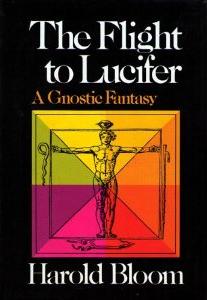

Cover of the first edition, showing jacket illustration of the Primal Man from De Occulta Philosophia by Cornelius Agrippa Cover of the first edition, showing jacket illustration of the Primal Man from De Occulta Philosophia by Cornelius Agrippa | |

| Author | Harold Bloom |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Muriel Nasser |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus and Giroux |

| Publication date | 1979 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 240 |

| ISBN | 0-374-156441 |

The Flight to Lucifer: A Gnostic Fantasy is a 1979 fantasy novel by American critic Harold Bloom, inspired by his reading of David Lindsay's fantasy novel A Voyage to Arcturus (1920). The plot, which adapts Lindsay's characters and narrative and features themes drawn from Gnosticism, concerns Thomas Perscors, who is transported from Earth to the planet Lucifer by Seth Valentinus.

The book received negative responses, and was compared, including by Bloom himself, to the film Star Wars (1977). Bloom eventually repudiated the work.

Plot summary

Thomas Perscors ("through fire"), an incarnation of Primal Man, is taken from Earth to the planet Lucifer by Seth Valentinus, a reincarnation of the gnostic theologian Valentinus. Their guide is Olam, who is an Aeon, an emanation of the true god. Lucifer is controlled by "Saklas", which is a Gnostic name for the false creator. Olam has brought Perscors to Lucifer to fight Saklas, and has brought Valentinus so he can remember his true self. Perscors cripples Saklas and changes the order of things across all of Lucifer.

Publication history

The Flight to Lucifer was first published in the United States and Canada by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1979.

Reception

The Flight to Lucifer received a positive review from Frank McConnell in The New Republic, mixed reviews from Martin Bickman in Library Journal and the critic John Leonard in The New York Times, and negative reviews from Marilyn Butler in the London Review of Books and from Kirkus Reviews. The book was also discussed by the journalist David Kipen in The Atlantic.

McConnell described the novel as "rich and brilliant", and wrote that it dealt, in fictional form, with the themes of Bloom's non-fiction literary criticism. He considered it "difficult reading", and different in character from the work of fantasy writers such as C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, in that it avoided "the comforting details of everyday reality". He credited Bloom with coming close to recreating "the original Gnostic sensibility". Bickman wrote that, "Despite the often dazzling imagery and the fast narrative pace, a reader without a detailed knowledge of Gnosticism is likely to be disappointed, if not dismayed", but concluded that the novel belongs, "in large public and academic collections as another facet of one of our most important and controversial literary theorists." Leonard compared the novel to the science fiction writer Frank Herbert's Children of Dune (1976) and to Star Wars (1977), and questioned the accuracy of Bloom's treatment of Gnosticism. Butler compared the novel to Lewis's Perelandra (1943), and suggested that it showed that Bloom was "author of a single complex personal myth", writing that he had used fantasy as "a vehicle for an alternative interpretation of reality". However, while she believed that its discussion of religion would appeal to some readers, the novel had "practically nothing to recommend it" as fiction. She criticized its plot as lacking "suspense, pace and variety." Kirkus Reviews described the novel as tedious and, "A close-to-unreadable exercise, only for those who share Bloom's gnostic preoccupations--or collectors of literary oddities."

Kipen dismissed the novel as unsuccessful.

Bloom described The Flight to Lucifer as his "first attempt at literary fantasy". He explained that the novel was inspired by David Lindsay's A Voyage to Arcturus (1920), with his characters "Thomas Perscors" and "Saklas" being the equivalents, respectively, of Lindsay's original characters "Maskull" and "Crystalman". He identified Edmund Spenser and Franz Kafka as additional influences on his novel. He gave his relationship to A Voyage to Arcturus, which according to his own account he had "obsessively" read hundreds of times, as an example of his theory of the anxiety of influence. He considered it superior to his novel, partly because he attempted deliberately to assimilate Lindsay's characters and narrative to second-century Gnosticism rather than being a "naive Gnostic" like Lindsay, who according to Bloom inadvertently created a personal Gnostic heresy. He wrote that despite its "violent narrative", his novel "has too much trouble getting off the ground" and "reads as though Walter Pater was writing Star Wars." He nevertheless saw The Flight to Lucifer as having some merit, and wrote that it "does get better as it goes along" and "towards its close can be called something of a truly weird work".

Bloom stated in a 2015 interview with Daniel D'Addario in Time that after re-reading The Flight to Lucifer, he decided that the novel would "never do", and that, "I had to pay the publisher not to have a second printing of the paperback. If I could go around and get rid of all the surviving copies, I would."

References

- Bloom 1979, pp. 3–240.

- Bloom 1979, p. iv.

- ^ McConnell 1979, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Bickman 1979, p. 848.

- ^ Leonard 1979.

- ^ Butler 1982, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews 1979.

- ^ Kipen 2005, p. 177.

- Bloom 1983, pp. 206–207, 213, 222–223.

- D'Addario 2015, p. 64.

Sources

Books

- Bloom, Harold (1983). Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503354-X.

- Bloom, Harold (1979). The Flight to Lucifer. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-15644-1.

Journals

- Bickman, Martin (1979). "The Flight to Lucifer (Book Review)". Library Journal. 104 (7). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Butler, Marilyn (1982). "Bloom's Gnovel". London Review of Books. 2 (13).

- D'Addario, Daniel (11 May 2015). "10 Questions with Harold Bloom". Time. Vol. 185, no. 17.

- Kipen, David (2005). "Easier said than done". The Atlantic. 295 (1). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Leonard, John (1979). "Books of the Times". The New York Times (April 30, 1979).

- McConnell, Frank (1979). "The Flight to Lucifer: A Gnostic Fantasy". The New Republic. Vol. 180, no. 20.

- "Kirkus Review". Kirkus Reviews (May 1, 1979). 1979.