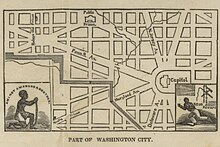

The Yellow House was the slave jail of the Williams brothers (Thomas Williams and William H. Williams), located at 7th Street and Maryland Avenue in Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. In 1838, William H. Williams directed people wishing to buy or sell slaves to his jail "on 7th street the first house south of the market bridge on the west side".

The Williams' slave-trading business was apparently "large and well-known to traders in Richmond and New Orleans." The three-story building was made of brick covered in yellow-painted plaster and served as a navigation landmark for visitors to the city: "In an era before the memorials to Washington or Jefferson (much less the yet-unknown Lincoln) had been erected, D.C. travelers oriented themselves based on the Yellow House, which stood as a prominent landmark within the nation's capital."

In 1843 a column in The Liberator referenced it: "If ever you have been to Washington you have probably noticed a large yellow house which stands about a mile from the avenue near the Potomac—That is the slave prison. It is owned by a celebrated slave trader, who has made a large fortune by following his hellish traffic. Slaves are not sold openly at public auction in this district so frequent as formerly. The traffic is carried on in secret. Thus public opinion begins to be felt even in the slave regions."

There are at least two contemporary descriptions of the jail. One is from an account of attempting to rescue a man who had been kidnapped into slavery in 1848:

Your old friend, Mr. ---- and myself started for the slave pen. The evening was not precisely cloudy, but the moon shone dimly through a smoky atmosphere. You know the building. It stands removed some distance from either road. As we approached, I could not but reflect that within its gloomy walls were yet retained all the horrid barbarity of the darker ages: yea, worse than this...Soon after we entered the yard, we met two men who appeared to be on patrole duty.— One of them turned round, and walked back to us, inquired if we wished to see Mr. Williams. We told him we did. He said Mr. Williams was not in, but his agent was. We told him we would then see the agent. As we came near the door, he told us to keep round to the left of him, as a large dog was chained in front of the door. Ascending the steps, he led us through a dark passage to a somewhat spacious room, having the appearance of an office. In front of a fire two men were sitting smoking cigars. He introduced us to one of them as the agent. To him we made known our errand. They both rose to their feet, and the agent said 'The negur has gone. We took him immediately on board ship at Alexandria, and he has sailed for New Orleans.' We told him the circumstances of his right to freedom. He assured us that it was not so—that 'the negur' told him he has not paid a cent.

The building was deserted and derelict in 1853 when a news writer from Syracuse reported "I noticed that Williamson's [sic] slave pen had been dismantled, proparatory either to a removal or reconstruction of the building, it is situated in a lonely, though pleasant spot. An air of sorrow pervades it as though the groans, the sighs, and blood of its victims were still rising from its cells, and weighing down the atmosphere with their burden of grief."

The Yellow House was located across from where the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden stands today. The private prison was in use as a waystation of the interstate slave trade from 1836 to 1850. During his one term in the U.S. Congress, Abraham Lincoln recorded that he could see the building from the U.S. Capitol. A few years earlier, Solomon Northrup, a victim of kidnapping into slavery, could see the Capitol from his cell in the Williams' dungeon.

See also

References

- ^ Forret, Jeff (2020). "Chapter 2: The Yellow House". Williams' Gang: A Notorious Slave Trader and his Cargo of Black Convicts. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–54. doi:10.1017/9781108651912.003. ISBN 978-1-108-65191-2.

- "Dear Sir: There is here in Washington a Slave jail, or "Negro Pen"..." Portland Press Herald. 1844-10-31. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- "William H. Williams – Yellow House". Daily National Intelligencer and Washington Express. 1838-09-27. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- Corrigan, Mary Beth (2001). "Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C." Washington History. 13 (2): 4–27. ISSN 1042-9719.

- "Northern Subserviency – Slavery in the District". The Liberator. 1843-03-31. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ "From the True Democrat - Washington Correspondence - Washington City". Anti-Slavery Bugle. 1848-02-04. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- "A Deserted Slave Pen in Washington". Anti-Slavery Bugle. 1853-06-18. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-06-02.

- Forret, Jeff (July 22, 2020). "The Notorious 'Yellow House' That Made Washington, D.C. a Slavery Capital". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Deutsch, James (2020). "D.C.'s Slave Trade Ended Here, Next Door to the Smithsonian". Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 2023-12-10.

Categories: