Syntax highlighting is a feature of text editors that is used for programming, scripting, or markup languages, such as HTML. The feature displays text, especially source code, in different colours and fonts according to the category of terms. This feature facilitates writing in a structured language such as a programming language or a markup language as both structures and syntax errors are visually distinct. This feature is also employed in many programming related contexts (such as programming manuals), either in the form of colorful books or online websites to make understanding code snippets easier for readers. Highlighting does not affect the meaning of the text itself; it is intended only for human readers.

Syntax highlighting is a form of secondary notation, since the highlights are not part of the text meaning, but serve to reinforce it. Some editors also integrate syntax highlighting with other features, such as spell checking or code folding, as aids to editing which are external to the language.

Practical benefits

Syntax highlighting is one strategy to improve the readability and context of the text; especially for code that spans several pages. The reader can easily ignore large sections of comments or code, depending on what they are looking for. Syntax highlighting also helps programmers find errors in their program. For example, most editors highlight string literals in a different color. Consequently, spotting a missing delimiter is much easier because of the contrasting color of the text. Brace matching is another important feature with many popular editors. This makes it simple to see if a brace has been left out or locate the match of the brace the cursor is on by highlighting the pair in a different color.

A study published in the conference PPIG evaluated the effects of syntax highlighting on the comprehension of short programs, finding that the presence of syntax highlighting significantly reduces the time taken for a programmer to internalise the semantics of a program. Additionally, data gathered from an eye-tracker during the study suggested that syntax highlighting enables programmers to pay less attention to standard syntactic components such as keywords.

Support in text editors

Some text editors can also export the coloured markup in a format that is suitable for printing or for importing into word-processing and other kinds of text-formatting software; for instance as a HTML, colorized LaTeX, PostScript or RTF version of its syntax highlighting. There are several syntax highlighting libraries or "engines" that can be used in other applications, but are not complete programs in themselves, for example the Generic Syntax Highlighter (GeSHi) extension for PHP.

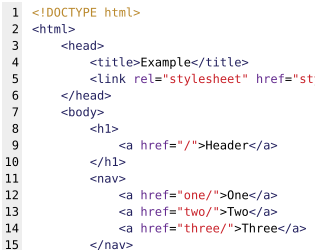

For editors that support more than one language, the user can usually specify the language of the text, such as C, LaTeX, HTML, or the text editor can automatically recognize it based on the file extension or by scanning contents of the file. This automatic language detection presents potential problems. For example, a user may want to edit a document containing:

- more than one language (for example when editing an HTML file that contains embedded JavaScript code),

- a language that is not recognized (for example when editing source code for an obscure or relatively new programming language),

- a language that differs from the file type (for example when editing source code in an extension-less file in an editor that uses file extensions to detect the language).

In these cases, it is not clear what language to use, and a document may not be highlighted or be highlighted incorrectly.

Syntax elements

Most editors with syntax highlighting allow different colors and text styles to be given to dozens of different lexical sub-elements of syntax. These include keywords, comments, control-flow statements, variables, and other elements. Programmers often heavily customize their settings in an attempt to show as much useful information as possible without making the code difficult to read.

Called syntax decoration, some editors also display certain syntactical elements in more visually pleasing ways, for example by replacing a pointer operator like -> in source code by an actual arrow symbol (→), or changing text decoration clues like /italics/, *boldface*, or _underline_ in source code comments by an actual italics, boldface, or underlined presentation.

Examples

Below is a comparison of a snippet of C code:

| Standard rendering | Syntax highlighting |

|---|---|

/* Hello World */

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

|

/* Hello World */

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

|

Below is another snippet of syntax highlighted C++ code:

// Create "window_count" Window objects:

const auto window_count = int{10};

auto windows = std::array<std::shared_ptr<Window>, max_window_count>{};

for (auto i = int{0}; i < window_count; ++i) {

windows = std::make_shared<Window>();

}

In the C++ example, the editor has recognized the keywords const, auto, int, and for. The comment at the beginning is also highlighted in a specific manner to distinguish it from working code.

History and limitations

The ideas of syntax highlighting overlap significantly with those of syntax-directed editors. One of the first such editors for code was Wilfred Hansen's 1969 code editor, Emily. It provided advanced language-independent code completion facilities, and unlike modern editors with syntax highlighting, actually made it impossible to create syntactically incorrect programs.

In 1982, Anita H. Klock and Jan B. Chodak filed a patent for the first known syntax highlighting system, which was used in the Intellivision's Entertainment Computer System (ECS) peripheral, released in 1983. It would highlight different elements of BASIC programs and was implemented in an attempt to make it easier for beginners, especially children, to start writing code. Later, the Live Parsing Editor (LEXX) written for the VM operating system for the computerization of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1985 was one of the first to use color syntax highlighting. Its live parsing capability allowed user-supplied parsers to be added to the editor, for text, programs, data file, etc. On microcomputers, MacPascal 1.0 (October 10, 1985) recognized Pascal syntax as it was typed and used font changes (e.g., bold for keywords) to highlight syntax on the monochrome compact Macintosh and automatically indented code to match its structure.

Some text editors and code formatting tools perform syntax highlighting using pattern matching heuristics (e.g. Regular expressions) rather than implementing a parser for each possible language. This can result in a text rendering system displaying somewhat inaccurate syntax highlighting and in some cases performing slowly. A solution used by text editors to overcome this problem is not always parsing the whole file but rather just the visible area, sometimes scanning backwards in the text up to a limited number of lines for "syncing".

On the other hand, the editor often displays code during its creation, while it is incomplete or incorrect, and the strict parsers (like ones used in compilers) would fail to parse the code most of the time.

Some modern, language-specific IDEs (in contrast to text editors) perform full language parsing which results in very accurate understanding of code. An extension of syntax highlighting was called "semantic highlighting" in 2009 by David Nolden for the open-source C++ IDE KDevelop. For example, semantic highlighting may give local variables unique distinct colors to improve the comprehensibility of code. In 2014 the idea of colored local variables was further popularized due to a blog post by Evan Brooks, and after that, the idea was transferred to other popular IDEs like Visual Studio, Xcode, and others.

Color in a user interface is less useful if the user has some degree of color blindness.

See also

- Programming features in a Comparison of text editors

- Indent style

- Secondary notation

- Structure editor

- Parsing

- Solarized (color scheme)

References

- Jim D'Anjou; Sherry Shavor; Scott Fairbrother; Dan Kehn; John Kellerman; Pat McCarthy (2005). The Java developer's guide to Eclipse (2nd ed.). Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-30502-2.

- Sarkar, Advait (2015). "The impact of syntax colouring on program comprehension". Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Psychology of Programming Interest Group: 49–58. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- Hansen, Wilfred J. (1971). "User engineering principles for interactive systems". Proceedings of the Fall Joint Computer Conference FJCC 39. AFIPS. pp. 5623–532.

- Hansen, Wilfred. "Emily - An Editor for Structured Text". Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Syntax error correction method and apparatus, 1982-10-29, retrieved 2018-04-12

- Mattel Intellivision: Intellivision Computer Module Owner's Guide (1983)(Mattel)(US). 1983.

- "Intellivision Classic Video Game System / Entertainment Computer System". www.intellivisionlives.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-17. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- Cowlishaw, M. F. (1987). "LEXX – A programmable structured editor" (PDF). IBM Journal of Research and Development, Vol 31, No. 1, IBM Reprint order number G322-0151. IBM.

- Allen, Dan (2011-10-10). "A Trio of Historical Recollections". mpw-dev (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "KEDIT Language Definition Files". Kedit. Mansfield Software Group, Inc. 2012. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- "2009 blog post on Semantic Highlighting introduced in KDevelop by David Nolden". 8 January 2009.

- "2014 blog post on Semantic Highlighting by Evan Brooks". 17 April 2017.

- "Visual Studio Magazine article on semantic highlighting".

- "Github page of a plugin which implements semantic highlighting for Xcode". GitHub. 14 September 2022.