changing demand patterns

- Large and variable production batches

- Unacceptable service levels

- Excessive inventories due to the need for large safety stocks

- Less expenditure on advertising than pull strategy

In a marketing pull system, the consumer requests the product and "pulls" it through the delivery channel. An example of this is the car manufacturing company Ford Australia. Ford Australia only produces cars when they have been ordered by customers.

- Applied to that portion of the supply chain where demand uncertainty is high

- Production and distribution are demand driven

- No inventory, response to specific orders

- Point of sale (POS) data comes is helpful when shared with supply chain partners

- Decrease in lead time

- Difficult to implement

Use of pull, push, and hybrid push-pull strategy

Harrison summarized when to use each one of the three supply chain strategies:

- A push based supply chain strategy is usually suggested for products with low demand uncertainty, as the forecast will provide a good indication of what to produce and keep in inventory, and also for products with high importance of economies of scale in reducing costs.

- A pull based supply chain strategy, usually suggested for products with high demand uncertainty and with low importance of economies of scales, which means, aggregation does not reduce cost, and hence, the firm would be willing to manage the supply chain based on realized demand.

- A hybrid push–pull strategy, usually suggested for products which uncertainty in demand is high, while economies of scale are important in reducing production and delivery costs. An example of this strategy is the furniture industry, where production strategy has to follow a pull-based strategy, since it is impossible to make production decisions based on long-term forecasts. However, the distribution strategy needs to take advantage of economies of scale in order to reduce transportation cost, using a push-based strategy.

Examples in push and pull

Hopp and Spearman consider some of the most common systems found in industry and the literature and classify them as either push or pull

- Material requirements planning (MRP) is a push system because releases are made according to a master production schedule without regard to system status. Hence, no prior work in process (WIP) limit exists.

- Classic kanban is a pull system. The number of kanban cards establishes a fixed limit on WIP.

- The classic base stock system is a push system because there is no limit on the amount of work in process in the system. This is because backorders can increase beyond the basestock level.

- Installation stock is also a push system as are echelon stock systems because neither imposes a limit on the number of orders in the system.

- CONstant work in process (CONWIP) is a pull system because it limits WIP via cards similar to kanban. An important difference from kanban from an implementation standpoint is that the cards are line specific rather than part number specific. However, from a push-pull perspective, CONWIP cards limit WIP in the same manner as kanban cards.

- (K, S) systems (proposed by Liberopoulos and Dallery) are pull systems if K <∞ and are push systems otherwise.

- POLCA systems proposed by Suri are pull systems because, like kanban and CONWIP, WIP is limited by cards.

- PAC systems proposed by Buzacott and Shanthikumar are pull systems when the number of process tags (which serve to limit WIP) is less than infinity.

- MRP with a WIP constraint (as suggested by Axsäter and Rosling) is a pull system.

Liberopoulos (2013) also classifies common systems according to different definitions on the distinction between push and pull.

Marketing

An advertising push strategy refers to a situation when a vendor advertises its product to gain audience awareness, while the pull strategy implies the aims to reach audiences which have shown existing interest in the product or information about it. The difference between "push" and "pull" marketing can also be identified by the manner in which the company approaches the lead. If, for example, the company were to send a sales brochure, that would be considered pushing the opportunity toward the lead. If, instead, the company provided a subject matter expert as a speaker for an industry event attended by targeted leads, that could be one tactic used as part of a strategy to pull in a lead by encouraging that lead to seek out the expert in a moment of need for that expertise.

Hotel distribution

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The online world has brought this pull–push decision to the hotel distribution business.

- Push strategies in the hotel distribution business imply that hotel inventory is placed for the distributors or resellers outside the hotel system in one or several extranets that belong to these distributors (online travel agencies, tour operators, and bed banks). The inventory must be therefore updated in these extranets. The hotel servers receive less traffic preventing server crashes but booking must be transferred to the hotel system.

- Pull strategies are based on distributors interfacing with the hotel property management system. In this case the inventory is "pulled" from the hotel (or hotel chain) system. This method provides a much more precise picture of the real availability and saves time loading the bookings but, requires more IT development and a bigger server (dedicated one).

See also

- Supply and demand

- Digital marketing

- Publish/subscribe

- Issue tracking system

- Lean thinking

- Decision making

- Marketing strategy

- Marketing mix modeling

References

- Martin, Michael J.C. (1994). Managing Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Technology-based Firms. Wiley-IEEE. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-471-57219-0.

- Edward G. Hinkelman & Sibylla Putzi (2005). Dictionary of International Trade – Handbook of the Global Trade Community. World Trade Press. ISBN 978-1-885073-72-3.

- Peter, J. Paul; James H. Donnelly (2002). A Preface to Marketing Management. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-07-246658-4.

- Dowling, Grahame Robert (2004). The Art and Science of Marketing. Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-926961-7.

- ^ Liberopoulos, George (2013), Smith, J. MacGregor; Tan, Barış (eds.), "Production Release Control: Paced, WIP-Based or Demand-Driven? Revisiting the Push/Pull and Make-to-Order/Make-to-Stock Distinctions", Handbook of Stochastic Models and Analysis of Manufacturing System Operations, International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, vol. 192, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 211–247, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6777-9_7, ISBN 978-1-4614-6777-9, retrieved 2021-05-02

- J., Ashayeri; R.P., Kampstra (2005). "Demand Driven Distribution: The Logistical Challenges and Opportunities" (Department of Econometrics and Operations Research Tilburg University).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Terry P. Harrison, Hau L. Lee and John J. Neale (2003). The Practice of Supply Chain Management. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24099-2.

- Liberopoulos, George; Dallery, Yves (2002). "Base stock versus WIP cap in single-stage make-to-stock production–inventory systems". IIE Transactions. 34 (7): 627–636. doi:10.1023/A:1014503725395. S2CID 59469286.

- Hopp, Wallace J.; Spearman, Mark L. (2004). "To pull or not to pull: what is the question?". Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 6 (2): 133–148. doi:10.1287/msom.1030.0028.

- Hosbond, Jens Henrik; Skov, Mikael B. (15 November 2007). "Micro mobility marketing: Two cases on location-based supermarket shopping trolleys" (PDF). Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing. 16: 68–77. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jt.5750058 – via Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.