"The Day of Doom: or, A Poetical Description of the Great and Last Judgment" is a religious poem by clergyman Michael Wigglesworth that became a best-selling classic in Puritan New England for a century after it was published in 1662 by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson. The poem describes the Day of Judgment, on which a vengeful God judges and sentences all men, going into detail as to the various categories of people who think themselves excusable who will nonetheless end up in Hell.

Popularity

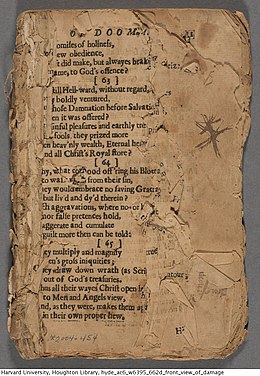

It "attained immediately a phenomenal popularity. The entire first printing of eighteen hundred copies was sold within a year, and for the next century The Day of Doom held a secure place in New England Puritan households". According to the Norton Anthology of American Literature (Volume 1), "about one out of every twenty persons in New England bought it". The poem was so popular that the early editions were thumbed to shreds. Only one fragmentary copy of the first edition is known to exist, and second editions are exceptionally rare. Sales of The Day of Doom soon exceeded Wigglesworth's pastoral salary (which had been significantly cut while he was unable to fulfill pastoral duties – he worked a side-job as a physician to provide sufficient income for his large household). Its repeated republication made it, according to one 20th century scholar, “the most popular poem that New England has ever known”, with circulation “beyond the wildest dreams of the most high pressure publisher of modern fiction”.

At the funeral of Michael Wigglesworth, Cotton Mather preached, describing the circumstances of the book for which the deceased was best known: “And that he might yet more Faithfully set himself to do Good, when he could not Preach, he Wrote several Composures, wherein he proposed the Edification of such Readers, as are for plain Truths dressed up in a Plain Meter. These composures have had their Acceptance and Advantage ... and one of them the Day of Doom, which has been often reprinted in both Englands, may perhaps find our Children, till the day itself arrive.”

This seemed plausible at the time and for the century and a half to come, though interest notably flagged in the following hundred-fifty years.

Later Assessment

This early popularity did not prevent early 20th century scholars of literature and scholars of the colonial period more broadly from strongly criticizing The Day of Doom as dull, uncreative, and depressing. The assessment of Vernon Parrington in The Colonial Mind is typical: “It is not pleasant to linger in the drab later years of century. A world that accepted Michael Wigglesworth for its poet, and accounted Cotton Mather its most distinguished man of letters, had certainly backslidden in the ways of culture.” The poem is a "doggerel epitome of Calvinistic theology", according to the anthology, Colonial Prose and Poetry (1903).

Contents

See Reference 1 for the text of the poem.

Over its two hundred and twenty-four stanzas (the longest of any poem in the Colonial Period), The Day of Doom is an argument to encourage the faithful and challenge the faithless through describing plainly how scripture depicts the amazement (and later the judgment per se) of the unwise. This is a form of, while not quite apologetics, evangelistic messaging. There are similarities and contrasts to other “hellfire and brimstone” preaching and writing; the poem does not fit into the typical paradigm.

Later editions included scripture references in the margins making the connections clear: each verse of the poem was inspired by a particular scripture passage. Wigglesworth stayed limited to scripture itself. In verse XVI, he wrote “And therefore I must pass it by, lest speaking should transgress.” This describes immediately his reluctance to describe God's glory, but it is also true in a broader sense. He does not speak without clear and complete warrant from scripture.

References

- ^ Wigglesworth, Michael (1867) . The day of doom: or, A poetical description of the great and last judgment. American News Company – via Internet Archive.

- Catalog entry for Harvard Library's 1st edition copy.

- Hill-Zeigler, Patricia J. (January 1998). "In the Name of the Father". Doctoral Dissertations. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Murdoch, Kenneth B. (1929). The Day of Doom. New York: The Spiral Press. pp. x.

- Matthiessen, F. O. (October 1928). "Michael Wigglesworth, a Puritan Artist". The New England Quarterly. 1 (4): 492. doi:10.2307/359529. JSTOR 359529.

- Parrington, Vernon L. (1927). The Colonial Mind: 1620–1800. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & Co. p. 85.

- Trent, William P. and Wells, Benjamin W., Colonial Prose and Poetry: The Beginnings of Americanism 1650–1710, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1903 single-volume edition.

External links

- Online text version, with Scripture references (University of Virginia)

- The Day of Doom archive.org

- "Michael Wigglesworth," short bio by Danielle Hinrichs

This article related to a poem is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |