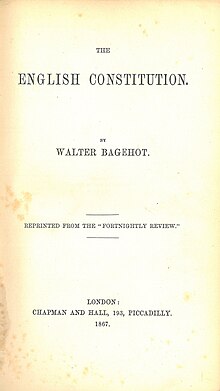

Title page of the first edition Title page of the first edition | |

| Author | Walter Bagehot (3 February 1826 – 24 March 1877) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Chapman & Hall |

| Publication date | 1867 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 348 |

| OCLC | 60724184 |

The English Constitution is a book by Walter Bagehot. First serialised in The Fortnightly Review between 15 May 1865 and 1 January 1867, and later published in book form in 1867, it explores the constitution of the United Kingdom—specifically the functioning of Parliament and the British monarchy—and the contrasts between British and American government. The book became a standard work which was translated into several languages.

While Walter Bagehot's references to the Parliament of the United Kingdom have become dated, his observations on the monarchy are seen as central to the understanding of the principles of constitutional monarchy.

Summary

| This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (January 2015) |

Bagehot began his book by saying, in effect: do not be fooled by constitutional theories (the ‘paper description’) and formal institutional continuities (‘connected outward sameness’) – concentrate instead on the real centres of power and the practical working of the political system (‘living reality’). He dismissed the two theories of the division of powers (between legislature, executive and judiciary) and of ‘checks and balances’ (between the monarchical, aristocratic and democratic elements of the constitution) as ‘erroneous’. What was crucial, he insisted, was to understand the difference between the ‘dignified parts’ of the constitution and the ‘efficient parts’ (admitting that they were not ‘separable with microscopic accuracy’). The former ‘excite and preserve the reverence of the population’, the latter are ‘those by which it, in fact, works and rules’.

England had a ‘double set’ of institutions – the dignified ones ‘impress the many’ while the efficient ones ‘govern the many’. The dignified or ‘theatrical’ parts of the system played the essential role of winning and sustaining the loyalty and confidence of the mass of ordinary people whose political capacities were minimal or non-existent; they helped the state to gain authority and legitimacy, which the efficient institutions could then use. Bagehot was an unashamed elitist who believed bleakly that the ‘lower orders’ and the ‘middle orders’ were ‘narrow-minded, unintelligent, incurious’. Throughout The English Constitution, there are references to ‘the coarse, dull, contracted multitude’, ‘the poor and stupid’, ‘the vacant many’, ‘the clownish mass’.

The dignified parts of the constitution were complicated, imposing, old and venerable; but the efficient parts were simple and modern. The ‘efficient secret’ at the heart of it all was ‘the close union’ and ‘nearly complete fusion’ of executive and legislative powers in the Cabinet - the ‘board of control’ which rules the nation. ‘The use of the Queen, in a dignified capacity, is incalculable’, opened the chapters of the book dealing with the monarchy. It acted as a ‘disguise’ and strengthened the government through its combination of mystique and pageantry. He famously summed up the monarch's role as involving ‘the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn’.

The House of Lords also had a dignified role. It had become a delaying and revising chamber – it was not a bulwark against revolution but must ultimately ‘yield to the people’ (i.e. the House of Commons). ‘The cure for admiring the House of Lords was to go and look at it’, he quipped. The danger it faced was not abolition but decline, and Bagehot supported the creation of life peers to reform it. Bagehot counted the House of Commons as one of the efficient institutions running the country: ‘the whole life of English politics is the action and reaction between the ministry and the Parliament’. The Commons was ‘the ruling and choosing House’ – its main function was ‘elective’, it was ‘the assembly which chooses our president’. It had other roles too: to express the mind of the people; to teach the nation; to communicate grievances; to legislate. Political parties, he recognised, were ‘inherent in it . . . bone of its bone, and breath of its breath’, but he saw party politics in loose and moderate and Westminster-centric terms.

He feared and opposed dogmatic and programmatic ‘constituency government’ and outside party organisations controlling MPs and making them into ‘immoderate representatives for every “ism” in all England’. He would have no truck with what he called ‘ultra-democratic theory’ – one person, one vote. ‘Once you permit the ignorant class to begin to rule you may bid farewell to deference for ever’, he argued – and deference was the key social prop of the system. The mass of people deferred to the pomp and splendour of the ‘theatrical show of society’, but also the numerical majority delegated to an educated and competent minority the power of choosing its rulers. The middle classes were, in this regime, ‘the despotic power in England’ and could be expected to choose a good legislature which in turn would select a competent government.

Bagehot was willing to accept some limited parliamentary reform to give more weight to northern industrial areas and even permit some working-class representatives. But he was shocked and dismayed by the Second Reform Act's dramatic extension of the franchise in 1867, which virtually doubled the size of the electorate. In the Introduction to the second edition of The English Constitution in 1872, he was gloomy about a political future in which ‘both our political parties will bid for the support of the working man . . . both of them will promise to do as he likes if he will only tell them what it is’. ‘I am exceedingly afraid’, he admitted, ‘of the ignorant multitude of the new constituencies’.

Legacy

A column in the magazine The Economist, concerning British affairs, is named after Bagehot. Bagehot also influenced Woodrow Wilson, who wrote Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics in 1885, inspired by The English Constitution. Joaquim Nabuco was also inspired by The English Constitution, dedicating a whole chapter about the book in his memoirs.

Generations of British monarchs and their heirs apparent and presumptive have studied Bagehot's analysis. In season 1 of television series The Crown, young Princess Elizabeth's tutor quotes Bagehot to her, which she later recalls when she becomes Queen Elizabeth II.

References

- ^ Walter Bagehot (1867). The English Constitution (1st ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 60724184.

- See also Bagehot, Walter (1888). The English Constitution (Fifth ed.). London: Kegan, Paul, Trench & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- "Where do The Economist's unusual names come from?". The Economist. 5 September 2013. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Woodrow Wilson (1885). Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co. OCLC 504641398.

- Vernon Bogdanor (1997). The Monarchy and the Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-827769-9.

Sources

- Bagehot, Walter (1867). The English Constitution (1st ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 60724184.

- Bagehot, Walter (1872). The English Constitution (New (2nd) ed.). London: H. S. King. OCLC 60724443.

- McMaster University version.

- Project Gutenberg version (EBook #4351, posted on 11 August 2009).

The English Constitution public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The English Constitution public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Briggs, Asa, “Trollope, Bagehot, and the English Constitution,” in Briggs, Victorian People (1955) pp. 87–115. online

Categories: