| International Congress on Tuberculosis | |

|---|---|

| Status | defunct |

| Genre | conference |

| Begins | 1899 (1899) |

| Ends | 1912 (1912) |

| Location(s) | Berlin, London, Paris, Washington, Rome |

The International Congress on Tuberculosis was a series of major congresses held between 1899 and 1912 in which scientists and physicians exchanged information on tuberculosis, a significant cause of death at the time.

1899 congress (Berlin)

The first International Congress on Tuberculosis (German: Internationalen Tuberkulosekongress) was held at Berlin on the 24–27 May 1899. The congress was opened by Victor II, Duke of Ratibor in the presence of the Empress of Germany. The congress was held in the Chamber of the Reichstag. Various papers were read on the nature of tuberculosis in man and animals, its diagnosis, pathology, and preventative and curative treatment. Most of the speakers were German. There was no general discussion, but the published proceedings were expected to be valuable.

About 180 delegates represented different governments, universities and other public bodies. About 2,000 members attended the sessions, whose purpose was mainly to instruct doctors, officials and the general public. The speakers explained aspects of the subject and the actions that should be taken to prevent the spread of the disease and to treat it when present.

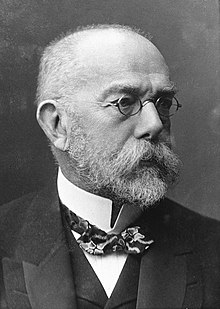

It was known by this time that tuberculosis was caused by a bacillus discovered by Professor Robert Koch of Berlin. Infection was thought to usually be passed by phlegm coughed up by a sick person, dried into dust and then inhaled by a healthy person. It was thought that tuberculosis "is not 'catching', in the popular sense of the word. The disease is not conveyed by the breath, nor even by coughing, except as a rare exception." Milk was known to be an important means of infection, and eating poorly cooked contaminated meat could also cause infection, although rarely.

Means of prevention included free ventilation of houses and wholesome and abundant food. Milk should be boiled, and meat should be carefully inspected, or else the cattle tested for infection. Cures for the disease included abundant food, particularly of a fatty nature, and life in the open air.

1901 congress (London)

The British Congress on Tuberculosis was held in London on 22–27 July 1901. About 2,500 British and foreign delegates were invited, including many eminent pathologists and physicians. The Duke of Cambridge opened the congress on behalf of the king. Great stress was placed on the importance of early treatment, but it was also noted that the patient's dependents must often receive aid. Better sanitary arrangements were also seen as important, and improved housing for the poor. It was agree by all speakers that human sputum was the main vehicle of infection. Professor Brouardel of Paris said, "The danger is in the sputum, which contains thousands of contagious germs. To expectorate on the ground is a disgusting and dangerous habit. Once this habit has quite disappeared, tuberculosis will decrease rapidly."

At this meeting, Robert Koch, who had discovered the tubercle bacillus, announced that it was almost impossible for humans to catch the disease from cattle, and even if they did it would only be a very mild form. He said,

Though the important question whether man is susceptible to bovine tuberculosis at all is not yet absolutely decided, and will not admit of absolute decision to-day or to-morrow, one is nevertheless already at liberty to say that, if such a susceptibility really exists, the infection of human beings is but a very rare occurrence. I should estimate the extent of the infection by the milk and flesh of tuberculous cattle, and the butter made of their milk, as hardly greater than that of hereditary transmission, and I therefore do not deem it advisable to take any measures against it.

John McFadyean of the Royal Veterinary College disputed this view. Frederick Montizambert, Director General of Public Health of the Dominion of Canada, noted that this view was in absolute contradiction of two Royal Commissions whose members included experts such as Sir George Buchanan, Sir John Burdon-Sanderson, Sir Richard Thorne Thorne and Mr. Shirley Murphy. They found that "any person who takes tuberculous matter into the body as food, incurs risk of acquiring tuberculous disease." Montizambert wrote that "the feeling throughout the Congress seemed to be that Dr. Koch's statements were made prematurely, and upon insufficient data, and that, should they prove to be wrong, the amount of harm done may be incalculable." Later Koch modified his views, but the belief that milk with live tubercle bacilli could be drunk without much risk persisted in Britain.

Resolutions adopted at the close of the congress included:

- Tuberculosis sputum is the main agent for the conveyance of the virus of tuberculosis from man to man. Indiscriminate spitting should therefore be suppressed.

- Overcrowding and defective ventilation, damp and insanitary dwellings of the working classes diminish the chances of curing consumption, and are predisposing causes of the disease.

- The provision of sanatoria is an indispensable part of measures for the diminution of tuberculosis.

- Medical officers of health should use all their powers and relax no effort to prevent the spread of tuberculosis by milk and meat.

- A permanent international committee should be appointed to report on the measures for the prevention of tuberculosis in different countries.

1905 congress (Paris)

The International Congress on Tuberculosis (French: Congrès international de la tuberculose) was held in Paris on 2–7 October 1905 in the Grand Palais, which allowed all the attendees to collect in one building. The Grand Palais was suitable for holding the large congress due to its great size and many rooms. The French government made a large contribution to the cost. There were 3,500 delegates in all. They represented foreign governments, universities and special associations and committees, and there were also many doctors, surgeons, veterinarians and local administrators. Émile Loubet, President of the French Republic, welcomed the attendees on the first day, and held a reception at the Élysée Palace after the congress closed. The Municipality of Paris gave a reception at the Hotel de Ville, and Le Figaro staged an “at home” where well known artistes performed. The president of the congress, Dr. Hérard, gave a soiree at the Hotel Continental.

The proceedings of the congress were reported in detail in the Paris papers, including Le Figaro, Le Matin and Le Journal. The congress was divided into four sections, which met separately for about six hours daily: Medical Pathology, Surgical Pathology, Preservation and Assistance of Children, Preservation and Assistance of Adults, Social Hygiene. Forty carefully prepared reports were published in advance, and several hundred special papers were prepared by members of the congress.

A museum on tuberculosis was kept open throughout October, with contributions from France, other European countries and the United States. The exhibition was placed in the partially enclosed rooms and large vestibules leading to staircases on either side of the great hall, and in the galleries. The museum occupied the greater part of the right side of the ground floor, and included a careful arrangement of specimens prepared by leading pathologists and bacteriologists, as well as models and photomicrographs. There were models of the grounds of various sanatoriums, with their woods and walks, hills and meadows, and of the internal facilities. There were maps of the distribution of sanitariums for the rich and for the poor, and photographs of patients in sanitariums, illustrating the life and method of treatment. There were also cases that showed various instruments and products associated with detection and treatment, with sales brochures.

1908 congress (Washington, D.C.)

The 6th Congress was held in the United States in Washington, D.C., from 28 September to 3 October 1908. Hundreds of the attendees came from Canada, Central and South America, Europe and Japan to obtain the latest information about tuberculosis from biological, economic and sociological perspectives. Outside the sessions they were feted at receptions and taken on tours of hospitals, clinics and sanatoriums. A large number of papers were presented. The congress organizers carefully vetted the papers to avoid the sensationalism and reports of "startling discoveries" given at the London and Paris congresses. The main focus was on the influence of housing conditions in the spread of the disease. Some papers:

- Professor Irving Fisher of Yale University talked on Some Economic Aspects of Tuberculosis, which was causing 164 deaths per 100,000 of the population in the United States. 138,000 had died in 1906.

- Iyo Araki presented a report about tuberculosis in Japan.

- Dr. E.C. Schroeder of the Department of Agrigulture, Washington read a paper on Tubercle Bacilli in Cow's Faeces. He found that apparently healthy cows could expel the lethal bacilli in their faeces, and that commercial milk was often contaminated with cow faeces.

- Dr. Alfred F. Hess of New York reported on Tubercle Bacilli in New York Milk. He found tuberculosis in 16% of samples.

- Dr. Aldred Scott Warthin of Michigan discussed Placental Transmission of Tuberculosis, and stated that a mother could easily pass tuberculosis to the fetus. This might be more common than generally thought.

- Dr. Ladislaus Detre of Budapest described his method of producing a differential cutaneous reaction for the diagnosis of tuberculosis.

- Several doctors reported on racial differences in susceptibility to tuberculosis. Dr. M. Fishberg of New York said that the mortality of Jews from tuberculosis was about half that of Christians despite often living in unhealthy slums, perhaps because they had adapted to city life over 2,000 years. Dr. Antonio Stella noted that tuberculosis among Italians was more common in the United States than on Italy. The Irish and the Negroes also had high prevalence, perhaps due to racial factors among the Irish but more to the environment and insanitary habits among the Negroes.

1912 congress (Rome)

The 7th International Congress on Tuberculosis was held in Rome, Italy, on 14–20 April 1912. Robert William Philip of the Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh told the congress,

The tuberculization of the race is a grim chapter in human history. The universal distribution of tuberculosis throughout the civilized world is a fact of immense significance. Tuberculosis has accompanied civilization. Tuberculosis is not essential to civilization. Mankind is responsible for tuberculosis. It is a vicious by-product of an incomplete and ill-informed civilization. If the baneful outcome of misguided civilization has been tubereculization, the role of an enlightened civilization must be detuberculization. What an ignorant civilization has introduced an educated civilization can remove.

