| Part of February Revolution | |

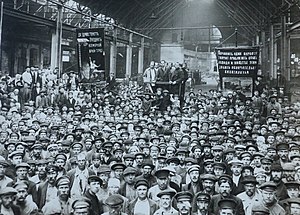

Kirov Plant, Petrograd Kirov Plant, Petrograd | |

| Date | February 18, 1917 |

|---|---|

| Location | Russia |

The Putilov strike of 1917 is the name given to the strike led by the workers of the Putilov Mill (presently the Leningrad Kirov Plant) which was located in then Petrograd, Russia (present-day St. Petersburg). The strike officially began on February 18, 1917 (according to the Julian calendar; March 2 on the Gregorian calendar) and quickly snowballed, sparking larger demonstrations in Petrograd. There were several strikes involving the workers of the Putilov Mill over the years with the first one taking place in 1905, yet this particular strike in 1917 is considered the catalyst which sparked the February Revolution.

Background

World War I had taken its toll on Russia, leading to a decline in the morale of the citizens as well as distrust in the government. Russia, having the largest of all the armies fighting in the war, sent its soldiers to the front ill-prepared. There were armament shortages which forced the soldiers to use the weapons of their fallen comrades which had been killed and some of the soldiers even had to fight bare-foot. The decaying bodies brought about sickness and disease, further infuriating the soldiers. The Tsarist regime had prepared for a war which they believed would only last six months and one they believed they would win virtually untouched. As a result of this ill preparation, the Russian economy suffered greatly and the citizens of Russia began to experience food and necessary goods shortages as well. Petrograd was especially devastated because it was not located near any agriculturally-rich areas and was receiving only one third of its fuel and goods despite its massive population. The prices of food nearly quadrupled and despite this, worker wages remained as they were prior to World War I. The soldiers, workers and peasants were now in severe distress, causing workers to demand higher wages.

The Strike

On February 18, 1917, workers at the Putilov Mill in Petrograd demanded higher wages because of the rising prices of food and goods. When the disgruntled workers began to dispute with the authorities at the mill over the denial of their pay increase, some 20,000 workers were locked out sparking an outrage among other factories in Petrograd. By February 22, in retaliation of the lockout, over 100,000 workers were actively protesting. The next day, on International Women’s Day, women joined the strikes and protests, demanding equal rights as well as others strikers protesting the rationing of bread. By this time, well over 500,000 people were protesting Petrograd for several different reasons. General Khabalov, as ordered by the Tsar, was told to order the troops to fire onto the crowds of protestors, but the soldiers refused. The soldiers instead sided with and joined the protestors as a result of their harsh treatment during the war. As more and more citizens joined the strikes, they became more about economics and politics. The protestors began to express their opposition of the Tsarist regime as well as the war. The majority of the businesses in Petrograd had been closed, ceasing mobilization and daily operations within the city. The strikes, though spontaneous and popular among the citizens, came to a halt on March 4. This series of economic and political strikes lasting from February 22 until March 4, 1917, became known as the February Revolution.

Outcomes

While the city of Petrograd was in disarray, Tsar Nicholas II, was absent from the city and ignorant to the unrest happening there. Upon attempting to return to the city, he realized the severity of what was actually happening, understanding that he was the target of the opposition. He decided to go into hiding, refusing to communicate with anyone. His regime began to disband as its officials began to abandon their positions as well. The Duma advised Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate his throne. He eventually attempted to return to Petrograd, thinking that he would be welcomed, however his train was diverted and it was then that he realized his regime was dismantled. He was again advised to abdicate his throne, which he did. He offered it to Grand Duke Michael, however realizing the magnitude of the disturbances in Petrograd, he refused the throne. The strikes eventually began to ease on March 3 when twelve former members of the Duma formed the Provisional Government led by Prince Georgy Lvov. Several groups such as factory committees formed and many businesses in Petrograd began to have daily meetings. Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies which represented the workers, peasants, and soldiers of Petrograd eventually introduced the eight-hour work day.

References

- 1. Moore, Lyndon and Jakub Kaluzny. “Regime change and debt default: the case of Russia, Austro-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire Following World War One.” Explorations in Economic History 42, no. 2 (2005):237-258

- 2. Grant, Johnathan A. “Putilov at War 1914-1917”. In Big Business in Russia: The Putilov Company in Late Imperial Russia, 1868-1917, 115-116. Pittsburgh, Pa. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999.

- 3. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. S.v. "Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies." Retrieved April 18, 2015 from http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Petrograd+Soviet+of+Workers+and+Soldiers+Deputies

- 4. The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia®. S.v. "The Russian Revolution." Retrieved April 18, 2015 from http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/The+Russian+Revolution 5. Koenker, Diane, and William G. Rosenberg. "The February Revolution and the Mobilization of Labor." In Strikes and Revolution in Russia, 1917, 105. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- 6. Browder, Robert Paul; Kerensky, Aleksandr Fyodorovich (1961). The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: documents. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0023-8.