| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In mathematics, an inequality is a relation which makes a non-equal comparison between two numbers or other mathematical expressions. It is used most often to compare two numbers on the number line by their size. The main types of inequality are less than (<) and greater than (>).

Notation

There are several different notations used to represent different kinds of inequalities:

- The notation a < b means that a is less than b.

- The notation a > b means that a is greater than b.

In either case, a is not equal to b. These relations are known as strict inequalities, meaning that a is strictly less than or strictly greater than b. Equality is excluded.

In contrast to strict inequalities, there are two types of inequality relations that are not strict:

- The notation a ≤ b or a ⩽ b or a ≦ b means that a is less than or equal to b (or, equivalently, at most b, or not greater than b).

- The notation a ≥ b or a ⩾ b or a ≧ b means that a is greater than or equal to b (or, equivalently, at least b, or not less than b).

In the 17th and 18th centuries, personal notations or typewriting signs were used to signal inequalities. For example, In 1670, John Wallis used a single horizontal bar above rather than below the < and >. Later in 1734, ≦ and ≧, known as "less than (greater-than) over equal to" or "less than (greater than) or equal to with double horizontal bars", first appeared in Pierre Bouguer's work . After that, mathematicians simplified Bouguer's symbol to "less than (greater than) or equal to with one horizontal bar" (≤), or "less than (greater than) or slanted equal to" (⩽).

The relation not greater than can also be represented by the symbol for "greater than" bisected by a slash, "not". The same is true for not less than,

The notation a ≠ b means that a is not equal to b; this inequation sometimes is considered a form of strict inequality. It does not say that one is greater than the other; it does not even require a and b to be member of an ordered set.

In engineering sciences, less formal use of the notation is to state that one quantity is "much greater" than another, normally by several orders of magnitude.

- The notation a ≪ b means that a is much less than b.

- The notation a ≫ b means that a is much greater than b.

This implies that the lesser value can be neglected with little effect on the accuracy of an approximation (such as the case of ultrarelativistic limit in physics).

In all of the cases above, any two symbols mirroring each other are symmetrical; a < b and b > a are equivalent, etc.

Properties on the number line

Inequalities are governed by the following properties. All of these properties also hold if all of the non-strict inequalities (≤ and ≥) are replaced by their corresponding strict inequalities (< and >) and — in the case of applying a function — monotonic functions are limited to strictly monotonic functions.

Converse

The relations ≤ and ≥ are each other's converse, meaning that for any real numbers a and b:

a ≤ b and b ≥ a are equivalent.Transitivity

The transitive property of inequality states that for any real numbers a, b, c:

If a ≤ b and b ≤ c, then a ≤ c.If either of the premises is a strict inequality, then the conclusion is a strict inequality:

If a ≤ b and b < c, then a < c. If a < b and b ≤ c, then a < c.Addition and subtraction

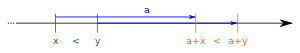

A common constant c may be added to or subtracted from both sides of an inequality. So, for any real numbers a, b, c:

If a ≤ b, then a + c ≤ b + c and a − c ≤ b − c.In other words, the inequality relation is preserved under addition (or subtraction) and the real numbers are an ordered group under addition.

Multiplication and division

The properties that deal with multiplication and division state that for any real numbers, a, b and non-zero c:

If a ≤ b and c > 0, then ac ≤ bc and a/c ≤ b/c. If a ≤ b and c < 0, then ac ≥ bc and a/c ≥ b/c.In other words, the inequality relation is preserved under multiplication and division with positive constant, but is reversed when a negative constant is involved. More generally, this applies for an ordered field. For more information, see § Ordered fields.

Additive inverse

The property for the additive inverse states that for any real numbers a and b:

If a ≤ b, then −a ≥ −b.Multiplicative inverse

If both numbers are positive, then the inequality relation between the multiplicative inverses is opposite of that between the original numbers. More specifically, for any non-zero real numbers a and b that are both positive (or both negative):

If a ≤ b, then 1/a ≥ 1/b.All of the cases for the signs of a and b can also be written in chained notation, as follows:

If 0 < a ≤ b, then 1/a ≥ 1/b > 0. If a ≤ b < 0, then 0 > 1/a ≥ 1/b. If a < 0 < b, then 1/a < 0 < 1/b.Applying a function to both sides

Any monotonically increasing function, by its definition, may be applied to both sides of an inequality without breaking the inequality relation (provided that both expressions are in the domain of that function). However, applying a monotonically decreasing function to both sides of an inequality means the inequality relation would be reversed. The rules for the additive inverse, and the multiplicative inverse for positive numbers, are both examples of applying a monotonically decreasing function.

If the inequality is strict (a < b, a > b) and the function is strictly monotonic, then the inequality remains strict. If only one of these conditions is strict, then the resultant inequality is non-strict. In fact, the rules for additive and multiplicative inverses are both examples of applying a strictly monotonically decreasing function.

A few examples of this rule are:

- Raising both sides of an inequality to a power n > 0 (equiv., −n < 0), when a and b are positive real numbers: 0 ≤ a ≤ b ⇔ 0 ≤ a ≤ b. 0 ≤ a ≤ b ⇔ a ≥ b ≥ 0.

- Taking the natural logarithm on both sides of an inequality, when a and b are positive real numbers: 0 < a ≤ b ⇔ ln(a) ≤ ln(b). 0 < a < b ⇔ ln(a) < ln(b). (this is true because the natural logarithm is a strictly increasing function.)

Formal definitions and generalizations

A (non-strict) partial order is a binary relation ≤ over a set P which is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive. That is, for all a, b, and c in P, it must satisfy the three following clauses:

- a ≤ a (reflexivity)

- if a ≤ b and b ≤ a, then a = b (antisymmetry)

- if a ≤ b and b ≤ c, then a ≤ c (transitivity)

A set with a partial order is called a partially ordered set. Those are the very basic axioms that every kind of order has to satisfy.

A strict partial order is a relation < that satisfies:

- a <⃥͏ a (irreflexivity)

- if a < b, then b <⃥͏ a (asymmetry)

- if a < b and b < c, then a < c (transitivity)

Some types of partial orders are specified by adding further axioms, such as:

- Total order: For every a and b in P, a ≤ b or b ≤ a .

- Dense order: For all a and b in P for which a < b, there is a c in P such that a < c < b.

- Least-upper-bound property: Every non-empty subset of P with an upper bound has a least upper bound (supremum) in P.

Ordered fields

Main article: Ordered fieldIf (F, +, ×) is a field and ≤ is a total order on F, then (F, +, ×, ≤) is called an ordered field if and only if:

- a ≤ b implies a + c ≤ b + c;

- 0 ≤ a and 0 ≤ b implies 0 ≤ a × b.

Both and are ordered fields, but ≤ cannot be defined in order to make an ordered field, because −1 is the square of i and would therefore be positive.

Besides being an ordered field, R also has the Least-upper-bound property. In fact, R can be defined as the only ordered field with that quality.

Chained notation

The notation a < b < c stands for "a < b and b < c", from which, by the transitivity property above, it also follows that a < c. By the above laws, one can add or subtract the same number to all three terms, or multiply or divide all three terms by same nonzero number and reverse all inequalities if that number is negative. Hence, for example, a < b + e < c is equivalent to a − e < b < c − e.

This notation can be generalized to any number of terms: for instance, a1 ≤ a2 ≤ ... ≤ an means that ai ≤ ai+1 for i = 1, 2, ..., n − 1. By transitivity, this condition is equivalent to ai ≤ aj for any 1 ≤ i ≤ j ≤ n.

When solving inequalities using chained notation, it is possible and sometimes necessary to evaluate the terms independently. For instance, to solve the inequality 4x < 2x + 1 ≤ 3x + 2, it is not possible to isolate x in any one part of the inequality through addition or subtraction. Instead, the inequalities must be solved independently, yielding x < 1/2 and x ≥ −1 respectively, which can be combined into the final solution −1 ≤ x < 1/2.

Occasionally, chained notation is used with inequalities in different directions, in which case the meaning is the logical conjunction of the inequalities between adjacent terms. For example, the defining condition of a zigzag poset is written as a1 < a2 > a3 < a4 > a5 < a6 > ... . Mixed chained notation is used more often with compatible relations, like <, =, ≤. For instance, a < b = c ≤ d means that a < b, b = c, and c ≤ d. This notation exists in a few programming languages such as Python. In contrast, in programming languages that provide an ordering on the type of comparison results, such as C, even homogeneous chains may have a completely different meaning.

Sharp inequalities

An inequality is said to be sharp if it cannot be relaxed and still be valid in general. Formally, a universally quantified inequality φ is called sharp if, for every valid universally quantified inequality ψ, if ψ ⇒ φ holds, then ψ ⇔ φ also holds. For instance, the inequality ∀a ∈ R. a ≥ 0 is sharp, whereas the inequality ∀a ∈ R. a ≥ −1 is not sharp.

Inequalities between means

See also: Inequality of arithmetic and geometric meansThere are many inequalities between means. For example, for any positive numbers a1, a2, ..., an we have

where they represent the following means of the sequence:

Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

See also: Cauchy–Schwarz inequalityThe Cauchy–Schwarz inequality states that for all vectors u and v of an inner product space it is true that where is the inner product. Examples of inner products include the real and complex dot product; In Euclidean space R with the standard inner product, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is

Power inequalities

A power inequality is an inequality containing terms of the form a, where a and b are real positive numbers or variable expressions. They often appear in mathematical olympiads exercises.

Examples:

- For any real x,

- If x > 0 and p > 0, then In the limit of p → 0, the upper and lower bounds converge to ln(x).

- If x > 0, then

- If x > 0, then

- If x, y, z > 0, then

- For any real distinct numbers a and b,

- If x, y > 0 and 0 < p < 1, then

- If x, y, z > 0, then

- If a, b > 0, then

- If a, b > 0, then

- If a, b, c > 0, then

- If a, b > 0, then

Well-known inequalities

See also: List of inequalitiesMathematicians often use inequalities to bound quantities for which exact formulas cannot be computed easily. Some inequalities are used so often that they have names:

- Azuma's inequality

- Bernoulli's inequality

- Bell's inequality

- Boole's inequality

- Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

- Chebyshev's inequality

- Chernoff's inequality

- Cramér–Rao inequality

- Hoeffding's inequality

- Hölder's inequality

- Inequality of arithmetic and geometric means

- Jensen's inequality

- Kolmogorov's inequality

- Markov's inequality

- Minkowski inequality

- Nesbitt's inequality

- Pedoe's inequality

- Poincaré inequality

- Samuelson's inequality

- Sobolev inequality

- Triangle inequality

Complex numbers and inequalities

The set of complex numbers with its operations of addition and multiplication is a field, but it is impossible to define any relation ≤ so that becomes an ordered field. To make an ordered field, it would have to satisfy the following two properties:

- if a ≤ b, then a + c ≤ b + c;

- if 0 ≤ a and 0 ≤ b, then 0 ≤ ab.

Because ≤ is a total order, for any number a, either 0 ≤ a or a ≤ 0 (in which case the first property above implies that 0 ≤ −a). In either case 0 ≤ a; this means that i > 0 and 1 > 0; so −1 > 0 and 1 > 0, which means (−1 + 1) > 0; contradiction.

However, an operation ≤ can be defined so as to satisfy only the first property (namely, "if a ≤ b, then a + c ≤ b + c"). Sometimes the lexicographical order definition is used:

- a ≤ b, if

- Re(a) < Re(b), or

- Re(a) = Re(b) and Im(a) ≤ Im(b)

It can easily be proven that for this definition a ≤ b implies a + c ≤ b + c.

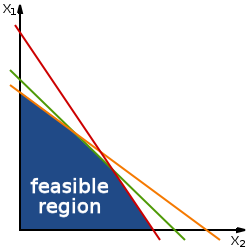

Systems of inequalities

Systems of linear inequalities can be simplified by Fourier–Motzkin elimination.

The cylindrical algebraic decomposition is an algorithm that allows testing whether a system of polynomial equations and inequalities has solutions, and, if solutions exist, describing them. The complexity of this algorithm is doubly exponential in the number of variables. It is an active research domain to design algorithms that are more efficient in specific cases.

