| Sea otter | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Morro Bay, California | |

| Conservation status | |

Endangered (IUCN 3.1) | |

| CITES Appendix II (CITES) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Subfamily: | Lutrinae |

| Genus: | Enhydra |

| Species: | E. lutris |

| Binomial name | |

| Enhydra lutris (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Sea otter range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The sea otter (Enhydra lutris) is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between 14 and 45 kg (30 and 100 lb), making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the smallest marine mammals. Unlike most marine mammals, the sea otter's primary form of insulation is an exceptionally thick coat of fur, the densest in the animal kingdom. Although it can walk on land, the sea otter is capable of living exclusively in the ocean.

The sea otter inhabits nearshore environments, where it dives to the sea floor to forage. It preys mostly on marine invertebrates such as sea urchins, various mollusks and crustaceans, and some species of fish. Its foraging and eating habits are noteworthy in several respects. Its use of rocks to dislodge prey and to open shells makes it one of the few mammal species to use tools. In most of its range, it is a keystone species, controlling sea urchin populations which would otherwise inflict extensive damage to kelp forest ecosystems. Its diet includes prey species that are also valued by humans as food, leading to conflicts between sea otters and fisheries.

Sea otters, whose numbers were once estimated at 150,000–300,000, were hunted extensively for their fur between 1741 and 1911, and the world population fell to 1,000–2,000 individuals living in a fraction of their historic range. A subsequent international ban on hunting, sea otter conservation efforts, and reintroduction programs into previously populated areas have contributed to numbers rebounding, and the species occupies about two-thirds of its former range. The recovery of the sea otter is considered an important success in marine conservation, although populations in the Aleutian Islands and California have recently declined or have plateaued at depressed levels. For these reasons, the sea otter remains classified as an endangered species.

Evolution

The sea otter is the heaviest (the giant otter is longer, but significantly slimmer) member of the family Mustelidae, a diverse group that includes the 13 otter species and terrestrial animals such as weasels, badgers, and minks. It is unique among the mustelids in not making dens or burrows, in having no functional anal scent glands, and in being able to live its entire life without leaving the water. The only living member of the genus Enhydra, the sea otter is so different from other mustelid species that, as recently as 1982, some scientists believed it was more closely related to the earless seals. Genetic analysis indicates the sea otter and its closest extant relatives, which include the African speckle-throated otter, Eurasian otter, African clawless otter and Asian small-clawed otter, shared an ancestor approximately 5 million years ago.

Fossil evidence indicates the Enhydra lineage became isolated in the North Pacific approximately 2 million years ago, giving rise to the now-extinct Enhydra macrodonta and the modern sea otter, Enhydra lutris. One related species has been described, Enhydra reevei, from the Pleistocene of East Anglia. The modern sea otter evolved initially in northern Hokkaidō and Russia, and then spread east to the Aleutian Islands, mainland Alaska, and down the North American coast. In comparison to cetaceans, sirenians, and pinnipeds, which entered the water approximately 50, 40, and 20 million years ago, respectively, the sea otter is a relative newcomer to a marine existence. In some respects, though, the sea otter is more fully adapted to water than pinnipeds, which must haul out on land or ice to give birth. The full genome of the northern sea otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) was sequenced in 2017 and may allow for examination of the sea otter's evolutionary divergence from terrestrial mustelids. Following their divergence from their most common ancestor five million years ago, sea otters have developed traits dependent on polygenic selection, or the evolution of numerous traits to create hallmark features like thick and oily fur and large bones, compared to their freshwater sister species. Sea otters require these traits to survive the cold waters of the northern Pacific Ocean, in which they spend their entire lives despite occasionally coming out of the water as pups. Sea otters have the thickest fur of any animal (~1,000,000 hairs per square inch), as they do not have a blubber layer, while their oil glands help matt down their fur and keep it from holding air. Thick bones also prove crucial in increasing buoyancy, as sea otters spend long hours floating atop the ocean. In a study, southern and northern Sea Otter populations were compared against the African clawless otter, and it was determined that aquatic traits like loss of smell and hair thickness independently evolved, evidencing a complex genome of polygenic traits resulting in complex systems. This study was only able to take place after sequencing of Sea Otter nuclear genomes and through phylogeny to find a close ancestor with which to compare genomes.

Previously, it was suspected that sea otters came from the same evolutionary branch as earless seals, such as harbor and monk seals. Sea Otters have experienced numerous population bottlenecks throughout their history, with significant numbers being wiped out 9,000-10,000 generations ago and 300–700 generations ago, long before the fur trade. These previous genetic bottlenecks are responsible for already low genetic diversity amongst species members, making the secondary bottleneck caused by the fur trade more significant. These primary bottlenecks were most likely caused by disease, a common cause for genetic bottlenecks. Estimates place these bottlenecks at leaving around ten to forty animals for about eight to forty-four years. This led to genetic drift, as the populations of northern and southern sea otters were cut off from one another by thousands of miles, leading to significant genomic differences. However, the modern population bottleneck caused by the fur trade of the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries presents the most significant concern to scientists and conservationists attempting to recover population numbers and genetic diversity. Each bottleneck has lowered genomic diversity and thus increased the chance of deleterious genetic drift.

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram showing relationships between sea otters and other otters |

The first scientific description of the sea otter is contained in the field notes of Georg Steller from 1751, and the species was described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. Originally named Lutra marina, it underwent numerous name changes before being accepted as Enhydra lutris in 1922. The generic name Enhydra, derives from the Ancient Greek en/εν "in" and hydra/ύδρα "water", meaning "in the water", and the Latin word lutris, meaning "otter". It was formerly sometimes referred to as the "sea beaver".

Subspecies

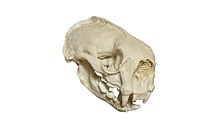

Three subspecies of the sea otter are recognized with distinct geographical distributions. Enhydra lutris lutris (nominate), the Asian sea otter, ranges across Russia's Kuril Islands northeast of Japan, and the Commander Islands in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. In the eastern Pacific Ocean, E. l. kenyoni, the northern sea otter, is found from Alaska's Aleutian Islands to Oregon and E. l. nereis, the southern sea otter, is native to central and southern California. The Asian sea otter is the largest subspecies and has a slightly wider skull and shorter nasal bones than both other subspecies. Northern sea otters possess longer mandibles (lower jaws) while southern sea otters have longer rostrums and smaller teeth.

Description

The sea otter is one of the smallest marine mammal species, but it is the heaviest mustelid. Male sea otters usually weigh 22 to 45 kg (49 to 99 lb) and are 1.2 to 1.5 m (3 ft 11 in to 4 ft 11 in) in length, though specimens up to 54 kg (119 lb) have been recorded. Females are smaller, weighing 14 to 33 kg (31 to 73 lb) and measuring 1.0 to 1.4 m (3 ft 3 in to 4 ft 7 in) in length. The average weight for adult sea otters that are in more densely populated areas, at 28.3 kg (62 lb) in males and 21.1 kg (47 lb) in females, was considerably lighter than the average weight of otters in more sparse populations, at 39.3 kg (87 lb) in males and 25.2 kg (56 lb) in females Presumably less populous otters are more able to monopolize food sources, For its size, the male otter's baculum is very large, massive and bent upwards, measuring 150 mm (5+7⁄8 in) in length and 15 mm (9⁄16 in) at the base.

Unlike most other marine mammals, the sea otter has no blubber and relies on its exceptionally thick fur to keep warm. With up to 150,000 strands of hair per square centimetre (970,000/in), its fur is the densest of any animal. The fur consists of long, waterproof guard hairs and short underfur; the guard hairs keep the dense underfur layer dry. There is an air compartment between the thick fur and the skin where air is trapped and heated by the body. Cold water is kept completely away from the skin and heat loss is limited. However, a potential disadvantage of this form of insulation is compression of the air layer as the otter dives, thereby reducing the insulating quality of fur at depth when the animal forages. The fur is thick year-round, as it is shed and replaced gradually rather than in a distinct molting season. As the ability of the guard hairs to repel water depends on utmost cleanliness, the sea otter has the ability to reach and groom the fur on any part of its body, taking advantage of its loose skin and an unusually supple skeleton. The coloration of the pelage is usually deep brown with silver-gray speckles, but it can range from yellowish or grayish brown to almost black. In adults, the head, throat, and chest are lighter in color than the rest of the body.

The sea otter displays numerous adaptations to its marine environment. The nostrils and small ears can close. The hind feet, which provide most of its propulsion in swimming, are long, broadly flattened, and fully webbed. The fifth digit on each hind foot is longest, facilitating swimming while on its back, but making walking difficult. The tail is fairly short, thick, slightly flattened, and muscular. The front paws are short with retractable claws, with tough pads on the palms that enable gripping slippery prey. The bones show osteosclerosis, increasing their density to reduce buoyancy.

The sea otter presents an insight into the evolutionary process of the mammalian invasion of the aquatic environment, which has occurred numerous times over the course of mammalian evolution. Having only returned to the sea about 3 million years ago, sea otters represent a snapshot at the earliest point of the transition from fur to blubber. In sea otters, fur is still advantageous, given their small nature and division of lifetime between the aquatic and terrestrial environments. However, as sea otters evolve and adapt to spending more and more of their lifetimes in the sea, the convergent evolution of blubber suggests that the reliance on fur for insulation would be replaced by a dependency on blubber. This is particularly true due to the diving nature of the sea otter; as dives become lengthier and deeper, the air layer's ability to retain heat or buoyancy decreases, while blubber remains efficient at both of those functions. Blubber can also additionally serve as an energy source for deep dives, which would most likely prove advantageous over fur in the evolutionary future of sea otters.

The sea otter propels itself underwater by moving the rear end of its body, including its tail and hind feet, up and down, and is capable of speeds of up to 9 kilometres per hour (5.6 mph). When underwater, its body is long and streamlined, with the short forelimbs pressed closely against the chest. When at the surface, it usually floats on its back and moves by sculling its feet and tail from side to side. At rest, all four limbs can be folded onto the torso to conserve heat, whereas on particularly hot days, the hind feet may be held underwater for cooling. The sea otter's body is highly buoyant because of its large lung capacity – about 2.5 times greater than that of similar-sized land mammals – and the air trapped in its fur. The sea otter walks with a clumsy, rolling gait on land, and can run in a bounding motion.

Long, highly sensitive whiskers and front paws help the sea otter find prey by touch when waters are dark or murky. Researchers have noted when they approach in plain view, sea otters react more rapidly when the wind is blowing towards the animals, indicating the sense of smell is more important than sight as a warning sense. Other observations indicate the sea otter's sense of sight is useful above and below the water, although not as good as that of seals. Its hearing is neither particularly acute nor poor.

An adult's 32 teeth, particularly the molars, are flattened and rounded for crushing rather than cutting food. Seals and sea otters are the only carnivores with two pairs of lower incisor teeth rather than three; the adult dental formula is 3.1.3.12.1.3.2. The teeth and bones are sometimes stained purple as a result of ingesting sea urchins. The sea otter has a metabolic rate two or three times that of comparatively sized terrestrial mammals. It must eat an estimated 25 to 38% of its own body weight in food each day to burn the calories necessary to counteract the loss of heat due to the cold water environment. Its digestive efficiency is estimated at 80 to 85%, and food is digested and passed in as little as three hours. Most of its need for water is met through food, although, in contrast to most other marine mammals, it also drinks seawater. Its relatively large kidneys enable it to derive fresh water from sea water and excrete concentrated urine.

Behavior

The sea otter is diurnal. It has a period of foraging and eating in the morning, starting about an hour before sunrise, then rests or sleeps in mid-day. Foraging resumes for a few hours in the afternoon and subsides before sunset, and a third foraging period may occur around midnight. Females with pups appear to be more inclined to feed at night. Observations of the amount of time a sea otter must spend each day foraging range from 24 to 60%, apparently depending on the availability of food in the area.

Sea otters spend much of their time grooming, which consists of cleaning the fur, untangling knots, removing loose fur, rubbing the fur to squeeze out water and introduce air, and blowing air into the fur. To casual observers, it appears as if the animals are scratching, but they are not known to have lice or other parasites in the fur. When eating, sea otters roll in the water frequently, apparently to wash food scraps from their fur.

Foraging

See also: Physiology of underwater divingThe sea otter hunts in short dives, often to the sea floor. Although it can hold its breath for up to five minutes, its dives typically last about one minute and not more than four minutes. It is the only marine animal capable of lifting and turning over rocks, which it often does with its front paws when searching for prey. The sea otter may also pluck snails and other organisms from kelp and dig deep into underwater mud for clams. It is the only marine mammal that catches fish with its forepaws rather than with its teeth. A Misplaced Pages editor has observed Otters pulling clusters of gooseneck barnacles and mussels from piers at the wharf in Santa Cruz, California.

Under each foreleg, the sea otter has a loose pouch of skin that extends across the chest. In this pouch (preferentially the left one), the animal stores collected food to bring to the surface. This pouch also holds a rock, unique to the otter, that is used to break open shellfish and clams. At the surface, the sea otter eats while floating on its back, using its forepaws to tear food apart and bring it to its mouth. It can chew and swallow small mussels with their shells, whereas large mussel shells may be twisted apart. It uses its lower incisor teeth to access the meat in shellfish. To eat large sea urchins, which are mostly covered with spines, the sea otter bites through the underside where the spines are shortest, and licks the soft contents out of the urchin's shell.

The sea otter's use of rocks when hunting and feeding makes it one of the few mammal species to use tools. To open hard shells, it may pound its prey with both paws against a rock on its chest. To pry an abalone off its rock, it hammers the abalone shell using a large stone, with observed rates of 45 blows in 15 seconds. Releasing an abalone, which can cling to rock with a force equal to 4,000 times its own body weight, requires multiple dives.

Social structure

Although each adult and independent juvenile forages alone, sea otters tend to rest together in single-sex groups called rafts. A raft typically contains 10 to 100 animals, with male rafts being larger than female ones. The largest raft ever seen contained over 2000 sea otters. To keep themselves from drifting out to sea when resting and eating, sea otters may wrap themselves in kelp.

A male sea otter is most likely to mate if he maintains a breeding territory in an area that is also favored by females. As autumn is the peak breeding season in most areas, males typically defend their territory only from spring to autumn. During this time, males patrol the boundaries of their territories to exclude other males, although actual fighting is rare. Adult females move freely between male territories, where they outnumber adult males by an average of five to one. Males that do not have territories tend to congregate in large, male-only groups, and swim through female areas when searching for a mate.

The species exhibits a variety of vocal behaviors. The cry of a pup is often compared to that of a gull. Females coo when they are apparently content; males may grunt instead. Distressed or frightened adults may whistle, hiss, or in extreme circumstances, scream. Although sea otters can be playful and sociable, they are not considered to be truly social animals. They spend much time alone, and each adult can meet its own hunting, grooming, and defense needs.

Reproduction and life cycle

Sea otters are polygynous: males have multiple female partners, typically those that inhabit their territory. If no territory is established, they seek out females in estrus. When a male sea otter finds a receptive female, the two engage in playful and sometimes aggressive behavior. They bond for the duration of estrus, or 3 days. The male holds the female's head or nose with his jaws during copulation. Visible scars are often present on females from this behavior.

Births occur year-round, with peaks between May and June in northern populations and between January and March in southern populations. Gestation appears to vary from four to twelve months, as the species is capable of delayed implantation followed by four months of pregnancy. In California, sea otters usually breed every year, about twice as often as those in Alaska.

Birth usually takes place in the water and typically produces a single pup weighing 1.4 to 2.3 kilograms (3 lb 1 oz to 5 lb 1 oz). Twins occur in 2% of births; however, usually only one pup survives. At birth, the eyes are open, ten teeth are visible, and the pup has a thick coat of baby fur. Mothers have been observed to lick and fluff a newborn for hours; after grooming, the pup's fur retains so much air, the pup floats like a cork and cannot dive. The fluffy baby fur is replaced by adult fur after about 13 weeks.

Nursing lasts six to eight months in Californian populations and four to twelve months in Alaska, with the mother beginning to offer bits of prey at one to two months. The milk from a sea otter's two abdominal nipples is rich in fat and more similar to the milk of other marine mammals than to that of other mustelids. A pup, with guidance from its mother, practices swimming and diving for several weeks before it is able to reach the sea floor. Initially, the objects it retrieves are of little food value, such as brightly colored starfish and pebbles. Juveniles are typically independent at six to eight months, but a mother may be forced to abandon a pup if she cannot find enough food for it; at the other extreme, a pup may be nursed until it is almost adult size. Pup mortality is high, particularly during an individual's first winter – by one estimate, only 25% of pups survive their first year. Pups born to experienced mothers have the highest survival rates.

Females perform all tasks of feeding and raising offspring, and have occasionally been observed caring for orphaned pups. Much has been written about the level of devotion of sea otter mothers for their pups – a mother gives her infant almost constant attention, cradling it on her chest away from the cold water and attentively grooming its fur. When foraging, she leaves her pup floating on the water, sometimes wrapped in kelp to keep it from floating away; if the pup is not sleeping, it cries loudly until she returns. Mothers have been known to carry their pups for days after the pups' deaths.

Females become sexually mature at around three or four years of age and males at around five; however, males often do not successfully breed until a few years later. A captive male sired offspring at age 19. In the wild, sea otters live to a maximum age of 23 years, with lifespans ranging from 10 to 15 years for males and 15–20 years for females. Several captive individuals have lived past 20 years. The Seattle Aquarium was home to both the oldest recorded female, Etika, who lived to the age of 28, and the oldest recorded male, Adaa, who lived to be 22 years 8 months. Sea otters in the wild often develop worn teeth, which may account for their apparently shorter lifespans.

Population and distribution

Sea otters live in coastal waters 15 to 23 metres (49 to 75 ft) deep, and usually stay within a kilometre (2⁄3 mi) of the shore. They are found most often in areas with protection from the most severe ocean winds, such as rocky coastlines, thick kelp forests, and barrier reefs. Although they are most strongly associated with rocky substrates, sea otters can also live in areas where the sea floor consists primarily of mud, sand, or silt. Their northern range is limited by ice, as sea otters can survive amidst drift ice but not land-fast ice. Individuals generally occupy a home range a few kilometres long, and remain there year-round.

The sea otter population is thought to have once been 150,000 to 300,000, stretching in an arc across the North Pacific from northern Japan to the central Baja California Peninsula in Mexico. The fur trade that began in the 1740s reduced the sea otter's numbers to an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 members in 13 colonies. Hunting records researched by historian Adele Ogden place the westernmost limit of the hunting grounds off the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido and the easternmost limit off Punta Morro Hermosa about 21+1⁄2 miles (34.6 km) south of Punta Eugenia, Baja California's westernmost headland in Mexico.

In about two-thirds of its former range, the species is at varying levels of recovery, with high population densities in some areas and threatened populations in others. Sea otters currently have stable populations in parts of the Russian east coast, Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, and California, with reports of recolonizations in Mexico and Japan. Population estimates made between 2004 and 2007 give a worldwide total of approximately 107,000 sea otters.

Japan

Adele Ogden wrote in The California Sea Otter Trade that western sea otter were hunted "from Yezo northeastward past the Kuril Group and Kamchatka to the Aleutian Chain". "Yezo" refers to the island province of Hokkaido, in northern Japan, where the country's only confirmed population of western sea otter resides. Sightings have been documented in the waters of Cape Nosappu, Erimo, Hamanaka and Nemuro, among other locations in the region.

Russia

Currently, the most stable and secure part of the western sea otter's range is along the Russian Far East coastline, in the northwestern Pacific waters off of the country (namely Kamchatka and Sakhalin Island), occasionally being seen in and around the Sea of Okhotsk. Before the 19th century, around 20,000 to 25,000 sea otters lived near the Kuril Islands, with more near Kamchatka and the Commander Islands. After the years of the Great Hunt, the population in these areas, currently part of Russia, was only 750. By 2004, sea otters had repopulated all of their former habitat in these areas, with an estimated total population of about 27,000. Of these, about 19,000 are at the Kurils, 2,000 to 3,500 at Kamchatka and another 5,000 to 5,500 at the Commander Islands. Growth has slowed slightly, suggesting the numbers are reaching carrying capacity.

British Columbia

Along the North American coast south of Alaska, the sea otter's range is discontinuous. A remnant population survived off Vancouver Island into the 20th century, but it died out despite the 1911 international protection treaty, with the last sea otter taken near Kyuquot in 1929. From 1969 to 1972, 89 sea otters were flown or shipped from Alaska to the west coast of Vancouver Island. This population increased to over 5,600 in 2013 with an estimated annual growth rate of 7.2%, and their range on the island's west coast extended north to Cape Scott and across the Queen Charlotte Strait to the Broughton Archipelago and south to Clayoquot Sound and Tofino. In 1989, a separate colony was discovered in the central British Columbia coast. It is not known if this colony, which numbered about 300 animals in 2004, was founded by transplanted otters or was a remnant population that had gone undetected. By 2013, this population exceeded 1,100 individuals, was increasing at an estimated 12.6% annual rate, and its range included Aristazabal Island, and Milbanke Sound south to Calvert Island. In 2008, Canada determined the status of sea otters to be "special concern".

United States

Alaska

Alaska is the central area of the sea otter's range. In 1973, the population in Alaska was estimated at between 100,000 and 125,000 animals. By 2006, though, the Alaska population had fallen to an estimated 73,000 animals. A massive decline in sea otter populations in the Aleutian Islands accounts for most of the change; the cause of this decline is not known, although orca predation is suspected. The sea otter population in Prince William Sound was also hit hard by the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which killed thousands of sea otters in 1989.

Washington

In 1969 and 1970, 59 sea otters were translocated from Amchitka Island to Washington, and released near La Push and Point Grenville. The translocated population is estimated to have declined to between 10 and 43 individuals before increasing, reaching 208 individuals in 1989. As of 2017, the population was estimated at over 2,000 individuals, and their range extends from Point Grenville in the south to Cape Flattery in the north and east to Pillar Point along the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

In Washington, sea otters are found almost exclusively on the outer coasts. They can swim as close as six feet off shore along the Olympic coast. Reported sightings of sea otters in the San Juan Islands and Puget Sound almost always turn out to be North American river otters, which are commonly seen along the seashore. However, biologists have confirmed isolated sightings of sea otters in these areas since the mid-1990s.

Oregon

The last native sea otter in Oregon was probably shot and killed in 1906. In 1970 and 1971, a total of 95 sea otters were transplanted from Amchitka Island, Alaska to the Southern Oregon coast. However, this translocation effort failed and otters soon again disappeared from the state. In 2004, a male sea otter took up residence at Simpson Reef off of Cape Arago for six months. This male is thought to have originated from a colony in Washington, but disappeared after a coastal storm. On 18 February 2009, a male sea otter was spotted in Depoe Bay off the Oregon Coast. It could have traveled to the state from either California or Washington.

California

The historic population of California sea otters was estimated at 16,000 before the fur trade decimated the population, leading to their assumed extinction. Today's population of California sea otters are the descendants of a single colony of about 50 sea otters located near Bixby Creek Bridge in March 1938. Their principal range has gradually expanded and extends from Pigeon Point in San Mateo County to Santa Barbara County.

Sea otters were once numerous in San Francisco Bay. Historical records revealed the Russian-American Company snuck Aleuts into San Francisco Bay multiple times, despite the Spanish capturing or shooting them while hunting sea otters in the estuaries of San Jose, San Mateo, San Bruno and around Angel Island. The founder of Fort Ross, Ivan Kuskov, finding otters scarce on his second voyage to Bodega Bay in 1812, sent a party of Aleuts to San Francisco Bay, where they met another Russian party and an American party, and caught 1,160 sea otters in three months. By 1817, sea otters in the area were practically eliminated and the Russians sought permission from the Spanish and the Mexican governments to hunt further and further south of San Francisco. In 1833, fur trappers George Nidever and George Yount canoed "along the Petaluma side of Bay, and then proceeded to the San Joaquin River", returning with sea otter, beaver, and river otter pelts. Remnant sea otter populations may have survived in the bay until 1840, when the Rancho Punta de Quentin was granted to Captain John B. R. Cooper, a sea captain from Boston, by Mexican Governor Juan Bautista Alvarado along with a license to hunt sea otters, reportedly then prevalent at the mouth of Corte Madera Creek.

In the late 1980s, the USFWS relocated about 140 southern sea otters to San Nicolas Island in southern California, in the hope of establishing a reserve population should the mainland be struck by an oil spill. To the surprise of biologists, the majority of the San Nicolas sea otters swam back to the mainland. Another group of twenty swam 74 miles (119 km) north to San Miguel Island, where they were captured and removed. By 2005, only 30 sea otters remained at San Nicolas, although they were slowly increasing as they thrived on the abundant prey around the island. The plan that authorized the translocation program had predicted the carrying capacity would be reached within five to 10 years. The spring 2016 count at San Nicolas Island was 104 sea otters, continuing a 5-year positive trend of over 12% per year. Sea otters were observed twice in Southern California in 2011, once near Laguna Beach and once at Zuniga Point Jetty, near San Diego. These are the first documented sightings of otters this far south in 30 years.

When the USFWS implemented the translocation program, it also attempted, in 1986, to implement "zonal management" of the Californian population. To manage the competition between sea otters and fisheries, it declared an "otter-free zone" stretching from Point Conception to the Mexican border. In this zone, only San Nicolas Island was designated as sea otter habitat, and sea otters found elsewhere in the area were supposed to be captured and relocated. These plans were abandoned after many translocated otters died and also as it proved impractical to capture the hundreds of otters which ignored regulations and swam into the zone. However, after engaging in a period of public commentary in 2005, the Fish and Wildlife Service failed to release a formal decision on the issue. Then, in response to lawsuits filed by the Santa Barbara-based Environmental Defense Center and the Otter Project, on 19 December 2012 the USFWS declared that the "no otter zone" experiment was a failure, and will protect the otters re-colonizing the coast south of Point Conception as threatened species. Although abalone fisherman blamed the incursions of sea otters for the decline of abalone, commercial abalone fishing in southern California came to an end from overfishing in 1997, years before significant otter moved south of Point Conception. In addition, white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni), a species never overlapping with sea otter, had declined in numbers 99% by 1996, and became the first marine invertebrate to be federally listed as endangered.

Although the southern sea otter's range has continuously expanded from the remnant population of about 50 individuals in Big Sur since protection in 1911, from 2007 to 2010, the otter population and its range contracted and since 2010 has made little progress. As of spring 2010, the northern boundary had moved from about Tunitas Creek to a point 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) southeast of Pigeon Point, and the southern boundary has moved along the Gaviota Coast from approximately Coal Oil Point to Gaviota State Park. A toxin called microcystin, produced by a type of cyanobacteria (Microcystis), seems to be concentrated in the shellfish the otters eat, poisoning them. Cyanobacteria are found in stagnant water enriched with nitrogen and phosphorus from septic tank and agricultural fertilizer runoff, and may be flushed into the ocean when streamflows are high in the rainy season. A record number of sea otter carcasses were found on California's coastline in 2010, with increased shark attacks an increasing component of the mortality. Great white sharks do not consume relatively fat-poor sea otters but shark-bitten carcasses have increased from 8% in the 1980s to 15% in the 1990s and to 30% in 2010 and 2011.

For southern sea otters to be considered for removal from threatened species listing, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) determined that the population should exceed 3,090 for three consecutive years. In response to recovery efforts, the population climbed steadily from the mid-20th century through the early 2000s, then remained relatively flat from 2005 to 2014 at just under 3,000. There was some contraction from the northern (now Pigeon Point) and southern limits of the sea otter's range during the end of this period, circumstantially related to an increase in lethal shark bites, raising concerns that the population had reached a plateau. However, the population increased markedly from 2015 to 2016, with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) California sea otter survey 3-year average reaching 3,272 in 2016, the first time it exceeded the threshold for delisting from the Endangered Species Act (ESA). If populations continued to grow and ESA delisting occurred, southern sea otters would still be fully protected by state regulations and the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which set higher thresholds for protection, at approximately 8,400 individuals. However, ESA delisting seems unlikely due to a precipitous population decline recorded in the spring 2017 USGS sea otter survey count, from the 2016 high of 3,615 individuals to 2,688, a loss of 25% of the California sea otter population.

Mexico

Historian Adele Ogden described sea otters as being particularly abundant in "Lower California", now the Baja California Peninsula, where "seven bays...were main centers". The southernmost limit was Punta Morro Hermoso about 21+1⁄2 miles (34.6 km) south of Punta Eugenia, in turn a headland at the southwestern end of Sebastián Vizcaíno Bay, on the west coast of the Baja Peninsula. Otter were also taken from San Benito Island, Cedros Island, and Isla Natividad in the Bay. By the early 1900s, Baja's sea otters were extirpated by hunting. In a 1997 survey, small numbers of sea otters, including pups, were reported by local fishermen, but scientists could not confirm these accounts. However, male and female otters have been confirmed by scientists off shores of the Baja Peninsula in a 2014 study, who hypothesize that otter dispersed there beginning in 2005. These sea otters may have dispersed from San Nicolas Island, which is 300 kilometres (190 mi) away, as individuals have been recorded traversing distances of over 800 kilometres (500 mi). Genetic analysis of most of these animals were consistent with California, i.e. United States, otter origins, however one otter had a haplotype not previously reported, and could represent a remnant of the original native Mexican otter population.

Ecology

Diet

High energetic requirements of sea otter metabolism require them to consume at least 20% of their body weight a day. Surface swimming and foraging are major factors in their high energy expenditure due to drag on the surface of the water when swimming and the thermal heat loss from the body during deep dives when foraging. Sea otter muscles are specially adapted to generate heat without physical activity.

Sea otters are apex predators that consume over 100 prey species.In most of its range, the sea otter's diet consists almost exclusively of marine benthic invertebrates, including sea urchins (such as Strongylocentrotus franciscanus and S. purpuratus), sea cucumbers, fat innkeeper worms, crustaceans, a variety of mollusks such as chitons (such as Katharina tunicata), snails such as abalones and limpets (such as Diodora aspera), and bivalves such as clams, mussels (such as Mytilus edulis), and scallops (such as Crassadoma gigantea). Its prey ranges in size from tiny limpets and crabs to giant octopuses. Where prey such as sea urchins, clams, and abalone are present in a range of sizes, sea otters tend to select larger items over smaller ones of similar type. In California, they have been noted to ignore Pismo clams smaller than 3 inches (76 mm) across.

In a few northern areas, fish are also eaten. In studies performed at Amchitka Island in the 1960s, where the sea otter population was at carrying capacity, 50% of food found in sea otter stomachs was fish. The fish species were usually bottom-dwelling and sedentary or sluggish forms, such as Hemilepidotus hemilepidotus and family Tetraodontidae. However, south of Alaska on the North American coast, fish are a negligible or extremely minor part of the sea otter's diet. Contrary to popular depictions, sea otters rarely eat starfish, and any kelp that is consumed apparently passes through the sea otter's system undigested. Sea otters will also occasionally prey on seabirds. In California, the most commonly eaten species were western grebes, although cormorants, gulls, common loons, and surf scoters were also consumed.

The individuals within a particular area often differ in their foraging methods and prey types, and tend to follow the same patterns as their mothers. The diet of local populations also changes over time, as sea otters can significantly deplete populations of highly preferred prey such as large sea urchins, and prey availability is also affected by other factors such as fishing by humans. Sea otters can thoroughly remove abalone from an area except for specimens in deep rock crevices, however, they never completely wipe out a prey species from an area. A 2007 Californian study demonstrated, in areas where food was relatively scarce, a wider variety of prey was consumed. Surprisingly, though, the diets of individuals were more specialized in these areas than in areas where food was plentiful.

As a keystone species

Sea otters are a classic example of a keystone species; their presence affects the ecosystem more profoundly than their size and numbers would suggest. They keep the population of certain benthic (sea floor) herbivores, particularly sea urchins, in check. Sea urchins graze on the lower stems of kelp, causing the kelp to drift away and die. Loss of the habitat and nutrients provided by kelp forests leads to profound cascade effects on the marine ecosystem. North Pacific areas that do not have sea otters often turn into urchin barrens, with abundant sea urchins and no kelp forest. Kelp forests are extremely productive ecosystems. Kelp forests sequester (absorb and capture) CO2 from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. Sea otters may help mitigate effects of climate change by their cascading trophic influence.

Reintroduction of sea otters to British Columbia has led to a dramatic improvement in the health of coastal ecosystems, and similar changes have been observed as sea otter populations recovered in the Aleutian and Commander Islands and the Big Sur coast of California. However, some kelp forest ecosystems in California have also thrived without sea otters, with sea urchin populations apparently controlled by other factors. The role of sea otters in maintaining kelp forests has been observed to be more important in areas of open coast than in more protected bays and estuaries.

Sea otters affect rocky ecosystems that are dominated by mussel beds by removing mussels from rocks. This allows space for competing species and increases species diversity.

Predators

The leading mammalian predators of this species is the orca. Sea lions and bald eagles may prey on pups. On land, young sea otters may face attack from bears and coyotes. In California, great white sharks are their primary predator, though this is the result of mistaking otters for seals and they do not consume otters after biting them. In Katmai National Park, grey wolves have been recorded to hunt and kill sea otters.

Urban runoff transporting cat feces into the ocean brings Toxoplasma gondii, an obligate parasite of felids, which has killed sea otters. Parasitic infections of Sarcocystis neurona are also associated with human activity. According to the U.S. Geological Survey and the CDC, northern sea otters off Washington have been infected with the H1N1 flu virus and "may be a newly identified animal host of influenza viruses".

Relationship with humans

Fur trade

Sea otters have the thickest fur of any mammal, which makes them a common target for many hunters. Archaeological evidence indicates that for thousands of years, indigenous peoples have hunted sea otters for food and fur. Large-scale hunting, part of the Maritime Fur Trade, which would eventually kill approximately one million sea otters, began in the 18th century when hunters and traders began to arrive from all over the world to meet foreign demand for otter pelts, which were one of the world's most valuable types of fur.

In the early 18th century, Russians began to hunt sea otters in the Kuril Islands and sold them to the Chinese at Kyakhta. Russia was also exploring the far northern Pacific at this time, and sent Vitus Bering to map the Arctic coast and find routes from Siberia to North America. In 1741, on his second North Pacific voyage, Bering was shipwrecked off Bering Island in the Commander Islands, where he and many of his crew died. The surviving crew members, which included naturalist Georg Steller, discovered sea otters on the beaches of the island and spent the winter hunting sea otters and gambling with otter pelts. They returned to Siberia, having killed nearly 1,000 sea otters, and were able to command high prices for the pelts. Thus began what is sometimes called the "Great Hunt", which would continue for another hundred years. The Russians found the sea otter far more valuable than the sable skins that had driven and paid for most of their expansion across Siberia. If the sea otter pelts brought back by Bering's survivors had been sold at Kyakhta prices they would have paid for one tenth the cost of Bering's expedition.

Russian fur-hunting expeditions soon depleted the sea otter populations in the Commander Islands, and by 1745, they began to move on to the Aleutian Islands. The Russians initially traded with the Aleuts inhabitants of these islands for otter pelts, but later enslaved the Aleuts, taking women and children hostage and torturing and killing Aleut men to force them to hunt. Many Aleuts were either murdered by the Russians or died from diseases the hunters had introduced. The Aleut population was reduced, by the Russians' own estimate, from 20,000 to 2,000. By the 1760s, the Russians had reached Alaska. In 1799, Tsar Paul I consolidated the rival fur-hunting companies into the Russian-American Company, granting it an imperial charter and protection, and a monopoly over trade rights and territorial acquisition. Under Aleksander I, the administration of the merchant-controlled company was transferred to the Imperial Navy, largely due to the alarming reports by naval officers of native abuse; in 1818, the indigenous peoples of Alaska were granted civil rights equivalent to a townsman status in the Russian Empire.

Other nations joined in the hunt in the south. Along the coasts of what is now Mexico and California, Spanish explorers bought sea otter pelts from Native Americans and sold them in Asia. In 1778, British explorer Captain James Cook reached Vancouver Island and bought sea otter furs from the First Nations people. When Cook's ship later stopped at a Chinese port, the pelts rapidly sold at high prices, and were soon known as "soft gold". As word spread, people from all over Europe and North America began to arrive in the Pacific Northwest to trade for sea otter furs.

Russian hunting expanded to the south, initiated by American ship captains, who subcontracted Russian supervisors and Aleut hunters in what are now Washington, Oregon, and California. Between 1803 and 1846, 72 American ships were involved in the otter hunt in California, harvesting an estimated 40,000 skins and tails, compared to only 13 ships of the Russian-American Company, which reported 5,696 otter skins taken between 1806 and 1846. In 1812, the Russians founded an agricultural settlement at what is now Fort Ross in northern California, as their southern headquarters. Eventually, sea otter populations became so depleted, commercial hunting was no longer viable. It had stopped in the Aleutian Islands, by 1808, as a conservation measure imposed by the Russian-American Company. Further restrictions were ordered by the company in 1834. When Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Alaska population had recovered to over 100,000, but Americans resumed hunting and quickly extirpated the sea otter again. Prices rose as the species became rare. During the 1880s, a pelt brought $105 to $165 in the London market, but by 1903, a pelt could be worth as much as $1,125. In 1911, Russia, Japan, Great Britain (for Canada) and the United States signed the Treaty for the Preservation and Protection of Fur Seals, imposing a moratorium on the harvesting of sea otters. So few remained, perhaps only 1,000–2,000 individuals in the wild, that many believed the species would become extinct.

Recovery and conservation

Main article: Sea otter conservation

During the 20th century, sea otter numbers rebounded in about two-thirds of their historic range, a recovery considered one of the greatest successes in marine conservation. However, the IUCN still lists the sea otter as an endangered species, and describes the significant threats to sea otters as oil pollution, predation by orcas, poaching, and conflicts with fisheries – sea otters can drown if entangled in fishing gear. The hunting of sea otters is no longer legal except for limited harvests by indigenous peoples in the United States. Poaching was a serious concern in the Russian Far East immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; however, it has declined significantly with stricter law enforcement and better economic conditions.

The most significant threat to sea otters is oil spills, to which they are particularly vulnerable, since they rely on their fur to keep warm. When their fur is soaked with oil, it loses its ability to retain air, and the animals can quickly die from hypothermia. The liver, kidneys, and lungs of sea otters also become damaged after they inhale oil or ingest it when grooming. The Exxon Valdez oil spill of 24 March 1989 killed thousands of sea otters in Prince William Sound, and as of 2006, the lingering oil in the area continues to affect the population. Describing the public sympathy for sea otters that developed from media coverage of the event, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service spokesperson wrote:

As a playful, photogenic, innocent bystander, the sea otter epitomized the role of victim ... cute and frolicsome sea otters suddenly in distress, oiled, frightened, and dying, in a losing battle with the oil.

The small geographic ranges of the sea otter populations in California, Washington, and British Columbia mean a single major spill could be catastrophic for that state or province. Prevention of oil spills and preparation to rescue otters if one happens is a major focus for conservation efforts. Increasing the size and range of sea otter populations would also reduce the risk of an oil spill wiping out a population. However, because of the species' reputation for depleting shellfish resources, advocates for commercial, recreational, and subsistence shellfish harvesting have often opposed allowing the sea otter's range to increase, and there have even been instances of fishermen and others illegally killing them. With a population size of fifty, the low genetic diversity amongst the population post-fur trade but pre-discovery produced an evolutionary bottleneck. The recent population constraints put on the sea otter have led to low genomic diversity among species members, with much evidence of inbreeding. This inbreeding has led to the mutation of deleterious missense mutations, which may make fast-paced population growth difficult for conservation reasons. While longer-term recovery goals bolstering genetic diversity by inbreeding are costly and challenging, they could significantly aid in avoiding the further evolution of deleterious variation, thus aiding sea otter population stabilization. This method has already been utilized in returning cheetah populations to higher numbers and higher genetic diversity, and captive breeding programs through organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium and The Marine Mammal Center make the chances of getting sea otter populations back up to pre-fur trade numbers possible. The population of sea otters in California has risen to around 3,000 in the wild. While this figure is far below pre-fur trade numbers, it represents a massive improvement in the conservation of the species and a massive increase in genetic diversity. On the other hand, northern sea otters have reached back up to pre-fur trade population numbers, with populations living all along the state's coast from Ketchikan in the south to Attu in the west. Historical populations, however, are estimated to have been between 150,000 and 300,000 individuals living along the northern Pacific rim from Baja California to Hokkaido Island in Japan. Modern conservation techniques have included breeding northern and southern populations of sea otters to increase genetic diversity and prevent both inbreeding and genetic drift. Moreover, the introduction of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in the 1970s made their hunting highly illegal in the United States.

In the Aleutian Islands, a massive and unexpected disappearance of sea otters has occurred in recent decades. In the 1980s, the area was home to an estimated 55,000 to 100,000 sea otters, but the population fell to around 6,000 animals by 2000. The most widely accepted, but still controversial, hypothesis is that killer whales have been eating the otters. The pattern of disappearances is consistent with a rise in predation, but there has been no direct evidence of orcas preying on sea otters to any significant extent. Another area of concern is California, where recovery began to fluctuate or decline in the late 1990s. Unusually high mortality rates amongst adult and subadult otters, particularly females, have been reported. In 2017 the US Geological Survey found a 3% drop in the sea otter population of the California coast. This number still keeps them on track for removal from the endangered species list, although just barely. Necropsies of dead sea otters indicate diseases, particularly Toxoplasma gondii and acanthocephalan parasite infections, are major causes of sea otter mortality in California. The Toxoplasma gondii parasite, which is often fatal to sea otters, is carried by wild and domestic cats and may be transmitted by domestic cat droppings flushed into the ocean via sewage systems. Although disease has clearly contributed to the deaths of many of California's sea otters, it is not known why the California population is apparently more affected by disease than populations in other areas.

Sea otter habitat is preserved through several protected areas in the United States, Russia and Canada. In marine protected areas, polluting activities such as dumping of waste and oil drilling are typically prohibited. An estimated 1,200 sea otters live within the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and more than 500 live within the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary.

Economic impact

Some of the sea otter's preferred prey species, particularly abalone, clams, and crabs, are also food sources for humans. In some areas, massive declines in shellfish harvests have been blamed on the sea otter, and intense public debate has taken place over how to manage the competition between sea otters and humans for seafood.

The debate is complicated because sea otters have sometimes been held responsible for declines of shellfish stocks that were more likely caused by overfishing, disease, pollution, and seismic activity. Shellfish declines have also occurred in many parts of the North American Pacific coast that do not have sea otters, and conservationists sometimes note the existence of large concentrations of shellfish on the coast is a recent development resulting from the fur trade's near-extirpation of the sea otter. Although many factors affect shellfish stocks, sea otter predation can deplete a fishery to the point where it is no longer commercially viable. Scientists agree that sea otters and abalone fisheries cannot exist in the same area, and the same is likely true for certain other types of shellfish, as well.

Many facets of the interaction between sea otters and the human economy are not as immediately felt. Sea otters have been credited with contributing to the kelp harvesting industry via their well-known role in controlling sea urchin populations; kelp is used in the production of diverse food and pharmaceutical products. Although human divers harvest red sea urchins both for food and to protect the kelp, sea otters hunt more sea urchin species and are more consistently effective in controlling these populations. E. lutris is a controlling predator of the red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus) in the Bering Sea, which would otherwise be out of control as it is in its invasive range, the Barents Sea. (Berents otters, Lutra lutra, occupy the same ecological niche and so are believed to help to control them in the Berents but this has not been studied.) The health of the kelp forest ecosystem is significant in nurturing populations of fish, including commercially important fish species. In some areas, sea otters are popular tourist attractions, bringing visitors to local hotels, restaurants, and sea otter-watching expeditions.

Roles in human cultures

|

Left: Aleut sea otter amulet in the form of a mother with pup. Above: Aleut carving of a sea otter hunt on a whalebone spear. Both items are on display at the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg. Articles depicting sea otters were considered to have magical properties. |

For many maritime indigenous cultures throughout the North Pacific, especially the Ainu in the Kuril Islands, the Koryaks and Itelmen of Kamchatka, the Aleut in the Aleutian Islands, the Haida of Haida Gwaii and a host of tribes on the Pacific coast of North America, the sea otter has played an important role as a cultural, as well as material, resource. These cultures, many of which have strongly animist traditions full of legends and stories in which many aspects of the natural world are associated with spirits, regarded the sea otter as particularly kin to humans. The Nuu-chah-nulth, Haida, and other First Nations of coastal British Columbia used the warm and luxurious pelts as chiefs' regalia. Sea-otter pelts were given in potlatches to mark coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. The Aleuts carved sea otter bones for use as ornaments and in games, and used powdered sea-otter baculum as a medicine for fever.

Some Ainu folk-tales portray the sea-otter as an occasional messenger between humans and the creator. The sea otter is a recurring figure in Ainu folklore. A major Ainu epic, the Kutune Shirka, tells the tale of wars and struggles over a golden sea-otter. Versions of a widespread Aleut legend tell of lovers or despairing women who plunge into the sea and become otters. These stories have been associated with the many human-like behavioral features of the sea otter, including apparent playfulness, strong mother-pup bonds and tool use, yielding to ready anthropomorphism. The beginning of commercial exploitation had a great impact on the human, as well as animal, populations. The Ainu and Aleuts have been displaced or their numbers are dwindling, while the coastal tribes of North America, where the otter is in any case greatly depleted, no longer rely as intimately on sea mammals for survival.

Since the mid-1970s, the beauty and charisma of the species have gained wide appreciation, and the sea otter has become an icon of environmental conservation. The round, expressive face and soft, furry body of the sea otter are depicted in a wide variety of souvenirs, postcards, clothing, and stuffed toys.

Aquariums and zoos

Sea otters can do well in captivity, and are featured in over 40 public aquariums and zoos. The Seattle Aquarium became the first institution to raise sea otters from conception to adulthood with the birth of Tichuk in 1979, followed by three more pups in the early 1980s. In 2007, a YouTube video of two sea otters holding paws drew 1.5 million viewers in two weeks, and had over 22 million views as of July 2022. Filmed five years previously at the Vancouver Aquarium, it was YouTube's most popular animal video at the time, although it has since been surpassed. The lighter-colored otter in the video is Nyac, a survivor of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. Nyac died in September 2008, at the age of 20. Milo, the darker one, died of lymphoma in January 2012.

Other sea otters at the Vancouver Aquarium have also gone viral. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the livestream of Joey, a rescued sea otter pup at the Marine Mammal Rescue Center, attracted millions of viewers from across the world on YouTube and Twitch. Many viewers said the stream helped them cope with the anxiety and depression caused by the pandemic lockdowns. In June 2024, a video of another rescued sea otter pup, Tofino, received over 120,000,000 views and 5,000,000 likes on Instagram.

Beginning in 2019, the streamer Douglas Wreden, popularly known as DougDoug, has held charity streams for the Monterey Bay Aquarium to celebrate the birthday of Rosa the sea otter. As of 2024, DougDoug and his community have raised over $1,000,000 in Rosa's name.

Current conservation

Sea otters, being a known keystone species, need a humanitarian effort to be protected from endangerment through "unregulated human exploitation". This species has increasingly been impacted by the large oil spills and environmental degradation caused by overfishing and entanglement in fishing gear. Current efforts have been made in legislation: the international Fur Seal Treaty, The Endangered Species Act, IUCN/The World Conservation Union, Convention on international Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. Other conservation efforts are done through reintroduction and zoological parks.

Sea Otter Awareness Week is held every year during the last full week of September. Zoos, aquariums, and other educational institutions hold events highlighting sea otters, their ecological importance, and the challenges facing their conservation. It is organized and sponsored by Defenders of Wildlife, the Monterey Bay Aquarium, the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sea Otter Savvy, and the Elakha Alliance.

See also

Notes

- Enhydra lutris nereis is included in Appendix I

References

Citations

- ^ Doroff, A.; Burdin, A. (2015). "Enhydra lutris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T7750A21939518. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T7750A21939518.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- "The secret life of otters". www.montereybayaquarium.org. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Womble, Jamie (29 July 2016). "A Keystone Species, the Sea Otter, Colonizes Glacier Bay". National Park Service. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Riedman, M.L.; Estes, James A. (1990). The sea otter (Enhydra lutris): behavior, ecology, and natural history. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report (Report). Washington, D.C. p. 126. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Enhydra lutris". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Kenyon, p. 4

- ^ VanBlaricom, p. 11

- Koepfli, K.-P.; Wayne, R. K. (December 1998). "Phylogenetic relationships of otters (Carnivora: Mustelidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Journal of Zoology. 246 (4): 401–416. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00172.x.

- Koepfli KP; Deere KA; Slater GJ; et al. (2008). "Multigene phylogeny of the Mustelidae: resolving relationships, tempo and biogeographic history of a mammalian adaptive radiation". BMC Biology. 6: 10. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-10. PMC 2276185. PMID 18275614.

- ^ Love, p. 9

- Willemsen GF (1992). "A revision of the Pliocene and Quaternary Lutrinae from Europe". Scripta Geologica. 101: 1–115. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.738.4492.

- Love, pp. 15–16

- Love, pp. 4–6

- Love, p. 6

- ^ Jones, Samantha J; Haulena, Martin; Taylor, Gregory A; Chan, Simon; Bilobram, Steven; Warren, René L; Hammond, Austin; Mungall, Karen L; Choo, Caleb; et al. (11 December 2017). "The Genome of the Northern Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni)". Genes. 8 (12): 379. doi:10.3390/genes8120379. PMC 5748697. PMID 29232880.

- ^ Beichman, Annabel C; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Li, Gang; Murphy, William; Dobrynin, Pasha; Kliver, Sergei; Tinker, Martin T; Murray, Michael J; Johnson, Jeremy; Lindblad-Toh, Kerstin; Karlsson, Elinor K; Lohmueller, Kirk E; Wayne, Robert K (December 2019). "Aquatic Adaptation and Depleted Diversity: A Deep Dive into the Genomes of the Sea Otter and Giant Otter". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (12): 2631–2655. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz101. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 7967881. PMID 31212313.

- ^ Larson, Shawn; Jameson, Ron; Etnier, Michael; Jones, Terry; Hall, Roberta (5 March 2012). "Genetic Diversity and Population Parameters of Sea Otters, Enhydra lutris, before Fur Trade Extirpation from 1741–1911". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e32205. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732205L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032205. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3293891. PMID 22403635.

- Koepfli KP, Deere KA, Slater GJ, et al. (2008). "Multigene phylogeny of the Mustelidae: Resolving relationships, tempo and biogeographic history of a mammalian adaptive radiation". BMC Biol. 6: 4–5. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-10. PMC 2276185. PMID 18275614.

- Bininda-Emonds OR, Gittleman JL, Purvis A (1999). "Building large trees by combining phylogenetic information: a complete phylogeny of the extant Carnivora (Mammalia)" (PDF). Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 74 (2): 143–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.328.7194. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00184.x. PMID 10396181.

- ^ "Washington State Periodic Status Review for the Sea Otter" (PDF). Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. (link: WDFW seaotter). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5. OCLC 17396377.

- Nickerson, p. 19

- ^ Silverstein, p. 34

- Campbell, Kristin M.; Santana, Sharlene E. (3 October 2017). "Do differences in skull morphology and bite performance explain dietary specialization in sea otters?" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 98: 1408. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyx091. S2CID 91055290 – via Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, Don E.; Bogan, Michael A.; Brownell, Robert L.; Burdin, A. M.; Maminov, M. K. (13 February 1991). "Geographic Variation in Sea Otters, Enhydra lutris". Journal of Mammalogy. 72 (1): 22–36. doi:10.2307/1381977. JSTOR 1381977 – via University of Nebraska – Lincoln.

- Timm-Davis, Lori L.; DeWitt, Thomas J.; Marshall, Christopher D. (9 December 2015). "Divergent Skull Morphology Supports Two Trophic Specializations in Otters (Lutrinae)". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): 7. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043236T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143236. PMC 4674116. PMID 26649575.

- The Wildlife Year. The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. (1991). ISBN 0-276-42012-8

- ^ "Sea Otters, Enhydra lutris". MarineBio.org. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. p. 1342. ISBN 978-90-04-08876-4.

- ^ Nickerson, p. 21

- Silverstein, p. 14

- ^ Yeates, Laura (2007). "Diving and foraging energetics of the smallest marine mammal, the sea otter (Enhydra lutris)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (Pt 11): 1960–1970. doi:10.1242/jeb.02767. PMID 17515421. S2CID 21944946.

- Kenyon, pp. 37–39

- Love, p. 21 and 28

- ^ Love, p. 27

- ^ Silverstein, p. 13

- ^ Love, p. 21

- ^ Kenyon, p. 70

- Silverstein, p. 11

- Hayashi, S.; Houssaye, A.; Nakajima, Y.; Chiba, K.; Ando, T.; Sawamura, H.; Inuzuka, N.; Kaneko, N.; Osaki, T. (2013). "Bone Inner Structure Suggests Increasing Aquatic Adaptations in Desmostylia (Mammalia, Afrotheria)". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e59146. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859146H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059146. PMC 3615000. PMID 23565143.

- Yuan, Yuan; Zhang, Yaolei; Zhang, Peijun; Liu, Chang; Wang, Jiahao; Gao, Haiyu; Hoelzel, A. Rus; Seim, Inge; Lv, Meiqi; Lin, Mingli; Dong, Lijun; Gao, Haoyang; Yang, Zixin; Caruso, Francesco; Lin, Wenzhi (14 September 2021). "Comparative genomics provides insights into the aquatic adaptations of mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (37): e2106080118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11806080Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.2106080118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8449357. PMID 34503999.

- Liwanag, Heather (December 2012). "Morphological and thermal properties of mammalian insulation: the evolutionary transition to blubber in pinnipeds". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 107 (4): 774–787. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.01992.x.

- ^ Mostman Liwanag, Heather Elizabeth (2008). Fur versus Blubber: A comparative look at marine mammal insulation and its metabolic and behavioral consequences (PhD dissertation). University of California, Santa Cruz. ISBN 978-0-549-93125-6. ProQuest 304663143.

- Koopman, Heather N. (7 March 2018). "Function and evolution of specialized endogenous lipids in toothed whales". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 221 (Pt Suppl 1): jeb161471. doi:10.1242/jeb.161471. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 29514890. S2CID 3789040.

- Kenyon, p. 62

- Love, p. 22

- VanBlaricom, p. 64

- "USFWS Species Profile: Southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis)". Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- VanBlaricom, p. 11 and 21

- Kenyon, p. 55

- Love, p. 23

- Kenyon, p. 56

- Kenyon, p. 43

- Love, p. 74

- Kenyon, p. 47

- Winer, J.N.; Liong, S.M.; Verstraete, F.J.M. (2013). "The Dental Pathology of Southern Sea Otters (Enhydra lutris nereis)". Journal of Comparative Pathology. 149 (2–3): 346–355. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2012.11.243. PMID 23348015.

- VanBlaricom, p. 17

- ^ "Sea Otter" (PDF). British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. October 1993. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Love, p.24

- Ortiz RM (June 2001). "Osmoregulation in marine mammals". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (11): 1831–44. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.11.1831. PMID 11441026.

- ^ Love, pp. 69–70

- Love, pp. 70–71

- Kenyon, p. 76

- ^ Reitherman, Bruce (1993). Waddlers and Paddlers: A Sea Otter Story–Warm Hearts & Cold Water (Documentary). U.S.A.: PBS.

- ^ Haley, D., ed. (1986). "Sea Otter". Marine Mammals of Eastern North Pacific and Arctic Waters (2nd ed.). Seattle, Washington: Pacific Search Press. ISBN 978-0-931397-14-1. OCLC 13760343.

- ^ VanBlaricom, p. 22

- "Sea otter". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ^ "Sea otter AquaFact file". Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- ^ Okerlund, Lana (4 October 2007). "Too Many Sea Otters?". Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ Love, p. 49

- VanBlaricom, p. 45

- ^ VanBlaricom, pp. 42–45

- Love, p. 50

- ^ Kenyon, p. 77

- Kenyon, pp. 78–79

- ^ Silverstein, p. 61

- At least one female is known to have died from an infected nose. (Love, p. 52)

- ^ Love, p. 54

- Silverstein, p. 30

- ^ Nowak, Roland M. (1991). Walker's Mammals of the World Volume II (Fifth ed.). Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1141–1143. ISBN 978-0-8018-3970-2.

- Kenyon, p.44

- Love, pp. 56–61

- ^ Love, p. 58

- Silverstein, pp. 31–32

- Love, p. 61

- ^ Love, p. 63

- Love, p. 62

- Love, p. 59

- Kenyon, p. 89

- Silverstein, p. 31

- Silverstein, p. 28

- Love, p. 53

- VanBlaricom, p. 71

- VanBlaricom, pp. 40–41

- VanBlaricom, p. 41

- Silverstein, p. 17

- Nickerson, p. 49

- Silverstein, p. 19

- VanBlaricom, p. 14

- Kenyon, p. 133

- Love, pp. 67–69

- ^ Ogden, Adele (1975). The California sea otter trade, 1784–1848. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-520-02806-7.

- VanBlaricom, p. 54

- ^ Kornev S.I., Korneva S.M. (2004) Population dynamics and present status of sea otters (Enhydra lutris) of the Kuril Islands and southern Kamchatka. Marine Mammals of the Holarctic, Proceedings of 2004 conference. pp. 273–278.

- ^ "Sea Otters – Southwest Alaska Sea Otter Recovery Team (SWAKSORT)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Alaska. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Barrett-Lennard, Lance (20 October 2004). "British Columbia: Sea Otter Research Expedition". Vancouver Aquarium. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (15 June 2007). "California otters rebound, but remain at risk". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2007.

- "Observations, iNaturalist". iNaturalist. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ VanBlaricom, p. 62

- ^ "Trends in the Abundance and Distribution of Sea Otters (Enhydra lutris) in British Columbia Updated with 2013 Survey Results" (PDF). Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada. July 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "Sea Otter Recovery on Vancouver Island's West Coast". Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre Public Education Programme. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Sea Otter, Species at Risk Public Registry

- Sea Otters, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Nickerson, p. 46

- ^ Schrope M (February 2007). "Food chains: killer in the kelp". Nature. 445 (7129): 703–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..703S. doi:10.1038/445703a. PMID 17301765. S2CID 4421362.

- Jameson, Ronald James (1975). An Evaluation of Attempts to Reestablish the Sea Otter in Oregon (PDF) (MSc). Oregon State University. hdl:1957/6719. OCLC 9653603. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- Quinn, Beth (17 October 2004). "Sea otter's stay raises scientists' hopes" (PDF). The Oregonian. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Rare sea otter confirmed at Depoe Bay". The Oregonian. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Silverstein, p. 41

- "Spring 2007 Mainland California Sea Otter Survey Results". U.S. Geological Survey. 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- Rogers, Paul (11 December 2020). "Are sea otters taking a bite out of California's Dungeness crab season?". The Mercury News. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Southern Sea Otters Archived 30 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. nrdc.org

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe; Bates, Alfred; Petroff, Ivan; Nemos, William (1887). History of Alaska: 1730–1885. San Francisco, California: A. L. Bancroft & Company. p. 482. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Stewart, Suzanne; Praetzellis, Adrian (November 2003). Archeological Research Issues for the Point Reyes National Seashore – Golden Gate National Recreation Area (PDF) (Report). Anthropological Studies Center, Sonoma State University. p. 335. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Charles L. Camp; George C. Yount (1 April 1923). "The Chronicles of George C. Yount: California Pioneer of 1826" (PDF). California Historical Society Quarterly. 2 (1): 3–66. doi:10.2307/25177691. JSTOR 25177691. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Battersby, Bob; Maginis, Preston; Nielsen, Susan; Scales, Gary; Torney, Richard; Wynne, Ed (May 2008). Ross, California – The people, the places, the history. Ross Historical Society. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ University of California – Santa Cruz (18 January 2008). "Sea Otter Show Striking Variability in Diets And Feeding Strategies". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- mcLeish, p. 32

- ^ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Proposes that Southern Sea Otter Translocation Program be Terminated" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 5 October 2005. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- "Service Proposes to End Southern Sea Otter Translocation Program". USFWS Pacific Southwest Region. 17 August 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Hatfield, B.B.; Tinker, M.T. (19 September 2016). Annual California Sea Otter Census – 2016 Spring Census Summary. USGS Western Ecological Research Center (Report). doi:10.5066/F7FJ2DWJ.

- "Rare sighting of sea otter off Laguna Beach". KABC-TV/DT. 7 December 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "Balance sought in sea otter conflict". CNN. 24 March 1999. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- Weiss, Kenneth R. (20 December 2012). "U.S. will let otters roam along Southern California coastline". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- mcLeish, p. 264

- ^ "California's Sea Otter Numbers Continue Slow Climb". USGS. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Young Landis, Ben; Tinker, Tim; Hatfield, Brian (3 August 2010). "California Sea Otter Numbers Drop Again". U. S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "Spring 2010 Mainland California Sea Otter Survey Results". USGS Western Ecological Research Center. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Weiss, Kenneth R. (23 September 2010). "Another deadly challenge for the sea otter". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Miller MA; Kudela RM; Mekebri A; Crane D; Oates SC; et al. (2010). Thompson, Ross (ed.). "Evidence for a Novel Marine Harmful Algal Bloom: Cyanotoxin (Microcystin) Transfer from Land to Sea Otters". PLOS ONE. 5 (9): e12576. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512576M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012576. PMC 2936937. PMID 20844747.

- Colliver, Victoria (23 January 2011). "Sea otter deaths jump in 2010". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- USGS (April 2012). "Number of dead California sea otters a record high in 2011". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 64 (4): 671–674. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.03.002.

- Hatfield, Brian; Tinker, Tim (22 September 2014). Spring 2014 California Sea Otter Census Results (Report). Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Southern Sea Otter". USFWS, Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Tinker, M. T.; Hatfield, B. B. (29 September 2017). "California sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) census results, Spring 2017". California sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) census results, spring 2017 (Report). Data Series. U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 1067. p. 9. doi:10.3133/ds1067.

- Gallo-Reynoso JP, Rateibun GB (1997). "Status of Sea Otters (Enhydra Lutris) in Mexico". Marine Mammal Science. 13 (2): 332–340. Bibcode:1997MMamS..13..332G. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00639.x.

- Schramm Y, Heckel G, Sáenz-Arroyo A, López-Reyes E, Baez-Flores A, Gómez-Hernández G, Lazode-la-Vega-Trinker A, Lubinsky-Jinich D, de los Angeles Milanés-Salinas M (2014). "New evidence for the existence of southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) in Baja California, Mexico". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (3): 1264–1271. Bibcode:2014MMamS..30.1264S. doi:10.1111/mms.12104.

- Williams, Terrie (1989). "Swimming by sea otters: adaptations for low energetic cost locomotion". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 164 (6): 815–824. doi:10.1007/BF00616753. PMID 2724187. S2CID 1926452.

- Wright, Traver; Sheffield-Moore, Melinda; Davis, Randall (2 December 2021). "Sea otters demonstrate that there is more to muscle than just movement – it can also bring the heat". The Conversation. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ VanBlaricom pp. 18–29

- Williams, Perry J.; Hooten, Mevin B.; Esslinger, George G.; et al. (29 November 2018). "The rise of an apex predator following deglaciation". Biodiversity Research. 25 (6): 895–908. doi:10.1111/ddi.12908.