A scene graph is a general data structure commonly used by vector-based graphics editing applications and modern computer games, which arranges the logical and often spatial representation of a graphical scene. It is a collection of nodes in a graph or tree structure. A tree node may have many children but only a single parent, with the effect of a parent applied to all its child nodes; an operation performed on a group automatically propagates its effect to all of its members. In many programs, associating a geometrical transformation matrix (see also transformation and matrix) at each group level and concatenating such matrices together is an efficient and natural way to process such operations. A common feature, for instance, is the ability to group related shapes and objects into a compound object that can then be manipulated as easily as a single object.

Scene graphs in graphics editing tools

In vector-based graphics editing, each leaf node in a scene graph represents some atomic unit of the document, usually a shape such as an ellipse or Bezier path. Although shapes themselves (particularly paths) can be decomposed further into nodes such as spline nodes, it is practical to think of the scene graph as composed of shapes rather than going to a lower level of representation.

Another useful and user-driven node concept is the layer. A layer acts like a transparent sheet upon which any number of shapes and shape groups can be placed. The document then becomes a set of layers, any of which can be conveniently made invisible, dimmed, or locked (made read-only). Some applications place all layers in a linear list, while others support layers within layers to any desired depth.

Internally, there may be no real structural difference between layers and groups at all, since they are both just nodes of a scene graph. If differences are needed, a common type declaration in C++ would be to make a generic node class, and then derive layers and groups as subclasses. A visibility member, for example, would be a feature of a layer, but not necessarily of a group.

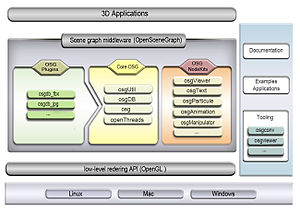

Scene graphs in games and 3D applications

Scene graphs are useful for modern games using 3D graphics and increasingly large worlds or levels. In such applications, nodes in a scene graph (generally) represent entities or objects in the scene.

For instance, a game might define a logical relationship between a knight and a horse so that the knight is considered an extension to the horse. The scene graph would have a 'horse' node with a 'knight' node attached to it.

The scene graph may also describe the spatial, as well as the logical, relationship of the various entities: the knight moves through 3D space as the horse moves.

In these large applications, memory requirements are major considerations when designing a scene graph. For this reason, many large scene graph systems use geometry instancing to reduce memory costs and increase speed. In our example above, each knight is a separate scene node, but the graphical representation of the knight (made up of a 3D mesh, textures, materials and shaders) is instanced. This means that only a single copy of the data is kept, which is then referenced by any 'knight' nodes in the scene graph. This allows a reduced memory budget and increased speed, since when a new knight node is created, the appearance data needs not be duplicated.

Scene graph implementation

The simplest form of scene graph uses an array or linked list data structure, and displaying its shapes is simply a matter of linearly iterating the nodes one by one. Other common operations, such as checking to see which shape intersects the mouse pointer are also done via linear searches. For small scene graphs, this tends to suffice.

Scene graph operations and dispatch

Applying an operation on a scene graph requires some way of dispatching an operation based on a node's type. For example, in a render operation, a transformation group node would accumulate its transformation by matrix multiplication, vector displacement, quaternions or Euler angles. After which a leaf node sends the object off for rendering to the renderer. Some implementations might render the object directly, which invokes the underlying rendering API, such as DirectX or OpenGL. But since the underlying implementation of the rendering API usually lacks portability, one might separate the scene graph and rendering systems instead. In order to accomplish this type of dispatching, several different approaches can be taken.

In object-oriented languages such as C++, this can easily be achieved by virtual functions, where each represents an operation that can be performed on a node. Virtual functions are simple to write, but it is usually impossible to add new operations to nodes without access to the source code. Alternatively, the visitor pattern can be used. This has a similar disadvantage in that it is similarly difficult to add new node types.

Other techniques involve the use of RTTI (Run-Time Type Information). The operation can be realised as a class that is passed to the current node; it then queries the node's type using RTTI and looks up the correct operation in an array of callbacks or functors. This requires that the map of types to callbacks or functors be initialized at runtime, but offers more flexibility, speed and extensibility.

Variations on these techniques exist, and new methods can offer added benefits. One alternative is scene graph rebuilding, where the scene graph is rebuilt for each of the operations performed. This, however, can be very slow, but produces a highly optimised scene graph. It demonstrates that a good scene graph implementation depends heavily on the application in which it is used.

Traversals

Traversals are the key to the power of applying operations to scene graphs. A traversal generally consists of starting at some arbitrary node (often the root of the scene graph), applying the operation(s) (often the updating and rendering operations are applied one after the other), and recursively moving down the scene graph (tree) to the child nodes, until a leaf node is reached. At this point, many scene graph engines then traverse back up the tree, applying a similar operation. For example, consider a render operation that takes transformations into account: while recursively traversing down the scene graph hierarchy, a pre-render operation is called. If the node is a transformation node, it adds its own transformation to the current transformation matrix. Once the operation finishes traversing all the children of a node, it calls the node's post-render operation so that the transformation node can undo the transformation. This approach drastically reduces the necessary amount of matrix multiplication.

Some scene graph operations are actually more efficient when nodes are traversed in a different order – this is where some systems implement scene graph rebuilding to reorder the scene graph into an easier-to-parse format or tree.

