The special effects of the 1990 action film Total Recall were developed by visual-effects company Dream Quest Images, with contributions by Stetson Visual Services, Metrolight Studios, and Industrial Light & Magic. Over 100 visual effects (including miniatures and bluescreen effects) were produced for the film, which relied almost entirely on practical effects at a time when computer-generated imagery was a new and rarely-used technique.

Overview

Total Recall's special effects were provided by Dream Quest Images, with Eric Brevig the visual effects supervisor, Alex Funke the special effects photographer, Thomas L. Fisher the special effects supervisor, production designer William Sandell, and effects producer Mary Siceloff. Rob Bottin, who had worked with Verhoeven on RoboCop, provided the character visual effects. Additional effects were by Stetson Visual Services, Metrolight Studios, and Industrial Light & Magic. Senior matte artist Robert Scifo and the Dream Quest team produced forty-eight matte paintings for the film, including all the Martian skies.

The film has over 100 visual effects, including miniatures and bluescreen effects which Verhoeven used because he wanted to move his camera freely around the sets to make them seem more real. Visual-effects plates were in VistaVision for the largest negative possible. Made in the early CGI era, photorealistic or textured imagery was not a suitable option; a spaceship approaching Mars could have been attempted in CGI, but miniatures and motion control photography were easier.

Dream Quest designed a motion-control rig with a precision steel ladder belt encased in plastic. The track was attached to the "Omega driver", a large sprocket attached to the camera dolly. With real-time motion control over forty-eight feet of track and console-controlled camera-orientation options, it could record aspects such as velocity. Information recorded with motion control could be transferred to a separate motion-control rig to replicate the necessary movements and angles for complementary miniature work. When live-action footage was recorded, the miniatures had to be filmed from precise angles and motions to replicate the live-action footage. The crew also had to replicate 40-foot crane shots on a miniature, and encoders were attached to a filming crane to record positions and movements. The encoders were supplemented by cameras set up at specific points to film the crane's motions.

Concept artist Ron Cobb worked on Total Recall from its earliest iterations after completing work on Alien. He conceived of futuristic Los Angeles as a large coastal park with fountains, sunken gardens and solar collectors, describing it as a tranquil place where residents sailed, rode horses, and bicycled. A different version depicted the city after a severe earthquake; the buildings now hung upside-down underground on shock absorbers to mitigate future quakes. At ground level, citizens would enter a one-story slab and take an elevator down to the main buildings. Other features included electromagnetic cars and dirigibles carrying modular housing. Cobb's Mars was a cold, tough and vast desert, with horses and camels wearing pressure suits. He also contributed designs for VTOL aircraft. Illustrator Ron Miller also worked on the Martian landscape. He wanted a plausible city, and created dozens of concepts for domed habitats built into craters and canyons. Miller also conceived transportation (including vehicle types) and a Martian hotel; he wanted the designs to be scientifically plausible and visually interesting.

Although the Martian settings were intended to be realistic, Brevig said that a more cinematic vision was used because "a true depiction of the Martian sky would not have the majesty or mystery that we were working for." People experiencing physical decompression on the Martian surface would actually suffocate instead of experiencing the film's extreme physical distortions.

Creature effects and prosthetics

Bottin had been asked to work on the film while it was being developed by De Laurentiis, but chose to work on the horror film The Thing (1982). When Verhoeven developed Total Recall's creature effects, he wanted to avoid the criticism he had received for the violence and gore of RoboCop. He and Bottin agreed to focus on malformed, stretched flesh instead of blood, but over 3,000 blood packs were still used in the film; many of the more-complex makeup effects were executed in post-production. Bottin and his studio were responsible for the creature effects.

Decompression scenes

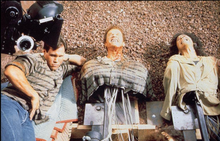

To depict the effects of decompression in the Martian atmosphere, Bottin made molds of Schwarzenegger, Ticotin and Cox by applying latex to their faces as they made exaggerated expressions. The resulting molds were used to create masks to which Bottin added small air pockets which could be filled to further distort their features. About designing the masks, Bottin said: "If the eyes are going to come out and the tongue is going to come out, how does it come out? Does it come out and fall down? Does it come out and move? Does it twist? Does it go up and lick the eyebrows? Does it fall down to the stomach? How does the neck move if the tongue is doing that? What are we going to do with the eyes if the tongue and neck are in the way?"

Four heads were made: one each for Schwarzenegger and Ticotin, and two for Cox. Schwarzenegger and Ticotin's heads were fully articulated, with manually-operated cables controlling swelling tongues, foreheads, cheeks and eyes. The eyes had sculpted muscles and tendons attached to the back, and were lubricated to slide easily out of their sockets. Instead of using air bladders to swell sections of the heads, full-size head- and torso-shaped bladders were constructed and stretched out over a mechanical skeleton; they had smaller air bladders at specific points, which Bottin thought made the bladders appear to be "fighting each other." For one of the Cox heads, rigid veins were laid in the mold and floated on pins to give the finished mask veins beneath the surface where the skin stretched. The other head had a protruding tongue and eyes which emerged fully from the head. The air bladders were inflated by people blowing into pipes, providing a more natural movement than mechanical bellows. Bottin's crew studied video footage of the actors' faces and movements to replicate them, and the heads were enhanced with miniature motors, cables, springs, and rubber muscles. On set, the heads were mounted on mechanical bars which gave the impression of the subject sitting towards the camera. Bottin expected the effect to appear only briefly, and was surprised by how frequently it was used in the film. The hairstyle for Cox's character came from his having to slick his hair back for the molds to be made. Although he had completed two days of filming, he convinced Verhoeven to redo the scenes with the new hairstyle.

Mutants

Bottin called designing the mutants "fun" because he could use any ideas he wanted, but he attempted to retain some realism to avoid identifying the film's events as a dream or reality. An entire civilization of mutants was planned (with each having a different physical deformity), but the idea was unaffordable.

The mother and daughter mutants used prosthetic makeup, but Tony (as a central character) had more detail which could be seen from any camera angle. For the three-breasted prostitute (Lycia Naff), Bottin needed a slender actress to facilitate applying the prosthetic breasts; sizing them took several attempts. Bottin wanted them to look like real flesh affected by gravity. The final appliance extended from Naff's neck to her waist and took two make-up artists up to eight hours to fully apply. The three-breasted prostitute was intended to have four, but audience research indicated that she was reminiscent of a dairy cow and was not sexy. Schwarzenegger had suggested four breasts, with larger ones over smaller ones (based on medical pictures he had seen), but Bottin thought it too realistic and three breasts better suited the film's style.

Benny was intended to have a mechanical extremity, but Johnson said that he suggested giving the character three arms. A half-body cast was built, covering Johnson from his waist to his neck, allowing puppeteers to control the triple-elbowed limb. It was designed with separated bones and open spaces to make it visually impossible for a human arm to be inside and operating it. For the character's death, Johnson wore a bodysuit lined with blood squibs. The scene was filmed with and without blood, in case it was deemed too violent, and the producers chose the bloodless take.

In Bottin's original design of Kuato, he was small and grew out of George's head. Bottin disliked the result and the "monstrous" concept conflicted with his design philosophy, so he made the creature an intelligent baby. Kuato was built into a full-body prosthetic worn by Bell which began under his chin and extended below his waist, with a parachute harness to help support the weight of the cables necessary for fifteen puppeteers to operate Kuato's arms and head. He spent up to nine hours in makeup on his first day of filming in the prosthesis; although the time was shortened with repetition, he found it exhausting. Bell, unable to urinate in the apparatus, asked for a discreet hole to be cut into the foam.

Although some of the Kuato scenes were filmed during principal photography – including his reveal and Schwarzenegger holding his hands – the remainder (including the dialogue scenes) were shot in post-production with an animatronic Bell. Verhoeven was hesitant to use an animatronic because they could use Bell himself, but Bottin believed that removing anything real from the scene would make the overall effect more believable. After seeing test footage, Verhoeven trusted Bottin because he could not distinguish it from the real Bell. However, he wanted a shot of George walking towards Quaid while Kuato is talking; Bottin's crew built a cart which could move the body up and down as it rolled forward, simulating walking.

The mechanical Bell had an articulated head with jaw mechanisms and rolling eyes, and its head could move at a variety of angles. A set of bellows simulated breathing, and Kuato had a separate set so they breathed independently. Both puppets' arms moved with a mechanism operated by one puppeteer. Kuato's eyebrows were computer-controlled, and his eyes were operated with a wireless remote. The George and Kuato puppets, however, required fifteen to twenty operators. To make Kuato speak, servomotors in its mouth were linked to a computer which approximated appropriate shapes for each vowel and consonant. The limited computer system meant that individual pieces of dialogue could not be spliced together; each segment had to be recorded and performed at the same time. Although alternate voice actors were considered, Verhoeven and Bottin believed that Kuato should have a similar vocal timbre and pitch to Bell and chose him for the voice.

Other prosthetics

When Quaid removes the tracker from his skull, Bottin believed that only a mechanical head could make the stunt work. His crew cast Schwarzenegger's head, took measurements and reference photos, and began construction of the mechanical head. When Bottin received the on-set footage, however, the tracker looked like a "silver bullet" which would fit in Schwarzenegger's nose and did not warrant an elaborate special-effects head. After studying the footage, Bottin wanted to have Quaid extract something larger from his nose and commissioned a spherical object housing the small silver tracker. The head was built with a sophisticated jaw and neck mechanism, a tongue that could move and change shape, and could appear to breathe and shake. The scene was filmed at a former glass factory in Saugus. The spherical tracker was channeled through the puppet's nasal passage while a high-powered laser beam a few feet away was aimed at the device to illuminate it. The sphere opens, revealing the smaller silver tracker which was married to the Schwarzenegger footage.

For the climactic elevator battle between Quaid and Richter, Richter's severed arms proved difficult for Bottin's crew. The producers did not want to use a false elevator, and planned to film the scene with a suspended portable elevator. Bottin determined that it was too dangerous for Ironside, and had a cage with handles welded to the elevator's side in which Ironside could stand instead of hanging from the edge. Urethane hands and false arms with metal skeletons and ball sockets in the elbows and shoulders were affixed to sockets attached to Ironside's shoulders. These were controlled by a quick-release valve, triggered by an electric switch on the elevator; when activated, the elbow joints detached. The arms were durable, to withstand Schwarzenegger pulling on them, and the timing was precise to allow Ironside to get down far enough to avoid injury. The wall that severs the arms was eventually replaced with styrofoam in case it actually hit Ironside. As the scene shows Richter falling, separate shoulder-pad mechanisms caused his artificial stumps to flail.

"Fat lady"

When Quaid arrives on Mars, he uses a female disguise (Priscilla Allen, credited as "Fat lady"). In the original script, when Quaid is watching Hauser's video on Earth he learns how to use a device placed over his head which would shoot out steam and open to reveal a mask. Bottin did not like this concept because he thought it was derivative of the Mission: Impossible television series. He conceived a fully-mechanical disguise, but did not know how to realize it. Verhoeven was similarly uncertain, but said that he was convinced by Bottin's enthusiasm and belief that audiences needed to see something original. After about four weeks of Bottin experimenting with the idea, Verhoeven thought that the antagonists would attack Quaid on sight and Bottin conceived of the mask as a bomb.

Finding an actress large enough to believably contain Schwarzenegger's frame was difficult, and wrestlers and bodybuilders were considered before finding Allen. She played the Fat Lady in the opening scenes, appearing to malfunction by contorting her face and slurring her speech. Despite her frame, her head was too small to fit over Schwarzenegger's; the cast of her head was repeatedly sculpted larger, but the mask's features did not line up with Schwarzenegger's. Despite the increased size, the mask was still not large enough for the mechanisms enabling it to split apart on camera.

Four heads were built, but there was still insufficient room for the splitting-effect mechanisms and Bottin accepted the mechanisms being on the outside. The masks were cut into sections with a custom blade to make the separation as fine as possible. After a few days, the plastic began to warp; reconstructed from fibreglass, the cut pieces still warped. Reinforced by steel coated with laminated resin before the head was cut, they continued to warp slightly after several days. A lightweight mask had become a 20-pound (9.1 kg) piece of metal and resin, and it was decided to build a mechanical Schwarzenegger. A body cast of Allen would not fit Schwarzenegger, and was enlarged in proportion to the head. The result was described by Bottin as "ridiculously big", and when Schwarzenegger casts were in it looked like "Beetlejuice after the headhunter shrank his head." With the camera in close enough, however, the difference in scale was less apparent.

Eliminating a live performer created new options. Mechanisms could be concealed on the back of the fat lady's head, making the mask weigh almost 50 pounds (23 kg). Linear-motion bearings were used for the mechanisms, but weighed more than anticipated and brought the final mask weight to 70 pounds (32 kg); the mechanism was so large that the mask could only be shot head-on.

Bottin shot test footage of the effect, showing a hydraulic hose lifting the fat lady's head above its body to reveal Schwarzenegger within. He wanted two shots: one of the head opening, and a second of it closing. The segments did not line up exactly in the test footage, however, and Bottin wanted to do the head-closing shot in reverse to perfect it. On set it worked well, controlled by an operator with a push-pull system for each linear bearing for each slice of the head; children's clay filled in gaps in the starting position. The bearing bent slightly from the weight of the mask when it was open and the back of the Schwarzenegger head had to be cut open to hold the mechanisms, but the mask went back together well for the final effect.

Johnny cab

Designed as a parody of McDonald's, the Johnny cab service is a chain of cheap, futuristic taxis driven by generically polite and cheerful automatons. Bottin and Verhoeven conceived of the name from Jonny Cat cat litter. The automaton was designed to resemble an American 1950s gas-station attendant. Bottin re-used a face mold he had made of Robert Picardo for the science fantasy film Explorers (1985) for the driver, and recommended Picardo for the voice. At his audition, Picardo suggested that the character make a joke about Schwarzenegger's Austrian accent; Verhoeven replied, "We don't do that with Arnold."

Verhoeven wanted the drivers to look imperfect, as if they had been damaged by their passengers over time. Three models were built (one for dialogue scenes which were mainly computer-controlled), including the eyes, mouth, and tongue on a sophisticated neck which moved like a ventriloquist's dummy. The other two were less complex; one was for Schwarzenegger's character to rip out of the taxi, and the other spins uncontrollably with sparks and strobe effects when it explodes. All Johnny Cab scenes were shot on set in Mexico. The models were controlled by cables and computer mechanisms, and the taxi was designed by Cobb.

Visual effects

Holograms

Verhoeven did not want the hologram effects to appear "slick". Different approaches were used for the low-tech versions (such as the tennis instructor) and high-tech versions, such as those used by Quaid to deceive his enemies. For the tennis instructor, the actress was filmed against a bluescreen; the effect was further enhanced by loading the footage into the camera alongside a separate blank film reel and performing a second take to create a raster effect. Footage outside the raster area was double-exposed to make it brighter. When Lori (Sharon Stone) does not match the instructor, it flashes red; a five-frame red filtered exposure was made of a black-and-white version of the footage for this effect. Ripple glass was used to distort the footage when Schwarzenegger walks through it.

So the high-tech holograms appeared smoother, linescreens and ripple glass were only added when they were disturbed. For a subsequent scene where Quaid tests his high-tech holographic watch, Schwarzenegger was filmed with a camera dolly on the left side of the screen using a motion-control track. The footage was then played back in sync with the motion-control move, and Schwarzenegger repeated his movements on the right side of the frame. When the hologram dissolves, Schwarzenegger was filmed against a bluescreen and the animation department used a line pattern and ripple-glass effect to "de-rez" him.

X-ray machine

The train-station X-ray scanner effect was led by Tim McGovern and his team, including George Karl, Rich Cowen and Tom Hutchinson. The scanner, built on location at Churubusco Studios, was a 24-foot (7.3 m)–30-foot (9.1 m) ramp with a 14-foot-long (4.3 m) and 10-foot-tall (3.0 m) piece of black tempered glass in front. Verhoeven did not want to focus on the complex effect, believing that the sequence was more effective if it was shown in an offhand manner.

Stop motion and computer-generated imagery (CGI) were considered for animating the x-ray skeletons, but Brevig and McGovern preferred using motion capture: a then-cutting-edge technology used primarily to analyze golf swings. Six to eight cameras were positioned around the set, and calibration bars focusing the capture system on a specific area were positioned at the X-ray machine's entrance and exit. Schwarzenegger was asked to wear tight black clothing on which white reference balls could be placed to capture his movements, but he arrived in white clothes and refused to change. A motion-capture expert assisting the project deemed the resulting capture footage sufficient, but after several weeks the expert said that the cast's captured movements were unclear. In Schwarzenegger's case, the reference balls were positioned too closely and the software could not discern them individually; the expert could provide only limited cyclical motion as a result. McGovern believed that this was insufficient, since it would be unrealistic for someone with recognizable movements (like Schwarzenegger) to move in a stunted, repetitive way.

In case the capture failed, Brevig had cut holes in the back of the set and used wide-angle lenses to capture the cast's movements from the reverse side. The method switched to CGI after a presentation by Metrolight on their intended approach using keyframe animation with Brevig's footage as a reference; he thought it would be an "exciting" way to realize the effect. This was achieved by blowing up and sharpening the VHS footage, and by transferring it to LaserDisc it gave them discrete frames to work from. McGovern's team conducted a number of tests before deciding on the skeletons' blue-green color. Metrolight digitized a database of skeletons to create the skeletal images, creating an image similar to magnetic resonance imagery, and digitized plastic skeletons molded from human ones. The dog skeleton was created with a timber-wolf skeleton borrowed from the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. After principal photography ended, Metrolight produced some motion capture with the principal actors. For scenes without reference footage, McGovern used his experience in TV-advertising keyframe animation to salvage some of the original motion-capture data.

The finished effect had 11 different shots which were forwarded to Dream Quest to integrate into the live-action footage. Combining the effect with the footage took several passes through the optical printer, but each pass risked degrading the resulting image quality with scratches and airborne detritus. Determined to improve the quality, McGovern and producer George Merkt wanted to restart the process with clean effects shots and footage and offered to fund the process themselves for budgetary reasons. McGovern said that visual effects producer B.J. Rack was touched by their gesture, and approved their request with additional funding.

Two takes were filmed with high-speed cameras as a stuntman, standing in for Quaid, leapt through the X-ray machine glass; explosives shattered the glass just before the stuntman made contact. Metrolight found it difficult to precisely animate his movements leading to the jump.

Sets and vehicles

Sets

Set construction began in January 1989. Total Recall had thirty-five sets spanning eight Estudios Churubusco soundstages. When filming on a set ended, the set was broken down to make room for the next one. The expansive sets were connected by long tunnels continuing beyond the stages, making it possible to drive between them in the futuristic vehicles. Verhoeven, who preferred filming scenes in single (or long) takes, could begin filming on one set and follow the cast through to the next. This setup, however, often involved up to 400 cast and crew members. Cox described the filming as feeling low-budget because of how much of the budget was spent on sets.

The scene of Schwarzenegger and Ticotin entering the reactor was filmed on stages 7 and 8. The reactor bridge, known as "the plank," was mounted on scaffolding at one end and left open on the other; a 20 by 40 feet (6.1 m × 12.2 m) backlit bluescreen was suspended in front. Schwarzenegger and Ticotin were greased and sprayed with sweat, but the additions were incompatible with blue-screen filming and they were toweled off. Actors walked towards the edge, as music played in the background; Verhoeven sometimes played music to heighten the actors' emotions. Fluorescent green lights, for glow, were positioned underneath.

Verhoeven wanted Total Recall to look like it was filmed on location, which required several exterior scenes without exterior locations. A full-scale Martian-landscape set about 15 by 100 by 60 feet (4.6 m × 30.5 m × 18.3 m) was built, that Brevig described as "little more than a patch with this little ridge of red rock." Despite its scale, it could not replicate the vast exteriors Verhoeven wanted; it was re-used for scenes of characters walking on the Martian surface, however, enhanced with matte painting backgrounds and forced perspective miniatures created by Stetson. Blending the effects required extensive experimentation. Funke described how the miniatures' details, such as the size of sand grains or pebbles, and correct contrast and color affected visual realism. Like the main Mars set, the miniatures (such as canyon walls and mountains) were reused and adapted extensively to lower production costs.

Quaid's arrival at the Mars Hilton hotel was filmed with a wide-angle lens and motion-controlled panning. The set had a large window (beyond which was the Martian landscape), and the visual was created with a 40-by-40-foot (12 m × 12 m) bluescreen rig. Making the shot work was difficult, since the bluescreen needed to be lit but far enough from the interior lighting to not reflect it. Since natural light was not coming from the window, the hotel had to be lit from the side; however, the set's shiny floors and accessories reflected the blue light. Since the blue light could not be removed in post-production (because the areas would appear black), the blue reflections were turned red with rotoscoped mattes. Funke described the reflections as "something you don't see but which has to be there to sell the illusion". The bluescreen footage only appears briefly in the scene, because Verhoeven did not want to focus on special effects. The technique was also used for Cohaagen's office. Brevig and Funke found it difficult to match the wide-angle-lens distortion to the miniature landscape footage. The Venusville bar was designed by William Sandell to look hard and metallic, like a Last Chance Saloon "at the end of the universe" with video screens showing pastoral Earth scenes.

For the scene in which Richter and Helm pursue Quaid and Melina to a balcony from the hotel, only the balcony and a small section of the scaffolding Quaid and Melina jump to was built. However, they were filmed in alternate locations: the balcony toward a bluescreen, and Schwarzenegger and Ticotin in front of a bluescreen. The footage was composited with miniatures and matte backgrounds. The pair's stunt doubles jumped off the balcony onto a large airbag in front of a 20-by-40-foot (6.1 by 12.2 m) bluescreen. It had to be lit from behind, so the stunt people would not jump into the lights. The pair then descend a ladder, known as the "ladder of death" because of the motion-control rig used for the camera filming them. Its tracks were mounted almost vertically, and the camera had to be counterweighted with a sand-filled trash can to keep it on the track. The unmanned camera was lowered slowly, while the pan and tilt were operated remotely.

To convey explosive decompression when Richter shoots out the window of the spaceport, the cast were manipulated by wired and concealed support poles; the effect was enhanced with wind machines and debris. Verhoeven was concerned about a later scene in the alien reactor where Schwarzenegger, Cox, and Tictotin are blown to the surface because he could see the wires pulling the trio by hip harnesses in close-ups; for wide shots, removing visible wires would be difficult and costly. To complete the effect, the set was rebuilt vertically. Although the producers called it unaffordable, there was no other way to accomplish the stunt without wires. The camera was positioned on its side, so the trio appeared to be pulled backward when they let go and fell.

One of the final shots, depicting the colonists emerging across the surface of Mars, combined front- and rear-projected elements, matte paintings and other aspects front-projected onto paper: a total of about 17 elements, taking 28 hours to film because of each element's color separation. Most of the Martian residents leaving the colonies appeared in silhouette and were extras from the Dream Quest staff. In the film's final scene, rays of sunlight beaming through the clouds were added by the animation department; they used grain-of-wheat lamps, filming in 100-second exposures with a filter.

Vehicles

The Martian taxis were Volkswagen chassis with two steering wheels, making turning difficult. Three vehicles were built to be driven by stunt drivers, but the driver lacked experience controlling the unconventional vehicles and wrecked them. Johnson accidentally arrived in Churubusco a few weeks before filming began and used the time to learn to drive the vehicles, so he performed the stunts himself. Although the filmmakers were concerned that Schwarzenegger might be injured without a professional, he insisted on riding with Johnson and the stunts were successful.

The Winnebago-sized mole drilling machine was designed by Cobb with conceptual artist Steve Burg. Burg said that when the mole (built on a Toyota or Volkswagen chassis) arrived on set, "nobody was pleased with the way it looked" and the exterior needed to be modified for filming in two days. He developed a concept sketch in fifteen minutes; the mole was essentially a plywood box over the vehicle chassis, and set decorator Bobby Gould had suitcase-sized injection-molded plastic pieces screwed onto the plywood frame. Time limitations forced the designers to focus on the top, right side and rear, which would be visible on camera. Scenic artist George Hanson assisted in three hours with techniques he knew could make pieces appear aged or weathered with paint, including roofing compound, talcum powder and acetone. The shooting schedule was eventually delayed, allowing more time to finesse parts such as the drilling bits.

