The silleros, cargueros or silleteros (also called saddle-men) were the porters used to carry people and their belongings through routes impossible by horse carriage. A famous example is the use of silleros by colonial officials to be carried across the Quindio pass in the Colombian Andes.

History

Silleros often carried between 100 and 200 pounds (50 and 90 kg) of weight crossing the Quindio pass, considered the most difficult of the northern Andean passes. Besides their baggage, silleros even carried the travelers, such as colonial officials or explorers, in a wickerwork chair mounted on their backs.

The practice was described by Alexander von Humboldt, who crossed the Quindio in 1801 – he refused to be carried and preferred walking. Humboldt noted that porters were generally mestizo or whites, while others have stated that they were most often Indigenous. The contemporary descriptions often referred to the mode of transportation as a lomo de indio (on Indian back).

Another traveler who described the practice was Captain Charles Cochrane of the British Navy, who criticized the infrastructure of Colombia and, as Humboldt did, refused to mount silleros. He wrote that "I have been told that the Spaniards and the natives mount these chairmen with as much sang froid as if they were getting on the back of mules, and some brutal wretches have not hesitated to spur the flanks of these poor unfortunate men when they fancied they were not going fast enough". Cochrane also noted that the 300 silleros of Ibagué rarely lived past the age of 40 and that a leading cause of death was the bursting of a blood vessel or pulmonary problems.

According to nineteenth-century anecdotes, sometimes, when hired by particularly demanding or demeaning masters, the Indian porters would tire from the heavy burdens put upon them and eventually, would throw their riders into the abyss and escape into the forest.

In his work Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man, anthropologist Michael Taussig describes the practice of using silleros to cross the Andes as part of the colonial tendency to see and treat the indigenous people as subhuman wild creatures.

Today

In parts of Andean Colombia, such as Antioquia, the silletero still exists and is considered an important part of the cultural heritage of the area, although now, they only carry goods, not passengers.

The city of Medellín holds an annual Festival of the Flowers every summer. One of its main events is a parade of silleteros who carry silletas filled with artistically-designed floral arrangements.

Gallery

-

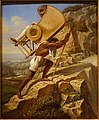

The artist carried in a sillero over the Chiapas from Palenque to Ocosingo, Mexico, by Jean-Frédéric Waldeck, c. 1833

The artist carried in a sillero over the Chiapas from Palenque to Ocosingo, Mexico, by Jean-Frédéric Waldeck, c. 1833

-

Image of travellers being carried across the mountains by silleros, taken from the 1884 work "Viajes por el interior de las provincias de Colombia" by John Potter Hamilton

Image of travellers being carried across the mountains by silleros, taken from the 1884 work "Viajes por el interior de las provincias de Colombia" by John Potter Hamilton

-

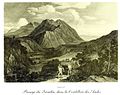

Alexander von Humboldt's depiction of the Quindio pass and the silleros, drawn in 1801

Alexander von Humboldt's depiction of the Quindio pass and the silleros, drawn in 1801

-

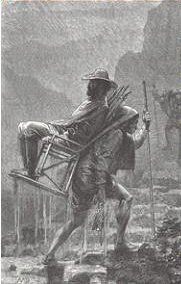

Traveling By Silla, by Frederick Catherwood. Scene in Chiapas. Engraving from 1841 book, "Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan" by John Lloyd Stephens.

Traveling By Silla, by Frederick Catherwood. Scene in Chiapas. Engraving from 1841 book, "Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan" by John Lloyd Stephens.

See also

- Litter (vehicle), a device in which a person is carried by a bearer ("porter" or "chairman")

- Human-powered transport

- Sherpas, people of the Himalayas known for their mountaineering expertise

References

- "La Red Cultural del Banco de la República".

- Acevedo Tarazona, A. 2005. El camino Quindío en el centro occidente de Colombia: la ruta, la retórica del paisaje y los proyectos de poblamiento. Estudios Humanísticos no. 4 pp. 9-36

- Taussig 1986:298

- Alexander von Humboldt David Yudilevich Levy (ed.). 2006. Mi Viaje Por El Camino Del Inca. Editorial Universitaria

- Jason Wilson. 2009. The Andes. p. 223 Oxford University Press

- «...y por caminos y cuestas que suben los hombres abajados y por bejucos y por tales partes que temen ser despeñados suben ellos con cargas y fardos de a tres arrobas y más y algunos en unas silletas de cortezas de árboles llevan a cuestas un hombre o una mujer (...) y si hubiese alguna paga irían con descanso a sus casas, mas todo lo que ganan y les dan a los tristes, lo llevan los encomenderos....» A hombro de indio. (From: Aperçu General sur la Colombie et recits de voyages en Amérique. C.P. Ettienne, Genóve, Imprimerie Maurice Richter 1887. Biblioteca particular de Pilar Moreno de Ángel)at banrepcultural.org

- Taussig 1986:298

- Taussig 1986:298

- C. Taylor, 1825. p. 39-40. The Eclectic Review, Volume 24. Samuel Greatheed, Daniel Parken, Theophilus Williams, Thomas Price, Josiah Conder, William Hendry Stowell, Jonathan Edwards Ryland, Edwin Paxton Hood (eds.)The Eclectic Review vol 24

- Taussig, Michael. 1986. Chapter 18 "On the Indian's Back" in Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. University of Chicago Press.

- Silleteros in Antioquia digital

- John Potter Hamilton at banrepcultural.org

- The Alexander von Humboldt collection at the University of Potsdam