For example, in 2D cases, scene graphs typically render themselves by starting at the tree's root node and then recursively draw the child nodes. The tree's leaves represent the most foreground objects. Since drawing proceeds from back to front with closer objects simply overwriting farther ones, the process is known as employing the Painter's algorithm. In 3D systems, which often employ depth buffers, it is more efficient to draw the closest objects first, since farther objects often need only be depth-tested instead of actually rendered, because they are occluded by nearer objects.

Scene graphs and bounding volume hierarchies (BVHs)

Bounding Volume Hierarchies (BVHs) are useful for numerous tasks – including efficient culling and speeding up collision detection between objects. A BVH is a spatial structure, but doesn't have to partition the geometry (see spatial partitioning below).

A BVH is a tree of bounding volumes (often spheres, axis-aligned bounding boxes or oriented bounding boxes). At the bottom of the hierarchy, the size of the volume is just large enough to encompass a single object tightly (or possibly even some smaller fraction of an object in high resolution BVHs). As one ascends the hierarchy, each node has its own volume that tightly encompasses all the volumes beneath it. At the root of the tree is a volume that encompasses all the volumes in the tree (the whole scene).

BVHs are useful for speeding up collision detection between objects. If an object's bounding volume does not intersect a volume higher in the tree, it cannot intersect any object below that node (so they are all rejected very quickly).

There are some similarities between BVHs and scene graphs. A scene graph can easily be adapted to include/become a BVH – if each node has a volume associated or there is a purpose-built "bound node" added in at convenient location in the hierarchy. This may not be the typical view of a scene graph, but there are benefits to including a BVH in a scene graph.

Scene graphs and spatial partitioning

An effective way of combining spatial partitioning and scene graphs is by creating a scene leaf node that contains the spatial partitioning data. This can increase computational efficiency of rendering.

Spatial data is usually static and generally contains non-moving scene data in some partitioned form. Some systems may have the systems and their rendering separately. This is fine and there are no real advantages to either method. In particular, it is bad to have the scene graph contained within the spatial partitioning system, as the scene graph is better thought of as the grander system to the spatial partitioning.

Very large drawings, or scene graphs that are generated solely at runtime (as happens in ray tracing rendering programs), require defining of group nodes in a more automated fashion. A raytracer, for example, will take a scene description of a 3D model and build an internal representation that breaks up its individual parts into bounding boxes (also called bounding slabs). These boxes are grouped hierarchically so that ray intersection tests (as part of visibility determination) can be efficiently computed. A group box that does not intersect an eye ray, for example, can entirely skip testing any of its members.

A similar efficiency holds in 2D applications as well. If the user has magnified a document so that only part of it is visible on his computer screen, and then scrolls in it, it is useful to use a bounding box (or in this case, a bounding rectangle scheme) to quickly determine which scene graph elements are visible and thus actually need to be drawn.

Depending on the particulars of the application's drawing performance, a large part of the scene graph's design can be impacted by rendering efficiency considerations. In 3D video games such as Quake, binary space partitioning (BSP) trees are heavily favored to minimize visibility tests. BSP trees, however, take a very long time to compute from design scene graphs, and must be recomputed if the design scene graph changes, so the levels tend to remain static, and dynamic characters aren't generally considered in the spatial partitioning scheme.

Scene graphs for dense regular objects such as heightfields and polygon meshes tend to employ quadtrees and octrees, which are specialized variants of a 3D bounding box hierarchy. Since a heightfield occupies a box volume itself, recursively subdividing this box into eight subboxes (hence the 'oct' in octree) until individual heightfield elements are reached is efficient and natural. A quadtree is simply a 2D octree.

Standards

PHIGS

PHIGS was the first commercial scene graph specification, and became an ANSI standard in 1988. Disparate implementations were provided by Unix hardware vendors. The HOOPS 3D Graphics System appears to have been the first commercial scene graph library provided by a single software vendor. It was designed to run on disparate lower-level 2D and 3D interfaces, with the first major production version (v3.0) completed in 1991.

SGI

Silicon Graphics (SGI) released OpenGL Performer or more commonly called Performer in 1991 which was the primary scenegraph system for most SGI products into the future. IRIS Inventor 1.0 (1992) was released by SGI, which was a high level scene graph built on top of Performer. It was followed up with Open Inventor in 1994, another iteration of the high level scene graph built on top of newer releases of Performer. More 3D scene graph libraries can be found in Category:3D scenegraph APIs.

X3D

X3D is a royalty-free open standards file format and run-time architecture to represent and communicate 3D scenes and objects using XML. It is an ISO-ratified standard that provides a system for the storage, retrieval and playback of real-time graphics content embedded in applications, all within an open architecture to support a wide array of domains and user scenarios.

See also

References

| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Books

- Leler, Wm and Merry, Jim (1996) 3D with HOOPS, Addison-Wesley

- Wernecke, Josie (1994) The Inventor Mentor: Programming Object-Oriented 3D Graphics with Open Inventor, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-62495-8 (Release 2)

Articles

- Bar-Zeev, Avi. "Scenegraphs: Past, Present, and Future"

- Carey, Rikk and Bell, Gavin (1997). "The Annotated VRML 97 Reference Manual"

- James H. Clark (1976). "Hierarchical Geometric Models for Visible Surface Algorithms". Communications of the ACM. 19 (10): 547–554. doi:10.1145/360349.360354.

- Helman, Jim; Rohlf, John (1994). "IRIS Performer: A High Performance Multiprocessing Toolkit for Real-Time 3D Graphics"

- PEXTimes – "Unofficially, the PHIGS Extension to X. Officially, PEX was not an acronym."

- Strauss, Paul (1993). "IRIS Inventor, a 3D Graphics Toolkit"