| Siege of Suiyang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the An Lushan rebellion | |||||||

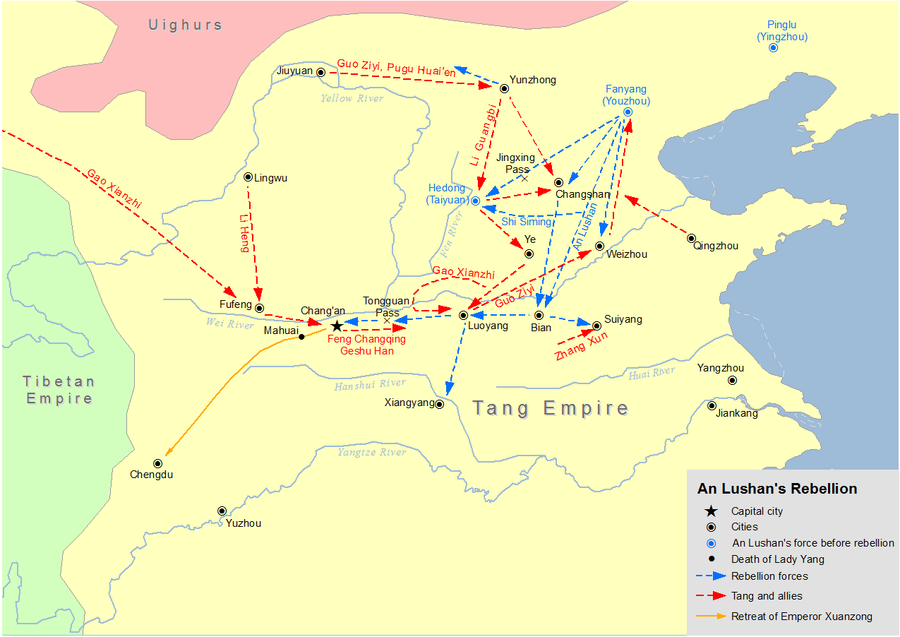

Suiyang during the An Lushan rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Yan | Tang | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

150,000+

|

9,800

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 120,000 dead |

| ||||||

| Up to 50,000 civilians eaten | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 睢陽之戰 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 睢阳之战 | ||||||

| |||||||

The siege of Suiyang was a military campaign during the An Lushan rebellion, launched by the rebel Yan army to capture the city of Suiyang from forces loyal to the Tang dynasty. Although the battle was ultimately won by the Yan army, it suffered major attrition of manpower and time. The siege was noted for the Tang army's determination to fight to the last man, as well as the large-scale cannibalism practised by the defenders, who in this way were able to hold out longer.

Background

The An Lushan rebellion began in December 755. By the end of 756, the rebel Yan army had captured most of northern China, which then included both Tang capitals, Chang'an and Luoyang, and was home to the majority of the empire's population. The Yangtze basin had thus become the main base of the Tang dynasty's war efforts. In January 757, the newly self-proclaimed Yan emperor An Qingxu ordered general Yin Ziqi [zh] (尹子奇) to join forces with general Yang Chaozong (楊朝宗) and besiege Suiyang (present-day Shangqiu, Henan). Suiyang was a city on the Tang-era course of the Grand Canal, sitting midway between the major cities Kaifeng and Xuzhou. The city, therefore, formed a major obstacle for the rebels on the route from the capitals to the southeastern coast, the breadbasket of the Tang dynasty.

The administrator of Suiyang Prefecture at the time, Xu Yuan [zh] (許遠), requested help from garrisons in neighbouring cities. At the time, Zhang Xun, formerly a county magistrate serving in the Tang government, was the leader of volunteer defenders in Yongqiu. The Tang had granted him the title deputy jiedushi of Henan but could not provide any reinforcement or logistic support. Zhang had held off a rebel siege on his city in the previous year. However, as cities in the area fell one by one, Zhang quickly realized that his position in Yongqiu was becoming untenable. Recognizing the strategic importance of Suiyang, he led 3,000 men to aid its defence, bringing the total number of defenders to 6,800. Once he arrived, Zhang Xun took over the military leadership of Suiyang. Yao Kun [zh] (姚誾), the county magistrate of Chengfu, also arrived to help lead the defence of Suiyang. Meanwhile, Yin Ziqi mustered a huge army (estimated at 130,000 men) and started besieging the city in late January.

Timeline

| This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The united army of Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan, around 6,800 men, prepared to defend Suiyang with their lives. Xu Yuan focused on supplies management and after-battle repairs. Zhang Xun, on the other hand, focused on battle tactics.

Despite daily attacks by the Yan army, the Tang soldiers did not give up. Zhang Xun's troops played the battle drums during the night, acting as if they were going to fight. Consequently, the Yan army was forced to stand on guard at night and suffered from lack of sleep. Eventually, some troops did not bother to put on their armour when they heard these battle drums and kept sleeping. After the Yan army lowered their defences, Zhang Xun sent a dozen generals, including the famed archer Nan Jiyun [zh] (南霽雲) and Lei Wanchun [zh] (雷萬春), to lead 50 cavalry each in an attack on the enemy camp. The ambush was successful, and 5,000 Yan troops were slaughtered.

Zhang Xun had long wanted to give Yan morale a significant blow, and the best way to do this would be to hurt or kill Yan general Yin Ziqi. However, Zhang Xun did not know what Yin Ziqi looked like, nor would he be in a mix of soldiers. Zhang Xun, therefore, turned to psychology. He ordered his troops to shoot weeds, instead of arrows, at a few enemy soldiers. When these soldiers noticed they were being hit by weeds and left unharmed, they were overjoyed. They promptly ran to Yin Ziqi to report that the Tang army had already run out of arrows. Zhang Xun noticed where the soldiers ran and ordered his best archer, Nan Jiyun, to shoot at Yin Ziqi. One such arrow hit Yin Ziqi in his left eye, throwing the Yan army instantly into chaos. The siege ended with the expected significant blow to Yan morale.

After 16 days of siege and ambush, the Yan army had reportedly already lost 20,000 men. Yin Ziqi decided his army was too tired to fight, so he ordered a temporary retreat to regroup. Two months later, Yin Ziqi returned to besiege Suiyang with an additional 20,000 fresh troops. He began the final and ultimately successful siege early in the seventh lunar month of 757, continuing it until the city fell four months later.

Originally, Xu Yuan had prepared for the upcoming battle by storing a year's food inside Suiyang. However, the district governor insisted that he share the ample food supply with other nearby fortresses, and hence, the food supply became much less than what Xu Yuan originally planned. By July, the Tang soldiers had fallen into a severe food shortage. Tang soldiers were given tiny daily rations of rice. If they wanted more food, they would need to settle for whatever animals, insects, and tree roots could be found in their vicinity.

Yin Ziqi noticed the famine plaguing the Tang army and ordered more troops to surround Suiyang. He made many siege attempts with siege ladders, but they were all repelled by the determined Tang troops. With limited success, Yin Ziqi even used hooked-pulled carts to pull down the fortress's towers. The Tang soldiers could destroy the hook of these carts before significant damage was made. But even with the battle's success, Zhang Xun knew that with only around 1,600 soldiers left, and most of them sick or hungry, the battle would soon be a lost cause.

By August, all the insects, animals, and vegetation in the besieged area had been eaten. Zhang Xun ordered 30 of his best soldiers under Nan Jiyun to break through and ask for help from nearby fortresses. Nan Jiyun and 26 others successfully broke through. However, none of the nearby local governors were willing to offer troops and food supplies. Finally, Nan Jiyun asked for help from Helan Jinming [zh] (賀蘭進明), governor of nearby Linhuai. Helan had long been jealous of Zhang Xun's abilities. He also wanted to preserve his forces, so he refused to assist Zhang Xun. Instead, he offered Nan Jiyun a large feast to convince him to join his ranks. Nan is said to have replied:

The reason why I risked my life to come here is because the local civilians and my comrades have had no food to eat for over a month. How can I eat such a large feast when I know what my comrades are facing? Although I failed my mission, I will leave a finger with you, as evidence that I did come here.

Immediately after, Nan Jiyun cut off (or bit off, in some versions) one of his own fingers. Furious at Helan's inaction, he rode away, but not before shooting an arrow at the Buddha statue in a nearby temple and stating, "Once I return from defeating the enemy, I will definitely kill Helan! This arrow shows my resolve."

Nan Jiyun's bravery finally convinced Lian Huan, a local governor, to lend 3,000 soldiers to him. Both of them fought their way through the Yan army back into Suiyang. Fighting through the numerous ranks of the Yan army was damaging, and only about 1,000 soldiers from the outside made it inside the fortress.

The starving Tang soldiers, about 1,600, fell into despair at the lack of outside help. Almost everyone tried to convince Zhang Xun to surrender or find some way to escape southward. Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan discussed this, and Xu Yuan concluded, "If Suiyang falls, Yan will be free to conquer the rest of southern China. And on top of it, most of our soldiers are too tired and hungry to run. The only choice we have left is to defend for as long as possible, and hope that a nearby governor will come and help us." Zhang Xun agreed with him. Zhang Xun told his remaining troops, "The nearby governors might be inelegant, but we cannot be disloyal. Another day that we can hold out is another day for the rest of the Tang to prepare defences. We will fight till the very end."

Cannibalism

When the inhabitants of the besieged city ran out of provisions, they started to eat horses first and then "the aged, children and women". In their biographies of Zhang Xun, the Old and New Book of Tang (finished between 945 and 1060) – the primary official dynastic histories covering the Tang period – estimate that about half of the original population of 60,000 people (including the troops) were eaten. When the city finally fell, "there were only 400 survivors", all of whom were soldiers. No civilians seem to have survived.

According to the Old Book of Tang, Zhang Xun killed his own concubine as food for the hungry soldiers to convince them that such extreme sacrifices were worth it.

Xun fetched his concubine, killed her in front of the army and presented her to the soldiers saying: "Brothers, for the sake of your country you have defended this city with united efforts.... I am not able to cut my own flesh to feed you, but how can I take pity on this woman and just sit by and watch the dangers?" As tears rolled down their faces the soldiers were unable to eat. Xun forcefully ordered them to eat her.

The historical sources also indicate that there were clear hierarchies, especially "of gender and age ... that determined who had to die and who might live": women (such as the concubine) were killed first, afterwards "old men and small boys followed", while men of fighting age were generally spared. The New Book of Tang contains a similar account of the events.

The Zizhi Tongjian, a work in chronicle format published a few decades after the New Book of Tang, is largely in agreement with the Books of Tang, but also reconstructs a more detailed timeline of the siege, according to which food supplies started to run out in July, four months before the fall of the city. At that time, only 1,600 soldiers who started consuming tree bark and tea papers were left. One month later, the number of soldiers was down to 600. Around that time, they received relief from outside, but only 1,000 of the 3,000 newly sent soldiers made it into the city alive. With 200 enemy soldiers, Zhang was persuaded to rejoin the Tang forces; this brought the total back to around 1,800.

The sources do not clearly indicate when the cannibalism began, but the words attributed by several of them to Nan Jiyun when requesting reinforcements suggest that it started in the seventh lunar month (approximately July), four months before the fall of the city. In contrast to the two Books of Tang, the Zizhi Tongjian does not estimate how many were eaten. Considering the relatively low number of soldiers still alive during the last months of the siege, its authors may have considered the earlier claims of 30,000 eaten implausible. All primary sources that made specific estimates, however, put the numbers of eaten in the 10,000s, with the Cefu Yuangui even stating that 40–50,000 civilians were eaten. According to the historian David A. Graff, these numbers are "open to question" because, while there might have been 60,000 people in the city at the start of the siege, any food supplies "would have gone to the combatants on a priority basis", hence many civilians "would presumably already have died of starvation or fallen victim to 'unofficial' cannibalism by the time that the garrison began to eat human flesh".

While cannibalism during sieges and famines was not unusual, this case was nevertheless "noteworthy" not only because of its apparently considerable scale, but also because it was "an organized and systematic logistical operation carried out by the soldiers of the garrison" under Zhang Xun's command, as Graff notes.

Fall of Suiyang

The Tang soldiers fought until fewer than 400 of them were alive, but so weak that they lacked the strength to shoot arrows. On 24 November 757, Suiyang fell to the Yan army. Zhang Xun said before the fall, "We are out of strength, and can no longer defend the fortress. Although we have failed the emperor in life, we hope to keep killing enemies after death."

Zhang Xun, Nan Jiyun, and Xu Yuan were all captured. According to an exchange in the Zizhi Tongjian, Yin Ziqi asked Zhang Xun, "I heard that every time you fight, your eyes are ripped open, and your teeth are cracked. Why?" Zhang Xun answered, "I want to swallow rebel traitors, but I cannot hear them." Yin Ziqi then used a dagger to open Zhang Xun's mouth to examine his teeth, and to his surprise, all but three or four of Zhang Xun's teeth were indeed cracked. Zhang Xun finally said, "I die for my emperor, so I will die in peace."

Unable to convince Zhang Xun to surrender, the Yan army attempted to convince Nan Jiyun to surrender, but he refused to speak. Zhang Xun told him, "Eighth brother Nan! All brave men face death. Do not give in to unrighteousness!" Nan Jiyun replied, "I had intended to accomplish great things (by surrendering and living on), but you know me so well. If you say so, how dare I not die?" He then refused to surrender.

Yin Ziqi admired Zhang Xun's bravery and commanding abilities and tried unsuccessfully to persuade Zhang Xun, Nan Jiyun, and Xu Yuan to join the ranks of the Yan. Fearing further danger from his captives, Yin had all three men executed, along with 33 other loyal elite soldiers, including Lei Wanchun and Yao Kun. By the end of the siege, the Yan army had reportedly lost 120,000 men in more than 400 battles for Suiyang.

Only three days after the city's fall, a Tang army sent as reinforcements appeared, but by then it was too late.

Aftermath

| This section includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Zhang Xun was able to repel many overwhelming Yan attacks despite becoming more outnumbered with each battle. Because of Zhang Xun's determination, resource-laden southern China did not come under threat from the rebels for almost two years. With such a large Yan army held at bay, the Tang army was able to use the resources to gather more troops for combat. This gave the Tang army enough time to regroup and strike back at the Yan army.

Before the Battles of Yongqiu and Suiyang, the Yan army intended to conquer the Tang dynasty. Their total army size across the country was well over 300,000 men, vastly outnumbering what the Tang army could have offered at the time. After these two battles, however, the tide had turned, and the Tang army held the upper hand in terms of both manpower and equipment. Although the Yan army emerged victorious at Yongqiu and Suiyang, it suffered irreparable losses. If the Yan army had conquered Suiyang even one year earlier, the Tang might have ended by 757. The Suiyang campaign marked the turning point of the rebellion.

Evaluation and legacy

After the war, the imperial government and literati increasingly portrayed Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan as icons of loyalty and patriotism. The plan by the Tang court to posthumously award Zhang Xun was initially met with controversy due to the mass cannibalism in the siege. Some court officials condemned Zhang's conduct, maintaining "that it would have been better for him to have evacuated Sui-yang than to have eaten the people entrusted to his care". However, seven young scholars spoke in his defence. Only the arguments of one of them – Li Han, who seems to have been a close friend of Zhang Xun – are still known, since parts of them were incorporated into the New Book of Tang and the Zizhi Tongjian.

Li offered three arguments in defence of Zhang's acts: Firstly, that human flesh had only been eaten as "a desperate expedient, a last resort", when other Tang forces failed to come to the rescue. Secondly, that "his stubborn and prolonged defense had kept the rebels out of the Huai River valley and the Lower Yangtze region", preventing them from making further progress and thus greatly contributing to their ultimate downfall. He therefore stated that even if Zhang had intended "from the very start to engage in cannibalism ..., his military accomplishment was so great that the merit and the fault would still have cancelled each other out". Finally, Li argued that Zhang had been loyal to the government up to the death and that praise for him would "encourage others to behave in the same exemplary fashion".

The arguments in favour of the defenders prevailed and Zhang was added to the list of "loyal martyrs" who were rewarded posthumous offices by the emperor. Due to the decision that their merit in maintaining the Tang victory outweighed any concerns, shrines were constructed in honour of Zhang and Xu, first in Suiyang and later also at the Lingyan Pavilion in Chang'an. There they were venerated alongside the most respected officials and generals in Tang history.

Graff suggests that ultimately Zhang Xun was declared "a loyalist icon not in spite of his cannibalism but because of it". In a perilous situation, where people sometimes had to "choose between their loyalty to the dynasty on the one hand and the safety of themselves and their loved ones on the other, the court and its supporters could not afford to allow any doubt as to which considerations should be primary and which secondary". By demonstrating so clearly that "loyalty to the dynasty" was his utmost concern, his "transgressions ... provided a particularly clear-cut object lesson in the proper prioritization of values".

Tales of the heroism of the defenders were embellished both in the works of famous writers and poets during the Tang–Song period, such as Gao Shi, Han Yu, Liu Zongyuan, Wang Anshi, Sima Guang, Ouyang Xiu and Huang Tingjian, and in official histories like the New Book of Tang. A popular poem by the late Song politician Wen Tianxiang cited the stories of Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan as examples of loyalty and persistence to inspire resistance in the face of the Mongol invasion. The Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties all organized state ceremonies in honour of Zhang and Xu; in some regions, Zhang Xun was even revered and worshipped by believers of the Chinese folk religion. Others like Wang Fuzhi and Yuan Mei, however, harshly criticized the defenders. Wang Fuzhi commented that killing for food should not be accepted even in life-or-death situations.

See also

Notes

- Specific estimates in primary sources range from 20,000 to 50,000 civilians eaten. While these numbers seem to be based on estimates of the city's population at the start of the siege, they are questionable because they may well underestimate the number of people who died of other reasons.

References

- Graff 1995, p. 7.

- ^ Graff 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Chen 2000.

- Chong, Key Ray (1990). Cannibalism in China. Wakefield, NH: Longwood. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-893-41618-8.

- ^ Ouyang et al. 1060, ch. 192.

- ^ Pettersson 1999, p. 142.

- ^ Siefkes 2022, p. 265.

- ^ Sima et al. 1084, ch. 220.

- Wang 2018, pp. 44–45.

- Sima et al. 1084, ch. 219.

- Graff 1995, p. 7 (note 20).

- Graff 1995, p. 7 (note 21).

- Graff 1995, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Sima et al. 1084.

- Graff 1995, p. 9.

- Li Han (李翰) in Dong Gao (董誥), ed. (1819). 全唐文 [All Tang Texts] (in Literary Chinese). vol. 430.

- Graff 1995, pp. 10–11.

- Graff 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Wang & Wang 2017.

- Graff 1995, p. 15.

- Wang 2018, p. 42.

- Yuan, Mei. 小倉山房文集 [Collected Works from the Studio of Mt. Xiaocang] (in Chinese). ch. 20.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Liu, Xu; Zhao, Ying, eds. (945). 舊唐書 [Old Book of Tang] (in Literary Chinese).

- Ouyang, Xiu; Song, Qi, eds. (1060). 新唐書 [New Book of Tang] (in Literary Chinese).

- Sima, Guang, ed. (1084). 資治通鑑 [Zizhi Tongjian] (in Literary Chinese).

Secondary sources

- Chen, Jianlin (2000). 略论张巡领导的雍睢保卫战 [A Brief Discussion on the Defense of Yongsui led by Zhang Xun]. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) (in Chinese) (5): 134–141.

- Graff, David A. (1995). "Meritorious Cannibal: Chang Hsün's Defense of Sui-yang and the Exaltation of Loyalty in an Age of Rebellion". Asia Major. 3rd Series. 8 (1): 1–17. ISSN 0004-4482. JSTOR 41645511.

- Pettersson, Bengt (1999). "Cannibalism in the Dynastic Histories". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 71: 73–189.

- Siefkes, Christian (2022). Edible People: The Historical Consumption of Slaves and Foreigners and the Cannibalistic Trade in Human Flesh. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-80073-613-9.

- Wang, Binbin; Wang, Haipeng (2017). 从张巡事件看国人的价值评价 [The Value Evaluation of Chinese People from the Zhang Xun Incident]. Ludong University Journal (Philosophy and Social Sciences) (in Chinese). 34 (3): 13–17, 38.

- Wang, Xian (2018). Flesh and Stone: Competing Narratives of Female Martyrdom from Late Imperial to Contemporary China (PhD thesis). University of Oregon. hdl:1794/23910.

34°22′59″N 115°37′8″E / 34.38306°N 115.61889°E / 34.38306; 115.61889

Categories: