The Tale of the Moon Cuckoo (Mongolian: Saran kökögen-ü namtar) is a traditional Mongolian opera by the composer, writer, and incarnate lama Dulduityn Danzanravjaa, composed between 1831 and 1832 and first performed in 1833. It tells the story of a prince who is tricked into being a cuckoo by a manipulative companion, who then impersonates the prince and causes the decline of their kingdom.

A significant work of Mongolian theatre, the Tale of the Moon Cuckoo is unrelated to Western opera and was significantly influenced by the Tibetan tradition of lhamo. Danzanravjaa based the opera's story on a 1737 Tibetan work of the same name, and combined Tibetan elements with Chinese costuming and Buddhist philosophical concepts. Performed by at least eighty-seven actors in a specially designed theatre, the Tale of the Moon Cuckoo lasted for a month and was interspersed with unrelated comedic or educational pieces. It was performed for many years after Danzanravjaa's death in 1856 until the Communist purges in the 1930s.

Synopsis

A prince lives happily in his father's kingdom, beloved by all and engaged to a beautiful woman. A jealous advisor of the king manipulates the prince into replacing his friends with the advisor's son. Together, the prince and his new companion become experts at transferring their souls into other bodies.

One day, when the two are meditating in the forest, they decide to transfer their souls into cuckoos. The companion seizes his moment, and he places his soul in the prince's body before throwing his own body into the river. Returning to the kingdom, the companion poses as the prince. Distraught by their son's apparent death, the advisor and his wife kill themselves, but their son does not care—he replaces the prince's fiancée with her jealous friend and acts so dubiously that the queen dies and the king loses heart. The kingdom begins to decline.

The fiancée resolves to figure out what is amiss. After months of wandering, she meets a travelling monk with a cuckoo companion; the monk tells her that the cuckoo was a prince who had been betrayed and who was now teaching the animals Buddhism in the hope that he could one day become human again. Although the fiancée tells the king what has happened and the impostor is discovered, the prince is unable to return to his human body. Since that day, the cuckoo's song, calling for a change in fate, has indicated the coming of spring.

Description

Dulduityn Danzanravjaa was born in 1803 into an extremely poor family. After being accepted at the age of seven into a Buddhist monastery, he quickly displayed poetic and religious talent. Danzanravjaa was soon acclaimed not only as a lama but as the fifth incarnation of Noyon Khutagt. He studied the poems of Kelden Gyatso and philosophical debate before beginning a life of secluded wandering, drinking, and the occasional building of hermitages in 1822. Having become a disciple of the third Jangjiya Khutugtu (another lineage of incarnate lamas), Danzanravjaa was alternately excluded from and included in Inner Mongolian society. He died in 1856. Danzanravjaa's most famous works, aside from the Tale of the Moon Cuckoo, include Ulemjiin Chanar (lit. Extraordinary Qualities), Galuu khün khoyor (lit. The Goose and the Man), Öwgön shuwuu (lit. The Old Man and the Bird), and Ichige, ichige (lit. For Shame, for Shame). His works heavily mocked organised religion and displayed Danzanravjaa's own eccentric spiritual orientation.

Danzanravjaa conceived the concept of the Tale of the Moon Cuckoo when staying in 1831 in Alashan, at the temple of Baruun Khiid, which had a tradition of performing Tibetan-style opera. His composition was based on a 1737 work of Tibetan religious literature, also entitled Tale of the Moon-Cuckoo, which had first been translated into Mongolian in 1770. Performances began in 1833 after he had hired actors from Alashan and built a wooden theatre in Mongolia. A complete performance of the opera lasted for a month; each day's performance would begin in mid-morning and end in mid-to-late afternoon, and was interspersed with unrelated comedic and artistic pieces. The shorter version of the opera lasted fifteen days. Danzanravjaa wrote the libretto, which was subject to constant revision. He also designed the colourful costumes and trained the cast, which numbered at least eighty-seven.

The Tale of the Moon Cuckoo combined Tibetan influences—most prominent in the opera's tsam dancing—with Qing Chinese cultural elements, such as the makeup the opera used in place of the Tibetan tsam masks. The opera emphasised numerous concepts of Buddhist philosophy, most notably transcendence through meditation, the principle of karma, and the significance of respect for nature.

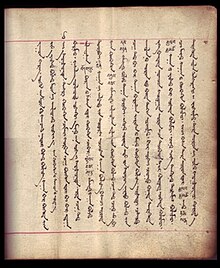

Despite being temporarily banned after Danzanravjaa's death, the opera was very popular and was performed very often until the 1930s, when the Mongolian People's Republic carried out a series of repressive purges in which Danzanravjaa's monastery was destroyed. Many of his documents were hidden in mountain caves by the monastery's curator and survived the purges—the curator's grandson exhumed the artefacts following the 1990 revolution. They are today housed in the Danzanravjaa Museum in Sainshand.

References

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 130.

- Atwood 2004, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 131; Humphrey 2005.

- Atwood 2004, p. 131; Sardar 2016.

- Atwood 2004, p. 336.

- Atwood 2004, p. 131; Sardar 2016; Ariunaa 2021.

- ^ Ariunaa 2021.

- Atwood 2004, p. 131; Elverskog 2013, p. 14.

- May 2008, p. 86; Sardar 2016.

Sources

- Ariunaa, Jarghalsaikhan (20 January 2021). "Noyon Khutagt Danzanravjaa's Theater". UB Post. Ulaanbaatar. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Elverskog, Johan (2013). "China and the New Cosmopolitanism" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (233). University of Pennsylvania Press. ISSN 2157-9687.

- Humphrey, Caroline (2005). "The Treasures of Danzan Ravjaa (EAP031)". Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- May, Timothy (2008). Culture and Customs of Mongolia. Culture and Customs of Asia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-3133-3983-7.

- Sardar, Hamid (2016). "Noyon Khutuktu Danzan Ravjaa". The Treasury of Lives. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2023.