| Sanjna | |

|---|---|

| Goddess of Clouds | |

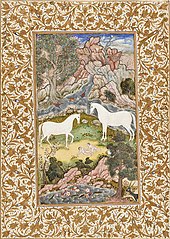

Surya with consorts Samjna and Chhaya, 19th century illustration Surya with consorts Samjna and Chhaya, 19th century illustration | |

| Other names |

|

| Devanagari | संज्ञा |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Saṃjñā |

| Gender | Female |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents |

|

| Siblings | Trisiras (twin brother) Chhaya (reflection) |

| Consort | Surya |

| Children | |

Sanjna (Sanskrit: संज्ञा, IAST: Saṃjñā, also spelled as Samjna and Sangya), also known as Saranyu (Sanskrit: सरण्यू, IAST: Saraṇyū), is a Hindu goddess associated with clouds and the chief consort of Surya, the Sun god. She is mentioned in the Rigveda, the Harivamsa and the Puranas.

In Hindu mythology, Sanjna is the daughter of the craftsman god Tvashtr, often equated with Vishvakarma. Renowned for her beauty, virtue, and ascetic powers, Sanjna married Vivasvant (Surya); however, she could not endure his intense form and energy. To escape, she substituted herself with her shadow or maid, Chhaya, and ran away by transforming into a mare. Upon discovering her absence, Surya had his radiance diminished and brought her back. Sanjna is recognized as the mother of several notable deities, including Yama, the god of death; Yamuna, the river goddess; Vaivasvata Manu, the current patriarch of humans; the twin divine physicians known as the Ashvins; and the god Revanta.

Etymology

Saranyu (or Saraṇyū) is the first name used for the goddess and is derived from the Sanskrit root sar, meaning "to flow" or "to run," which suggests associations with movement, speed, or impetuosity. It is also the female form of the adjective saraṇyú, meaning "quick, fleet, nimble", used for rivers and wind in the Rigveda (compare also Sarayu). This aligns with her mythological role, where she transforms and flees from her circumstances, often depicted as taking the form of a mare. The imagery of flowing or running connects Saranyu to the idea of natural forces, perhaps even hinting at an ancient link with river goddesses. Sometimes, the name is interpreted as "the swift-speeding storm cloud".

In later versions of the myth, particularly in the Harivamsa, the name Samjñā (also written as Sanjna and Sangya) replaces Saraṇyū. Samjñā is derived from the Sanskrit roots sam (together, complete) and jñā (to know), meaning "knowledge," "awareness," "sign," or "name." The shift in name signifies a deeper focus on the character's symbolic role. Samjñā represents more than just a fleeing or transforming figure—she embodies the concept of representation or identity. Indologist Wendy Doniger explains that the change from Saranyu to Samjñā reflects the evolving philosophical concerns in Hindu mythology. While Saranyu is tied to action, motion, and natural forces, Samjñā emphasizes duality—between reality and appearance, self and shadow. The transformation from Saranyu to Samjñā marks a shift from a dynamic, flowing goddess to a figure more concerned with identity and representation. In Samjñā, the myth explores the nature of identity, as the character is literally and metaphorically a sign or image of herself, especially through her surrogate, Chhaya, who is her shadow or reflection.

Doniger also suggests that Samjñā can be understood as a riddle-like term for Sandhya, which represents dawn. In this interpretation, Samjñā’s doppelgänger symbolizes evening twilight, implying that the Sun has two wives: dawn (Sandhya) and twilight (the double). The parallels between Samjñā and Sandhya are striking, as both are portrayed as wives of the Sun with complex, ambivalent relationships. Furthermore, both names carry linguistic significance: while "Samjñā" means "sign" or "image," "Sandhya" is linked to "twilight speech" in later Hindi poetry, which is marked by riddles, inversions, and paradoxes.

According to Skanda Purana, Samjna is also known by the following names—Dyau ('sky'), Rājñī ('queen'), Tvaṣṭrī ('daughter of Tvashtr'), Prabhā ('light') and Lokamātaraḥ (mother of the realm or loka). In some text, Samjna is also referred to by the name Suvarcalā ('resplendent').

In Hindu Literature

Vedas

In the Rig Veda (c. 1200-1000 BCE), Saranyu’s story unfolds as a cryptic narrative, focusing on her marriage to Vivasvant, the Sun god, and the events that follow. Saranyu, the daughter of Tvashtr, gives birth to the twins Yama and Yami after marrying Vivasvant. Soon after, Saranyu mysteriously disappears, leaving behind a substitute—a savarna, or a female of the same kind. The text hints that this substitute, created to take her place, is given to Vivasvant, while Saranyu, in her own form, flees, taking on the guise of a mare. The Rig Veda narrates that after Saranyu assumes the form of a mare and departs, Vivasvant takes on the form of a stallion and follows her. In their union as horses, Saranyu gives birth to the twin equine gods, the Ashvins. These gods, half horse and half human, are later described as liminal figures—connected to both the divine and the mortal realms. After giving birth to the Ashvins, Saranyu abandons both her mortal children, Yama and Yami, as well as the newly born Ashvins. The story in the Rig Veda presents these events in a fragmented and riddle-like manner, with no explicit explanations for Saranyu's actions or the creation of her double.

In the Nirukta (c. 500 BCE) by the linguist Yaska, the story is expanded with additional details. Saranyu’s actions are clarified, and she is said to have taken on the form of a mare of her own volition. Vivasvant, upon discovering her transformation, follows her in the form of a horse and mates with her, leading to the birth of the Ashvins. The text also introduces the birth of Manu, who is born from the savarna, Saranyu’s substitute. Manu becomes the progenitor of the human race, marking the transition from divine to mortal beings in Saranyu’s offspring.

The Brhaddevata (composed few centuries after Nirukta) further elaborates on the story. Here, Saranyu is described as having a twin brother with three heads (Trishiras). She willingly leaves Vivasvant by creating a female who looks like her and entrusting her children to this substitute. While Vivasvant unknowingly has Manu with the savarna, he later realizes that Saranyu has left and goes after her in the form of a horse. Their union as horses produces the Ashvins, who are conceived in an unconventional manner—Saranyu inhales the semen that had fallen on the ground, leading to the twins' birth.

Wendy Doniger and other scholars have suggested that the cryptic nature of the Rig Veda's narrative about Saranyu is not accidental but a deliberate feature of Vedic literature. Doniger, in particular, emphasizes that the story of Saranyu is shrouded in what the Vedas term brahmodya, or "mystical utterances." These are enigmatic verses that present mythological events in riddle-like form, leaving the audience to decipher the underlying meanings and connections. This approach reflects the Vedic method of storytelling, where stories were often concealed and revealed in parts, requiring interpretation by the reader or listener. Maurice Bloomfield, as cited by Doniger, further explains that the passage about Saranyu belongs to a category of Vedic riddles or charades. The deliberate withholding of explanations about key events—such as Saranyu’s disappearance, the creation of her double, and the birth of the Ashvins—suggests that these verses are meant to provoke thought rather than provide straightforward answers. According to Bloomfield, the text invites its audience to solve the riddle by connecting the clues offered, with Saranyu’s name being the final piece of the puzzle.

One of the central themes scholars explore is the nature of Saranyu’s flight and the creation of her double. Doniger highlights that Saranyu, whose name means "flowing" (possibly hinting at a river or a swift-moving force), leaves behind a mortal double, the savarna. This act introduces a key tension between divine and mortal realms, particularly through the creation of the savarna, a mortal replacement for an immortal goddess. The double is described as "of the same kind"—either in appearance or nature—but crucially different in her mortal status, which allows Vivasvant, a god with mortal aspects, to father Manu with her. This duality of Saranyu and her double is a major focus of later interpretations, as it touches on the complex intersection of divine and human procreation. Doniger also discusses the gender and power dynamics implicit in the story. In early Vedic literature, divine figures like Saranyu often operate in ways that question agency—was her flight an act of autonomy, or was it imposed upon her by the gods or by circumstances? This question becomes central to later retellings of the myth. For example, in the Nirukta, Saranyu is said to have created the double herself and fled in her own volition. This narrative suggests that she was an active agent in her own escape and in the creation of the savarna, which complicates the traditional portrayal of women in Vedic literature as passive or controlled by male figures. Additionally, the shift in the nature of Saranyu's union with Vivasvant—from a divine, celestial marriage to a peculiar equine coupling—raises questions about the boundaries between human and divine sexuality. Doniger interprets this transformation as symbolic of the fluidity between forms and identities in Vedic myth. By fleeing as a mare and being pursued as a stallion, Saranyu and Vivasvant transcend the normal boundaries of human and divine relationships, leading to the birth of the liminal Ashvins, who exist between mortal and immortal worlds. This also reflects the broader Vedic theme that divine procreation is not bound by human conventions.

Another aspect scholars focus on is the concept of twinhood. Yama and Yami are born to Saranyu as mortal twins, while the Ashvins are born to her as divine twins in the form of horses. Doniger points out that the concept of twinhood extends beyond simple sibling relationships in Vedic mythology; it symbolizes duality, opposites, and complementary forces, with Yama representing death and the Ashvins embodying healing and life. This duality is reinforced by Saranyu’s dual identity as both the mother of Yama, the first mortal, and the divine Ashvins. Saranyu's role as the mother of both human and divine progeny also marks a significant moment in Vedic mythology. Before her, goddesses like Aditi give birth to immortal children, but Saranyu, through her double, introduces the birth of mortal beings, namely Manu, the ancestor of humanity. This blending of divine and mortal realms in her offspring reflects a broader Vedic concern with the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, as seen in the daily rise and fall of the sun—an event often associated with Vivasvant in later interpretations.

Harivamsa

In the Harivamsa, the appendix to the epic Mahabharata, the myth of Saranyu undergoes significant transformations from its earlier Vedic representations. In this later narrative, Saranyu is renamed Samjna, while the surrogate she creates is no longer described as merely of-the-same-kind (savarna) but is instead depicted as her chhaya—her shadow or mirror image. This change introduces a dynamic of inversion, where the shadow not only resembles Samjna but also contrasts with her in key ways.

Samjna is portrayed as the daughter of Tvashtr, and she is married to Vivasvant, the Sun. Although she is virtuous, beautiful and has great ascetic powers, she becomes increasingly dissatisfied with her husband. Vivasvant’s radiant heat is excessive, rendering his form unappealing to Samjna. He is referred to as Martanda or "Dead-Egg." His intense radiance has disfigured his limbs and darkened his complexion (syama varna). Samjna, unable to bear the Sun’s overwhelming heat and appearance, devises a plan to escape. She creates a magical double of herself—a shadow or chhaya—that resembles her but behaves differently. Samjna instructs this shadow to take her place and care for her three children: Manu, Yama, and Yamuna. She warns the shadow not to reveal the truth to Vivasvant, and then she flees to her father Tvashtr’s house. At her father Tvashtr’s house, Samjna seeks refuge but is met with harsh disapproval. Tvashtr tells her she must fulfill her marital duties and return to her husband. To avoid returning, she transforms herself into a mare and flees to the land of the northern Kurus, where she hides and grazes in an uninhabited region.

Meanwhile, Vivasvant remains unaware of the substitution and continues his life with the shadow Samjna, believing her to be his true wife. Together, they have a son named Manu Savarni, meaning "of-the-same-kind" as the first Manu. The shadow Samjna, however, does not treat Samjna’s earlier children—Manu, Yama, and Yamuna—with equal affection. She favors her own son, Manu Savarni, while neglecting the others. This favoritism leads to conflict, especially with Yama, who becomes resentful. In a moment of anger, Yama raises his foot to strike the shadow mother, but refrains from doing so. Enraged by his action, the shadow curses Yama, declaring that his foot will fall off. Yama, distressed by the curse, turns to Vivasvant for help. Vivasvant, sympathetic to his son's plight, cannot entirely revoke the curse but mitigates its effects by declaring that worms will consume part of Yama’s foot, sparing him from complete loss. Suspicious of the shadow’s behavior, Vivasvant confronts her and demands an explanation for her favoritism. Under pressure, the shadow reveals the truth: she is not the real Samjna but merely a shadow double. Infuriated, Vivasvant seeks out Tvashtr for assistance. Tvashtr, in turn, tempers the Sun's fiery nature, reducing his excessive heat and making his form more pleasant. Vivasvant then sets out to find the real Samjna, locating her in the form of a mare in the northern Kurus. To approach her, he takes on the form of a stallion and unite in their equine forms. However, fearing it might be another male, Samjna expels the Sun’s seed through her nostrils, giving birth to the twin gods—Ashvins. After this encounter, Vivasvant reveals his transformed, more appealing form to Samjna. Satisfied by his new appearance, Samjna reconciles with him, and they return to their life together.

Wendy Doniger highlights several key differences between the Harivamsa version of the Saranyu myth and its earlier Vedic counterparts. In this later text, the concept of the shadow (chhaya) takes on a more prominent role, symbolizing both resemblance and opposition. Doniger points out that the use of varna—meaning "color" or "class"—introduces themes of difference between Samjna and the Sun, particularly regarding his dark complexion, which is a cause of her dissatisfaction. This interpretation also ties into broader social meanings of varna in ancient texts, where it began to reflect both racial and class distinctions. Doniger further suggests that the depiction of the Sun as dark or black in the Harivamsa may have roots in Indo-European mythologies, which occasionally describe the sun as black due to its underworld journey or as a result of direct observation of its overwhelming radiance.

Puranas

Samjna's narrative is retold in multiple Puranas. Among them, the Markandeya Purana contains the most elaborate account. According to Wendy Doniger, this retelling serves an important function in Puranic literature, linking older Vedic deities with newer Puranic concepts, especially in relation to the rise of goddess worship. Specifically, the Markandeya Purana uses the Samjna story to introduce the Devi Mahatmya, a text central to the worship of the Goddess (Devi), signaling the assimilation of female divinities from non-Sanskrit vernacular traditions into the classical Sanskrit canon.

The myth of Samjna is narrated twice in the Markandeya Purana. Samjna, the daughter of Tvastr, marries Vivasvant, from whom she bears Manu, who is extremely beloved to Vivasvant. In contrast to earlier versions, the Markandeya Purana does not emphasize the Sun’s physical appearance, as noted in the Harivamsa. Instead, the narrative focuses on Samjna’s inability to tolerate the Sun's overwhelming splendor and fiery energy, referred to as tejas. Unable to endure this intensity, Samjna closes her eyes whenever she sees him. Vivasvant, angered by this reaction, curses her, declaring that she will give birth to a son, Yama, who will be the embodiment of restraint (samyama), a reflection of her own restrained vision. As her gaze flickers and darts about in fear, Samjna is further cursed to give birth to a daughter, Yamuna, who will become a river that flows in a similarly erratic manner. Unable to further tolerate her husband’s fiery energy, Samjna leaves behind her own personified shadow, named Chhaya, and goes to her father's house. Initially, Tvashtr welcomes Samjna; however, after she stays there for many years, he soon forces her to leave his home and return to her husband. Samjna then transforms into a mare and hides in the land of the northern Kurus. The story proceeds as Chhaya raises Samjna’s children, Manu, Yama, and Yamuna, but shows favoritism towards her own offsprings—Savarni Manu, Shani and Tapati. Yama, noticing this difference in treatment, confronts Chhaya, who in anger curses him. The curse, similar to the one in the Harivamsa, focuses on Yama’s foot: “Since you threaten your father’s wife with your foot, your foot will fall.” Yama suspects that Chhaya is not his real mother, as he notes that a true mother would not curse her child even in anger. Vivasvant eventually realizes that Chhaya is an imposter and seeks out the real Samjna, who is hiding in her mare form. Vivasvant, after having some of his fiery tejas reduced by the gods, transforms himself into a stallion and approaches Samjna in her mare form. The myth recounts their unusual reunion, resulting in the conception of the Ashvins. The Markandeya Purana also introduces a new character, Revanta, born from the Sun’s remaining seed after the Ashvins’ conception. Revanta becomes an important figure, riding a horse, symbolizing both Samjna’s equine transformation and the divine progeny she bears. After the birth of their children, Vivasvant reveals his true form to Samjna, now cleansed of his excessive energy. Satisfied with this transformation, she returns to her original form and reclaims her rightful place as his wife.

In the Vishnu Purana, a similar legend is recited by sage Parashara, but here instead of Tvashtr, Samjna is identified as the daughter of Vishvakarman, the divine architect and craftsman. Additionally, Samjna’s departure is more explicitly linked to her desire to perform tapas (penance) in the forest to gain control over the Sun's heat. The Vishnu Purana, in contrast to other texts, also states that the Sun’s heat is reduced after he finds and brings Samjna back. This reduction is prompted by her complaints to her father, Vishvakarman, regarding the unbearable heat of her husband. Vishvakarma reduces 1/8th of Surya's radiance and using it, he creates many celestial weapons including Vishnu's disc, Shiva's trident and Kartikeya's vel.

Most Puranic scriptures mention 6 children of Surya by Samjna—Vaivasvata Manu, Yama, Yamuna, Ashvins and Revanta. However, Kurma Purana and Bhagavata Purana gives Samjna only three children — Manu, Yama and Yamuna. Markandeya Purana as well as Vishnudharmottara Purana prescribe that Surya should be depicted in images with Samjna and his other wives by his sides. The Skanda Purana identifies Samjna’s mother as Rechana or Virochanā, the daughter of the pious daitya Prahlada and the wife of Tvashtr. Additionally, it equates Samjna with Rajni and Prabha, who are mentioned as distinct wives of Surya in a few different texts, particularly those related to his iconography.

Notes

- In the Kurma Purana, Rajni and Prabha are the names of other wives of Surya, distinct from Samjna.

References

- Kinsley, David R (1986). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. University of California Press. ISBN 81-208-0379-5.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (1998). "Saranyu/Samjna". In John Stratton Hawley, Donna Marie Wulff (ed.). Devī: goddesses of India. Motilal Banarsidas. pp. 154–7. ISBN 81-208-1491-6.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Erinyes" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 745.

- ^ Doniger, Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions Wendy; Doniger, Wendy; O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger (June 1999). Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15640-8.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (December 1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ Dr. G.V. Tagare (1995). "|access-date=2024-09-28 Chapter 11". The Skanda-Purana. Internet Archive. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapter= - ^ Rao, T. A. Gopinatha (1914). Elements Of Hindu Iconography Vol. 1, Part. 2.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (September 2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. ISBN 978-0-89281-807-5.

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kumar (1997), "Revanta in Puranic Literature and Art", Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, vol. 44, Anmol Publications, pp. 2605–19, ISBN 81-7488-168-9

- ^ Puranic Encyclopedia: a comprehensive dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature, Vettam Mani, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1975, p. Samjñā

- Wilson, Horace Hayman (1866). "II". The Vishńu Puráńa: a system of Hindu mythology and tradition. Vol. 8. London: Trubner & Co. pp. 20–23.

- Prabhupada. "Bhaktivedanta VedaBase: Śrīmad Bhāgavatam: Chapter 13: Description of Future Manus". The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Shashi, S. S. (1997). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Vol. 100. Anmol Publications. pp. 877, 917. ISBN 9788170418597.

External links

Media related to Samjna at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samjna at Wikimedia Commons

| Hindu deities and texts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gods |  | |

| Goddesses | ||

| Other deities | ||

| Texts (list) | ||