| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Rhumb line" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In navigation, a rhumb line, rhumb (/rʌm/), or loxodrome is an arc crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, that is, a path with constant azimuth (bearing as measured relative to true north). Navigation on a fixed course (i.e., steering the vessel to follow a constant cardinal direction) would result in a rhumb-line track.

Introduction

Further information: Bearing (navigation) § ArcsThe effect of following a rhumb line course on the surface of a globe was first discussed by the Portuguese mathematician Pedro Nunes in 1537, in his Treatise in Defense of the Marine Chart, with further mathematical development by Thomas Harriot in the 1590s.

A rhumb line can be contrasted with a great circle, which is the path of shortest distance between two points on the surface of a sphere. On a great circle, the bearing to the destination point does not remain constant. If one were to drive a car along a great circle one would hold the steering wheel fixed, but to follow a rhumb line one would have to turn the wheel, turning it more sharply as the poles are approached. In other words, a great circle is locally "straight" with zero geodesic curvature, whereas a rhumb line has non-zero geodesic curvature.

Meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude provide special cases of the rhumb line, where their angles of intersection are respectively 0° and 90°. On a north–south passage the rhumb line course coincides with a great circle, as it does on an east–west passage along the equator.

On a Mercator projection map, any rhumb line is a straight line; a rhumb line can be drawn on such a map between any two points on Earth without going off the edge of the map. But theoretically a loxodrome can extend beyond the right edge of the map, where it then continues at the left edge with the same slope (assuming that the map covers exactly 360 degrees of longitude).

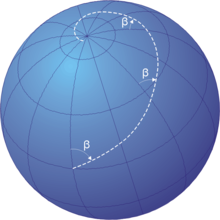

Rhumb lines which cut meridians at oblique angles are loxodromic curves which spiral towards the poles. On a Mercator projection the North Pole and South Pole occur at infinity and are therefore never shown. However the full loxodrome on an infinitely high map would consist of infinitely many line segments between the two edges. On a stereographic projection map, a loxodrome is an equiangular spiral whose center is the north or south pole.

All loxodromes spiral from one pole to the other. Near the poles, they are close to being logarithmic spirals (which they are exactly on a stereographic projection, see below), so they wind around each pole an infinite number of times but reach the pole in a finite distance. The pole-to-pole length of a loxodrome (assuming a perfect sphere) is the length of the meridian divided by the cosine of the bearing away from true north. Loxodromes are not defined at the poles.

Etymology and historical description

The word loxodrome comes from Ancient Greek λοξός loxós: "oblique" + δρόμος drómos: "running" (from δραμεῖν drameîn: "to run"). The word rhumb may come from Spanish or Portuguese rumbo/rumo ("course" or "direction") and Greek ῥόμβος rhómbos, from rhémbein.

The 1878 edition of The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information describes a loxodrome line as:

Loxodrom′ic Line is a curve which cuts every member of a system of lines of curvature of a given surface at the same angle. A ship sailing towards the same point of the compass describes such a line which cuts all the meridians at the same angle. In Mercator's Projection (q.v.) the Loxodromic lines are evidently straight.

A misunderstanding could arise because the term "rhumb" had no precise meaning when it came into use. It applied equally well to the windrose lines as it did to loxodromes because the term only applied "locally" and only meant whatever a sailor did in order to sail with constant bearing, with all the imprecision that that implies. Therefore, "rhumb" was applicable to the straight lines on portolans when portolans were in use, as well as always applicable to straight lines on Mercator charts. For short distances portolan "rhumbs" do not meaningfully differ from Mercator rhumbs, but these days "rhumb" is synonymous with the mathematically precise "loxodrome" because it has been made synonymous retrospectively. As Leo Bagrow states:

the word ('Rhumbline') is wrongly applied to the sea-charts of this period, since a loxodrome gives an accurate course only when the chart is drawn on a suitable projection. Cartometric investigation has revealed that no projection was used in the early charts, for which we therefore retain the name 'portolan'.