Vermiculite rocks and Fuller's earth were thrown at the drill by stagehands when it was in motion, but the complex gear system lacked strength and heavier rocks occasionally jammed the drill bits. During the scene in which the mole drills into the wall between Schwarzenegger and Ticotin, the wall was built around the drill so that as it reversed it would then fall, creating the opening the protagonists later use. A heavy piece fell on Ticotin's head; she was stunned but otherwise uninjured, and the footage was used in the film.

Miniatures

The film's miniatures were produced by Stetson in Los Angeles, supervised by Mark Stetson and Robert Spurlock. To create a believable depth of field—the distance between the nearest and the farthest objects in an image—the miniatures were filmed with a long exposure; five seconds of footage could take several hours to shoot. Because of this, miniatures were set up and filmed while principal photography was done in Mexico. When Verhoeven finished filming, he often visited Stetson to advise adjustments to the models.

Mars

The miniature sets were built with forced perspective to create the illusion of an endless landscape, but it was difficult to keep an image in focus and the resulting footage was too sharp; the sharpness made it difficult to realistically blend the miniatures with a matte sky. Funke called it one of his most arduous tasks and compared it to Damnation Alley (1977), which he described as "one of the most disastrous effects films of all time." To solve the problem, scenes were filmed twice: one normally (with an illuminated matte sky against the darkened horizon), and the other with a faint cover of smoke which softened the edge between matte and miniature.

Brevig and his team found it difficult to depict a landscape without an atmosphere because normal methods of disguising flaws in miniatures, such as smoke, could not be used. The landscape had to be visually sharp and have gradation from the foreground to the back to create a realistic scale. Most landscape miniatures were twenty to thirty-five feet deep and trapezoid in shape, with the narrow edge closest to the camera. Some sets could be up to 65 to 70 feet wide, generally about a 1/200 scale. They were built with chicken wire for shape and covered with old carpet before model-maker George Trimmer dressed them in fine sand and red mortar dye. The canyon floor was not intended to be visible but had to be deep, so the model was built 6 feet (1.8 m) above the ground.

Set sections had to be small enough to fit on 8-foot-wide (2.4 m) trucks for transport to Dream Quest. Up to fifteen Martian landscapes were built, most of which were segmented and rearranged for reuse in different settings. The Hilton hotel model was about 20 inches tall, and made of plexiglass and lights. The models had moving parts for realism and to keep the sets from appearing static. The view of the Hilton from Cohaagen's office includes cranes, elevators, and trains, and the reverse angle from the Hilton includes the same elements on the other side. Moving live-action shots, such as those following Cohaagen as he moves around his office in front of the Martian backdrop, had to be matched in the miniature footage. A motion control track used during live filming would record camera movements for replication by cameras filming the miniature.

Quaid's shuttle arriving at the Mars spaceport was one of the first miniature effects filmed. The craft was 3.5 feet (1.1 m) square, with interactive lighting and a quartz engine; its exhaust trail was animated with ripple glass. When it lands, bluescreen workers were added in the foreground to enhance the scale with trains and lights in the surrounding area. Funke planned the subsequent train ride, one of the film's most elaborate shots, based on the end of In the Heat of the Night (1967) in which a closeup of Sidney Poitier on a train pulls back to become an aerial shot. From the inside of the train set, the Martian exterior through the window combined four layers; each moved at a different pace to create the correct speed and depth. Reverse forced perspective was used, moving from smaller objects to the largest, so the mountain miniature set and foreground rocks (apparently in the distance) are closest to the window. A motion-control track around the camera was used to move signage and poles, creating a blur which implied speed.

The exterior of the train was produced in miniature on the Martian sets. Verhoeven wanted to linger on the train before pulling away, and the animation does not begin until the camera pulls back; the apparent single shot combines footage filmed months apart. The train begins on a 1/126 set before the scene switches to a 1/12 scale set of the colony, the change concealed by a foreground matte effect. A 60-foot (18 m) motion-control track was used to capture the scene, helping to manage the switch between elements. As the camera pulls away, Schwarzenegger and other cast members are in the train; two small projectors, built for The Abyss (1989), projected Schwarzenegger and the other passengers from inside the train. Funke knew that the individual techniques would work for the overall effect, but was apprehensive about combining them.

Alien reactor

The alien reactor cavern, conceived as a large ice cave lined with reactor rods, was a combination of miniatures and matte paintings. One of the largest and most complex film sets ever built, it was the film's largest. The Stetson crew spent two months debating whether to build it horizontally or vertically, settling on the latter because it was the only way it could fit on Dream Quest's stage; however, it was limited by the 25-foot (7.6 m) ceilings. The set was built between 1/72 scale and HO scale, measuring about 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, 25 feet (7.6 m) high and 35 to 65 feet (11 to 20 m) deep (different figures are cited), with 8-foot-long (2.4 m) reactor columns. The set's weight often made it sag.

Brevig considered the "mind probe" scene in which Kuato sees Quaid's memories of the reactor among the most difficult to film, and it took three weeks to set up. Appearing as a single take, the scene was filmed with cuts to multiple miniature environments concealed by fast camera movement. It was impossible to use the single miniature because the camera needed to look down and up, and the set had no roof. As the camera moves into an excavation site, the set changes to one with a ceiling and reactor rods. The ice cave was difficult to design because the ice needed to appear shiny; the camera was moving all around the set, and it was difficult to conceal the necessary lighting. Small lights were dotted around instead, to illuminate smaller parts of the ice. Mike Bigelow customized a Mitchell Camera, as small as possible on the end of a tiny pan, tilt, and roll head, to fit in the set; there was less than .25 inches (6.4 mm) clearance between the camera and the columns.

As the camera moves beyond the reactor rods, it passes a bridge on which Cohaagen and Richter are walking. The bridge miniature was 1.375 inches (34.9 mm) wide, and the towers holding the bridge were 6 inches (150 mm) on each side. A larger bridge model was made because they could not film close enough to the miniature to combine it with the live-action footage. Only two full-scale segments were built: a ladder climbed by Quaid and Melina, and a narrow footbridge to which it is connected. The bridge footage of Cohaagen, Richter, and other characters walking into the reactor was filmed in Mexico from the highest point the location crew could find: a water tower on the Churubusco lot. This was rear-projected onto the bridge model. Brevig said that the live-action aspect was essential to convey the scale of the reactor and make the location believable.

Verhoeven wanted the lighting for Quaid and Richter's elevator fight to be "cathedral-like." About three hundred 12-volt brake-light bulbs were wrapped in half-blue color gels and mounted on magnets so they could be positioned anywhere on the miniature set. After Richter's defeat, Schwarzenegger was filmed in a full-scale elevator against a bluescreen. Three scale models were used (the elevator attached to a column, surrounded by other columns, and the tops of the columns), finished with a matte-painted ceiling. A wide shot of the elevator moving towards the reactor activation room was a matte painting with a small image of Schwarzenegger front-projected on a piece of paper with a "flawless" matte surface to keep the brightness of the projected image constant despite changing camera angles. Schwarzenegger leaned back at a 20-degree angle, suspended by a steel cable, to create the correct perspective.

Activating the reactor

The reactor activation involved three miniatures: 1/96, 1/24 (1/32), and 1/8 scale. The initial wide shot of the columns beginning to move downwards re-used segments of the "mind probe" set. The rods were about three-quarters of an inch (19 mm) in diameter.

Making the descending rods was difficult; they needed to appear to be glowing-hot, but were only 3 inches (76 mm) in diameter at 1/24 scale and there was no practical way to light them internally. They were wrapped in retroreflective sheeting, painted with a corrosion texture. Bigelow filmed the scenes and front-projected an orange-red color-gel light through a beam splitter. The projected brightness was gradually increased, making the rods seem to be getting hotter. A mechanism inside the rods allowed them to lower. Because the retroreflective material did not scatter light onto the rest of the miniature, conventional lights were shone on the ice surface at the same time to evoke reflected light. The setup was overseen by Dana Yuricich. The 1/8-scale set contained the largest rods, 12 inches (300 mm) in diameter, used for a close-up of the ice being penetrated and steam being emitted. The rods, made of plexiglass and filled with lights to make them bright, were textured with paint to look red-hot; Tom Valentine designed that shot. About ten puppeteers underneath the set broke the resin and wax ice as the rods penetrated.

As the ice cracks, releasing gas, dozens of crew triggered the effects, fire extinguishers, nitrogen vapor, and steam beneath the set. The nitrogen looked good, but was difficult to control. The effect was quick, and was filmed with high-speed cameras to make it appear slower. It took several takes, with the crew learning from mistakes. It had thirty reactor rod housings, each about 2 feet (0.61 m) square and 9 feet (2.7 m) long, cantilevered and supported by large vertical trusses. Fifty-five gallon drums of water were used as counterweights. When the rods hit the ice, thousand-watt lights shine up through the color gels. This shot was also overseen by Tom Valentine.

Mountain

The Martian mountain eruption was filmed in the 35-foot-tall (11 m) Agricultural Hall No. 5 (a former blimp hangar) at the Ventura County Fair, since it was the only local place large enough to position lighting far enough from the set for the necessary angles and shadows. The mountain, 14 feet (4.3 m) high and 46 feet (14 m) in diameter, was constructed in nine pieces to facilitate transportation. Only the camera-facing part was built in detail, with the rear left open to operate effects from within (including vapor steam and chemical smoke). Behind the model was a chimney, designed to funnel liquid nitrogen and steam in a large plume. Air mortars were used to burst through the paper-thin plaster mountaintop; mountain shaking levers were also used. The top of the mountain was cast in lightweight plaster, textured on the underside with small shapes separated by thin plaster so the cap would disintegrate when hit by the air mortar. The effect took about a week to set up, and another week to film.

Special effects artists Richard Stutsman and Randy Cabral installed copper tubing in the top third of the mountain to direct jets of steam and nitrogen to its surface. Erik Stohl constructed mechanical aspects that made parts of the mountain rise or crumble.

