Site Overwiev Site Overwiev | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Region | Valpolicella |

| Coordinates | 45°33′44.27″N 10°54′36.69″E / 45.5622972°N 10.9101917°E / 45.5622972; 10.9101917 |

| Type | Temple |

| History | |

| Abandoned | Low Roman Age |

| Periods | 6th century BC - 1st century BC |

| Cultures | Protostoric- Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1835 |

| Excavation dates | 1835, 2010, 2013 |

| Management | Superintendence of archaeology, fine arts and lanscape for the provinces of Verona, Rovigo and Vicenza |

| Public access | yes |

| Website | www |

45°33′44.27″N 10°54′36.69″E / 45.5622972°N 10.9101917°E / 45.5622972; 10.9101917 The temple of Minerva is an archaeological area located on Mount Castelon, in the municipality of Marano di Valpolicella, in the province of Verona. The site, popular as a sanctuary at least since the 6th century BC, became a place of worship dedicated to Minerva in the 2nd century BC.

History

The site is located on the eastern slopes of Mount Castelòn, between the valleys of Fumane and Marano. In this place, in ancient times, there must have been a source of water that sprung from the rock, and a natural depression where water probably accumulated. This site was visited since the Iron Age, in the 6th century BC: the ancient believers, in addition to allocating the natural cavity to the collection of offerings or sacrificial remains, they set up a space to light a votive fire, that is, a place where to burn gifts for the gods. The archaeological investigations (made by the accumulation of burned earth, which is all that remains of this phase of the site) have returned various organic remains (seeds, wood fragments and remains of food) as well as bronze rings, fibulae, bullae and ceramic pieces.

Since the end of the 2nd century BC the site, which must have acquired a certain importance and cultural value, was home to a stone-made temple dedicated to Minerva. The building technique and architectural style suggest that a Roman-Hellenistic client paid for this intervention. Little is known about this building (which largely lies under the ruins of the most recent temple): it was equipped with a central room paved in pink opus caementicium, with inserted mosaic tiles. To the south of the temple there was an elongated environment, paved in white opus caementicium; to the north another space with pink limestone slabs floor. The temple had to be richly frescoed, since numerous pictorial fragments have been recovered: the decoration was in the so-called "first Pompeian style", which simulated the stone and marble walls of Hellenistic palaces, and, in this case, had a wave pattern along the entire lower part of the walls, perhaps in reference to the water present at the site.

In the Augustan age or in the first decades of the Imperial age the temple was completely rebuilt; the new structure, which is the one that still shows visible remains, had at its center an internal quadrangular inner chamber, about 8-9 meters high, with a small ritual basin in the northwest corner. Around it ran three galleries at the same height of the inner chamber, according to an architectural plan inspired by the Celtic or Germanic area temples: these were located on the north, east and south sides of the inner chamber, they were open and had a Doric colonnade (part of the northern side was closed by a wall covered by a reticulated vestment); the fourth side, to the west towards the mountain, was instead occupied by a channel of the same size of the galleries.

The site fell progressively into decline in the Low Roman age, also due to the spread of christianity. The roof was destroyed during a fire and the temple, no longer repaired, fell into ruins and ended up being buried by the sediment and subsidence of the rock on the side of the mountain. Centuries later, the nearby church of Santa Maria di Valverde was built (formerly called "di Santa Maria Minerbe" or "di Santa Maria sopra Minerva").

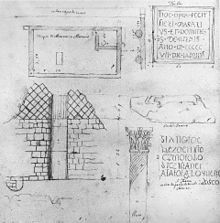

The rediscovery of the temple began thanks to Girolamo Orti Manara, who, after a series of researches in 1835, began a campaign of excavations on the site (the presence of a temple on the mountain was already known by the inhabitants and local historians, although the precise place had been forgotten). Despite the technical difficulties he managed to find part of the remains of the last building in addition to various finds and inscriptions, which were drawn on paper by Giuseppe Razzetti.

Despite this discovery, the place was again abandoned. A development project began in 2005, after the terracing ("marogne") construction in the years between the two wars, destined for agricultural use. Once the remains already found by Orti Manara were uncovered, a second series of excavations was carried out that brought the other parts of the imperial temple back to life and allowed the traces of the oldest sites to be documented. The archaeological area was opened to the public in 2020.

References

- ^ "Il Tempio di Minerva". tempiodiminerva.it. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Bruno & Falezza, p. 45-46. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrunoFalezza (help)

Bibliography

- Brunella, Bruno; Falezza, Giovanna (2016). Archeologia e storia sul Monte Castelon di Marano di Valpolicella. Mantova: SAP - Società Archeologica. ISBN 978-88-99547-01-1.

- Bruno, B.; Falezza, G.; Donisi, M.; Manfrin, P. (2022). Marano di Valpolicella. Intervento di valorizzazione nel sito archeologico del Tempio di Minerva sul Monte Castelon. Vol. Archeologia del Veneto, Notiziario delle Soprintendenze. Mantova. pp. 179–183.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Official site on tempiodiminerva.it