Mathematical description

For a sphere of radius 1, the azimuthal angle λ, the polar angle −π/2 ≤ φ ≤ π/2 (defined here to correspond to latitude), and Cartesian unit vectors i, j, and k can be used to write the radius vector r as

Orthogonal unit vectors in the azimuthal and polar directions of the sphere can be written

which have the scalar products

λ̂ for constant φ traces out a parallel of latitude, while φ̂ for constant λ traces out a meridian of longitude, and together they generate a plane tangent to the sphere.

The unit vector

has a constant angle β with the unit vector φ̂ for any λ and φ, since their scalar product is

A loxodrome is defined as a curve on the sphere that has a constant angle β with all meridians of longitude, and therefore must be parallel to the unit vector β̂. As a result, a differential length ds along the loxodrome will produce a differential displacement

where and are the Gudermannian function and its inverse, and is the inverse hyperbolic sine.

With this relationship between λ and φ, the radius vector becomes a parametric function of one variable, tracing out the loxodrome on the sphere:

where

is the isometric latitude.

In the Rhumb line, as the latitude tends to the poles, φ → ±π/2, sin φ → ±1, the isometric latitude arsinh(tan φ) → ± ∞, and longitude λ increases without bound, circling the sphere ever so fast in a spiral towards the pole, while tending to a finite total arc length Δs given by

Connection to the Mercator projection

Let λ be the longitude of a point on the sphere, and φ its latitude. Then, if we define the map coordinates of the Mercator projection as

a loxodrome with constant bearing β from true north will be a straight line, since (using the expression in the previous section)

with a slope

Finding the loxodromes between two given points can be done graphically on a Mercator map, or by solving a nonlinear system of two equations in the two unknowns m = cot β and λ0. There are infinitely many solutions; the shortest one is that which covers the actual longitude difference, i.e. does not make extra revolutions, and does not go "the wrong way around".

The distance between two points Δs, measured along a loxodrome, is simply the absolute value of the secant of the bearing (azimuth) times the north–south distance (except for circles of latitude for which the distance becomes infinite):

where R is one of the earth average radii.

Application

Its use in navigation is directly linked to the style, or projection of certain navigational maps. A rhumb line appears as a straight line on a Mercator projection map.

The name is derived from Old French or Spanish respectively: "rumb" or "rumbo", a line on the chart which intersects all meridians at the same angle. On a plane surface this would be the shortest distance between two points. Over the Earth's surface at low latitudes or over short distances it can be used for plotting the course of a vehicle, aircraft or ship. Over longer distances and/or at higher latitudes the great circle route is significantly shorter than the rhumb line between the same two points. However the inconvenience of having to continuously change bearings while travelling a great circle route makes rhumb line navigation appealing in certain instances.

The point can be illustrated with an east–west passage over 90 degrees of longitude along the equator, for which the great circle and rhumb line distances are the same, at 10,000 kilometres (5,400 nautical miles). At 20 degrees north the great circle distance is 9,254 km (4,997 nmi) while the rhumb line distance is 9,397 km (5,074 nmi), about 1.5% further. But at 60 degrees north the great circle distance is 4,602 km (2,485 nmi) while the rhumb line is 5,000 km (2,700 nmi), a difference of 8.5%. A more extreme case is the air route between New York City and Hong Kong, for which the rhumb line path is 18,000 km (9,700 nmi). The great circle route over the North Pole is 13,000 km (7,000 nmi), or 5+1⁄2 hours less flying time at a typical cruising speed.

Some old maps in the Mercator projection have grids composed of lines of latitude and longitude but also show rhumb lines which are oriented directly towards north, at a right angle from the north, or at some angle from the north which is some simple rational fraction of a right angle. These rhumb lines would be drawn so that they would converge at certain points of the map: lines going in every direction would converge at each of these points. See compass rose. Such maps would necessarily have been in the Mercator projection therefore not all old maps would have been capable of showing rhumb line markings.

The radial lines on a compass rose are also called rhumbs. The expression "sailing on a rhumb" was used in the 16th–19th centuries to indicate a particular compass heading.

Early navigators in the time before the invention of the marine chronometer used rhumb line courses on long ocean passages, because the ship's latitude could be established accurately by sightings of the Sun or stars but there was no accurate way to determine the longitude. The ship would sail north or south until the latitude of the destination was reached, and the ship would then sail east or west along the rhumb line (actually a parallel, which is a special case of the rhumb line), maintaining a constant latitude and recording regular estimates of the distance sailed until evidence of land was sighted.

Generalizations

On the Riemann sphere

Main article: Möbius transformationThe surface of the Earth can be understood mathematically as a Riemann sphere, that is, as a projection of the sphere to the complex plane. In this case, loxodromes can be understood as certain classes of Möbius transformations.

Spheroid

The formulation above can be easily extended to a spheroid. The course of the rhumb line is found merely by using the ellipsoidal isometric latitude. In formulas above on this page, substitute the conformal latitude on the ellipsoid for the latitude on the sphere. Similarly, distances are found by multiplying the ellipsoidal meridian arc length by the secant of the azimuth.

See also

- Great circle

- Geodesics on an ellipsoid

- Great ellipse

- Isoazimuthal

- Rhumbline network

- Seiffert's spiral

- Small circle

References

- ^ Oxford University Press Rhumb Line. The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, Oxford University Press, 2006. Retrieved from Encyclopedia.com 18 July 2009.

- Rhumb at TheFreeDictionary

- ^ Ross, J.M. (editor) (1878). The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information, Vol. IV, Edinburgh-Scotland, Thomas C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works, retrieved from Google Books 2009-03-18;

- Leo Bagrow (2010). History of Cartography. Transaction Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4128-2518-4.

- James Alexander, Loxodromes: A Rhumb Way to Go, "Mathematics Magazine", Vol. 77. No. 5, Dec. 2004.

- A Brief History of British Seapower, David Howarth, pub. Constable & Robinson, London, 2003, chapter 8.

- Smart, W. M. (1946). "On a Problem in Navigation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 106 (2): 124–127. Bibcode:1946MNRAS.106..124S. doi:10.1093/mnras/106.2.124.

- Williams, J. E. D. (1950). "Loxodromic Distances on the Terrestrial Spheroid". Journal of Navigation. 3 (2): 133–140. doi:10.1017/S0373463300045549. S2CID 128651304.

- Carlton-Wippern, K. C. (1992). "On Loxodromic Navigation". Journal of Navigation. 45 (2): 292–297. doi:10.1017/S0373463300010791. S2CID 140735736.

- Bennett, G. G. (1996). "Practical Rhumb Line Calculations on the Spheroid". Journal of Navigation. 49 (1): 112–119. Bibcode:1996JNav...49..112B. doi:10.1017/S0373463300013151. S2CID 128764133.

- Botnev, V.A; Ustinov, S.M. (2014). Методы решения прямой и обратной геодезических задач с высокой точностью [Methods for direct and inverse geodesic problems solving with high precision] (PDF). St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University Journal (in Russian). 3 (198): 49–58.

- Karney, C. F. F. (2024). "The area of rhumb polygons". Studia Geophysica et Geodaetica. 68. doi:10.1007/s11200-024-0709-z.

Note: this article incorporates text from the 1878 edition of The Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information, a work in the public domain

Further reading

- Monmonier, Mark (2004). Rhumb lines and map wars. A social history of the Mercator projection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226534329.

External links

- Constant Headings and Rhumb Lines at MathPages.

- RhumbSolve(1), a utility for ellipsoidal rhumb line calculations (a component of GeographicLib).

- An online version of RhumbSolve.

- Navigational Algorithms Archived 16 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Paper: The Sailings.

- Chart Work - Navigational Algorithms Chart Work free software: Rhumb line, Great Circle, Composite sailing, Meridional parts. Lines of position Piloting - currents and coastal fix.

- Mathworld Loxodrome.

and

and  are the

are the

and

and  is the

is the