The air mortars were loaded with gravel, which provided more control of blast direction than a basic explosive; Funke also believed that the gravel explosions had a more "visceral" feel. AB smoke was also used: a two-liquid solution which remained inert until it was mixed, when it rapidly generated a large volume of smoke. One of the liquids was spread on parts set to be detonated and the other on other parts of the mountain, so when the explosions occurred the liquids would mix and create smoke. The concoction was difficult to work with and dangerous to breathe, so the Stetson crew created additional protective gear from black polyethylene; face masks and protective garments were needed because of the toxic chemical smoke.

The scene was filmed in two takes, with different frame speeds. Long shots were filmed at 48 frames per second because the vapor was only accurately scaled to the model at this speed; the explosion was filmed close-up at 120 fps. Bob Primes, director of photography for the explosion scene, used four perf for the closeup (since it did not require optical manipulation) and eight perf for the long shot because it had to show an atmosphere forming overhead.

For the atmosphere, Gary Platek shone a high-powered laser to create a sheet of light and passed nitrogen vapor through it. As the atmosphere becomes denser, a cloud tank was used until it transitions to a matte painting. To supplement the full mountain views, insert material (including background plates for Quaid and Melina writhing on the slopes) was filmed on larger-scale partial miniatures at Dream Quest. To replicate the earthquake on the live-action Hilton sets as the mountain erupts, they looked at making the lights shake (among other things) when an actual earthquake began. The crew was evacuated (since the buildings were not reinforced), and they ultimately decided to create the effect with an optical printer. Many shots of windows shattering were filmed with miniatures. Bluescreens behind the windows were used, or black screens if no one moved in front of the shot; black provided greater freedom in lighting the set. Model window grids were built and mounted face down over the camera so the glass would fall when shattered. Some of the shots were composited with scenes of extras reacting and diving out of the way, enhanced with rotoscoped mattes which combined the shattering glass with live action.

References

Citations

- ^ Murray 1990b, p. 32.

- ^ Magid, Ron (March 2, 2020). "Many Hands Make Martian Memories in Total Recall". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Allis, Tim (June 5, 2020). "A Face You Can't Totally Recall? Bad Guy Michael Ironside Chased Arnold Schwarzenegger to Mars". People. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Failes, Ian (June 4, 2015). "Recalling Total Recall". Fxguide. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 7.

- ^ Damore, Meagan (December 7, 2020). "Total Recall Star Marshall Bell Reflects on the Film's Enduring Legacy". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Kaye, Don (December 7, 2020). "How Total Recall Brought a Memorable Villain to Life". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ "Total Recall". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 8.

- Roberts 1990, p. 6.

- Murray 1990b, pp. 31–32.

- Zalben, Alex (December 4, 2020). "'Total Recall' 30th Anniversary: Get an Exclusive Look Behind the Scenes at the Mars That Almost Was". Decider. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Svitil, Torene (June 6, 1990). "Rob Bottin: A Wizard in the World of Special Effects : Movies: The makeup effects artist creates more high-tech illusion in the futuristic action-thriller 'Total Recall.'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 32.

- Murray 1990b, p. 31.

- ^ Pockross, Adam (June 1, 2020). "Total Recall At 30: Cohaagen, Benny & Johnny Cab Recall Paul Verhoeven's Mind-bending Masterpiece". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 19.

- ^ Roberts 1990, pp. 19–20.

- Smith, Adam; Williams, Owen (February 12, 2015). "Triple Dutch: Paul Verhoeven's sci-fi trilogy". Empire. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Vineyard, Jennifer (August 3, 2012). "A Candid Conversation With Total Recall's Original Three-Breasted Woman". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Siegel, Alan (June 4, 2020). "Arnold Schwarzenegger's Mission to Mars". The Ringer. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 20.

- ^ Pockross, Adam (June 25, 2020). "When Mel Johnson Jr. First Read Total Recall's Description Of Benny, He Threw The Script Across The Room". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 22.

- Roberts 1990, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Roberts 1990, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 28.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 13.

- Roberts 1990, pp. 13, 15.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 15.

- Roberts 1990, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 11.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 9.

- Total Recall | How 16 Seconds of CGI Earned an Academy Award

- Broeske, Pat H. (December 4, 1988). "Spaced Out". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- Slater-Williams, Josh (November 24, 2020). "I can remember it for you wholesale: The making of Total Recall, 30 years on". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Murray 1990b, p. 59.

- Murray 1990b, p. 29.

- Murray 1990b, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 16.

- Armstrong, Vic (May 12, 2011). "What was it like being a stunt director on Total Recall?". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- Roberts 1990, p. 33.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 17.

- Roberts 1990, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Roberts 1990, pp. 31–32.

Works cited

- Murray, Will (May 1990). "Postcards From Mars". Starlog. No. 154. United States: Starlog Group, Inc. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Roberts, Paul (August 1990). "Ego Trip". Cinefex. No. 32. United States. ISSN 0198-1056. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

| Total Recall | |

|---|---|

| Based on "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" (1966) by Philip K. Dick | |

| Films |

|

| Television |

|

| Video games |

|

| Related |

|