Notes

- Separately, International Tuberculosis Conferences organized by the International Anti-Tuberculosis Association were held in Berlin (1902), Copenhagen, Paris (1905), The Hague (1906), Vienna (1907), Philadelphia (1908) and Stockholm (1909). The Ninth International Tuberculosis Conference was held in Brussels, 6–8 October 1910.

Citations

- Pannwitz 1911, p. xvii.

- ^ Maxwell & Pye-Smith 1899, p. 3.

- ^ Maxwell & Pye-Smith 1899, p. 4.

- ^ Maxwell & Pye-Smith 1899, p. 5.

- Maxwell & Pye-Smith 1899, p. 6.

- Maxwell & Pye-Smith 1899, p. 8.

- Montizambert 1901, p. 35.

- ^ Montizambert 1901, p. 36.

- ^ Barnett 2013, p. 69.

- Francis 1959, p. 124.

- Montizambert 1901, p. 37.

- Montizambert 1901, p. 44.

- ^ The International Congress ... Nature, p. 581.

- ^ The International Congress ... Br Med J, p. 901.

- Williams & Bulstrode 1906, p. 3.

- Williams & Bulstrode 1906, p. 4.

- Williams & Bulstrode 1906, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Williams & Bulstrode 1906, p. 5.

- The International Congress ... Br Med J, p. 902.

- ^ The International Congress ... BMJ, p. 1287.

- D'Antonio & Lewenson 2010, p. 20.

- Editorials : The International Congress...

- Iyo Araki San 1908, p. 573.

- The International Congress ... BMJ, p. 1288.

- ^ The International Congress ... BMJ, p. 1290.

- MacVeagh 1913, p. 60.

- ^ Philip 1912, p. 873.

Sources

- Barnett, L. Margaret (15 April 2013), "The People's League of Health and the campaign against bovine tuberculosis in the 1930s", in Jim Phillips, David F. Smith (ed.), Food, Science, Policy and Regulation in the Twentieth Century: International and Comparative Perspectives, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-12860-9, retrieved 12 July 2020

- D'Antonio, Patricia; Lewenson, Sandra (29 September 2010), Nursing Interventions Through Time: History as Evidence, Springer Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8261-0578-3, retrieved 12 July 2020

- "Editorials : The International Congress of Tuberculosis", JAMA, LI (15): 1237, 10 October 1908, doi:10.1001/jama.1908.02540150041007, PMC 5152129, PMID 29003201

- Francis, John (April 1959), "The work of the British Royal Commission on Tuberculosis, 1901–1911", Tubercle, 40 (2): 124–32, doi:10.1016/S0041-3879(59)80153-7, PMID 13647666, retrieved 2020-07-12

- Iyo Araki San (1908), "Tuberculosis in Tokyo and Vicinity", Proceedings of Section V: Hygienic, Social, Industrial and Economic Aspects of Tuberculosis, W. F. Fell

- MacVeagh, Franklin (1913), Annual Report, United States. Public Health Service, retrieved 12 July 2020

- Maxwell, Sir Herbert; Pye-Smith, P. H. (1899), Copy of report of the delegates of Her Majesty's Government at the International Congress on Tuberculosis, held at Berlin on the 24th to the 27th May 1899, Printed for H.M.S.O. by Wyman and Sons, retrieved 2020-07-12

- Montizambert, F. (3 August 1901), "British Congress on Tuberculosis. London, July 22nd to 26th, 1901", Br. Med. J., 2 (2118): 35–44, PMC 2329397

- Pannwitz, Prof. Dr. (1911), IX International Tuberculosis Conference, Berlin-Charlottenburg: International Anti-Tuberculosis Association, retrieved 2020-07-12

- Philip, R.W. (20 April 1912), "An Address on Tuberculization And Detuberculization", Br. Med. J., 1 (2677), International Congress on Tuberculosis at Rome, April, 1912: 873–877, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2677.873, PMC 2344873, PMID 20766122

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "The International Congress on Tuberculosis", Br. Med. J., 2 (2495): 1287–1290, 24 October 1908, PMC 2437870

- "The International Congress on Tuberculosis", Br. Med. J., 2 (2336): 901–902, 7 October 1905, doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2336.901, PMC 2322268

- "The International Congress on Tuberculosis", Nature, 72 (1876): 581–583, 1905, Bibcode:1905Natur..72..581., doi:10.1038/072581d0

- Williams, Charles Theodore; Bulstrode, H. Timbrell (1906), Tuberculosis (International Congress of 1905) (Copy of report of C. Theodore Williams ... and H. Timbrell Bulstrode ... the delegates of His Majesty's Government to the International Congress on Tuberculosis, held at Paris from the 2nd to the 7th October, 1905), retrieved 2020-07-12