Night vision is the ability to see in low-light conditions, either naturally with scotopic vision or through a night-vision device. Night vision requires both sufficient spectral range and sufficient intensity range. Humans have poor night vision compared to many animals such as cats, dogs, foxes and rabbits, in part because the human eye lacks a tapetum lucidum, tissue behind the retina that reflects light back through the retina thus increasing the light available to the photoreceptors.

Types of ranges

Spectral range

Night-useful spectral range techniques can sense radiation that is invisible to a human observer. Human vision is confined to a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum called visible light. Enhanced spectral range allows the viewer to take advantage of non-visible sources of electromagnetic radiation (such as near-infrared or ultraviolet radiation). Some animals such as the mantis shrimp and trout can see using much more of the infrared and/or ultraviolet spectrum than humans.

Intensity range

Sufficient intensity range is simply the ability to see with very small quantities of light.

Many animals have better night vision than humans do, the result of one or more differences in the morphology and anatomy of their eyes. These include having a larger eyeball, a larger lens, a larger optical aperture (the pupils may expand to the physical limit of the eyelids), more rods than cones (or rods exclusively) in the retina, and a tapetum lucidum.

Enhanced intensity range is achieved via technological means through the use of an image intensifier, gain multiplication CCD, or other very low-noise and high-sensitivity arrays of photodetectors.

Biological night vision

Further information: Adaptation (eye) § Accelerating dark adaptation, and Scotopic visionAll photoreceptor cells in the vertebrate eye contain molecules of photoreceptor protein which is a combination of the protein photopsin in color vision cells, rhodopsin in night vision cells, and retinal (a small photoreceptor molecule). Retinal undergoes an irreversible change in shape when it absorbs light; this change causes an alteration in the shape of the protein which surrounds the retinal, and that alteration then induces the physiological process which results in vision.

The retinal must diffuse from the vision cell, out of the eye, and circulate via the blood to the liver where it is regenerated. In bright light conditions, most of the retinal is not in the photoreceptors, but is outside of the eye. It takes about 45 minutes of dark for all of the photoreceptor proteins to be recharged with active retinal, but most of the night vision adaptation occurs within the first five minutes in the dark. Adaptation results in maximum sensitivity to light. In dark conditions only the rod cells have enough sensitivity to respond and to trigger vision.

Rhodopsin in the human rods is insensitive to the longer red wavelengths, so traditionally many people use red light to help preserve night vision. Red light only slowly depletes the rhodopsin stores in the rods, and instead is viewed by the red sensitive cone cells.

Another theory posits that since stars typically emit light with shorter wavelengths, the light from stars will be in the blue-green color spectrum. Therefore, using red light to navigate would not desensitize the receptors used to detect star light.

Many animals have a tissue layer called the tapetum lucidum in the back of the eye that reflects light back through the retina, increasing the amount of light available for it to capture, but reducing the sharpness of the focus of the image. This is found in many nocturnal animals and some deep sea animals, and is the cause of eyeshine. Humans, and monkeys, lack a tapetum lucidum.

Nocturnal mammals have rods with unique properties that make enhanced night vision possible. The nuclear pattern of their rods changes shortly after birth to become inverted. In contrast to conventional rods, inverted rods have heterochromatin in the center of their nuclei and euchromatin and other transcription factors along the border. In addition, the outer layer of cells in the retina (the outer nuclear layer) in nocturnal mammals is thick due to the millions of rods present to process the lower light intensities. The anatomy of this layer in nocturnal mammals is such that the rod nuclei, from individual cells, are physically stacked such that light will pass through eight to ten nuclei before reaching the photoreceptor portion of the cells. Rather than being scattered, the light is passed to each nucleus individually, by a strong lensing effect due to the nuclear inversion, passing out of the stack of nuclei, and into the stack of ten photorecepting outer segments. The net effect of this anatomical change is to multiply the light sensitivity of the retina by a factor of eight to ten with no loss of focus.

Pupillary dilation is a biological process that contributes a relatively minor amount to night vision. In humans, the irises can adjust the size of the pupil from 2 mm in bright light, to as large as 8 mm in dark conditions, but this varies by individual and age, with age causing the maximal pupil diameter to decrease. However, some humans are capable of dilating their pupils to over 9 mm in diameter in the dark, giving them better night vision capabilities.

Night vision technologies

Night vision technologies can be broadly divided into three main categories: image intensification, active illumination, and thermal imaging.

Image intensification

Main article: Image intensifierThis magnifies the amount of received photons from various natural sources such as starlight or moonlight. Examples of such technologies include night glasses and low light cameras. In the military context, Image Intensifiers are often called "Low Light TV" since the video signal is often transmitted to a display within a control center. These are usually integrated into a sensor containing both visible and IR detectors and the streams are used independently or in fused mode, depending on the mission at hand's requirements.

The image intensifier is a vacuum-tube based device (photomultiplier tube) that can generate an image from a very small number of photons (such as the light from stars in the sky) so that a dimly lit scene can be viewed in real-time by the naked eye via visual output, or stored as data for later analysis. While many believe the light is "amplified," it is not. When light strikes a charged photocathode plate, electrons are emitted through a vacuum tube and strike the microchannel plate. This causes the image screen to illuminate with a picture in the same pattern as the light that strikes the photocathode and on a wavelength the human eye can see. This is much like a CRT television, but instead of color guns the photocathode does the emitting.

The image is said to become "intensified" because the output visible light is brighter than the incoming light, and this effect directly relates to the difference in passive and active night vision goggles. Currently, the most popular image intensifier is the drop-in ANVIS module, though many other models and sizes are available at the market. Recently, the US Navy announced intentions to procure a dual-color variant of the ANVIS for use in the cockpit of airborne platforms.

Active illumination

Active illumination couples imaging intensification technology with an active source of illumination in the near infrared (NIR) or shortwave infrared (SWIR) band. Examples of such technologies include low light cameras.

Active infrared night-vision combines infrared illumination of spectral range 700–1,000 nm (just over the visible spectrum of the human eye) with CCD cameras sensitive to this light. The resulting scene, which is apparently dark to a human observer, appears as a monochrome image on a normal display device. Because active infrared night-vision systems can incorporate illuminators that produce high levels of infrared light, the resulting images are typically higher resolution than other night-vision technologies. Active infrared night vision is now commonly found in commercial, residential and government security applications, where it enables effective night time imaging under low-light conditions. However, since active infrared light can be detected by night-vision goggles, there can be a risk of giving away position in tactical military operations.

Laser range gated imaging is another form of active night vision which utilizes a high powered pulsed light source for illumination and imaging. Range gating is a technique which controls the laser pulses in conjunction with the shutter speed of the camera's detectors. Gated imaging technology can be divided into single shot, where the detector captures the image from a single light pulse, and multi-shot, where the detector integrates the light pulses from multiple shots to form an image. One of the key advantages of this technique is the ability to perform target recognition rather than mere detection, as is the case with thermal imaging.

Thermal vision

See also: Thermographic camera and Forward-looking infraredThermal imaging detects the temperature difference between background and foreground objects. Some organisms are able to sense a crude thermal image by means of special organs that function as bolometers. This allows thermal infrared sensing in snakes, which functions by detecting thermal radiation.

Thermal imaging cameras are excellent tools for night vision. They detect thermal radiation and do not need a source of illumination. They produce an image in the darkest of nights and can see through light fog, rain, and smoke (to a certain extent). Thermal imaging cameras make small temperature differences visible. They are widely used to complement new or existing security networks, and for night vision on aircraft, where they are commonly referred to as "FLIR" (for "forward-looking infrared"). When coupled with additional cameras (for example, a visible spectrum camera or SWIR) multispectral sensors are possible, which take advantage of the benefits of each detection band's capabilities. Contrary to misconceptions portrayed in the media, thermal imagers cannot "see" through solid objects (walls, for example), nor can they see through glass or acrylic, as both these materials have their own thermal signature and are opaque to long wave infrared radiation.

Night vision devices

See articles: Night-vision device and Thermal imaging cameraHistory

Before the introduction of image intensifiers, night glasses were the only method of night vision, and thus were widely utilized, especially at sea. Second World War era night glasses usually had a lens diameter of 56 mm or more with magnification of seven or eight. Major drawbacks of night glasses are their large size and weight.

Current technology

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A night vision device (NVD) is a device comprising an image intensifier tube in a rigid casing, commonly used by military forces. Lately, night vision technology has become more widely available for civilian use. For example, enhanced vision systems (EVS) have become available for aircraft, to augment the situational awareness of pilots to prevent accidents. These systems are included in the latest avionics packages from manufacturers such as Cirrus and Cessna. The US Navy has begun procurement of a variant integrated into a helmet-mounted display, produced by Elbit Systems.

A specific type of NVD, the night vision goggle (NVG) is a night vision device with dual eyepieces. The device can utilize either one intensifier tube with the same image sent to both eyes, or a separate image intensifier tube for each eye. Night vision goggles combined with magnification lenses constitutes night vision binoculars. Other types include monocular night vision devices with only one eyepiece which may be mounted to firearms as night sights. NVG and EVS technologies are becoming more popular with helicopter operations, to improve safety. The NTSB is considering EVS as recommended equipment for safety features.

Night glasses are single or binocular with a large diameter objective. Large lenses can gather and concentrate light, thus intensifying light with purely optical means and enabling the user to see better in the dark than with the naked eye alone. Often night glasses also have a fairly large exit pupil of 7 mm or more to let all gathered light into the user's eye. However, many people cannot take advantage of this because of the limited dilation of the human pupil. To overcome this, soldiers were sometimes issued atropine eye drops to dilate pupils.

Currently, the PVS-14 monocular is the most widely used and preferred night vision device across NATO forces. It is used by the United States army, and is known for its low cost and wide range of uses and modification ability. Some higher end devices including the PVS-31 binocular and GPNVG-18 quad-tube night vision are used by special forces groups, but are costly. Monoculars are generally preferred by developed forces.

Night vision systems can also be installed in vehicles. An automotive night vision system is used to improve a vehicle driver's perception and seeing distance in darkness or poor weather. Such systems typically use infrared cameras, sometimes combined with active illumination techniques, to collect information that is then displayed to the driver. Such systems are currently offered as optional equipment on certain premium vehicles.

See also

- Johnson's criteria

- Low light level television

- Night vision device

- Thermal imaging device

- Thermographic camera

- Averted vision

References

- Chijiiwa, Taeko; Ishibashi, Tatsuro; Inomata, Hajime (1990). "Histological study of choroidal melanocytes in animals with tapetum lucidum cellulosum (abstract)". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 228 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1007/BF00935727. PMID 2338254. S2CID 11974069.

- Milius, Susan (2012). "Mantis shrimp flub color vision test". Science News. 182 (6): 11. doi:10.1002/scin.5591820609. JSTOR 23351000.

- "The Human Eye and Single Photons".

- "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and function of the Human Eye" vol. 27, p. 179 Encyclopædia Britannica, 1987

- Bowmaker, J K; Dartnall, H J (1 January 1980). "Visual pigments of rods and cones in a human retina". The Journal of Physiology. 298 (1): 501–511. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013097. PMC 1279132. PMID 7359434.

- Luria, S.M.; Kobus, D.A. (April 1985). "Immediate Visibility after Red and White Adaptation" (PDF). Submarine Base, Groton, CT: Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory (published 26 April 1985). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Luria, S. M.; Kobus, D. A. (July 1984). "THE RELATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF RED AND WHITE LIGHT FOR SUBSEQUENT DARK-ADAPTATION". Submarine Base, Groton, CT: Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory (published 3 July 1984).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Forrest M. Mims III (2013-10-03). "How to Make and Use Retroreflectors". Make. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- J. van de Kraats and D. van Norren: "Directional and nondirectional spectral reflection from the human fovea" J.Biomed. Optics, 13, 024010, 2008

- Solovei, I.; Kreysing, M.; Lanctôt, C.; Kösem, S.; Peichl, L.; Cremer, T.; et al. (April 16, 2009). "Nuclear Architecture of Rod Photoreceptor Cells Adapts to Vision in Mammalian Evolution". Cell. 137 (2): 945–953. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.052. PMID 19379699.

- "Raytheon Multi-Spectral Targeting Systems (MTS)". Archived from the original on 2017-09-03. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "YouTube mp3 indir". mp3video.org.

- "Thermal Infrared vs. Active Infrared: A New Technology Begins to be Commercialized". Archived from the original on January 17, 2010.

- "Extreme CCTV Surveillance Systems". Archived from the original on 2008-04-05. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- J. Bentell; P. Nies; J. Cloots; J. Vermeiren; B. Grietens; O. David; A. Shurkun; R. Schneider. "FLIP CHIPPED InGAaS PHOTODIODE ARRAYS FOR GATED IMAGING WITH EYE-SAFE LASERS" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- Night Vision & Electronic Sensors Directorate - Fort Belvoir, Virginia

- Automotive Night Vision Demonstration

Patents

- US D248860 - Night vision Pocketscope

- US 4707595 - Invisible light beam projector and night vision system

- US 4991183 - Target illuminators and systems employing same

- US 6075644 - Panoramic night vision goggles

- U.S. patent 7,173,237

- US 6158879 - Infra-red reflector and illumination system

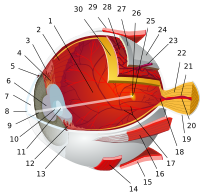

| Anatomy of the globe of the human eye | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrous tunic (outer) |

|  | |||||

| Uvea / vascular tunic (middle) |

| ||||||

| Retina (inner) |

| ||||||

| Anatomical regions of the eye |

| ||||||

| Other | |||||||

| Automotive design | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of a series of articles on cars | |||||||||||||

| Body |

| ||||||||||||

| Exterior equipment |

| ||||||||||||