See also

- Binary relation

- Bracket (mathematics), for the use of similar ‹ and › signs as brackets

- Inclusion (set theory)

- Inequation

- Interval (mathematics)

- List of inequalities

- List of triangle inequalities

- Partially ordered set

- Relational operators, used in programming languages to denote inequality

References

- ^ "Inequality Definition (Illustrated Mathematics Dictionary)". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Halmaghi, Elena; Liljedahl, Peter. "Inequalities in the History of Mathematics: From Peculiarities to a Hard Discipline". Proceedings of the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Mathematics Education Study Group.

- "Earliest Uses of Symbols of Relation". MacTutor. University of St Andrews, Scotland.

- ^ "Inequality". www.learnalberta.ca. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Polyanin, A.D.; Manzhirov, A.V. (2006). Handbook of Mathematics for Engineers and Scientists. CRC Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4200-1051-0. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Much Less". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Much Greater". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Drachman, Bryon C.; Cloud, Michael J. (2006). Inequalities: With Applications to Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-3872-2626-5.

- "ProvingInequalities". www.cs.yale.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Simovici, Dan A. & Djeraba, Chabane (2008). "Partially Ordered Sets". Mathematical Tools for Data Mining: Set Theory, Partial Orders, Combinatorics. Springer. ISBN 9781848002012.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Partially Ordered Set". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Feldman, Joel (2014). "Fields" (PDF). math.ubc.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Stewart, Ian (2007). Why Beauty Is Truth: The History of Symmetry. Hachette UK. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-4650-0875-9.

- Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie (Apr 1988). The C Programming Language. Prentice Hall Software Series (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs/NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131103628. Here: Sect.A.7.9 Relational Operators, p.167: Quote: "a<b<c is parsed as (a<b)<c"

- Laub, M.; Ilani, Ishai (1990). "E3116". The American Mathematical Monthly. 97 (1): 65–67. doi:10.2307/2324012. JSTOR 2324012.

- Manyama, S. (2010). "Solution of One Conjecture on Inequalities with Power-Exponential Functions" (PDF). Australian Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications. 7 (2): 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Gärtner, Bernd; Matoušek, Jiří (2006). Understanding and Using Linear Programming. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-30697-8.

Sources

- Hardy, G., Littlewood J. E., Pólya, G. (1999). Inequalities. Cambridge Mathematical Library, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05206-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Beckenbach, E. F., Bellman, R. (1975). An Introduction to Inequalities. Random House Inc. ISBN 0-394-01559-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Drachman, Byron C., Cloud, Michael J. (1998). Inequalities: With Applications to Engineering. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98404-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grinshpan, A. Z. (2005), "General inequalities, consequences, and applications", Advances in Applied Mathematics, 34 (1): 71–100, doi:10.1016/j.aam.2004.05.001

- Murray S. Klamkin. "'Quickie' inequalities" (PDF). Math Strategies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Arthur Lohwater (1982). "Introduction to Inequalities". Online e-book in PDF format.

- Harold Shapiro (2005). "Mathematical Problem Solving". The Old Problem Seminar. Kungliga Tekniska högskolan.

- "3rd USAMO". Archived from the original on 2008-02-03.

- Pachpatte, B. G. (2005). Mathematical Inequalities. North-Holland Mathematical Library. Vol. 67 (first ed.). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-51795-2. ISSN 0924-6509. MR 2147066. Zbl 1091.26008.

- Ehrgott, Matthias (2005). Multicriteria Optimization. Springer-Berlin. ISBN 3-540-21398-8.

- Steele, J. Michael (2004). The Cauchy-Schwarz Master Class: An Introduction to the Art of Mathematical Inequalities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54677-5.

External links

- "Inequality", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Graph of Inequalities by Ed Pegg, Jr.

- AoPS Wiki entry about Inequalities

the symbol for "greater than" bisected by a slash, "not". The same is true for not less than,

the symbol for "greater than" bisected by a slash, "not". The same is true for not less than,

and

and  are

are  an

an

where

where  is the

is the

In the limit of p → 0, the upper and lower bounds converge to ln(x).

In the limit of p → 0, the upper and lower bounds converge to ln(x).

with its operations of

with its operations of